The Grand Hall of Platitudes, where originality goes to die (In actuality, the Osgoode Hall Library in Toronto via Flickr)

Any effective phrase can get burnt out on parody or overuse, but some tropes are so obvious that to use them at all is like announcing the arrival of a washed-up celebrity. Let's probe the origins of some of the most famous (and perhaps best avoided) cliches lurking in our literary past:

(via Dieselpunks)

“Little Did They Know”

The phrase “little did she/he/they know” has plenty of history. The question is, when did it start being used for cheap suspense? The inversion of subject and verb sounds stilted and melodramatic, so the obvious culprit would be 19th century fiction. But perhaps not everything is as it seems.

The phrase does appear in 19th century pieces, such as Ann Marsh-Caldwell's Love and Duty: A Novel, but as only dramatic irony to refer to something we're aware of but the protagonist isn't, such as, “Little did he know what was passing in that young heart.” Occasionally the phrase appears in first person when a character is gloating or hiding something, such as in Arthur Conan Doyle's The Brigadier Gerard: “Little did they know I was on top of that very mound.” It is categorically not used for suspense, even in novels such as East Lynne by Ellen Wood, where cheap hooks and bad prose abound. Likewise, “unbeknownst” isn't widely used in this way until the 20th century (despite being coined in Victorian times), and neither are equivalent phrases such as “little did he/she suspect.” It seems that for once, prose writing in the 19th century can throw off its collective top hat and cheer for a verdict of not guilty.

So when did the “little did they know” explosion take place? The epicentre appears to be American magazines of the 1930s to 1950s, especially those aimed at adventurously inclined men and boys. Flying Magazine, May 1931: “Little did he know that before he again placed his feet on Mother Earth he would have set a record.” The Rotarian, December 1931: “Little did he know that he was then on the verge of discovering a hidden treasure.” Boy's Life, November 1939: “Little did he know that the worst was yet to be.” Motorboating magazine is the most shameless offender and uses “Little did they know” as a complete sentence in a 1942 article. The cliche crept into Life magazine in the ‘50s and from there became a major U.S. export.

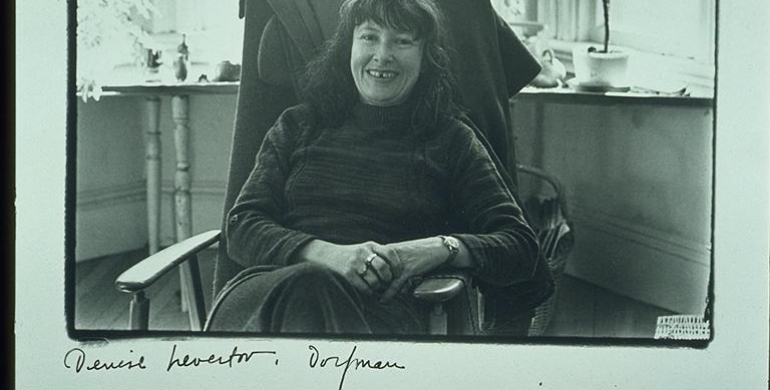

(via Smith College Libraries)

“It was a Dark and Stormy Night”

“It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents — except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.” This is the opening to Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 novelistic yawn-fest Paul Clifford. It has become the archetypical example of the excesses of purple prose — so much so that in 1982 San Jose State University Professor Scott E. Rice created the annual Bulwer-Lytton contest to see who could “compose the opening sentence to the worst of all possible novels.”

Yet Bulwer-Lytton's work was met with praise and success in his time. He reputedly convinced Charles Dickens to change his vision of Great Expectations from an unhappy ending to something more crowd pleasing and coined the phrases “the mighty dollar” and “the pen is mightier than the sword.”

“Aesop and Priests” by Francis Barlow (via Wikipedia)

“Once Upon a Time”

It is hardly surprising that “once upon a time” has murky origins. The Oxford English Dictionary is sometimes cited as placing the inception around 1380 with The Canterbury Tales, but a quick glance will show that people don't begin tales with “once upon a time” in Chaucer's work.

A hint exists in the 1595 play The Old Wives Tale by George Peel, where the character Madge begins a tale with: “Once upon a time there was a king, or lord, or duke.” The play is a deliberate parody of romantic drama, and Madge's aimless, wandering narratives are included to satirise a (presumably familiar) form of oral history, which suggests that “Once upon a time” was a well-known trope of storytelling in the 1500s.

A more concrete example of the phrase in its modern form comes in the 1694 work Fables of Aesop and Other Eminent Mythologists: With Morals and Reflexions by Sir Roger L'Estrange. The tale of “The Hares and the Frogs” opens with “Once upon a time” and, perhaps more importantly, shows the trope being used to commence a short story for children. A pamphlet from around the same time begins a digression “Once upon a time (to use the old English style),” suggesting that writers in the 1690s already believed this to be a very old fashioned and quaint construction.

Samuel Goldwyn, lover of the oxymoron, once said, “Let's have some new cliches.” There's an honest sentiment behind that. No writer parachutes into the landscape of literature without any idea of their surroundings. Cliches aren't just pervasive phrases; they are our point of reference when it comes to structuring a story, expressing thoughts and creating characters. The worst fiction might never go beyond widely used tropes, but the best fiction starts with an awareness of them.

George Dobbs is an MA graduate in creative writing who lives and works in the grim North of England. When he’s not at work on various writing projects, he enjoys cooking, long-distance running and avoiding the weather with his cat.

KEEP READING: More on Writing

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©