The director’s take on the novel isn’t just a translation of mediums, it’s part of his continued exploration of California.

Read MoreThe director’s take on the novel isn’t just a translation of mediums, it’s part of his continued exploration of California.

Read MoreHow did Martin muscle his way to the best-seller's list with A Song of Ice and Fire?

Read MoreMost famous for The Phantom of the Opera, Gaston Leroux was also an accomplished — though now largely forgotten — journalist and short story writer.

Read MoreEnter before August 31 for your chance get this powerful debut novel before anyone else.

Read MoreOn the anniversary of its publication, the final chapter of this Victorian classic continues to baffle.

Read MoreEvery so often, people will ask me why I read so many novels. They sneer: Why don’t I want to know about real life?

Marilynne Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of When I Was a Child I Read Books, writes that she read “to experience that much underrated thing called deracination, the meditative, free appreciation of what ever comes under one’s eye.” Even more fundamentally, she read because she wanted to.

But to fiction skeptics, “Because I want to" usually doesn't cut it. I like nonfiction, sure. James Gleick’s The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood caused me to miss a subway stop. But I don’t care about politics, at least not as much as I should. Or about the biographies of great men and women. Honestly, the Times is all the “real life” I need most days.

Sometimes I read fiction for the sheer beauty of other people’s words. Over winter vacation, I brought along Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty. I came across these lines—

"Far from it," said Nick. "No, no—he spoke, as to cheek and chin, of the joy of the matutinal steel." They all laughed contentedly. It was one of Nick’s routines to slip these plums of periphrasis from Henry James’s late works into unsuitable parts of his conversation, and the boys marvelled at them and tried feebly to remember them—really they just wanted Nick to say them, in his brisk but weighty way.

—and quite suddenly, because Hollinghurst’s writing is so baroque and perfectly rendered, I found myself thinking and speaking with those “plums of periphrasis” for the next week. Other people can’t change my tone like that. The world around me can’t change my thoughts like that.

But the best, the most important reason that I bother with the figments of an author’s imagination is to understand other people. Annie Murphy Paul explains that when we read, we interact with the characters as if they were real. “The brain...does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life,” she explains; “in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings.”

It’s true: I tend to imagine the characters I’m reading a little too well. I had to stop reading Watchmen when Dr. Osterman was destroyed in an Intrinsic Field Subtractor. And when I read Teju Cole’s Open City, I found myself unable to separate Julius’s view of New York from my own. I never had an invisible friend as a child; it looks like books took care of that for me.

Hence my answer: I can read nonfiction to understand how the world works, but I’d rather read fiction to understand how people work. What about you?

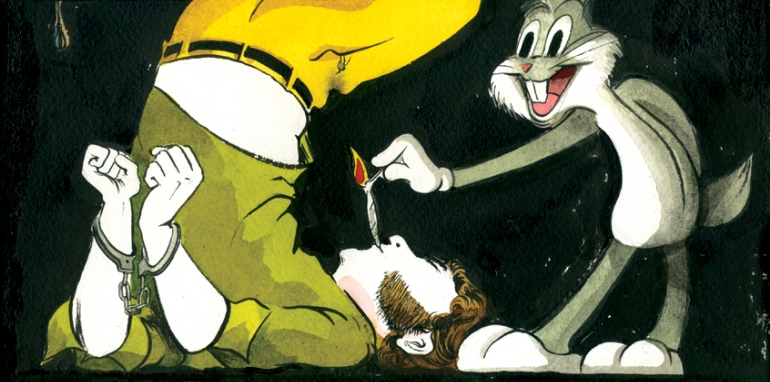

image credit: litfestalberta.org

Several questions came to me while reading Garth Risk Hallberg’s Timesriff, "Why Write Novels At All?" And by "questions," I really mean "moments of skeptical irritation."

To Hallberg, “The central question driving literary aesthetics in the age of the iPad is no longer ‘How should novels be?’ but ‘Why write novels at all?’.” He identifies Jonathan Franzen, Zadie Smith, David Foster Wallace, and Jeffrey Eugenides as the new literary big guns, and then, from what I understand, asserts that the challenges these writers face are not so much questions of form or craft; the new shit to ponder and be judged by is how well the work manifests a sense of connectedness with other people.

Hallberg seems to be saying that these writers have eschewed an exploration of formal principles and standards that would separate themselves from "lower" forms of art. The challenge now, for the, like,super good top literary writers, is to run with this whole empathy thing, making sure not only to "delight" readers, but to "instruct" them as well. But simply because these writers have asked similar questions in and about their work doesn't mean they've ceased to concern themselves with matters of craft. Jonathan Franzen is deeply invested in the style and forms of domestic, realist fiction. David Foster Wallace was an enormous influence on bringing hyper-realism into mainstream culture. These writers have in no way ignored the questions involved in how novels should be.

Another issue I have is Hallberg’s identification of Franzen, Smith, Wallace and Eugenides as writers who are driving literary aesthetics. While these writers are the more literary on the top-seller lists, they are not working in a vacuum. There are other writers at work. Whole pockets of lesser known (even "experimental") writers have been playing with language and style in very serious, exciting, and different ways. They may be on the outer edge of well-known fiction, yet the very fact of their play with language and form pushes its boundaries all the same. To claim that the new "literary" standard is a warm gooey center of feeling surrounded by some sort of message is simply a mistake.

The other boner to be contended with, as far as I see it, is the underlying assumption that the hallmark of "special feelings of togetherness" has usurped formal considerations. Special feelings have always been at work in literary fiction. This whole "not being alone" moralist emotionality has always been at play, in conjunction with formal considerations. Not a dichotomy. Great literature has very special feelings! Great literature stirs very special feelings in the reader!

Screw the whole "message" nonsense (I’d need a whole other post to slog through that wad of sunshine), but feelings! And standards. My god, please, standards, rules, principles. Not everyone can get a gold star. The "age of the iPad" doesn’t change that.

Image: tullamorearts.com