-

-

This is part four of Paul Kwiatkowski’s cross-country assignment to investigate alternate perceptions of consciousness. Click here for part one [NSFW], here for part two [NSFW] and here for part three [NSFW].

This is part four of Paul Kwiatkowski’s cross-country assignment to investigate alternate perceptions of consciousness. Click here for part one [NSFW], here for part two [NSFW] and here for part three [NSFW]. -

Wall, South Dakota

-

I stayed in South Dakota for three days waiting for a check to arrive. I needed the break from driving. The antibiotics used to combat Quake Fever had made me lethargic. My feet had swollen from inactivity; they barely fit inside my sneakers. Flickering lampposts passing over the freeway bounced against the inside my eyelids keeping me from sleep.

Along the highway there were zero options for healthy food. You knew it was bad when McDonald’s was the safest choice; their “food” was so processed no bacteria could possibly thrive. Throughout the years, my body had grown an immunity to their brand of feed. The McSalad was never an option. To mask the taste of beef confections and salty fries, I doused everything I ate in the Taco Bell hot sauce I’d been hoarding. Since leaving Los Angeles I gained so much weight that the only pair of pants I could wear were sweats. A thin, constant sheen of sweat built up over my skin like the frost on a chilled vodka bottle.

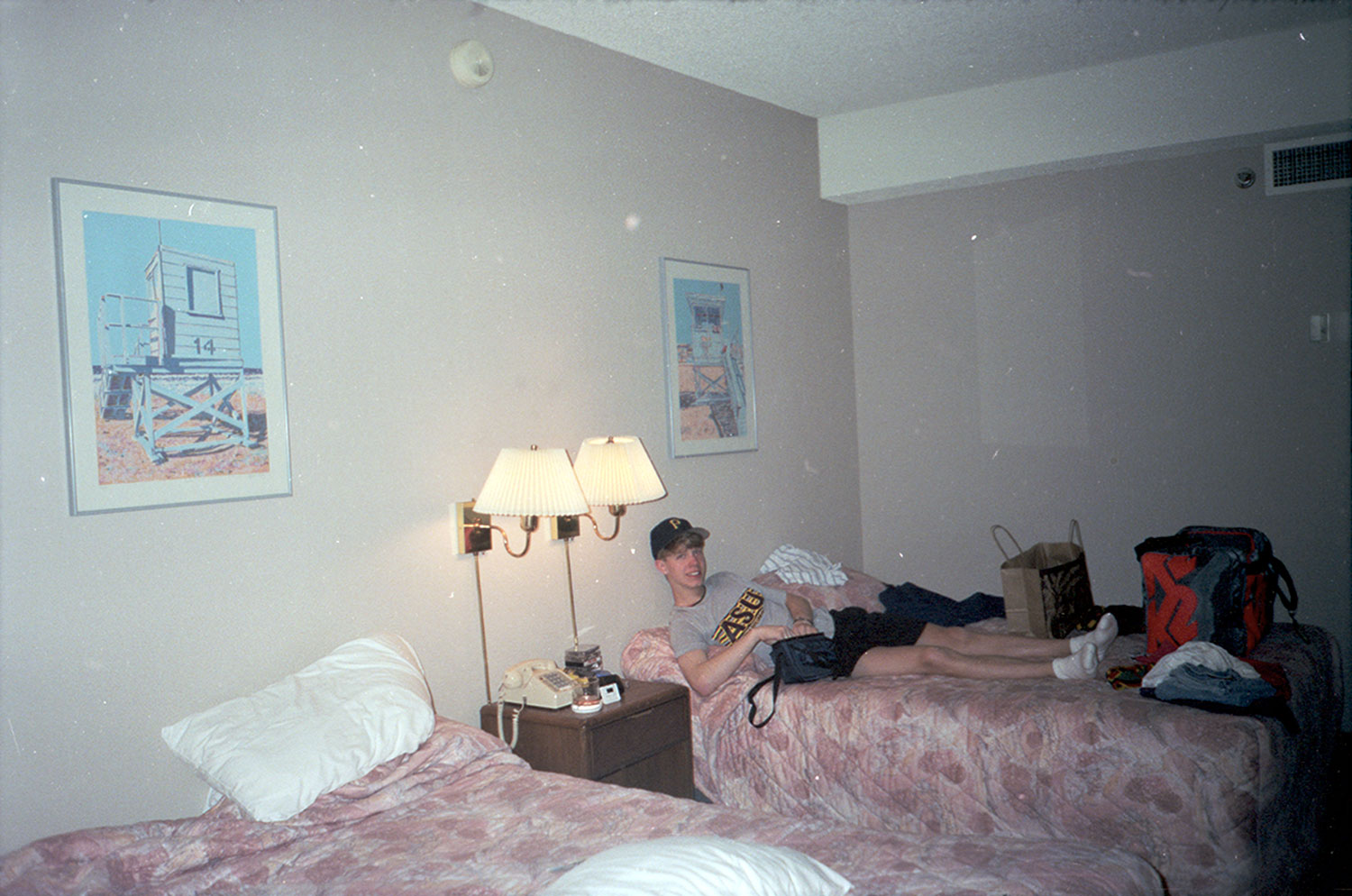

Motel 6 was the only place I could afford with a “gym” — a repurposed guestroom with a semi-functional treadmill and bench press. I committed myself to maintaining a very loose fitness regiment of indoor cardio.

-

While on the treadmill I spaced out to a television mounted at eye level over the inner console. Turning it off meant running towards a blackened, eyeless reflection of myself. Out of three working channels I settled on TLC, an entire network dedicated to the vestiges of America — the obese, the addicted, the baby beauty pageant families as well as the fringe religious groups.

My 600-lb Life was playing. A morbidly obese woman is offered double gastric bypass surgery in the hopes that she can regain ownership over her life. Aside from sugar cravings, the only thing standing between her and her weight goal is her husband, a Brit she met through a dating website that connects chubby-chasing Europeans with obese Americans. Through a series of old photos, we see her on vacation somewhere in the Mediterranean, jammed into a jacuzzi with several pale, skinny men. At a glance the image looks like a vat of boiling white eels. Her husband is unhappy about his wife attempting to lose weight. This is not the American dream he bargained for.

The reality of the woman’s struggle and the real dynamics of her relationship are left to our imagination. Anything illuminating about her self-imposed paralysis or the challenge that surgery poses to her marriage is buried beneath layers of quick editing, poorly composed music and forced whimsy. The show functions as a blank check designed to make viewers feel better about their own follies. Our appetites make us American. No one pities the insatiable.

-

I retreated back to my room not knowing what to do with myself. There was nowhere within walking distance I wanted to be. I hadn't had a human interaction for days. The isolation of traveling cross-country alone made me skittish around strangers. My social skills eroded. I hated to admit it, but I was lonely. Over Skype I reached out to a friend living in Colombia.

I met Tom shortly after losing my job in 2007, right before photojournalism as an industry was gutted and right before the recession hit critical mass. Tom had left the States that year after marrying a Colombian woman named Ana. I remember him telling me that he was in love and needed time to figure out what that meant. Recently, his mother in Minnesota had sent him a shoebox of old prints he’d taken from 1991 to 1995, incidentally while on the same road trip I was taking.

Late at night I sat in a dining hall outside the motel’s lobby. Tom and I spoke online, drank beer and exchanged photos via email. Two years ago I would’ve laughed if I saw someone doing this. I never felt comfortable on Skype until I learned how to turn off the camera function.

-

-

-

Paul Kwiatkowski: When you finally left the United States for Colombia did you feel like the desire to stay adrift had finally gone away? Or was it the same as arriving in any other city in America?

Tom Griggs: I guess it felt like I had finally fulfilled some sort of destiny. I traveled a lot in life. The thing I hadn't done was an indefinite long-term stay. ... There’s the question of can we start over mid-life or do we carry too much of ourselves to move forward. I was trying to know how much of a clean slate I really had.

I can agonize a lot over small decisions in my life, but with a decision like moving to another country with a girl you love, you just have to say fuck it and see what happens. Making these large-scale choices can sometimes be easier than wading through daily choices.

Did the feeling of being adrift ever go away?

I think so. Definitely, actually. I had endless experience in meeting people and developing relationships with a place, then cutting those roots again and again. Eventually I wasn't sure it was healthy anymore. I’d perpetually gotten to a place of letting everything and everybody go, and finishing a process just to rip it out and start again.

-

Medellin, Colombia

-

-

-

-

Tom’s photos of his new life in Medellin became surrogates for ones I had lost. A past world closed in around me.

-

Brooklyn, New York (2008)

-

I was muscling through daily pangs of anxiety after being let go from an office job that kept me financially afloat. The company had gone under. Photojournalism as an industry was being phased out.

Fear of financial ruin motivated me to apply for jobs I hadn’t considered since my early 20s. I worked as a bus boy at a nightclub and a bartender at a local dive. I sold psychedelic mushrooms that I bought from a grower in Vermont to Brooklyn weed dealers in bulk. I did landscaping for a coke-head boss who once randomly asked me if I thought World War II was “over the top.”

After several months of trying to find a serious job, I’d spun out all the possibilities of work that could support me living in New York City. With zero savings, my severance would be blown on rent and utilities within a month. The only option was to give up my apartment, collect first and last month’s rent money, sell whatever shit I couldn’t pack into a friend’s basement and live week to week cashing in unemployment benefits online in South America.

I booked a plane ticket into Colombia and a return flight three months later out of Rio de Janeiro.

-

All of my photos from those three months were stolen during a bus hijacking in northern Ecuador. The only possessions of mine that weren’t taken were the book I was reading (My War Gone By, I Miss It So by Anthony Loyd) and the Polaroid I used as a bookmark.

I’d also fallen in love with a Colombian girl but never acted on it. Along with all my belongings, I lost contact.

-

Wall, South Dakota

-

-

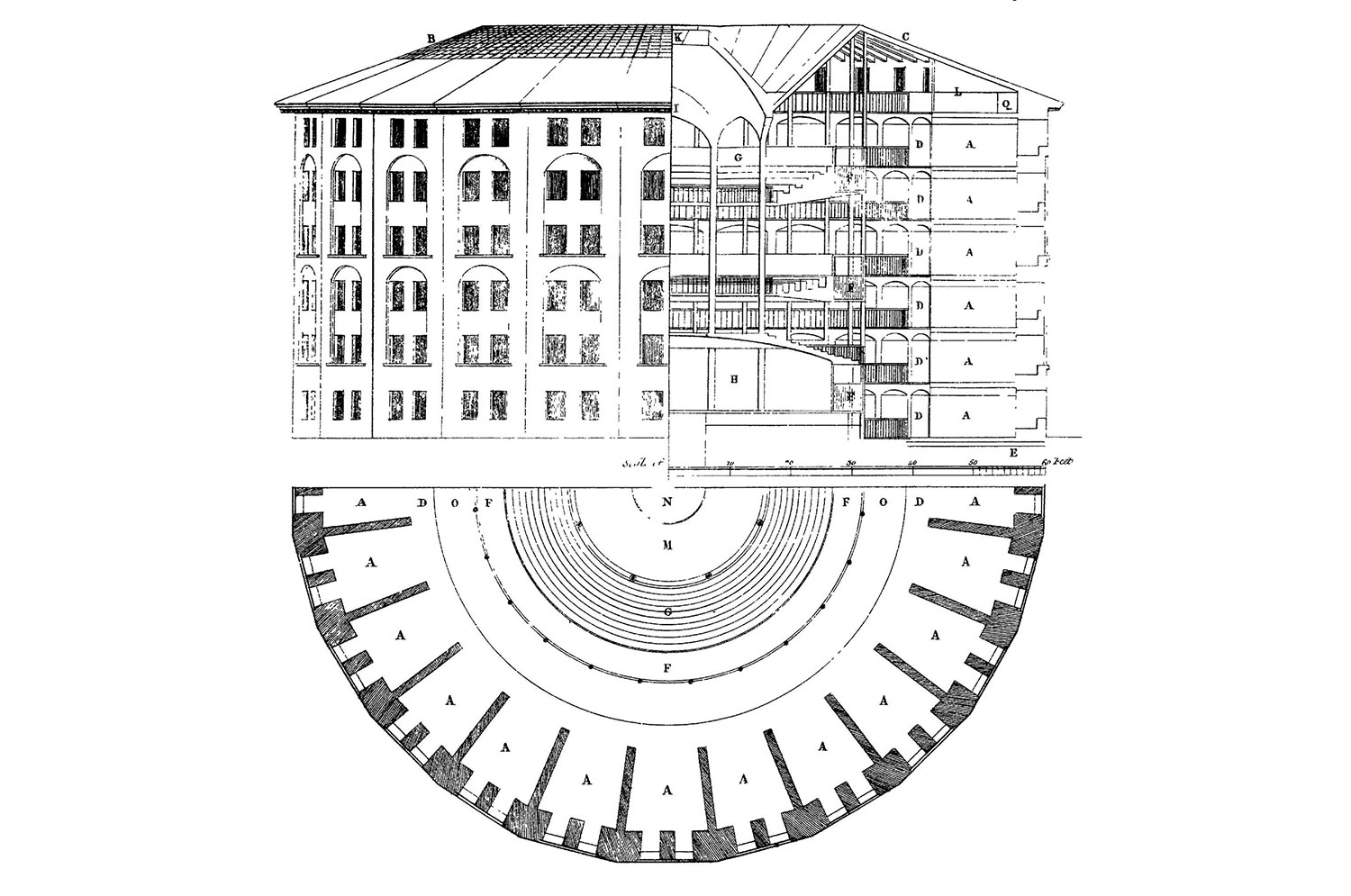

The Panopticon is a kind of prison that allows a single watchman to observe all of the inmates without them being able to tell whether or not they’re actually being policed. It’s impossible for the watchman to see all of the inmates at once, but their uncertainty about when they’re being watched forces the inmates to behave like they’re being watched constantly.

-

-

Comparing my iPhone photos with Tom’s film images, we couldn’t help but think that camera phones are eradicating photographic subjectivity. Everyone with an iPhone takes an aesthetically similar photo despite how many filters they layer over it. In a way, the device’s erasure of aesthetic diversity had further Westernized the world. America’s sacred idea of individualism had been diminished through the nation’s own technology. Selfies, Tom and I realized, are part of an emergent phenomenon that we dubbed the “Autopanopticon.”

Thus far on my road trip and into my assignment, the only absolute I’d reached was that we’ll never have direct access to reality. We don't exist outside of ourselves. We’re born having no knowledge about consciousness; it's something we become aware of through science, images, language, interaction and experience. Most of it is determined through culture and geography. Reality is not at one with the mind.

The Autopanopticon is the only reliable tool we have for acting from a unified perspective. It not only posits that we are aware of the world around us through technology, but that it is aware of us.

-

Smoking wasn’t allowed in my hotel room, so I had to light a joint inside my car to clear my head of another episode of My 600-lb Life. I sat on the backseat with my feet propped up between the driver and passenger seats. In front of me, across the lot, a cleaning lady drained a garbage can onto the sidewalk. The slush trickled over to where I was parked and pooled beneath me.

I wondered what life would be like when I got back to New York. I’d been away long enough that it no longer felt like home — nowhere did. When I returned there’d be no certainty, no job or money or apartment or girl. I tried not to worry.

-

-

Part V

Eat Prey Drug: Sweet Charity -

Share on FacebookShare on Twitter

Read More In This Series

Or Buy Paul Kwiatkowski's Book

And Every Day Was Overcast

Out of South Florida’s lush and decaying suburban landscape blooms the delinquent magic and chaotic adolescence of And Every Day Was Overcast. Paul Kwiatkowski’s arresting photographs amplify a novel of profound vision and vulnerability.

$29.95

Eat Prey Drug: Motel 6

Text and Photographs by Paul Kwiatkowski with Tom Griggs