My first bout with consumption happened in junior high. Tuberculosis has a long literary history, complete with a dedicated Wikipedia listing, but until I wrapped my pubescent mitts around Crime and Punishment, I didn't associate it with consumption. To me, TB meant Mantoux tests and subsequent Masters of the Universe action figures as reward for sitting still. But Fyodor Dostoevsky unveiled a world of impassioned and desperate players, literally “consumed” by the harsh world around them.

Below are three cherished Dostoevskian consumptives, from the physically frail to the societally suffering. Dostoevsky newbies, you'll also find some emblematic quotes to whet your appetites—all from the superior Richard Pevear/Larissa Volokhonsky translations. I've tried to keep it spoiler free.

The Idiot: Ippolit Teréntyev, ailing atheist

My favorite Dostoevsky novel features such enduring characters as the “idiot” Prince Myshkin, a kind, innocent—and widely appraised as “Christ-like”—epileptic, and the bubbly Aglaya (I always preferred her to the femme fatale Nastassya Filippovna). Add to these the iconic, flush-cheeked, suicidal consumptive Ippolit. The 18-year-old's plot-stealing aside “A Necessary Explanation!” contains some of this emotional roller-coaster's most forsaken prose:

Isn't it possible simply to eat me, without demanding that I praise that which has eaten me? Can it be that someone there will indeed be offended that I don't want to wait for two weeks? I don't believe it; and it would be much more likely to suppose that my insignificant life, the life of an atom, was simply needed for the fulfillment of some universal harmony as a whole.

The Eternal Husband: Liza Trusotsky, casualty of circumstances

I'm haunted by Liza, born of a clandestine affair between dashing Velchaninov and consumptive Natalia. Velchaninov senses Liza's suffering and tries to pry her from her abusive, cuckolded “father” Trusotsky. Liza's torn existence between Velchaninov, who truly cares for her, and Trusotsky—who, despite his cruelty, she still loves—resounds in her departure to a foster family:

“Is it true that he'll [Trusotsky] come tomorrow? Is it true?” she asked [Velchaninov] imperiously.

“It's true, it's true! I'll bring him myself; I'll get him and bring him.”

“He'll deceive me,” Liza whispered, lowering her eyes.

“Doesn't he love you, Liza?”

“No, he doesn't.”

She succumbs to fever, and though Doestoevsky never explicitly calls it consumption, the implication of wilting under the world's pressure, abandoned first by her “real” father Velchaninov and then by her booze-addled “father” Trusotsky, is deafening.

Crime and Punishment: Sonya Marmeladov, self-sacrificer

The interplay between sickly Katerina Ivanovna and stepdaughter Sonya evolves consumption beyond illness. While Katerina defies a crowd (“I'll feed mine myself now; I won't bow to anybody!”), coughing up blood before her terrified children, I feared most for Sonya. Her world threatened to “consume” her, as she prostituted to support her younger siblings. Add her unyielding devotion to Raskonikov, the impoverished student behind the novel's murder:

Stand up! Go now, this minute, stand in the crossroads, bow down, and first kiss the earth you've defiled, then bow to the whole world, on all four sides, and say aloud to everyone: 'I have killed!' Then God will send you life again. Will you go?

And...she doesn't break. Altruistic Sonya follows the condemned man to Siberia.

This is why I am hooked on Dostoevsky: for conjuring such compelling “consumptives." Though I may not relate to their hardships like I do Haruki Murakami's everyman boku, it's thanks to Dostoevsky's fully-realized creations that I want to know them. Raskolnikov says it best:

Suffering and pain are always obligatory for a broad consciousness and a deep heart. Truly great men, I think, must feel great sorrow in this world.

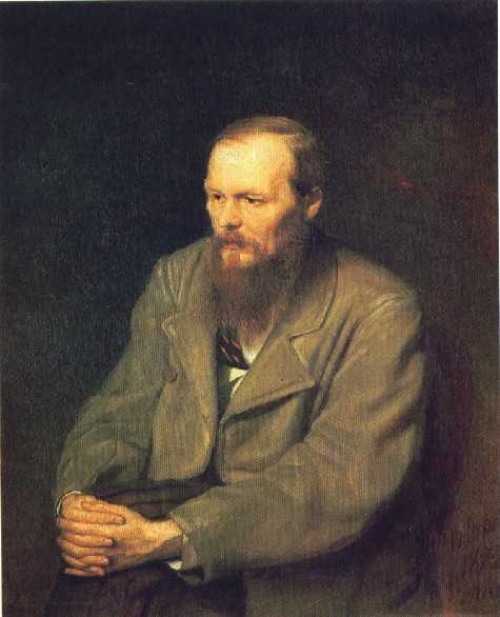

Image: Vassily Petrov's Portrait of F. M. Dostoevsky via Rhode Island School of Design

Some folks make New Years resolutions to drink less and exercise more. This year, I’ve resolved to write better marginalia in the books I read.

In the December 30 issue of the New York Times Magazine, Sam Anderson offers a sampling of his marginalia from some of the books he read in 2011. I admire Anderson for this—it’s like peeking inside another’s intellect and imagination. And his article inspired me to take a closer look at what I write (or don’t write) in the books I read.

I am currently reading Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Which means Dostoevsky’s text is being slowly invaded by my own jottings. I underline, I circle, I draw arrows to connect specific words and phrases, I use exclamation marks to highlight passages I like and large Xs to cross out phrases or plot developments I find obnoxious. And like Anderson, I’m a chronic margin scribbler.

Sometimes my comments are of the ordinary roadmap variety (page 31: “Note importance of physiognomies in D’s descriptions”). Other times, they might point out parallels with other characters/works (page 227: “Note similarities to Raskolnikov’s wandering in C&P) or try to draw out the philosophical depths of Dostoevsky’s story (page 226: “pre-epileptic epiphanic illumination --> higher existence --> fleeting --> sublime moments of infinite clarity and understanding accompanied by suffering”). These notes aren’t intended for some greater end or project (although, come to think of it, it would be interesting to trace the meaning, use, and development of human “strain” throughout Dostoevsky’s novels); they simply represent my brief thoughts and reflections. They help keep me engaged while I read.

Unfortunately, however, I’m a hyper-self-conscious marginalia writer. I dwell too much over the right words, worry too much about trying to express an exact thought. Perhaps I’m also worried about what others might think if they read my scribblings. What if, after I died, a friend came across my marked-up copy of The Idiot? “Why the hell did he write that?" this friend would say. "That wasn’t what Dostoevsky was going for at all! I didn’t know Todd was such a simpleton.” But marginalia ought not be an art of perfection. It should be an informal stream-of-consciousness dialogue with the text. As Rachel recently blogged, marginalia makes reading more participatory and performative.

So as I wrap up The Idiot and begin re-reading The Brothers Karamazov, I’m resolved to become a less self-conscious and more expressive scrawler. Here’s to a 2012 filled with better marginalia.

Photo: Author

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©