Classical music can be one temperamental bitch.

Take, for example, what recently happened during the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s performance of Anton Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony. One concertgoer (this guy, it turns out) was so disgusted by conductor Osmo Vänskä’s “self-indulgent bad conducting” and the LPO’s “terrible playing” that he stormed out halfway through the performance yelling “Rubbish! ...This is terrible! ... Rubbish!” (Listen for yourself.) Unfazed, Vänskä and the LPO completed the performance without further incident. But try that kind of shit at a Mark Kozelek show and he’ll rip you a new asshole.

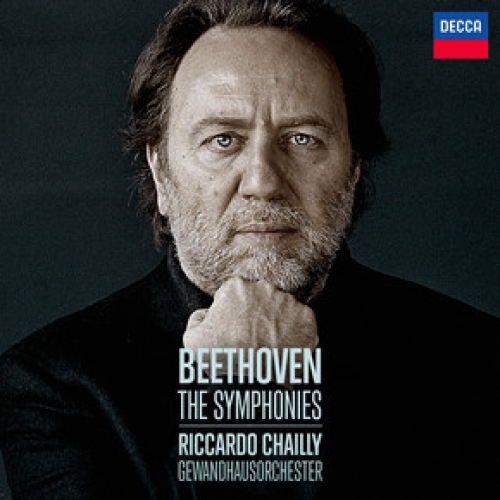

Classical music geeks are famous for their subjective peculiarities. One man’s forte is another man’s mezzo-forte. And there’s certainly no room for compromise—you’re just fucking wrong. Which makes the critical love fest that has followed the release of Riccardo Chailly’s recording of Beethoven’s complete symphonic cycle with Leipzig’s Gewandhaus Orchestra rather shocking. Since becoming music director of the esteemed Gewandhaus Orchestra in 2005, Chailly has solidified his reputation as one of the most accomplished, demanding, and energetic maestros in classical music today—qualities which also helped shape his new Beethoven cycle.

“Superb...joyful...fearless,” beams one critic. “Fresh and bold,” says another.Gramophone magazine, the apotheosis of classical music reviews, boasts that the performances under Chailly’s baton are a “tour de force,” “distinguished,” “electrifying,” and “powerful.” And according to The Guardian, it’s one of “the best modern-orchestra versions of recent times.”

A fan of both Beethoven and Chailly, but no classical music wonk, I can only say that Chailly’s Beethoven cycle is intense and driven, reawakening Beethoven’s music for a new century and the coming-of-age of the Millennial Generation. I also believe it’s something music fans of all stripes should include in their collections. And if Big Boi thinks Kate Bush’s new album is “very, very deep” and “good ride music,” he’ll definitely dig Chailly’s Beethoven.

So here are three simple reasons you, and Big Boi, should check it out.

- Big sounds. Beethoven’s music marked a decisive break with soothing, soporific chamber music that preceded it. Music was now loud, scandalous, unpredictable. Chailly’s recordings unleash the abrasive spirit of Beethoven’s revolutionary aesthetics. Turn it up.

- A Clockwork Orange. With Chailly’s galloping take on Beethoven’s Ninth—a true celebration of life—one can finally grasp Alex’s ode to “Ludwig van’s” final symphony in Burgess’ novel: “Oh bliss! Bliss and heaven! Oh, it was gorgeousness and gorgeousity made flesh. It was like a bird of rarest-spun heaven metal or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now. As I slooshied, I knew such lovely pictures!” Sure, Alex's "lovely pictures" included a bride dropping from the gallows (in the movie, anyway); like I said, classical is nothing if not subjective.

- The cover. It’s just fucking cool. Recently, classical labels have been focusing on making covers more alluring to (younger) buyers. Hence the growing popularity of some classical music hotties. While lacking the drool-worthy sex appeal of a Ryan Gosling, Chailly still looks dapper and fierce as hell in the Avedon-style cover photo. Indeed, Chailly commands your attention. He dares you to listen.

So accept Chailly's challenge and discover what radical Romanticism sounds like.

Image: Gewandhausorchster

Wife: “Can we please listen to something else?!”

Me: “I thought you didn’t care.”

Wife: “ENOUGH FUCKING MAHLER!”

And with that the Adagio of Mahler’s Ninth—one of the most achingly desperate representations of human frailty and mortality in music—is abruptly replaced by the thyroid-thumping throb of Lady Gaga.

Wife (singing): “‘Rah-rah-ah-ah-ah-ah! Roma-roma-maaa!’”

Me: “I got it.”

Wife: Gaga just made Mahler her BITCH!!”

It’s too early for this. I leave the room, put on my sneakers, and head out for a morning run.

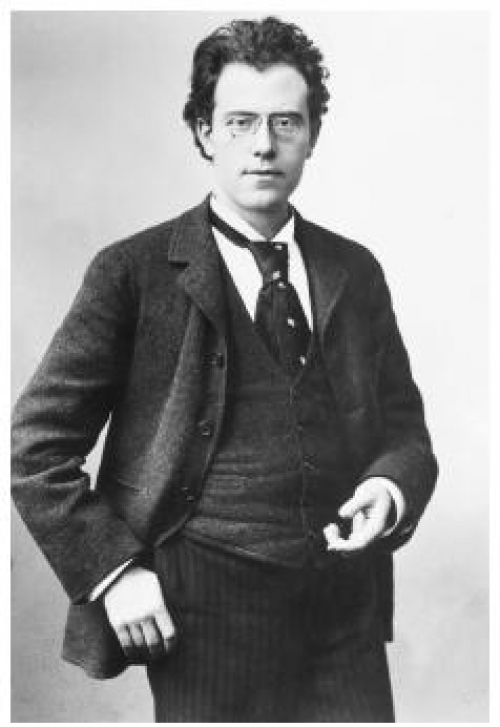

I’ve been listening to a lot of Mahler recently because 2011 marks the centennial of his death. Last year marked the sesquicentennial of the composer’s birth, thereby unleashing two-plus years of geeked-out Mahler hysteria. Orchestras around the world have dedicated multiple concerts to perform Mahler’s works. Special edition box-sets have been issued. Coins have been minted. And many articles, books, and DVDs issued. Along with my fellow deranged Mahlerians, I’ve been blissfully immersed in at all.

Of all that I’ve read about Mahler and his music recently one biographical quirk has been a source of continuing fascination: his estranged brother, Alois, who moved to Chicago sometime in the early 1900s. Essentially disowned by Gustav and his other siblings, Alois moved to the U.S. to begin life anew (he also changed his name to Hans). While little is known about Alois’ American life (he died in 1931), his final address in Chicago, 3931 North Hoyne, is a mere 5 blocks from my house.

Now, on my early morning runs, I will occasionally run past Alois’ old house, in an odd sort of homage to his famous brother and imagine who Alois was and what, if anything, he thought of his brother’s music. Did Alois attend the debut of his Gustav’s music (Fifth Symphony) in Chicago in 1907, or the performance of the Eighth in 1917? Did Alois mourn Gustav’s death in 1911?

Alois’ old house has also become a touchstone of sorts for my own reflections on Gustav’s life, family, and music: How does Mahler’s music reflect his relationships with others? Is Theodor Adorno right that Mahler’s music traces “the history of a breaking heart”?

I believe my polite historical stalking symbolizes a search for a deeper, nuanced, more personal connection with Mahler’s music—a subterranean attempt at exposing the unexposed, of yearning to identify the invisible and forgotten next to the canonized and memorialized, and thereby striving to humanize one man’s music.

Or at least that’s what I tell myself as I run past a stranger’s house at 6:00AM.

(Photo: Corbis)

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©