I am color deficient: red, green, brown and sometimes gray blur into a muddle in my sight.1 Probably because of my troubles with color, I've been fascinated by culture's approach to divvying up the visual spectrum. Which is what makes "The Crayola-fication of the World" so interesting to me. In this super-viral two-part article, Aatish Bhatia describes how Japanese people call green traffic lights blue, even though they have the physical capacity to distinguish the two shades. Still, because of the history of the cultural practice of naming colors in Japan, the green "go" light is labeled blue. Awesome, and strange, eh? It gets better.

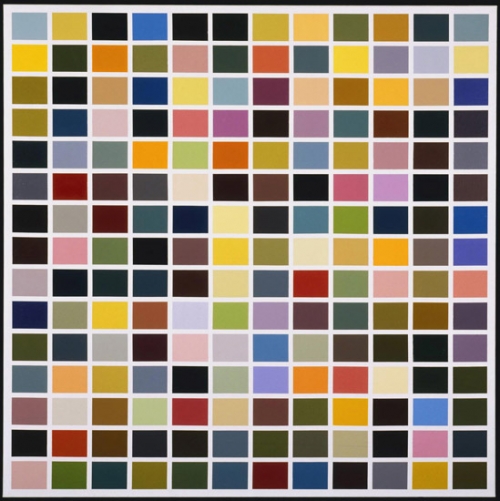

It seems that the development of color words follows a predictable path: you start with two, which in English we might feel as analogous to white and black, and from there you progress to three, which would be analogous to our red (well, yours anyway), and which further progresses until you get to the infinitesimal division of the rainbow.

Looking at the history of colors entering languages, you might feel like it's only a matter of time before English speakers employ a color vocab that makes the big box of Crayolas look puny. Well, rein in that pride: there are limits to your eyeballs, and human perception of color, even that of the freak ladies2 with four color receptors on its outlying limits, is drab compared to that of other creatures. Like the mantis shrimp. Of course, crustaceans don't speak, which means all that vibrant visual acuity is mute.

But I wonder about the forms of metaphor in languages that lack the barrier between colors we know. Would a phrase like this one I dreamt up, the sky, lime-like in midday under a yolky sun, be sensible to a culture that didn't distinguish between blue and green? I'm inclined to think not, because even if we used the same word to describe the color of blue and green things, the sky certainly isn't similarly hued to a lime—it's not like we're calling it plum-like. Which would make it a bad, bad metaphor.

Then again, no one knows what to make of Homer's epically confusing "wine-dark sea."

________________________

1. It might interest you full-spectrum types to learn that total color blindness, the inability to distinguish any color from another, is exceptionally rare; and that we who have trouble with specific color pairs or ranges are overwhelmingly male. Blame it, as I do, on the Y-chromosome.

2. There are a select few women who have an extra color receptor, or cone, in their eyes, which allows them to see further into the ultraviolet spectrum than most of us. Lucky them. Maybe they should paint.

Image: flickr user bortwein75

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©