The Weird, True Story Behind Good Speech (a.k.a "Theeeeaahtah Voice")

Writing about Chicago's Backroom Shakespeare Project, a collective of actors that performs Shakespeare for free in bars, I stumbled on something that sounds comically irrelevant: the world of theatrical dialect coaching. But there is a debate in this world of voice and speech teachers (a.k.a VASTA; don't worry, I'm in deep now) that's been going on for half a century, a debate about the use of one particularly controversial and pervasive theatrical dialect that will change the way you listen at the theater.

I don't go to plays much. I am not an actress. I auditioned once for Romeo and Juliet in high school because they made me because I was fat and funny. I flunked the audition because I couldn't stop laughing at the fact that the word for breast was "dug." What is anything if a breast is a dug? I can't get get a foothold in a universe in which chicks have dugs, I thought. I'm also just a terrible actress. Yesterday I told someone I would meet him for drinks later and he said "OK, so you're not meeting me for drinks."

"When you hear Julius Caesar in Julius Caesar talking like Doctor Frasier Crane in Frasier, that's an actor trained in Good Speech putting it hard to work."

Samuel Taylor, who co-founded Back Room Shakespeare, thinks that people have a better chance of figuring out what a dug is when they listen to old-timey-talk (my words) if actors are not speaking in this strange dialect variously called Standard American English or Good Speech, which many theater companies impose on their actors. When you hear Julius Caesar in Julius Caesar talking like Doctor Frasier Crane in Frasier, that's an actor trained in Good Speech putting it hard to work.

The story of Good Speech begins in 1918, when William Tilly, an Australian phoneticist who had trained in Germany (he was punctilious, a lover of discipline) settled in New York City after a few peripatetic wartime years and began to teach speech courses at Columbia University. A phoneticist was someone interested in the then-burgeoning science of the written transcription of vocal sounds for purposes as varied as anthropological language study to foreign-language learning. In New York he primarily promised foreigners that phonetics could teach them to speak English properly, just as in Germany he'd taught Brits to speak German with his sound-centric method.

But in New York Tilly's practice began to veer away from English as a foreign language. Phonetics turned to Euphonetics as Tilly preached the superiority of a dialect he invented called "World English" or "World Standard English." This concocted dialect departed toward British English but stopped somewhere over the Atlantic, truly like a plane out of gas. Its pseudo-Britishness was particularly noticeable in its "uncolored" R's—that is to say, "car" leaned toward the British "cah." This was a way of speaking that signified "education" or "cultivation," according to Tilly. Ironically, no one spoke World English anywhere in the world—it was an artificial hybrid entirely taught through phonetics.

Tilly was a demanding teacher who played power games with his students, including seating them according to ability and drilling them mercilessly. As his students became defensive of his methods when they were questioned, and devoted to him personally, Tilly's classes took on the aspect of a cult. (I'm reminded of Lawrence Wright's Going Clear, which traces how L. Ron Hubbard was able to control the lives of his disciples in part through infiltrating their vocabulary with one he invented; Tilly might have had such power over his pupils by inventing and controlling their speech.)

World English was blatantly aspirational. One of many public schoolmistresses who studied with Tilly and went on to disseminate his lessons in New York public schools when diction was still part of the curriculum in the early 20th century attested that "Good Speech signifies the possibility of readier...integration with, and membership in, the cultured group in which most of us want to live as citizens." One must be prepared, even if one is a poor schoolmistress, a recent immigrant, or an Australian with a mouth full of rubbery dipthongs, should Katherine Hepburn want to sail with one, to agree with Katherine Hepburn that our vessel is indeed yar with a convincingly uncolored R.

The school mistress' quote is from Dudley Knight's thorough account, published in 2000, of how Tilly's fringe cult of invented fancy English infiltrated American acting schools. Knight, for many years a professor of theater at UC Irvine, is Good Speech's most articulate dissenter. He points out that while the idea of Tilly drilling his classroom full of schoolmarms in elocutionary perfection is all very quaint, the New York of the 1920s, '30s, and '40s was at a fever-pitch of foreign dialects as immigrants flooded in and African Americans migrated north. Seen against this background, it's hard not to concede the elitism or even racism of Good Speech, as Knight wrote, "a model of class, ethnic, and racial hierarchy that is irrelevant to the acting of classical texts and repellent to the sensibilities of most theatre artists."

Samuel Taylor agrees wholeheartedly, although the class/race argument seems less important, now, to someone trying to revive theater for young audiences, than the sheer alienating weirdness. Why repress individuality to sound like some Edwardian crank's idea of a class act when you're playing, for instance, a Roman figure written by a 16th-century playwright who probably spoke more like a modern-day Scot? Proponents of Good Speech argue that it can be useful in conveying élite or powerful characters, but Taylor points out that today a politician seeking power actually cultivates a regional accent (winking at you, Mamabear Palin.)

So how did "Good Speech" go from one Australian and his American acolytes aspiring to sound British-ish to a pervasive standard in classical theater?

Tilly died in 1935, and by 1950, according to Knight, Tilly's influence in the academic study of phonetics had dissipated partially as a result of his fringe preoccupation with World English. Edith Skinner, a former actress who had studied with Tilly for five years, starting in the late '20s, adapted his methods to theatrical dialect coaching at Carnegie Tech, where she trained legions of actors and teachers that went on to disseminate Skinnerite methods at other training programs. Later in her career she was a founding member of the theater program at Juilliard. She adjusted Tilly's World English slightly but kept its essential Esperanto-like, artificial blend of American and British English. Lightly applied, it flattens out regional accents and purifies vowel sounds; at the extreme, it's James Lipton gagging on a tongue depressor. Kelsey Grammar, who studied at Juilliard, said that Skinner's Good Speech had gone into the character of Doctor Frasier Crane. Skinner's textbook, Speak with Distinction, first published in 1942 but reissued as recently as 2000, remains in the curriculum at theater schools including the Guthrie Theater's MFA program where Samuel Taylor studied (2002 -'06). Whatever he thinks of it now, he worked hard to master it, as his careworn and marked-up copy of Speak With Distinction shows. Having a written system for isolating and describing vocal sounds does help people understand how to change their speech. It's not just for actors: per an Amazon review, "anyone that requires voice for their livelihood must get this book, especially a hypnotherapist or a presenter."

Even though he loathes the blind application of it in Shakespeare and other classical productions, in the below audio, you can hear Samuel Taylor selectively deploying Good Speech in a passage from Henry V to show Prince Hal's ability to weave between an artificially learned high-class speech and the gutter-talk in which he was raised.

When we finished recording Emily Shane reading a passage from Love's Labors Lost, I caught Taylor laughing. I was confused, since Shane had been reading a passage as far as I could tell about her lover dying in war. "It's amazing how much better you understand what's actually happening. You get it," he said, referring to Shane's rendition in her own speech. Skinner claimed that Good Speech aided a listener's comprehension because it smoothed over the jarring differences in a cast's accents. Taylor argues the exact opposite; that in making speech artificial, it somehow masks an actor's ability to communicate honestly, obscuring even nuts-and-bolts of plot and character. Have a listen and hear for yourself:

In the attached MP3s, you can compare

1. Emily Shane reading from All's Well that Ends Well, Act III, Scene 2, first in Standard American English and then in her natural voice.

2. Samuel Taylor reading the "To Be or Not to Be" speech from Hamlet, first in Good Speech and then in his natural voice.

3. Samuel Taylor reading "the tennis ball speech," from Henry V, Act I, Scene 2.

What follows is a transcript of an extended conversation between Julia and Sam, breaking down Henry V's tennis speech futher.

Julia Langbein: So what kinds of content in the line would make you choose to use this high status speech?

Samuel Taylor: In this case, when consciously claiming the role of king in a very public way. Kelley Ristow, who co-founded the project was giving a tour to some prospective students for our training program at the University of Minnesota, Guthrie program — and she's from Wisconsin, so she was saying [heavy Wisconsin accent]: "The Movement studio is over here…" — and this girl said — "What year are you?" — and she said "Oh, I'm a saph-more" — and she said "Oh good, when are they going to beat that accent out of you?" and Kelley turns to her and says [in perfect Good Speech]: "I can speak American Standard English when I need to."

JL: As a power play.

ST: Yeah, it's a power play. So, in a way Henry V is doing the same thing in this speech, using different tones. I appreciate the standard American as a piece of vocabulary to have, but the fact is that it's sort of invaded all of how we [actors] speak. So, for example, he says [in SAE] "But tell the Dauphin I will keep my state, be like a king, and show my sail of greatness when I do rouse me in my throne of France." Like, he's making a very public statement: " I get it — I do play tennis, and I do make dick jokes, but I also, I'm going to conquer your fucking country. I am the king and I will be a king." So that seems useful to sort of say, You want me to play the game of speaking correctly? I can play that game! And furthermore, later I'm going to tell you how your joke is bad. Oh, and also, tell the Dauphin, not only are you a dickhead, but your joke about the tennis balls is also terrible.

JL: Right, so the high-status voice actually sort of means more as a power play when it's contrasted with the everyday or popular voice.

ST: Yeah, and one of the things I find very curious is that in America, our powerful politicians and leaders make every effort they can to sound like hicks. And we are sold Standard American English as a way of attaining high status. "Oh, you're playing a king, you must display high status [with this dialect]." But the reality is, that's not an American cultural thing. In England, there's a way in which society is stratified based on how you speak — there's a history, you know, there's a precedent for that. But in America, there's no argument I can see for—

JL: For eradicating regionality —

ST: Yeah. There's no political figure, there's no person who's actually making a power play on television in my lifetime who's going to speak anything like the way that we're expected to speak during Shakespeare for the reason of showing high status. All the high status people I know have their own really idiosyncratic weird voices that they use. So I feel like there's a strong American argument to be made for killing this weird pseudo British voice that we speak in.

JL: In producing Shakespeare in England — they'd never use this dialect.

ST: I think they've got an easier time of it.

JL: They're native speakers of Shakespeare in a way —

ST: Well, they don't have the same kind of baggage that we do about speaking Shakespeare. I remember there was this genius voice-and-text guy, Andrew Wade, I was talking to one night a bar. I asked, "Why is it that we sound like assholes when we try to speak Shakespeare?" and he said: "Well, your country's too large, isn't it? And it's too young, also." And that kind of blew my mind. Because I was expecting him to blame training programs, but he was saying that you've got this idea that Shakespeare is a religious text, and you've got this idea that your country isn't ready to live up to that kind of thing. So, you're sort of seeking for something, for anything outside of yourselves to make you worthy of it.

JL: So it's about depth and character actually more than it is about dialogue and accuracy.

ST: Yeah, insecurity, really. Like I don't believe that I have it in me to be a King, so I'm going to reach outside myself for this thing. That is uniquely horrible to Shakespeare. Like King Henry, later in the same play, Henry V, he says: "I think the King be but a man, as I am like the violet smells to me as it doth to him." He's got this whole beautiful scene exactly about how the king is just like any of these other guys —

JL: I guess another way of asking this question is: Could rural Wisconsin produce a King?

ST: That's an interesting cultural question [both laugh]. It's like, what way do we [Americans] have of understanding royalty in this country?

JL: Yeah.

ST: I submit that it is not through sounding half-British. Like, whatever way we have of communicating royalty, that [dialect] is the one we've got right now, and it's fucked. It's no good.

JL: These are the last shackles of British colonization that we're finally throwing off [laughs].

ST: Yeah, and everybody talks about how the theater is a really advanced place, where all the avant-garde, new people are. But the reality of it is that theater is consistently thirty years behind, at least, in popular culture — in a lot of political and social ways. And we're still in the 1890s on this.

JL: It's like it's 1779.

ST: Yeah, it's ridiculous! And so, once you take the blue pill, or the red, whichever pill it is you take in the Matrix when you wake up — once you've taken that pill, it's hard to look back and use Standard American English. I feel like I've been infected with a disease and now I'm trying as hard as I can to spread it to everyone else around.

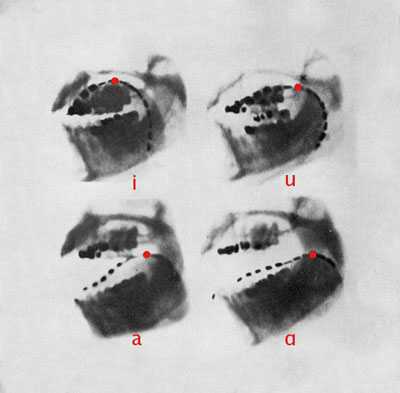

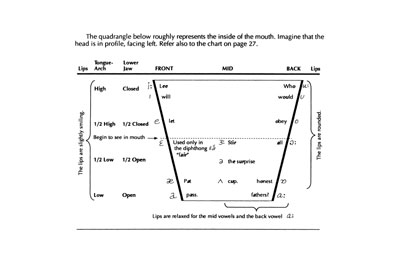

Image credits: Vowel sounds x-ray, Dr. H. Trevelyan George / Wikimedia Commons; all illustrations, Barbara Cleveland Bourland.

When I volunteered last year at Chicago's Smart Museum for a gallery show made out of margarine by German artist Sonia Alhäuser, I discovered that the food art trend is transforming museums from the inside out—their layout and organization, their staff and management—as, more and more, they find themselves literally catering to food as a medium.

From revelations that L. Ron Hubbard personally did the hair and makeup of his hot-pansted teenage bodyguards to a description of Tom Cruise sitting in a Home Depot parking lot guessing at the emotional state of total strangers, Going Clear is a fascinating read. But Wright's achievement goes far beyond (admittedly excellent) gossip: he breaks down the organization's spectacularly empty linguistic structure to show us Scientology's beautiful, vacant house from the inside out.