Move over, Cool Britannia, the Olympics have taken London by storm. And when something this crazy happens, everybody's got some thoughts. Including Banksy. Especially Banksy, the world's most famous graffiti artist. Here's the latest swiped from his site (just in case the IOC scrubs away his graffiti), and annotated by the Black Balloon commentariat:

1. [Javelin Thrower with Fully Functional Rocket]

Note the poor form, likely inspired by Hellenistic Greek sculptures rather than contemporary photography of javelin throwers, which wouldn't get the rocket (or javelin) very far. Consider the jersey number, which likely may refer to the gold medalist for the 2004 Olympics women's javelin competition, Osleidys Menendez from Cuba. What can we make of the fact that this winner has been depicted as a white male? Is this an incitement to the athletes to make war, not peace? Or is this a reference to the militarization of Britain, and the sudden arrival of military troops to provide overly thorough security for this event?

2. [Pole Vaulter Over Barbed-Wire fence, with Old Mattress]

Again, the form is terrible: the body should go straight as it lets go of the pole, as this video shows. Even more unnervingly, the vaulter seems to have dramatically overshot the height of the barbed-wire fence, instead of barely surpassing it. Is this England trying too hard to make a spectacle of itself? Is this the organizers grossly overstepping their bounds? The mattress, at least, makes sense: once the Olympics are over, what will remain? Plenty of trash, that's for sure. But hey, I like the creative use of found materials. Nothing says austerity measures like using a dirty mattress.

3. [Sweatshop Worker Making British Flags]

If this is an allegory, we had better pay close attention: who are the sweatshop workers here? Are they as young, and as naive, as the child here? One of my friends sent me this video of Olympic diver Tom Daleybeing doused in glycerin for a photo shoot—and he's barely eighteen. Does the United Kingdom depend entirely on the young, the fresh, and the novel to establish itself? What's happened to history, to everything that makes London different from any other city that has hosted the Olympics?

I'm sure this isn't the last of it. I'll be watching the Olympic competitions all this week, and I'll keep my eyes peeled for more of Banksy's biting commentary. May the best man win.

I am color deficient: red, green, brown and sometimes gray blur into a muddle in my sight.1 Probably because of my troubles with color, I've been fascinated by culture's approach to divvying up the visual spectrum. Which is what makes "The Crayola-fication of the World" so interesting to me. In this super-viral two-part article, Aatish Bhatia describes how Japanese people call green traffic lights blue, even though they have the physical capacity to distinguish the two shades. Still, because of the history of the cultural practice of naming colors in Japan, the green "go" light is labeled blue. Awesome, and strange, eh? It gets better.

It seems that the development of color words follows a predictable path: you start with two, which in English we might feel as analogous to white and black, and from there you progress to three, which would be analogous to our red (well, yours anyway), and which further progresses until you get to the infinitesimal division of the rainbow.

Looking at the history of colors entering languages, you might feel like it's only a matter of time before English speakers employ a color vocab that makes the big box of Crayolas look puny. Well, rein in that pride: there are limits to your eyeballs, and human perception of color, even that of the freak ladies2 with four color receptors on its outlying limits, is drab compared to that of other creatures. Like the mantis shrimp. Of course, crustaceans don't speak, which means all that vibrant visual acuity is mute.

But I wonder about the forms of metaphor in languages that lack the barrier between colors we know. Would a phrase like this one I dreamt up, the sky, lime-like in midday under a yolky sun, be sensible to a culture that didn't distinguish between blue and green? I'm inclined to think not, because even if we used the same word to describe the color of blue and green things, the sky certainly isn't similarly hued to a lime—it's not like we're calling it plum-like. Which would make it a bad, bad metaphor.

Then again, no one knows what to make of Homer's epically confusing "wine-dark sea."

________________________

1. It might interest you full-spectrum types to learn that total color blindness, the inability to distinguish any color from another, is exceptionally rare; and that we who have trouble with specific color pairs or ranges are overwhelmingly male. Blame it, as I do, on the Y-chromosome.

2. There are a select few women who have an extra color receptor, or cone, in their eyes, which allows them to see further into the ultraviolet spectrum than most of us. Lucky them. Maybe they should paint.

Image: flickr user bortwein75

Craig Mod sings a funeral dirge for book covers, yet another beautiful casualty of the shift toward digital distribution of “books.” Because they have lost their purpose, covers must die: as bookstores finally succumb to the efficiencies of Internet distribution, book covers themselves will lose the emphasis they currently have in the publishing world. Instead, clever designers will continually tweak covers—or app icons?—to leverage the characteristics of whichever particular method of distribution—Kindle, Apple Store, whatever—to their favor. Or so it would seem.

I wonder about this. I'm not so sure that major publishers will be keen to give up the "branding" achieved by iconic cover design. While Mod is definitely correct that the cover image at an Amazon book page doesn’t dominate your impression the way physical covers do when you approach a table display, I think he trivializes its importance. When you search for a book, there is the momentary, all important recognition of a particular cover: I want this edition; I recognize that book. And I bet, as was shown with comprehension and retention of hypertext compared to linear text, that the much vaunted “data” presented to customers on a typical Amazon book page rarely enters memory or affects cognition or purchasing behavior—at least, not as much as the initial impression of recognizing the book’s cover does. Certainly someone at Amazon has metrics on that. [See note on metrics below.]

It is this snap of recognition that makes bestsellers. The industry knows this. Hence, the dextrous marketeers have worked to craft immediately recognizable bestsellers through standardizing distribution channels, optimizing displays, and studying consumers perceptual habits. Marketing departments will want to continue to have control over of each book’s brand, hoping to win the lottery by hitting on the next Fifty Shades of Grey,Harry Potter, Twilight, etc. Covers will still get the most design attention, even if their function and role are in transition for some time.

Still, many of the observations Mod makes about the ghostly controls on electronic books are apt. For instance, the Kindle opens directly to the first page of text—I wonder if publishers make this choice or if it is an aspect of the product they’ve ceded to end retailers, along with price—tucking away the front matter and indicating that the information it contains is of little use to the usual reader. Who knows how to decipher that Library of Congress info, anyway?

Anyway, covers. We may mourn them. They’re doomed because they’re not essential to the non-object ebook. Virtual guts need no physical protection as they’re removed from a virtual shelf and “opened.” And it’s hard to see how methods of preventing remote deletion or emendation of your library would be integrated aesthetically into overall book design.

But fear not. You can still sticker your device.

[Note on metrics: There’s a difficulty in leveraging them as efficiently as possible. Publishers may well be interested doing so through the perpetual refinement of "customer experience" through things like A/B testing. Because of the constant accrual of data about customer behavior that is harvested, there is enormous potential to positively encourage sales. By having two versions of a cover and tracking if either seriously outperforms the other a retail site, marketing teams could, hypothetically, select the cover that performed better and make it, thereafter, the official cover for the book. Problem is, I doubt that Amazon or the other end retailers of ebooks would be enthusiastic about freely sharing the info they gather on customers. So there’d be less integration of data into decisions about which cover did best where. And I doubt publishers will be eager to cede ultimate control over their covers to Amazon, et al. Of course, this isn’t a problem for Amazon’s publishing wing. Then there’s the insidious side of A/B testing. It happens so fast now that marketeers rarely take the time to think about the why B outdoes A in this instance. This is because, essentially, why don't matter. Final causes aren’t as important as immediate effects—namely, money for the company—and so don’t need to be investigated. The danger of this is that marketeers tend lose sight of the fact that they have an impact on the results: you put meat and potatoes in front of a hungry person, they're going to eat it.]

Image: etsy user ilovedoodle

Looking at Liu Wei’s cityscapes made from old school books, I find myself flooded with a familiar sense of reassurance—of the calm that emanated from the cakey volumes on my parents’ shelves and the delicately preserved archives hidden in libraries. I like these cityscapes in great part because I like old books, and I like seeing things done with them.

Of course, I do have requirements. I wouldn’t want to see old books spliced into wet naps or shredded into lining for a bird cage. Shredded into sentence-sized strips to insulate a special gift, however, I might just get behind.

So. What other ways can we ramp up the nostalgic power and the functionality of our old books?

Aromatherapy. One of the most magical traits of old books is their smell. Part dust, part glue, with a dash of mystery, old books smell like a memory of family dipped in a kind of determined hopefulness. Why not treat old books like potpourri? They've already made the perfume.

Hiding your gun. Faux books have been around for a long time, hiding everything from money to drugs, but don’t you think it’s time to put that revolver in some vintage Chaucer? Or, if you're not the "Just Carry" type, take your precious volumes and chop them into guns. What else are you going to do with that frayed copy of Moby-Dick? Make a gun out of it.

Protection. If you’re not prepared to chisel your old books into guns, they can still be used as weapons. The important part is to keep that stack by your front door to make it easily accessible when you need to clobber somebody. Also, if you don’t want to actually assault someone, you can just give them a stack with overzealous encouragement and expect to never see them again.

Insulation/Wallpaper. Okay. Some of the books in my collection I probably won't ever read again. Once they reach a certain age, I think it’d be a fair and lovely thing to paste them to my walls. True, I have lived in several severe weather climates where I've spent a lot of time blow-drying plastic to my windows. But how wonderful would it be to be surrounded by books, not only with slender spines peeking out from the shelves but entire walls of full covers?

While I'm quite capable of throwing away the most precious and sentimental knick-knacks, there's something about books I have a hard time letting go of. If I can class it up and make some art objects that also act as furniture, I could send fewer boxes off to storage.

image: collabcubed.com

Edvard Munch's existential icon The Scream shattered auction records several nights ago. After months of buildup and a televised diss by New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz, The Scream's 1895 pastel (the sole version of four not owned by a museum) sold at Sotheby's for $120 million. Guests posited whether or not it will be headed to Qatar. Me, I wondered if I'd ever see it in person.

I have complicated feelings toward owning art. I “get” that galleries show sellable commodities, a few of which may enter a museum's permanent collection. Most disappear to private collectors, until they return to the auction block or the unpredictable exhibition loan. And I'm not the type who entertains many invitations to visit these collectors' homes, if you know what I'm saying.

Nor am I immune to art-lust. I discovered, waffled about, and ultimately missed my first chance at ownable art in the two-artist show “Finders Keepers, Losers Weepers” at Jonathan LeVine Gallery. I was infatuated withJonathan Viner's ennui-immersed canvas The Fluidity of Power, and for like two minutes I had a shot at it. Stymied both by the price and the thought of fitting the huge thing in my tiny studio, I capitulated. I'm still kicking myself.

I am reminded of one of literature's most scene-stealing artworks: Hans Holbein the Younger's hauntingly skinny painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. It captivated Fyodor Dostoevsky and is a mortal catalyst in The Idiot, where the plot shifts from rosy-glassed Prince Myshkin laughing with the cute Yepanchin girls to tormented Rogozhin musing about putting a knife in somebody. By positioning a copy of this grotesque masterpiece in Rogozhin's flat, the characters effectively splinter into darker realms. Who knows how it would've gone down if they encountered Holbein in Kunstmuseum Basel, where Dostoevsky saw it in 1867 and where it permanently hangs?

I'm mulling another mood-maker: Fix Me Doll by Tokyo-based artist Trevor Brown. It's a 180 from Holbein but right up my aesthetic alley. I've been a fan of Brown's subversive style for years and wear several tattoos inspired by his work. Fix Me Doll was in Brown's latest show in Ginza, Tokyo's Span Art Gallery, and the clock is ticking before another hardcore fan snags it.

Totally more attainable than The Scream, and perhaps more fun to look at? Ah, I'll probably wuss out.

Images: The Scream courtesy Reuters; Fix Me Doll courtesy Span Art Gallery

I find The Paris Review's literary paint chips feature—“paint samples, suitable for the home, sourced from colors in literature”—totally sublime. Their 28 choices, including the requisite Fitzgerald (“Dock Green") and Hemingway (“Elephant Hills”), suggest Gerhard Richter's color-chart paintings: systematic permutations of chromatic variety, as mundane as industrial paint samples yet as thrilling as exploring every possibility of hue and tone.

Okay fine, I'm also an art nerd. So the literary paint chips got me thinking: what happens when you locate these colors in real abstract art?

Think of the possibilities not covered here! Those high-altitude sunsets in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain, or Füsun's tear-reddened eyes in Orhan Pamuk's The Museum of Innocence. The “dead channel” sky of William Gibson's cyberpunk classic Neuromancer could be a flickery gray-green...if, thanks to Gibson's now-retro vocabulary, we can remember what “screen snow” even looks like.

Images: Gerhard Richter courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art; Brice Marden courtesy Wikipedia; Agnes Martin courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York; Mark Rothko courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Byron Kim courtesy James Cohan Gallery

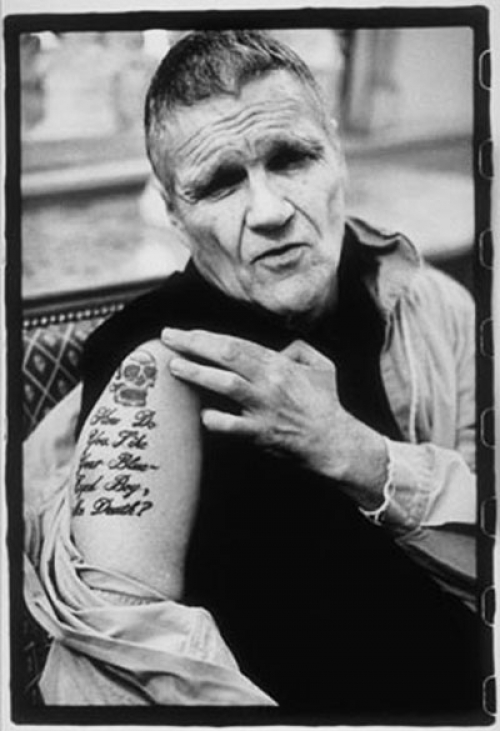

It was with great sadness, and a tremendous sense of unfairness, that I learned of the death of Harry Crews, the Georgia-bred author of The Gospel Singer and A Childhood: The Biography of a Place. The unfairness is somewhat illogical, given Crews’ many years of drinking, fist fights, punishing self-abuse, etc. That Harry Crews should die, even at the age of 76, is not exactly unfair. Nonetheless, we were robbed.

Trying to come up with an appropriate response to my grief-struck sullenness, I decided to take a cue from the man himself. Beyond his literary prowess, Crews was in possession of what I consider to be the very best literary tattoo ever penned and pecked into flesh. On his right forearm, beneath a looming skull, is the ee cummings line, “How do you like your blueeyed boy, Mr. Death?” What better way to pay homage, I thought, than to riffle up some similarly badass literary quotations that would make killer tats? Below is my selection.

It's easier to bleed than sweat, Mr. Motes.

—Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood

Talk into my bullet hole. Tell me I’m fine.

—Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son

What business is it of yours where I’m from, friendo?

—Cormac McCarthy, No Country For Old Men

It wasn’t even me when I was trying to be that face.

—Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

They can’t tell so much about you if you got your eyes closed.

—Ibid.

I am free and that is why I am lost.

—Franz Kafka

Now I can look at you in peace; I don’t eat you anymore.

—Ibid.

But really, you don't have to look any further than Crews' own New York Times obit for killer tat fodder: "Fight On Deadly Rattlers." What other Crews-worthy ink is out there? What tremendously badass quotes should we all brand ourselves with?

Image: coilhouse.net

Inspired by the five hundred fairytales recently discovered in Germany (reported here in the Guardian), I thought it might be fun to take a modern-day tale and twist it, just a smidge, to reflect their style. Erika Eichenseer, the researcher responsible for unearthing the lost German tales, calls them “unadorned” and says “there is no romanticizing.” Fairytales without adornment? Plainspoken fables? I think I know what that sounds like.

Little Red Riding Prostitute

There was once a slut going to college in this wacky town that allowed women to go to college, even though sluts like her only wanted to have a lot of sex. This slut wanted sex so badly, she even wanted the American people to pay for it. Anyhow, one day, her fairy godfather suggested she put an aspirin in between her knees so she wouldn’t have to drag everyone else down with her embarrassing and immoral medical malarkey.

A monster appeared to her and she got all scared and pricked her finger, which happens a lot, I guess. After pricking her finger she fell into a deep sleep and had a dream. In the dream her fairy godfather ate snickerdoodles and watched television while elves bathed together—sinfully. The slut didn’t really know what this dream meant, but she went ahead and followed her fairy godfather’s advice about the aspirin because her fairy godfather influenced lawmakers. After like, two hours she got a wicked cramp and had to go walk it off. Then she got pregnant. Nobody’s paying for that damn bleeding finger, either. Bitch better not need stitches.

Oh dear. Is it time for an apology? Have my advertisers pulled all their spots from my program? The whole point of fairytales are that they in some way instruct people on how to live; or, to paraphrase Eichenseer, the stories are focused on what it means to become an adult. Fairytales provide more than just fantasy. I think a few of our politicians and pundits would be well-served to read some.

Image:trashionista.com

A recent Telegraph post about the relationship between poets and their editors starts off with the nervous subhead, “If one poet edits another, whose work is it?” Tensions arise over the prospect of editors having too heavy an influence, the implications of an incestuous landscape. How can we rest assured that our most treasured poetry is "pure"?

Lucky for me, I am completely unperturbed by this notion of purity. I, in fact, adore quite a few exceptionally heavy-handed editors. I’m also still coming off the glory high I got reading Jonah Lehrer’s article in last week’sNew Yorker about brainstorming, in which Lehrer debunks the myth that brainstorming has to be free of criticism in order to be productive. Criticism and debate have been shown to actually improve creativity. Ha! Criticism wins! Editors are helpful!

So, seeing as how some people could use a little push toward criticism-acceptance, I’ve decided to draw up my top five reasons (with a little help from Lehrer, whom I quote liberally below) we shouldn't fear the red pen.

1. Science says that “exposure to unfamiliar perspectives can foster creativity.” Sure, everyone has something to say. If it's useful, steal it. If it's not useful, it can help define what it is you're not looking for.

2. Science also says that “dissent stimulates new ideas because it encourages us to engage more fully with the work of others and to reassess our viewpoints.” Dissent! Know thine enemy! How better can you position yourself to be the champion? Would you even know about being a "champion" if it weren't for the presence of critics?

3. For the most part, no one is paying any attention. If they are paying attention, they will forget everything you’ve done in less than thirty seconds. There is only so much time you have to engage and really have an effect on someone else, so you might as well try to make it count. Good criticism can help push you toward that effect.

4. For the most part, we are not paying attention. Do you know how many unconscious actions I’ve committed, for years, without knowing? I couldn’t be the first to end a telephone conversation until I was 24 years old—and I had no idea. Or with my writing: how many times in a paragraph do I have to mention a hand touching something before someone shoots me? We all need someone else to tell us what it is we are doing.

5. No one wants to hear you whine. What are you, a baby? Whether it’s the undergraduate with the rambling justification or the man-child distraught because not everybody likes him, whiners are usually too busy suckling on the self-absorption tit to get any work done. Don’t be one of them.

Good criticism can save you from the enormous embarrassment your actions alone will undoubtedly lead you to. So what's the difference between shitty criticism and good criticism? Honest, deep concern for the creative object at hand. As long as the critics you listen to are truly engaged with what it is you’re trying to accomplish—and not just smarmy ass-clowns with ulterior motives—they deserve a good listen. Even the act of turning away can lead to something better.

Image: curmudgeonloner.wordpress.com

"Every once in a while you get the truth from a movie."

—Warren Beatty, 2012 Academy Awards

The Lifespan of a Fact, the new book by essayist John D’Agata and his fact-checker Jim Fingal, has caused a lot of ruckus. The book lays out an essay by D’Agata accompanied by the annotations of Fingal and their correspondence over seven years of working on the project. Fingal is intensely scrupulous when it comes to accuracy and facts, while D’Agata bristles under the procedures of nonfiction—he’s trying to accomplish something else. There's a lot at stake concerning fidelity to the facts,journalistic integrity, the expectations we have toward different forms of art...basically, the nature of truth itself.

Black Balloon’s forthcoming book, Louise: Amended, is a memoir that includes fictional interludes. In these interludes, author Louise Krug assumes the third-person POV and imagines the thoughts and emotions of her family members. This technique bucks the expected boundaries of the memoir form, but by including these other perspectives, Krug has arguably expanded the depth and scope of the memoir’s experience to include a truth larger than the narrator’s alone.

I think the debate concerning nonfiction’s relationship to truth could benefit greatly from the inclusion of texts written about truth and photography. Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, John Berger and countless others (most recently, Errol Morris) have written about the nature of photography: its relationship to reality and time, the intricacies of what exists just beyond the frame, etc. If great artists and thinkers are still grappling with photography’s depiction of reality, isn’t it fair to assume that investigation into the nature of nonfiction’s depiction of reality is worthwhile?

One of the reasons I believe art to be so profoundly necessary is because it functions as a context in which the truth is possible. Or at least provides a context in which the truth is painstakingly sought after, if not quite achieved.

Truth is not always acquired by means of unveiling what already exists in the world. Sometimes, truth is achieved by sheer creation, brought about by something entirely new. I believe both truths—unveiled and created—to be absolutely necessary, and I would strongly oppose any restrictions or impediments to the exercise of either. If D’Agata is playing with a new context (or simply a context that has gone out of style) in which truth might be created, we might just want to pay attention.

image: grokzone.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©