Intrigued by the trend of clothing stores using books as props, as noted by the Paris Review, and peeking into some of the most anticipated books of 2012, I thought it might be useful to provide a kind of style guide that could help readers match their outfits to their reading material. After all, no one wants to be caught on the train reading David Foster Wallace in an Armani suit (reeking of effort) or lounging at the coffee shop in sweatpants reading Joan Didion (too depressing).

The Flame Alphabet by Ben Marcus

The most important thing to keep in mind while preparing an outfit to go along with Ben Marcus’ new novel is that you are not a student at Columbia. Every student at Columbia has already read it, and why are you trying to impress twenty-year-olds anyway? That is gross. Find accessories that make you look older, like a super worn leather book bag (no totes, please), or a sweater that once belonged to your grandfather. Twenty-year-olds totally dig old vintage stuff.

Threats by Amelia Gray

If you’re spending the afternoon at a cafe in Greenpoint and have a lot of scarves, and maybe you even got into that weird feather hair clip thing for a minute but totally don’t wear it anymore cause that was so 2011, you might want to drop Amelia Gray into your tote bag (yes, tote bag).

Hot Pink by Adam Levin

This is one of the few anticipated 2012 novels that you can safely wear sneakers while reading. For the most part, tennis shoes are unacceptable, but choice of footwear is somehow forgiven in the case of Adam Levin. Just be careful: the assumption will be that you’re too intellectually distracted to notice that you’re wearing sneakers, so make sure to look around in surprise every once in a while.

When I Was a Child I Read Books by Marilynne Robinson

Marilynne Robinson is really best read at home, but if you insist on parading her around in public, the least you can do is dress sensibly. Loose sweaters paired with a thin pants and oxfords would do nicely. Be careful not to apply too much makeup; mascara alone should do it.

The Newlyweds by Nell Freudenberger

Even if you don’t own a single item of Chanel clothing, you should look like you have at least one essential go-to Chanel jacket in your wardrobe (likely handed down from a family member) while reading Nell Freudenberger. Any floral print or chiffon dress would work splendidly.

Daniel Fights a Hurricane by Shane Jones

Have you been dying to wear that old army jacket you bought at Salvation Army in 1994, but don’t know how to pull it off without looking like an agro-political grunge throwback? Enter Daniel Fights a Hurricane. The presence of this novel alone will tell us that you’re not on your way to OWS, but rather on a brief hiatus from your time on the internet.

Don’t worry, you won’t have to get a haircut till after you’ve finished reading.

Front image: vulpeslibris.wordpress.com; book cover images: flavorwire.com

Some folks make New Years resolutions to drink less and exercise more. This year, I’ve resolved to write better marginalia in the books I read.

In the December 30 issue of the New York Times Magazine, Sam Anderson offers a sampling of his marginalia from some of the books he read in 2011. I admire Anderson for this—it’s like peeking inside another’s intellect and imagination. And his article inspired me to take a closer look at what I write (or don’t write) in the books I read.

I am currently reading Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Which means Dostoevsky’s text is being slowly invaded by my own jottings. I underline, I circle, I draw arrows to connect specific words and phrases, I use exclamation marks to highlight passages I like and large Xs to cross out phrases or plot developments I find obnoxious. And like Anderson, I’m a chronic margin scribbler.

Sometimes my comments are of the ordinary roadmap variety (page 31: “Note importance of physiognomies in D’s descriptions”). Other times, they might point out parallels with other characters/works (page 227: “Note similarities to Raskolnikov’s wandering in C&P) or try to draw out the philosophical depths of Dostoevsky’s story (page 226: “pre-epileptic epiphanic illumination --> higher existence --> fleeting --> sublime moments of infinite clarity and understanding accompanied by suffering”). These notes aren’t intended for some greater end or project (although, come to think of it, it would be interesting to trace the meaning, use, and development of human “strain” throughout Dostoevsky’s novels); they simply represent my brief thoughts and reflections. They help keep me engaged while I read.

Unfortunately, however, I’m a hyper-self-conscious marginalia writer. I dwell too much over the right words, worry too much about trying to express an exact thought. Perhaps I’m also worried about what others might think if they read my scribblings. What if, after I died, a friend came across my marked-up copy of The Idiot? “Why the hell did he write that?" this friend would say. "That wasn’t what Dostoevsky was going for at all! I didn’t know Todd was such a simpleton.” But marginalia ought not be an art of perfection. It should be an informal stream-of-consciousness dialogue with the text. As Rachel recently blogged, marginalia makes reading more participatory and performative.

So as I wrap up The Idiot and begin re-reading The Brothers Karamazov, I’m resolved to become a less self-conscious and more expressive scrawler. Here’s to a 2012 filled with better marginalia.

Photo: Author

The flight from Los Angeles to Honolulu takes almost six hours, so when I went with my family a few years ago, Swann’s Way went into my carry-on.

Days later, deep in the book, I wondered: What if Proust was Hawaiian? An aging man with an aloha-print shirt eating chocolate-covered macadamia nuts and lying in a cork-lined room to write his masterpiece set in France? And what do Proust’s Hawaiian readers make of his book? If authors can be surprised and even delighted at their readers’ various and unexpected readings of their novels, then I’m inclined to believe that each reader creates an personal canon and reacts to specific works of literature wholly in light of what she or he has read before.

Proust’s A Remembrance of Things Past can be, and often has been, reduced to narrow contexts. It’s been treated as an overtly French work; it’s so easy to relish the names of specific cities and particular French customs. This certainly can be part of Proust’s appeal—the book covers I’ve seen have practically cried out, Pick up the book! I’m sophisticated and glamorous and French!—but to read it as a French souvenir makes the book deeply foreign. Even the different translations reflect this—the more literal translation, In Search of Lost Time, offers a far less dreamy perspective on the French text.

Or there’s the autobiographical reading (did the author really have to name his narrator Marcel?), which could structure the text into “fictional” and “non-fictional” sections.

The tropics revealed a great deal in Proust’s text that the man never would have envisioned. Proust critiques French aristocracy though the Duc de Guermantes’s vulgarities, and Hawaiian readers might well find a parallel to the disdainful divide between Hawaiian natives and non-natives, but the not-particularly-hierarchal relationship between those two segments of Hawaiian society certainly reframes Marcel’s role as an impertinent social critic. Marcel’s weaknesses of memory become both a metaphor and an indictment of Hawaiian culture’s unintentional failure to fully account for historical truth. And when I came across a mention of the high price of quality goods in France, I looked out the window and saw the bewildering price of gas on the island.

I’ve only touched on what might come to light if we looked at A Remembrance of Things Past from the wrong end of a Hawaiian telescope. This is the first in a series of (mis)readings, which will range from considering Victorian literature’s response to AIDS to how Crime and Punishment could be understood if it turned out to have been written by Borges. Keep your eyes peeled, and don’t hesitate to suggest your own (mis)readings in the comments.

Image: aquawaikikiwave.com

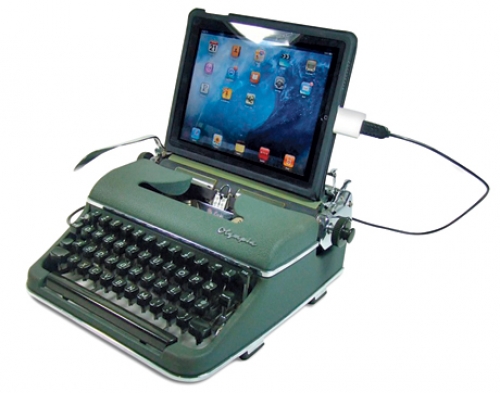

The fantasy-bots in my iBrain started humming after I read this provocative WSJ essay by Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

Read More

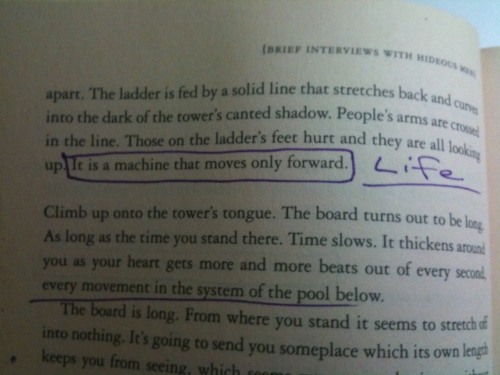

The inner blogosphere of Black Balloon has been abuzz with fake authorial gushiness versus real teen gushiness versus the gush-worthiness of David Foster Wallace faking out teens for real. And this past week, when a package of my old books arrived from my mom, complete with my own teen copy of Wallace's Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, all three confluenced in a cosmic and darkly underscored conclusion.

Read More

I'd nearly completed reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in Japanese when I found this impressive "liveblog" of Haruki Murakami's magnum opus1Q84 on Daniel Morales' site howtojapanese.com. Oh yeah, I thought, I need to get on this. In September 2009, I picked up the first two volumes of1Q84 (volume three was published in Japan in April 2010) and made it my goal to tackle 'em. I noted the English translation wouldn't be out until fall 2011. What the hell, I'll read and translate!

The translation was arduous, funny at times and painful in others. Example: spending ten minutes chipping away at a paragraph, cringing as 睾丸(testicles) gave way to 蹴る (to kick). Another recurring hiccup was Murakami's aforementioned pop culture name-dropping, peppering the text with names like バーニー・ビガード (jazz clarinetist Albany Leon "Barney" Bigard) and トラミー・ヤング (trombonist James "Trummy" Young). I have a newfound appreciation for Louis Armstrong's All-Stars. Plus, I learned tons of vocabulary, which helped hugely in my coursework at the Japan Society (and hopefully impressed some girls). Translating forced me to read1Q84 slowly, savoring each surreal, mundane or salacious passage. It also ensured a very personal way of understanding Murakami's text.

When The New Yorker ran an excerpt from 1Q84 in early September 2011, nearly two months ahead of its English publication, I felt oddly wary. It was "Town of Cats," originally Chapter 8 of Book 2 (and over 700 pages deep) in the Japanese text. Murakami calls this place and its namesake in-text fable 「猫の町」, which I worded as "Cat Town." Now it's in print as "Town of Cats." I suppose both "sound" like a fable, but this simple incongruity didn't sit too well with me. I read "Town of Cats," enjoyed it overall, but now awaited the English publication guardedly.

So guardedly that I've yet to read fully the English 1Q84, translated by Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel. I've spent hours flipping through the pages, remarking on its considerable heft and Chip Kidd's awesome design. But those bits I was worried about? Here's my take on an early passage, from Chapter 1 of Book 1:

Aomame inhaled deeply and then exhaled. She then climbed over the railing while continuing to chase the melody of "Billie Jean" in her ears. Her miniskirt rolled up over her hips. "Who cares!" she thought. If they want to look, let them look. It's not like they're going to see what kind of person I am just from seeing under my skirt. Besides, her firm, alluring legs were the part of Aomame's body that she was most proud.

And the official translation:

Aomame took in a long, deep breath, and slowly let it out. Then, to the tune of "Billie Jean", she swung her leg over the metal barrier. Her miniskirt rode up to her hips. Who gives a damn? Let them look all they want. Seeing what's under my skirt doesn't let them really see me as a person. Besides, her legs were the part of her body Aomame was the most proud.

Incidentally, I didn't add that "firm, alluring" part: that's in the original. It's the little rhythmic jazz, like "railing" vs. "metal barrier", "chase the melody" vs. "to the tune"—inherent in Murakami's words—that's missing in the official translation.

Murakami's classic weirdo teenage girl here is ふかえり, which for language students is written entirely in hiragana (like long-form Japanese script, often seen in some degree in women's proper names). It's her nom de plume, a takeoff from her real name 深田絵里子, or Fukada Eriko. I translated it as Fukaeri, running the sounds together rather mellifluously. That's how it would sound in Japanese! Nope: in English 1Q84, it's Fuka-Eri, overemphasizing that fact she's contracted her given and family names together.

Also: how Fukaeri/Fuka-Eri speaks. Murakami emphasizes her flat, laconic tone by writing her dialogue in only in hiragana/katakana, the two syllabic Japanese writing systems, versus intermingling them with kanji. Here's my version of one of her exchanges with Tengo (the second major protagonist, one of Murakami's most classic thirtyish, slightly clueless males):

"You know me?" Tengo said.

"you teach math"

Tengo assented. "That's right."

"i've heard you twice"

"My lecture?"

"yeah"

There was something peculiar about her way of speaking. Her sentences were scraped of embellishment, and there was a chronic lack of accent, limited (or at least presenting that limited impression to others) vocabulary. Like Komatsu had said, certainly odd.

And the official translation:

"You know me?" Tengo said.

"You teach math."

He nodded. "I do."

"I heard you twice."

"My lectures?"

"Yes."

Her style of speaking had some distinguishing characteristics: sentences shorn of embellishment, a chronic shortage of inflection, a limited vocabulary (or at least what seemed like a limited vocabulary). Komatsu was right: it was odd.

This girl speaks, like, teenage-angsty cool. Even changing that trite "yeah" into a "yes" feels a bit polite. Murakami has a history of writing characters with unusual ways of speaking, like the Sheep Man in Dance, Dance, Dance(depicted in English conversing in long run-on phrases), the plucky old scientist in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (hillbilly accent), and old savant Nakata in Kafka on the Shore (simple English, even simpler than Fukaeri/Fuka-Eri). But how much of their conversational quirkiness makes it into the English?

It's not totally surprising I feel so strongly about my first Haruki Murakami novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which I read in English, and reading1Q84 entirely in Japanese ahead of its English translation. I can practically recite from memory passages from both, and though I'm pleased to have read ねじまき鳥クロニクル belatedly in Japanese, Rubin's English text will forever remain close. I'm sure I will come around to fully reading the Rubin/Gabriel translation of 1Q84, though I'll be unable to shake the notion that what I'm reading is just their interpretation.

Photo: Mr. Fee

A few fun-facts about Haruki Murakami, Japan's most celebrated contemporary author and the man behind the year-end publishing sensation1Q84: he name-drops classical études as frequently as 20th century jazz and rock greats; he once ran a coffeehouse-jazz bar in Tokyo; and he's a triathlete. The man is a well-rounded badass.

I knew little of Murakami when I began reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—some six hundred pages of potent modern-day Surrealism—back in university. Jay Rubin, one of his three longtime translators, handled the English edition, a necessary thing for me then as a just-budding student of Japanese. In addition to the silky prose, I was enraptured by the directness of dialogue and description despite Murakami's continual bending of reality.

I compared Rubin's translation with an earlier one by Alfred Birnbaum, who'd translated the first chapter of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle as The Wind-Up Bird and Tuesday's Women (it originally ran in The New Yorkerseveral years prior but reappeared in the short story collection The Elephant Vanishes), and instantly sided with Rubin. The interplay between Murakami's classic thirtyish male protagonist, Toru Okada, and the author's equally classic weirdo teenage girl, May Kasahara, just felt better in Rubin's words:

Strange, the girl's voice sounded completely different, depending on whether my eyes were open or closed.

"Can I talk? I'll keep real quiet, and you don't have to answer. You can even fall asleep. I don't mind."

"OK," I said.

"When people die, it's so neat."

Her mouth was next to my ear now, so the words worked their way inside me along with her warm, moist breath.

"Why's that?" I asked.

She put a finger on my lips as if to seal them.

"No questions," she said. "And don't open your eyes. OK?"

My nod was as small as her voice.

She took her finger from my lips and placed it on my wrist.

Compare that with Birnbaum's earlier translation. That directness, that humidity-induced curtness, is lost:

Strange, I think, the girl's voice with my eyes closed sounds completely different from her voice with my eyes open. What's come over me? This has never happened to me before.

"Can I talk some?" the girl asks. "I'll be real quiet. You don't have to answer, you can even fall right asleep at any time."

"Sure," I say.

"Death. People dying. It's all so fascinating," the girl begins.

She's whispering right by my ear, so the words enter my body in a warm, moist stream of breath.

"How's that?" I ask.

The girl places a one-finger seal over my lips.

"No questions," she says. "I don't want to be asked anything just now. And don't open your eyes, either. Got it?"

I give a nod as indistinct as her voice.

She removes her finger from my lips, and the same finger now travels to my wrist.

Years later, after moving to New York, I re-engaged my Japanese language studies hardcore. I picked up The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in its original Japanese at Kinokuniya. This was my first attempt at reading novel-length Murakami, and I reveled in it. His prose is delightfully unembellished, and while it will prove difficult to first-time language students accustomed tomanga or Harry Potter in Japanese, I found myself speeding through it. Comparing the original Toru-May passage to the translations, I believe Rubin still captures its mood better than Birnbaum. He nails the girlish, fearless 'tude of May's back-and-forth with this older, slightly naïve guy.

I felt confident that I was reading Murakami as he intended with Rubin's translation. It's a fairly well-known fact that large chunks were excised in the English text (highlighted here in a roundtable email conversation between Murakami translators Rubin and Philip Gabriel, with Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon). Did I miss these sections when I first read it in English? No, but discovering them in Japanese—like an entire chapter's worth—was welcoming. Still, I've spent so much time living in Rubin's translations, navigating well-worn pages, that I return to the comforts of the English-language book without hesitation.

(Part two, on my introduction to 1Q84 in Japanese, to follow)

Photo: Mr. Fee

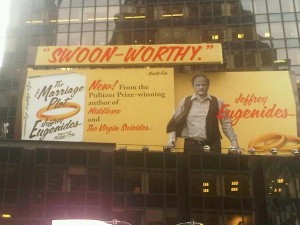

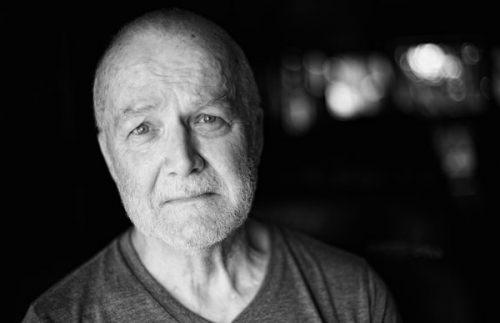

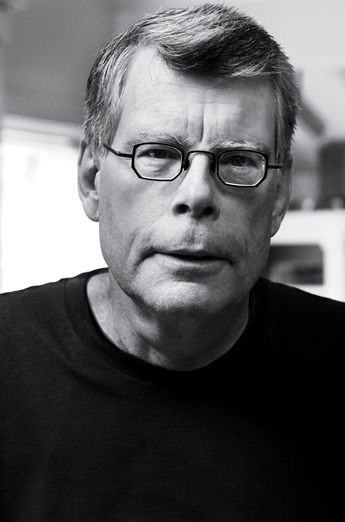

Inspired by the season’s innumerable "best of" lists (and blooming off an earlier post in which I analyzed poets' faces), I decided to take stock of some of my favorite author photos of 2011. For me, great author photos are all about discomfort. The photo shouldn’t convey information about the subject so much as force the viewer to feel uneasy, maybe even squeamish. The goal of the author photo is to make the viewer believe the author has something the viewer must know, that not purchasing and reading the author’s book will have some obscure but detrimental consequence. Here are my top picks for 2011!

Could it be opposite day? Jocks are becoming nerds!

James Franco is flunking acting class!

But back in the normal world, Charlotte Bronte is still the most popular of her sisters

Nerds are pleased with the latest Batman trailer

And the masses have replaced planking with avocado-ing

Writers aren't having much luck though, as poet Carl Sanburg's home is being foreclosed

And Maya Angelou calls out Common for being "vulgar and dangerous"

While the writing world experiences a dearth of scathing wit with Christopher Hitchens's death

Similarly, The music world may soon be without the legendary talent of Etta James as well

World leaders have also been in the obits lately, with the deaths of Kim Jong-Il and Vaclav Havel

But there was one bright note this week: Aragorn has started his own indie publishing press!

Can you believe all of the novels being made into TV shows these days? New books by Jennifer Egan, Chad Harbach, and Karen Russell have already been picked up, not to mention the promise of a new series based on the novels and stories of William Faulkner. Will 2012 the year of literary television? Does television—and by "television," I also mean "the future"—only get better? Sure, novels have forever been adapted for the big screen, but has television ever seen this many books? In that spirit, I’d like to suggest my top five novels I would love to see on the small screen in 2012.

1. Crime and Punishment (Fyodor Dostoevsky). No one is really all that thrilled with Dexter anymore. Maybe it’s time to go back to the insecure, faith-tortured existentialists? There’s only one real murder, but hours of drunk Russians, confession, confusion, prostitution, destitution, cowardliness, callousness, salvation and defeat. Can you imagine the episode (dream-directed by Martin Scorsese) where Mikolka stumbles out of the bar and, with the crowd largely egging him on, beats the horse to death? This is something we need to watch. Michael Pitt can play Raskolnikov—I hear he’s free now.

2. Housekeeping (Marilynne Robinson). Full disclosure: mostly I just want to live in this book. I end up re-reading it because it’s kind of what I want my life to be. Strong but transient women, in a silent house in a town haunted and defined by a lake. There would be such silence! And Beauty! And small, dark moments where we could worry about our grip on reality!

3. Rabbit, Run (John Updike). Haven’t we absorbed enough darkly twisted misogyny and white male privilege from Mad Men? The answer is NO! At least I haven’t. I adore my spoiled brat man-children; the more time we spend exploring what’s wrong with them, the better.

4. Letters to Wendy’s (Joe Wenderoth). This has to be one of my favorite books of all time. Not your traditional novel, each entry could be fleshed out into its own episode—each episode an adventure at that copper-top fast food chain. There is philosophy, there are bodily functions, there is human need, there is meat.

5. Firework (Eugene Marten). Isn’t it time we return to the racist Rodney King America of the early nineties? When we worked in a forms warehouse, got caught up in some violence, and then ran away from it all on a road trip with Miss D and Littlebit? Wouldn’t it be great to have a pre-9/11 enemy again? That enemy being ourselves?

What novels would you like to see made into television? Any ideas on what would make the perfect miniseries? Share your comments below.

Photo: imdb.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©