The Tonys, which will be hosted by Hugh Jackman and televised live on CBS this Sunday, are arguably the most esoteric of the award shows. The 86th Annual Academy Awards had a total viewership of 43.7 million, this year's Grammys attracted 28.5 million viewers, and the 71st Golden Globes drew in its largest audience in 10 years with 20.9 million viewers. Meanwhile, last year's Tonys pulled just 7.2 million viewers — and that made for a good year, the show's largest audience in four years.

And it's not just the numbers that are paltry; there isn’t any mainstream dialogue behind the show either. Log on to Twitter the night of the Academy Awards and you'll be hard-pressed to find a tweet that isn't about someone misreading a cue card or an actor's speech being cut off right when he thanked his dying mother. Log on to Twitter the night of the Tonys and, save for a few outliers, your feed will look like it does any other night. If you wanted to play devil's advocate, you could argue that the Tonys have to compete with the NBA Finals and, in last year’s case, Game of Thrones’ season finale — but let's not kid ourselves. The Tonys are the least watched major awards show because everyone thinks musical theater is stupid.

To be fair, the Tonys tackle both musical theater and straight plays, but musicals receive the majority of the attention. Founded in 1947 by a committee of the American Theatre Wing, the Tony Awards (named after Antoinette "Tony" Perry, co-founder of the ATW) recognize excellence in American theater. Though they’re now a multi-million dollar production, they began as just a low-key get-together at The Waldorf Astoria. There weren’t even trophies, just scrolls and small trinkets (lighters for the men, compact mirrors for the women). In 1967, the awards started to be televised nationally, with double-digit Nielsen ratings (15.4, compared to 4.4 in 2010).

It wasn't until the late ‘80s that the Tonys saw a decline in viewership. The show started to do so poorly that by 2003, CBS threatened to stop airing it altogether, only to announce, that same year, that they would actually be expanding the two-hour broadcast to three hours. Oh, and they would be sprucing it up a bit. They announced that the 57th Tony Awards would be hosted by Hugh Jackman, who, lest he ever let us forget, is not just an action movie star.

With Jackman running the show, the Tonys became an exhausting and tawdry shtick — but a shtick that worked. Jackman went on to host the Tonys for the next two years, then returning in 2009 and now again in 2014.

In an effort to attract more viewers, the Tonys mutated itself into a plasticized shell of predictable song-and-dance numbers. They have become, in several senses, a representation of everything that is bad, boring and corporate about Broadway musicals. At best, they are at least better than the live performances at the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, where actors are forced to perform in a lineup that includes Clifford the Big Red Dog and Elmo. But still, for a night that is supposed to celebrate the medium, the Tonys just wind up confirming all the judgments that are so often launched at musical theater.

Take, for instance, the 2007 Tonys performance of Spring Awakening. Some background: Spring Awakening is a rock musical by Steven Sater and Duncan Sheik, based on the controversial German play of the same name by Frank Wedekind. (The Wedekind play was banned in Germany when it was first released in 1891.) Set in late 19th century Germany, the show tackles abortion, rape, child abuse, teen suicide and homosexuality — and, yes, all of it is set to song. But there were no bombastic lyrics or kitschy dance numbers. Instead, the score was made up of alternative rock songs, performed by an on-stage band and some very gifted teens, including a young Lea Michele (Glee) and John Gallagher, Jr. (The Newsroom).

Spring Awakening was, by all accounts, a revolutionary Broadway musical, especially when you compared it to the three shows it was nominated against for Best Musical: Curtains, Grey Gardens and Mary Poppins. It more than deserved its win. However, the live performance they gave at the Tonys failed to capture what a strange, spectacular show it was. The cast sang a mash-up of three songs, but, because the Tonys are broadcast nationally, had to change and cut many lyrics, including the word "fucked" from the song "Totally Fucked." The result was a bunch of 19-year-olds saying the word "totally" over and over again. Spring Awakening is, amongst many other things, a show about what happens when you are forced to censor yourself; in order to perform at the Tonys, the show had to present a version of itself that directly contrasted the very ideas its based upon. No lyrics were cut or altered from the Mary Poppins Tonys performance. Why would they need to be?

There are, as the 2007 Tony live performances prove, two breeds of Broadway musicals. They each have their place and their purpose. The Mary Poppins type of musical is ideal for going to see with your 12-year-old niece who's visiting the city for the day. These are the musicals your high school performed. They're the ones that make you cringe right before they put you to sleep. They’re the reason you’re so positive you hate musicals. Even Stephen Sondheim, one of the most influential composers and lyricists of the modern musical, regards how ridiculous musicals can be. In a 1997 interview with The Paris Review, James Lipton asks why, in the past, Sondheim has disparaged the lyrics he wrote for West Side Story; Sondheim’s response: "It's fine until you remember that it's sung by an adolescent in a gang."

Book of Mormon

Book of Mormon

The second type of musical is a far stranger bird. Though there are still song-and-dance numbers, there is none of the exaggerated acting and campiness that is so often associated with musicals. Instead, the shows are clever and original. I’m thinking of Book of Mormon, a religious satire created by South Park’s Trey Parker and Matt Stone; and The Last 5 Years, Jason Robert Brown’s two-person show about a doomed courtship that is told chronologically, both backward (from the perspective of the woman) and forward (from the perspective of the man); and Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, which won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. These shows, as well as countless others, are works of art, despite how musicals are inevitably left out of any discussion about fine art.

If it's not clear by now, I am a big advocate for Broadway musicals. But it hasn't always been that way. I actually walked out of the first Broadway musical I ever saw. Actually, a more accurate sentence is that my father walked out, carrying a sobbing, four-year-old version of myself. I did not enjoy Cats very much. To this day I have a Pavlovian response to "Jellicle Cats” and find Anthony Lloyd Webber musicals cloying.

In elementary school, I attended a day camp for musical theater, but my enrollment had more to do with my asthma than any salient interest in musicals. It wasn't until I started a new school in the seventh grade that I began to understand the sardonic underbelly of the American musical. It was then that I was introduced to Avenue Q, a savvy, raunchy show featuring puppet sex, songs with titles like "Everyone's a Little Bit Racist," and the lyric (sung by a closeted puppet who is trying to convince his friends that he does indeed have a girlfriend): "I have a girlfriend/Who lives in Canada/And I can't wait to eat her pussy again."

I was blown away. Before Avenue Q, I only knew about musicals like Anything Goes or Fiddler on the Roof or The Music Man — musicals that were firmly cemented in the Broadway cannon, which I, especially at 12, found boring and tawdry.

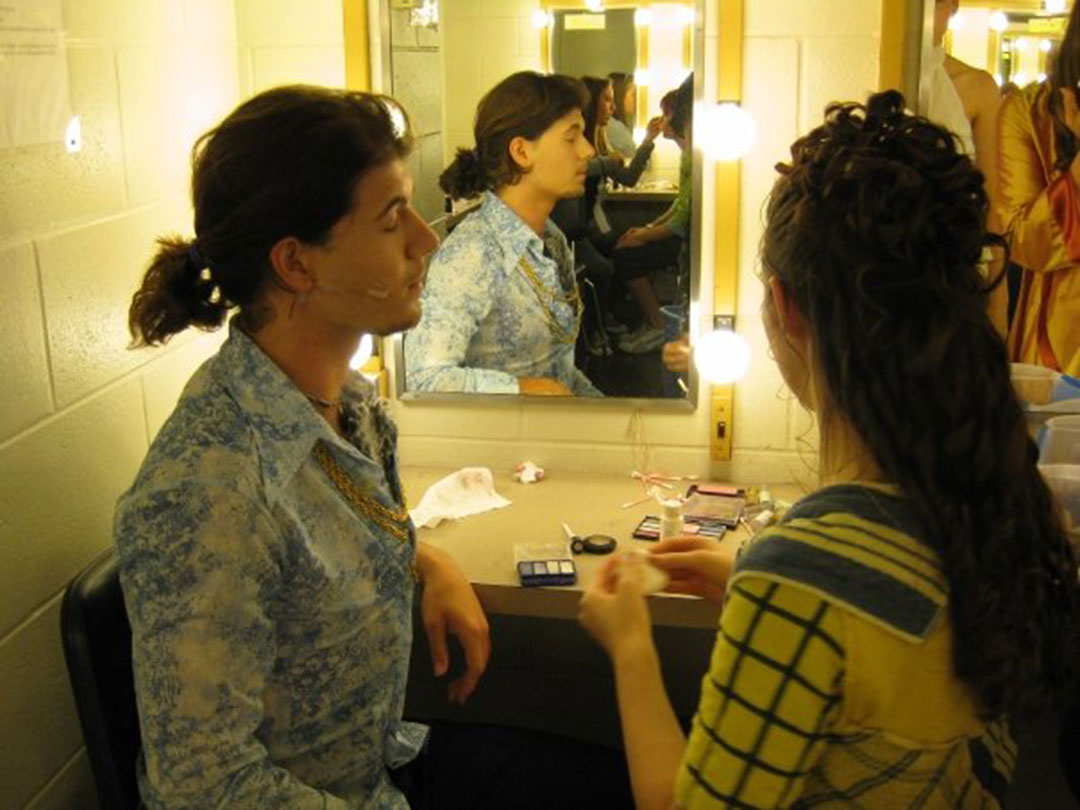

The author (midde) and friends in rehearsal

The author (midde) and friends in rehearsal

Avenue Q opened the floodgates, transforming me from a forced-into-theater-because-I-can't-play-sports kid into a full-blown theater kid. By the time I entered high school, I ate lunch in the black box theater with my other theater friends, often with Rent playing in the background or in between acting out SNL sketches we had seen the weekend before. Outside our small rehearsal space, we were misfit toys. We weren't quite bullied (though 15-year-old boys do sure have a blast with rhyming the word "thespian"), but it was clear we didn't fit in with the majority of our peers: South Florida kids who learned how to inhale properly while smoking right around the time we learned how to inhale properly while singing.

During senior year, a group of boys in my grade were rapping (as you do) when one of my theater friends, Corey, interrupted them with a rap from the musical In the Heights. The musical, which is set in New York City's Washington Heights and includes a number of rap songs, had been released earlier that year. I don't remember which part of In the Heights Corey rapped. It could have been the line "You've probably never heard my name/Reports of my fame are greatly exaggerated" or maybe it was "You're probably thinkin’ ‘I'm up shit's creek/I never been north of 96th street.’" (Considering we were a bunch of Jewish prep school kids from Boca Raton, I truly hope it wasn't "I emigrated from the single greatest little place in the Caribbean/Dominican Republic/I love it/Jesus, I'm jealous of it.”) Whatever it was, the other, more socially adroit boys in my grade cheered on my friend. For a brief, beautiful moment, he was cool.

“Shit, man," one of them said. "Where's that from?"

"This really neat musical," Corey responded, and even I, a proud theater kid, put my palm to my face.

Laughter did ensue, but I don't particularly remember Corey caring what they thought — which is exactly the kind of attitude that allows musicals to happen in the first place. They're in-your-face, unapologetic pieces of art, not at all afraid to be totally obvious. Sometimes they're corny, yes, but they're always honest, which is refreshing when you consider how much of life is cloaked behind four levels of irony.

I was incredibly lucky to go to a high school that not only had sufficient funding to produce three shows a year, but was also run by two incredible women determined to show their students great, though often overlooked pieces of theater. I got my first lessons in feminism when we put on the musical revue A … My Name is Alice. When the school down the street was putting on Thoroughly Modern Millie, we were doing Urinetown, a self-referential show (at one point, a character asks, “What kind musical is this?”) that satirizes capitalism and municipal politics. The show ends with the entire cast shouting "Hail Malthus!" and in order to make sure we fully got the joke, our director made each of us come to rehearsal with a Thomas Robert Malthus quote.

Alas, my relationship to theater was somewhat one-sided. While my friends collected lead roles and, over time, pamphlets to B.F.A. acting and musical theater programs, I was cast in the ensemble. And I didn't even do a very good job at that. When I failed to master the dance routine that opened Urinetown's second act, our director suggested I do an interpretive dance during the number instead. It actually worked, thanks in large to the tone of Urinetown, but I was smart enough to know that I would never be talented enough to do theater professionally. By the time senior year started, I was unofficially retired and worked backstage instead, helping my friends get ready for opening night. It was a timely choice, since that was the year our director selected a fall show with no ensemble: Stephen Sondheim's Into the Woods.

The author’s friends getting ready for opening night of Into the Woods

The author’s friends getting ready for opening night of Into the Woods

If you ever want to make me mad, try calling Into the Woods a musical about fairytales. That is, to put it into context, tantamount to calling Star Wars a movie about space or Harry Potter a series about wizards. The characters of Into the Woods are indeed figures from children's literature, but the lessons they learn and the journeys they take in order to learn those lessons come from the adult world. Case in point: Little Red Riding Hood's solo "I Know Things Now" is about losing her virginity to the Big Bad Wolf. She sings, "He showed me things, many beautiful things that I hadn't thought to explore."

"I've been waiting for the right set of kids to do this show," our director told us during the audition process and many times thereafter. We were, apparently, the right set of kids, both mature enough to understand the more existential themes of the show and young enough to appreciate the playful plot that anchors it. We were: 17, hasty, awaiting college acceptance letters and studying the art of becoming adults in the fastest way possible. All anyone ever told us was that anything was possible, that we could be anyone, do anything. Until then, all we had ever done was grow. We were baby birds without real feathers.

Into the Woods, on the most rudimentary level, is a show about a baker and his wife. After finding out they've been cursed by a witch to never have children, they go to the woods to have the curse reversed. There, they meet a collection of familiar characters: Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, the Big Bad Wolf, Jack (of beanstalk fame) and Rapunzel. They all want what they've always wanted — princes and golden eggs and to get to grandmother's house — but Sondheim and his writing partner James Lapine manage to raise the stakes of these 500-plus-year-old stories.

"There are many versions of Cinderella in every culture," Sondheim says in an interview with The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, "but no one ever suggested, until James, that she left the slipper behind on purpose. If you're a girl who wants to be loved for herself, that's what you do. It's such a wonderful insight and makes the story alive. When you look at Cinderella as a story from the outside: she gets beaten up at home, has to clean pots and brush out the urinals, then she goes to this ball, wearing a beautiful dress and looking gorgeous, and the handsomest and richest man in the kingdom falls in love with her — and she's got a problem? In every Cinderella story, she doesn't just go back to the castle. Why? What's the problem? Well, she's got a problem if she wants to be loved for herself. As far as I'm concerned, that explains the story."

The author’s friend on the night of the final Into the Woods performance

The author’s friend on the night of the final Into the Woods performance

With Into the Woods, Sondheim implemented an existential reality on the characters of fairy tales, and our director urged us to try to answer those questions for ourselves. In the show, Cinderella is asked by her late mother, "Do you know what you wish? Are you certain what you wish is what you want?" She doesn't have an answer, and neither did we. We wanted, yes, of course, to leave our childhood homes, become versions of ourselves separate from our parents and high school. At the same time, children was all we knew how to be. Our world, cloistered as it might have been, was safe. The show we were performing told us that, yes, "Princes wait there in the world, it's true," but it warned us that there were also "wolves and humans, too."

"Stay at home," the witch asks of her daughter Rapunzel, and our parents asked that of us, though perhaps not in those words. "Stay a child while you can be a child," she says, but Rapunzel leaves anyway. There was a part of us that wanted, desperately, to say yes, we will remain children. But we knew we couldn't, and instead, we drew our attention to other lyrics in the show, reminding ourselves that if we were to ever become who we wanted to be, we had to go, so to speak, into the woods.

What we leave in order to grow up (or just grow) is what Into the Woods is really about — children leaving parents, parents leaving children, lovers leaving lovers, our own self leaving and letting go of our past selves. One of the most startling songs in the show is "Second Midnight," which acts as a dialogue between the parents and the children of the show. The children ask, "How do you show them what they want to see while still being true to what you want to be? How do you grow if they never agree to you wandering free in the wood?" In response, the parents wonder, "How do you say to a child who's in flight, don't slip away and I won't hold so tight?"

Reality began the morning after our final production of Into the Woods. I was driving home from SAT tutoring, wanting nothing more than to break 650 on math, when my phone rang. I answered, ignoring my mom's rule about using my phone while driving.

"Are you driving?" It was my friend Jillian.

"Yeah."

"... Well, can you pull over?"

Up until then, a phone call with "bad news" constituted being told I didn't get the part I wanted or that the guy I liked had slept with a girl I didn't like. This was different. Tyler Cohen1 1 Some names have been changed., a boy in our grade, Jillian told me, had been stabbed the night before by Matthew Rubin, another boy in our grade. Within minutes of hanging up, my Facebook newsfeed became a sea of "R.I.P. Tyler" statuses and my phone began to buzz with updates and questions: Had I heard? Did I know?

To pretend I knew Tyler more than I did would be an insult to the people who really did know him and continue to miss him. I have one fuzzy memory of him being at a party senior year and offering me a cigarette. I declined. I was afraid of cigarettes and smokers, of breaking any and all rules. I would never have admitted it then, but I wanted to stay a child while I could be a child.

Act Two of Into the Woods opens with all the characters happy. All those who deserved it got their wishes in Act One, and as they tell us in Act Two’s opening number, they are "so happy." Suddenly there is a loud rumbling noise, followed by an enormous crash. Everyone’s homes have been destroyed — the work, we soon learn, of a giant. "Our friends," the narrator tells the audience, "were about to come upon a force far greater than their collective selves."

My friends and I spent the weeks following Tyler's death having long, dizzying conversations about what had happened. We spoke candidly and listened reverently to whomever else was speaking. As graduation drew closer, we spoke less and less of Tyler, and more of our futures. By the time we finally turned our tassels from right to left, life had started to move faster than exposition would allow. Those who got into B.F.A. programs went, even if it wasn't their dream program. Those who didn't get into B.F.A. programs went to other schools, forcing themselves to carve out other dreams. Matthew Rubin, the boy who killed Tyler, had gotten off on self-defense and was living with his family out West. We talked a lot about how "totally fucked up" that was, then we stopped talking about it. At a certain point, there was nothing more to be said about the matter. It had been an exhausting year, and we were starting to learn that, while every musical we loved has a final number, a resolution, most things in life do not. Childhood might end when you realize there is no narrative shapeliness to life.

I still find myself turning to Into the Woods lyrics in times of need and comfort. My favorite is "No One is Alone," the final song in the show. It has become something close to my own lullaby. The version I have on my iPod is not from the show, but from a concert Bernadette Peters did at Carnegie Hall in 1997. Peters is a deeply gifted singer, but whenever I hit "play," there is a tiny, admittedly biased part of me that thinks her version pales in comparison to my high school's. I used to wish I had a video of my two best friends — beautiful, gifted sisters separated by just one year — sobbing their way through the ballad.

That is no longer my wish. Even if there was a video, it wouldn't do justice to the experience of sitting there, 17 and unsure of where I’d be in a year, watching it happen right in front of me. That's true of any live musical performance, of any live performance, really. You had to be there.

This year's Tonys will feature, as always, televised live performances of the Best Musical nominees, and as always, the cameras will fail to capture what makes each of those shows so special. Anyone who is flipping through channels Sunday night and happens to catch a truncated live performance of Hedwig and the Angry Inch or Beautiful: The Carole King Musical will likely not be convinced that musical theater is worthy of their time or consideration. But, for the 7 million or so viewers who choose to tune in, Hugh Jackman's jazz hands won't erase the genre's powerful and formative influence on our lives.

Michelle King grew up in South Florida and now lives in Brooklyn. Her contributions have appeared on BULLETT, Refinery29 and The Topaz Review. Harriet M. Welsch is still her role model and probably always will be.

(Image Credits, from top: Wikipedia, Tony Awards, Book of Mormon; rest courtesy of author)