It's fun to argue about difficult books (cf. Publishers Weekly's Top 10 and the ensuing comments); it's even fun to read one every now and then. But what about unreadable books—the ones where you can't hope to get to the end, no matter how hard you try? Remember now: we're not talking about long books or simply challenging books. I'm used to those. In college, I had to read War and Peace, down to its dual epilogues, in two weeks; I readUlysses in eight days on a bet. I'm talking outright unreadable.

Here are five books that make JR look like JWOWW.

I love Péter Nádas, but this Hungarian master pushed his first great novel to the limits of the form, and barely made any concessions to readers. Even the brilliant bookseller Sarah McNally says reading it is “like climbing a mountain.” There are two first-person narratives—the memories of a Hungarian man in a love triangle, and his alter-ego in a lightly fictionalized memoir of the first narrator’s own life—and, near the end, a third narrator who punches holes in the first two. I’m a careful reader, but I had a hell of a time figuring out who was narrating some chapters. More than anything, though, the sentences can be downright impenetrable:

“Lovers walk around wearing each other's body, and they wear and radiate into the world their common physicality, which is in no way the mathematical sum of their two bodies but something more, something different, something barely definable, both a quantity and a quality, for the two bodies contract into one but cannot be reduced to one; this quantitative surplus and qualitative uniqueness cannot be defined in terms of, say, the bodies’ mingled scents, which is only the most easily noticeable and superficial manifestation of the separate bodies' commonality that extends to all life functions..."

Okay, the PW people were right to put this on their list. Finnegans Wake(no apostrophe there!) is filled with multilingual puns from European and non-European languages. Your only hope, they suggest, is to read it out loud in your “best bad Irish accent.” I might add the suggestion to pick up Joseph Campbell’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake—then you’ll know that the looping sentence on page 75 boils down to, more or less, “As the lion in our zoo remembers the lotuses of his Nile, so it may be that the besieged [man] bedreamt him still.” There’s a dream-narrative, a long internal monologue, the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section that incorporates thousands of rivers’ names, and quite a few puzzles and tricks to make any regular reading a nearly nonsensical experience. And that's not even getting into the last sentence, which begins what the first sentence ends.

3. Maze

Now we’re getting into more concrete definitions of “unreadable.” Christopher Manson's book is narrated by a strange beast who describes you, the reader, traveling through a maze of 45 rooms, but the maze in question is actually encoded in the book itself—a room on each page spread—and it’s fiendishly difficult (chew on that, House of Leaves). With Choose Your Own Adventure, you can look through all the pages and pick the story you like best. But no matter how many times you flip through these pages, there's no way to just guess your way out of the Maze. The Internet has made this challenge a mite easier, but computers can’t solve the riddles within for you. And even when a shortest path is found through the hundreds of doors between Room 1 and Room 45, there’s another riddle encoded in the random objects within each room. Why was the maze built, though? Why are there so many clues that people once lived there, or can be heard in other rooms? What other riddles remain to be found? The book has been uploaded to the Internet, so go ahead and look.

Okay, so it probably isn’t fair to include philosophy here, but Jacques Derrida devised his writing style specifically to evade any hope of a central, compact conclusion—the premise behind his literary theory, Deconstructionism, being that there no longer exists (if ever there did) a stable organizing principle in any text or system of thought. He did a fantastic job of proving his point with his own words, which famously loop around themselves and move farther and farther away from any truly linear argument. On Grammatology is where he takes that logic to its extreme—even (like modern art writing) to the point of being nearly incomprehensible in translation:

"Let us now persist in using this opposition of nature and institution, of physis and nomos (which also means, of course, a distribution and division regulated in fact by law) which a meditation on writing should disturb although it functions everywhere as self-evident, particularly in the discourse of linguistics. We must then conclude that only the signs called natural, those that Hegel and Saussure call “symbols,” escape semiology as grammatology. But they fall a fortiori outside the field of linguistics as the region of general semiology. The thesis of the arbitrariness of the sign thus indirectly but irrevocably contests Saussure's declared proposition when he chases writing to the outer darkness of language..."

There’s unreadable, and then there’s unreadable. A manuscript from the 1500s written in a script and language that resembles no other on earth, theVoynich manuscript has stumped amateurs and professionals alike. The pages include many strange drawings, from naked women in basins with tubes to plants that do not exist in real life. The Beinecke Library, which houses the original sheets of parchment, says that every week they receive numerous emails claiming to have broken the code, “but so far no theory has held up.” Until that changes, though, the entire manuscript is available on the Internet for codebreakers everywhere to solve.

image credit: Duncan Long, http://duncanlong.com/blog

I first came across Enrique Vila-Matas, whose book Dublinesque drops stateside today, on a cold snowy morning in the Midwest. School was canceled. Work was canceled. And at the top of my pile of books to read wasn't something by Enrique Vila-Matas. Instead, it was a gorgeous Melville House edition of Bartleby the Scrivener.

My back to the frozen world outside, I paged through the story of a man himself frozen in repeating a perpetual, unalterable phrase: “I would prefer not to.” The idea of a man who had moved beyond logic and reason made me shiver in the heat of the fireplace.

What could I read after a such a chillingly final story? I looked down the pile, and my eyes lit on an unlikely title: Bartleby & Co. As far as I could tell, this was the story of a man who had decided to investigate the "writers of the No." Less a novel and more a disembodied set of footnotes, Bartleby & Co. trawls across the literary landscape of figures who, like Bartleby, have gone silent. I read the narrator's skewed commentary on Salinger, and also on Alfau, Derain, Rimbaud, Celan...

So this was who you could read after being overwhelmed by the morass of Modernity, I thought. I looked at the spine. Enrique Vila-Matas. This was the author who found something new and interesting to say about these fragments we have shored against our ruins. How had none of my friends told me about this wildly popular Spanish author, churning out new books about literary sicknesses? (I couldn't even remember how that book had gotten in my room.) I ordered Montano’s Malady immediately, and then waited eagerly for the English translation of Dublinesque.

Dublinesque doesn’t disappoint. In it, publisher Samuel Riba—“he likes to see himself as the last publisher,” Vila-Matas writes—sets out for Dublin to orchestrate a funeral for the printed book, for great authors and the entire “Gutenberg galaxy.” Literature has no plans to die, of course, so the trip becomes a rather complicated affair.

The story takes place chiefly in Dublin and under the aegis of Joyce’sUlysses, but it’s no surprise when John Huston’s interpretation of “The Dead” is mentioned, or when a man strongly resembling Samuel Beckett appears. Still, the author reminds us that Riba “also took up publishing because he’s always been an impassioned reader.” And as Riba is a recovering alcoholic, it may well be that literature is a different sort of addiction for him. If this hall of mirrors, in which every book Riba (or, for that matter, Vila-Matas) has read is reflected back at the reader, seems overwhelming at first, how much more alluring it must seem to the seasoned reader, who will immediately catch the reference to Paddy Dignam or El Jabato.

No book exists in a vacuum, but Vila-Matas’s books are exceptional in their dependence on all other great books to validate their own existence. For people who (like me) don't have doctoral degrees in the humanities, it's a relief to know that there's a rather enjoyable storyline, and a great deal of wit to boot. Still, I can’t imagine anybody liking Dublinesque without having already read Ulysses and most everything else in the Modernist canon—but after Ulysses, Vila-Matas’s Dublinesque seems like one of the few twenty-first-century books worth reading.

image credit: ndbooks.com

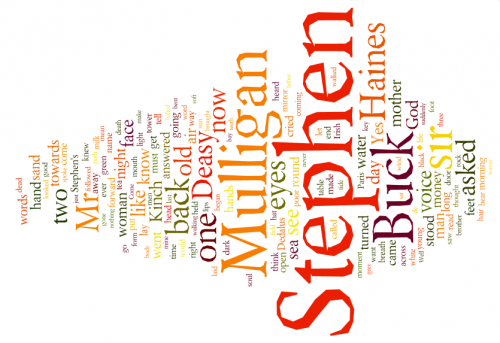

Now that James Joyce's literary corpus is finally in the public doman, I've decided to appropriate it in a singularly 21st-century manner: by readingUlysses chapter by chapter in Wordle, which creates cloud-like infographics based on how often individual words recur in a given text. Visual concordances, more or less.

Each chapter of Ulysses is remarkably different—scholars have noted that chapter breaks serve to shift from one style to another, rather than from one pivotal moment to the next—so I loaded each one into Wordle, let it remove the most common and pedestrian words, and screen-grabbed the results. Here are a few stray observations on the first three chapters, in which Stephen Daedalus's world is fleshed out before Leopold Bloom's arrival.

Chapter 1: Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus (nicknamed Kinch) is talking to his roommate Buck Mulligan in the Martello tower they're both sharing. "God" is mentioned just as often as "mother." The sea and water crop up plenty; the tower is out by the shore, after all. "Mirror" is another popular one, starting with the first line: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." But it's surprisingly renamed in one of Stephen's most famous aphorisms: "It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked looking-glass of a servant."

Chapter 2: Nestor

I've rearranged the words here to keep "Stephen" separate from everything else, since this chapter focuses on Stephen's job teaching, as well as his uncomfortable relationship with the elder Mr. Deasy. There is a great deal of authority and deference in the classroom and in the office: "yes," "sir," and the verbal conjugations of asking and knowing and crying and answering. The word "history" is hidden but memorable here, just as important as books and, ironically, even more recurrent than God: "For them too history was a tale like any other too often heard"; "All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God"; (best of all) "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Chapter 3: Proteus

Stephen's name is all but swallowed up in this chapter, which ditches its protagonist for the "ineluctable modality of the visible." Instead of names, there are his eyes and the sand, everything to see beneath his feet and behind his back. Of all the German words, "nebeneinander" (n:coexistence; adj: in parallel) is the only one frequent enough to appear here. "God" is again recurrent, but not nearly as much as "Paris" or "woman." Everything here boils down to immediate perception and thought, from the concrete elements of the sea and the shore to the clearly abstract mental verbalizations of that which is ineluctable.

I've already read Ulysses once, in an eight-day marathon as a bet with my friends, and while I enjoyed the shifts in perspective the first time around, I wouldn't have thought that the words would mark it out so clearly. I also hadn't thought about Ulysses in religious terms, so seeing the relative prominence of the word "God" in each chapter tells a story I hadn't noticed before.

Cool stuff. If nothing else, with word-clusters like "God Like Mother," "Look Back Sargent," "Eyes Going Kiss," this thing's a band-name factory.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©