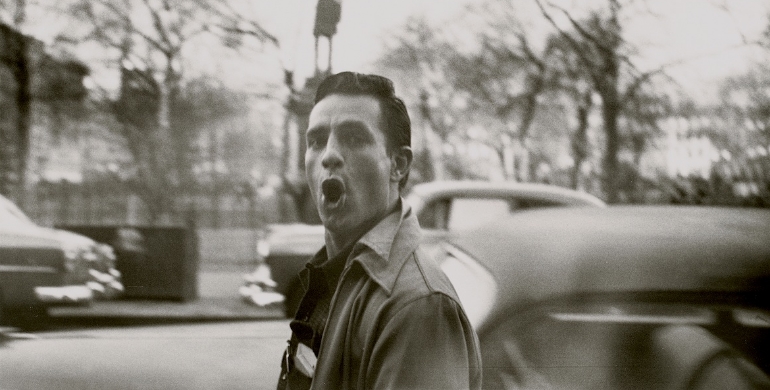

M.R. James (via Alisdair Wood)

M. R. James was an English author, scholar and inspiration to Lovecraft, though the world may have forgotten it.

Montague Rhodes James (1862-1936) was the type of gentleman one doesn’t meet anymore: the very definition of the reserved, erudite scholar who was out of step and out of time. A medievalist by trade, his professional life was closely wedded to the academic world. Specifically, he served as the provost for King’s College, Cambridge (1905-1918) and, more famously, Eton College (1918-1936).

But besides serving budding minds, James’s other great passion was the ghost story. The originator of the “antiquarian ghost story,” he took ghosts out of chains and abandoned castles, and injected them into a more real world. The term “antiquarian” in the “antiquarian ghost story” came from James himself, who used his deep love for the medieval world to the fullest extent in stories that invariably pit quiet academics against the manifest legion of the undead.

A natural conservative with a predilection for outmoded settings brimming with historical consequence, James was an obvious influence on the Anglophilic H. P. Lovecraft, who, in a 1935 letter to science fiction author Emil Petaja, summarized James as a unique talent who flourished under the conventions of weird fiction:

M.R. James joins the brisk, the light, & the commonplace to the weird about as well as anyone could do it—but if another tried the same method, the chances would be ten to one against him. The most valuable element in him—as a model—is his way of weaving a horror into the every-day fabric of life & history—having it grow naturally out of the myriad conditions of an ordinary environment.

James’s Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, which includes “Lost Hearts” (via It’s Dark in the Dark)

While Lovecraft adopted much from James, he did not share the latter’s writing style. Lovecraft’s prose was at times purely purple and light on dialogue, where James’s stories are by comparison concise, fluid and far more naturalistic in speech. The best James stories are truly terrifying, often with a grotesque reveal that can challenge any of today’s torture porn. As a prime example, in “Lost Hearts,” the master of large country house in northern England is proven to be a collector of young hearts. (This is anything but metaphorical.)

Although James could and did excel at stomach-churning endings, his forte was always the cold, quiet kiss in the dark — the icy shudder that consumes readers with otherworldly implications. As such, he was the master of the Yuletide ghost tale and the art of telling spooky stories around the fireplace. In “The Mezzotint” and “An Episode of Cathedral History,” a decaying, cloying atmosphere pervades which is not dissimilar to the feeling that arrives when the long, dark days of winter begin to impinge upon the mind. Some call this “cabin fever,” and its best representation in fiction — Stephen King’s The Shining — is very much James-esque.

James (via Wikipedia)

Because James’s plots are so often set on the rainy coasts of England, in ruined monasteries in the Pyrenees or in airy cathedrals, and also because so many of his narrators and protagonists come from the stiff-upper-lip school of emotionally constrained English Protestantism, his stories have been accused of being lifeless. Lacking in either big or little “r” romance and almost exclusively devoid of love interests or the beasts of passion, James’s oeuvre is much like the man himself. Called “Monty” by the few who knew him well, James was the son of an Anglican curate, and after winning a scholarship to Eton, he would go on to make a life in academia without worldly interruption. His chosen field too required a lonely dedication to dead subjects, and as the master of an all boys’ school, James’s suspended adolescence was exacerbated. Lytton Strachey, the English historian and critic who founded the influential Bloomsbury Group, was no great fan of James’s work; his most damning critique came when he remarked that “It’s odd that the Provost of Eton should still be aged sixteen. A life without a jolt.”

While some of James’s stories run into the realm of unbelievable caricature, he was, if anything, a mature talent, not a composer of magical tales for school boys. And while a story like “Lost Hearts” is built upon re-imagining adult evil from the vantage point of a child, a majority of James’s ghost stories are about older, single individuals who confront even older frights, many of whom are more than just ghosts. In the classic “Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” a vacationing professor stumbles across a whistle carrying a Latin inscription in a Knights Templar preceptory, and upon testing the instrument, he accidentally calls back into the world the malevolent spirit of one the long-dead knights. In other tales, monsters more frightening than ghosts appear, such as in “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book,” which contains a devilish, hirsute beast-man, while “Casting the Runes” features an alchemist who attempts to summon a demon in order to smite his professional enemies.

A solitary bachelor and bibliophile, James was the quintessential writer-as-hermit. He was a man who sought out older times all the while remaining mostly aloof to the rapid changes around him. Because of this, his stories are at once timeless and completely foreign. Even among other horror writers, most of whom cultivated a similar air of eccentricity, James lived as he wrote, and he remains the undisputed king of hushed horrors.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Burlington, Vermont. He prefers “Ben” or “Benzo,” and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Crime Magazine, The Crime Factory, Seven Days and Ravenous Monster. He used to teach English at the University of Vermont, but now just drinks beer and runs his own blog called The Trebuchet.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©