Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ve been writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 5: South Africa's Riddles

As I read Constance Myburgh’s “Hunter Emmanuel,” [PDF] I was reminded of the literary critic Michael Dirda’s recent Q&A on Reddit:

More than 30 years ago I predicted that mainstream literature would be invaded by "genre" fiction, and this seems to be happening. Writers like Jonathan Lethem, Michael Chabon and others came out of science fiction and comics...I think that we are seeing what SF critic Gary Wolfe calls the "evaporation" of genre lines, and fiction is bursting with all sorts of new inventions and possibilities.

“Hunter Emmanuel” is a hard-boiled detective story torn straight from the headlines of the nineteen-forties. It was published in Jungle Jim, which bills itself as an African pulp fiction magazine. “Hunter Emmanuel” is very much a generic story—not in the figurative sense of being predictable or boring, but in the original and literal sense of adhering to a genre.

Mainstream “literary” fiction itself is a genre of sorts. It is largely realistic, largely psychological, and largely preoccupied with the exacting and poetic use of language. As such, I don’t particularly feel like ranking literary fiction as a genre better or worse than other genres. And that's a good thing, because this story seems to be describing a whole lot more than a detective’s investigation of a disembodied leg in a tree, and the woman the leg came from.

This is a story from South Africa, a country that has experienced splits and divisions of many sorts—political, physical, linguistic, racial. Hunter Emmanuel has decided to figure out how the leg was parted from its owner, why one ended up in a tree and the other ended up in a hospital, and what motives might lurk behind all this. If this story were to be taken as a literary allegory, it wouldn’t be hard to posit that the female represents South Africa in one sense or another, while the male detective is an outsider trying to understand divisive actions already completed. But there isn’t quite enough evidence in this story to complete the analogy. All the same, Jenna Bass, the author and filmmaker who has taken Constance Myburgh as her pseudonym, has expressed openness to such interpretation:

I think many films I’ve made, or written, have political elements, even if not on the same level as The Tunnel; I don’t think you can help it if you live in a country where political decisions are particularly visible. At the same time, I don’t like the idea of profiting off of message-based films.

As with films, so with literature, including the stories in Jungle Jim, which she edits herself. There's clearly much beneath the surface of Myburgh's South African-accented prose, and so I hope the continued adventures of Hunter Emmanuel open doors to more conjectural interpretations.

Here's the story as a PDF: Constance Myburgh's 'Hunter Emmanuel'

Check back for a list of the other bloggers contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: junglejim.org

Looking at Liu Wei’s cityscapes made from old school books, I find myself flooded with a familiar sense of reassurance—of the calm that emanated from the cakey volumes on my parents’ shelves and the delicately preserved archives hidden in libraries. I like these cityscapes in great part because I like old books, and I like seeing things done with them.

Of course, I do have requirements. I wouldn’t want to see old books spliced into wet naps or shredded into lining for a bird cage. Shredded into sentence-sized strips to insulate a special gift, however, I might just get behind.

So. What other ways can we ramp up the nostalgic power and the functionality of our old books?

Aromatherapy. One of the most magical traits of old books is their smell. Part dust, part glue, with a dash of mystery, old books smell like a memory of family dipped in a kind of determined hopefulness. Why not treat old books like potpourri? They've already made the perfume.

Hiding your gun. Faux books have been around for a long time, hiding everything from money to drugs, but don’t you think it’s time to put that revolver in some vintage Chaucer? Or, if you're not the "Just Carry" type, take your precious volumes and chop them into guns. What else are you going to do with that frayed copy of Moby-Dick? Make a gun out of it.

Protection. If you’re not prepared to chisel your old books into guns, they can still be used as weapons. The important part is to keep that stack by your front door to make it easily accessible when you need to clobber somebody. Also, if you don’t want to actually assault someone, you can just give them a stack with overzealous encouragement and expect to never see them again.

Insulation/Wallpaper. Okay. Some of the books in my collection I probably won't ever read again. Once they reach a certain age, I think it’d be a fair and lovely thing to paste them to my walls. True, I have lived in several severe weather climates where I've spent a lot of time blow-drying plastic to my windows. But how wonderful would it be to be surrounded by books, not only with slender spines peeking out from the shelves but entire walls of full covers?

While I'm quite capable of throwing away the most precious and sentimental knick-knacks, there's something about books I have a hard time letting go of. If I can class it up and make some art objects that also act as furniture, I could send fewer boxes off to storage.

image: collabcubed.com

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ll be writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 4: Zimbabwe's Tongues

Melissa Tandiwe Myambo's "La Salle de Départ" [PDF] straddles the uneasy borders between languages. The title, "Departures Terminal" in French, serves as a warning sign: the story weaves between different tongues, recording its characters' rifts of comprehension.

Because Africa is usually portrayed in the media as a homogeneous continent (or even as one enormous country) and because we monolingual Americans read literature in English, it's easy to overlook the sheer variety of Africa's languages. English is certainly common in many countries there—either as a pidgin, or, because of Britain's colonial impulse, as a full language. But so is French (which boasts another prize as good as the Caine), and Portuguese, and Afrikaans. And then there are the native languages struggling against the European incursors, including Hausa, Wolof, Kinyarwanda, and Arabic.

The story opens with Fatima and her father, an old man who "found it easier to read Arabic than French." (It's not uncommon for Zimbabweans to speak two or more of the country's official languages and a few others.) But what language are the different characters speaking? The story is written entirely in English, and we're given few clues that there is a welter of languages until we're told that Fatima's brother "was unconsciously speaking in English...[before] he suddenly realized what he had done and guiltily resumed in Wolof." This kind of information, about each character's unconscious choice of languages, determines their relationships far more than anything they do to each other.

Language itself is a tool for everybody here. Fatima recalls how "as a child she had thought that eating candy would dulcify her words, make them come out sweet as young coconut milk." And it is a matter of convenience: the child, Ibou, moves to America to learn English, but "learned Spanish faster than English and wrote letters home every week in a mixture of French and Wolof."

But sometimes translation is not enough. Or rather: translation simply does not happen. As the story opens with Fatima failing to understand the little things being said, so it closes with Ibou's uncomprehending stare as Fatima reveals that she is staying behind and watching everybody else come and go. We Westerners might not see it immediately, but there are so many languages in Africa, so many cultures jostling up against each other. And even within a close-knit family—father, uncle, son, mother—those languages and lives can drive them apart by their mere difference.

Here's the story as a PDF: Melissa Tandiwe Myambo's 'La Salle de Départ'

And below is a list of the other bloggers contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: map of languages in Africa, wikimedia.org

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ll be writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 3: Malawi's Mavericks

Stanley Kenani’s "Love on Trial" [PDF] is the story of Charles, a gay man caught in flagrante delicto, and Mr. Kachingwe, the man who caught him. In a “kingdom lost for want of a nail” sort of way, the subsequent trial ends up angering donor nations and reducing the country—and Mr. Kachingwe himself—to penury. Kenani, who's already been a Caine Prize finalist (for a story from the same book that features "Love on Trial") is from Malawi but resides in Switzerland and publishes in South Africa. There’s evidence of his multiculturalism in the increasingly large scale of events told here. And the irony of a rumor hobbling the people reveling in its scandal is brilliantly enacted on every level.

Malawi is repeatedly described here as a “God-fearing nation,” a notion Charles dismisses calmly and immediately: “Only an individual can be regarded as God-fearing, but the collection of fourteen million individuals that make up Malawi cannot be termed God-fearing.” According to its 2008 census, 82.7% of Malawians are Christian, while a full 13% are Muslim, and 4.3% are of another religion none at all. At the same time, Malawi has been ranked ninth in the world for prevalence of HIV/AIDS, a fact that holds greater currency for the characters in Kenani’s story.

This is a story that implicates its individual readers in its telling. Charles repeatedly explains that his homosexuality is unexceptional, and refuses to consider it scandalous. If there is any Malawian law forbidding it, he says, or “designed to suppress freedom, then it is a stupid law that must be scrapped.” There is no reason, Charles implies, that his audience should pay any attention to the particulars of his life, except when his dignity is challenged: Nyenyezi, the daughter of the President of Malawi, suggests that Charles’s orientation is a psychological problem, which she could resolve with her love just as her father could resolve his legal problems. We might read this failed courtship as a substitute for the successful and wholly veiled relationship between Charles and his lover, but the vignette is still a story that damns its readers for caring about its tawdry details.

And what of the larger story? Kenani has declared that he wants to inspire other Malawians “to dream big, to have the continent and the world in mind while telling our stories, the stories that make us Malawian.” What does this story say about Malawi? Consider the proverb Mr. Kachingwe’s friend tells him at the story’s end: no matter how great a change may be, whether of a city or an entire country, it is all due to the action, or inaction, of individuals—in this case an alcoholic and HIV-infected man named Mr. Kachingwe, and a single-minded, calm, gay law student named Charles who insists on honor, love, and truth without judgment.

Here's the story as a PDF: Stanley Kenani's 'Love on Trial'

Check back for a list of the other bloggers also contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: Stanley Kenani, storymojaafrica.co.ke

I have been an admirer of Brian Evenson’s prose ever since I drooled over the stories in his first collection, Altmann’s Tongue—one of the top influences in forming my literary aesthetic, and one of the most crucial collections to come out in the last twenty years. His new collection,Windeye, just out from Coffee House Press, continues the same dark, titillating work I first fell in love with.

In very economical ways, and in a very short space, Evenson creates great rifts of uncertainty for his characters and for the reader. In “Angel of Death,” the narrator, wandering a desolate landscape with a group of eight others, is given the task of writing down the names of those who die along the way. But even this concrete task is complicated—made slippery—by larger forces just underneath the tangible world:

The difficulty comes in knowing what is real and what is not. There is no agreement on this. What I am nearly sure is real are bursts and jolts and the smell of singed hair, but others recall none of these effects, recall other things entirely. And how we came to slip from one dim world and its dim deeds to the place where we are now, none of us are in any position to say. And why we are together, this too I do not know.

What I admire most about Evenson is his ability to arrest me in an extreme state of vulnerability. Whether the narrative is in first- or third-person, it never intrudes to provide concrete orientation. I am as lost, as consumed by disorientation, as the characters. In a cinematic sense, it's as if there is no widescreen shot, no panoramic lens, with which to get a sense of any outside environment. I'm pulled into in this great, unresolved tension that becomes the general atmosphere in which the events of the stories take place. Which is horrifying. And delightfully so.

There is also great physicality in Evenson’s vivid descriptions. His landscapes, while mostly spare, contain specificities of texture that make them come alive. Great attention is paid to the scratches and marks of violence upon bodies. These exquisite details are made all the more terrifying for being the only details to really trust.

If you happen to be in New York, I recommend experiencing Evenson firsthand. He’ll be reading with Dylan Hicks and Ben Lerner at the KGB Bar this Sunday, May 20, and at The Center for Fiction on Monday, May 21. I can assure you: horror might await the characters in these stories, but what's even more delightful is the horror that awaits the reader.

image: coffeehousepress.org

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ll be writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 2: Kenya’s Zones

“The Zone” is the locus of Billy Kahora’s "Urban Zoning” [PDF], this year's Caine Prize finalist from Kenya. The story is actually set in Nairobi, a city in Africa known both for its commercial clout and its astonishing nature preserves. And so we see here both commerce and nature, the one inverted and the other subverted as we watch the protagonist Kandle navigate the Zone.

What is the Zone? It is a state achieved after seventy-two hours of drinking. It is a “calm, breathless place”; it is a place both externally achieved through alcoholism and insomnia, and internally achieved by directing one’s mind towards pleasant thoughts. It is an area of strangeness, where the months of the calendar become colored in a synesthetic spasm of Kandle’s mind, and an area of danger, where Kandle’s friends have all succumbed to risky impulses.

I’m reminded of another Zone that takes hours and days to get to, and boasts strange sights for those who make it there: the one in Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker. Tarkovsky amped up the Zone’s vivid colors by painting the leaves of the trees. Why do the film's subjects all struggle to get to the Zone? Because it contains a room that grants its visitors' wishes.

And in the same vein Kandle’s fantasies are fulfilled in his Nairobian Zone: he gets a leave from his work as a banker and so gets money for free; he succeeds in overcoming his deep-rooted aversion to close contact in order to fool everyone around him. The end of the story pulls away from the vividness of Kandle’s Zone to the larger (and stranger) terrain of Kenya proper, and the story ends with two men:

[B]oth laughed from deep within their bellies, that laughter of Kenyan men that comes from a special knowledge. The laughter was a language in itself, used to climb from a national quiet desperation.

If alcohol and little sleep helped Kandle achieve an unusual inner state, so laughter helps the men both make the emotional trip away from the ugly reality of Nairobi’s streets toward a happier place, contained entirely within their minds. Kandle isn’t the first one to have discovered the trick of urban zoning, but he seems to have been the wiliest. The Zone is everywhere, even as the Zone is fleeting. What remains? Kenya, in all its varicolored reality.

Here's the story as a PDF: Billy Kahora’s "Urban Zoning”

Below I'll post a list of the other bloggers also contributing to the discussion on this story.

- zunguzungu

- Stephen Derwent Partington

- The Reading Life

- Backslash Scott

- Ikhide

- Loomnie

- ndinda

- City of Lions

- Practically Marzipan

- bookshy

- Cashed In

- aaahfooey

- The Mumpsimus

- Soulfool

image credit: africa-expert.com

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ll be writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 1: Nigeria’s Possibilities

This was how the world was and there was no reason to think it could be otherwise. But the war came and the bombs started falling, shattering things out of their imprisonment in boxes and jumbling them without logic into a protean mishmash. Without warning, everything became possible.

Rotimi Babatunde’s “Bombay’s Republic” [PDF] is nominally a war-veteran story, but the story is more about the nature of belief. The eponymous narrator arrives on a ship to Ceylon, where he is trained to fight the Japanese. He learns that the native Ceylonese believe he and the other Africans have tails. When he finds his nationality the target of another, worse misconception, however, his reaction is physical; he feels “queasy and [has] to steady his rising urge to puke. That people would imagine he was a cannibal was something he had not thought was possible.”

But the story's carefully engineered revelations are not limited to those of our protagonist. We're forced to realize that the war he fights was quite real—brought to a close with the dropping of nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But this war has not even merited a footnote in our mental history-books. “This is not the Forgotten Front,” Bombay’s platoon leader declares, “and we are not the Forgotten Army. Nobody has ever heard of us so they can’t even begin forgetting about us.”

Bombay returns to his country and home with this enlarged universe of possibilities in his head, and with newly opened eyes he establishes a country of his own. He does not return home to restore order and continue an interrupted story (like Homer's Odysseus) or to reassert authority and direct a story to its proper end (like Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway); he returns to live out a completely new story of his own—a story which is logical to Bombay, but not to his perplexed compatriots.

I suppose I've lied. This isn’t a story about the nature of belief, but a story about stories, and the power they hold over us. Why has this war, which has been narrated repeatedly in books and film, become a “forgotten” war? Why does the author, Rotimi Babatunde, have his narrator focus not on death or religion but on what can possibly be believed? Why does this story open and close with a man who has commandeered a jailhouse in which he voluntarily imprisons himself?

The chair of judging for this year's Caine Prize, Bernardine Evaristo, called for "stories about Africa that enlarge our concept of the continent beyond the familiar images that dominate the media: War-torn Africa, Starving Africa, Corrupt Africa—in short: The Tragic Continent." Does this story succeed in that sense? Does it expand my mental image of what the continent contains? Does it show that Africa is complicated and that Africa is real?

To all those questions, I have to say I believe so, yes, I believe this.

Here's the story as a PDF: Rotimi Babatunde's "Bombay’s Republic."

Below is a list of the other bloggers also contributing to the discussion. Check back for updates.

image credit: The Forgotten War, wsj.net

I don't know whether Maurice Sendak ever explicitly said that imagination should never be limited by false notions of absurdity or risk, but as a kid sprawled out on the floor reading and rereading his books, especially In the Night Kitchen and Where the Wild Things Are, this is what he taught me. The internet does tell me he said the following: “I refuse to cater to the bullshit of innocence.”

I had enough unsentimental adults orbiting my childhood that one of them very well could have told me this. It would have gone over my head at age six or seven. But when you watch a drunk make an ass of himself, hear the laughter elicited by a joke that shouldn’t have been told, or through thin walls hear moans of pleasure that you are years off from appreciating, what you do come to understand, though you cannot yet articulate it, is that life ain't all Green Eggs and Ham.

I’m grateful for coming to this realization early on, thanks to the lovingly irreverent family and family friends who shaped me and allowed me to appreciate Sendak’s stories in all their naked, doughy, beastly glory. As these books make clear, adults can be jerks, escape beats confinement, and "Childhood is cannibals and psychotics vomiting in your mouth!" (The latter was quoted by Art Spiegelman in a 1993 New Yorker strip.) They speak to a truth that the child me did not realize I’d been lied to about yet. I wasn’t old enough to go out anywhere further than the yard, and in truth I never actually wanted to run away. But losing myself in my thoughts and delusions, I could see that this was normal and healthy, something that shouldn't be thought of as a waste of time but a crucial part of being alive.

Like most adults, I still daydream like a kid, though I sometimes wish those mental escapes did not end so abruptly thanks to some adult obligation. But that bullshit is a real part of life, the same as trying to imagine it away. Maurice Sendak’s best work exists in that space between the two worlds, an alchemy of the real and imaginary, which is why it resonates with so many of us.

Image: collider.com

Ernest Hemingway clocking Wallace Stevens. Verlaine shooting Rimbaud. Norman Mailer head-butting Gore Vidal. There’s nothing like reading about writers for whom words just aren’t enough. Even Thought Catalog, the ever-narcissistic barometer of our still-young decade, has begged for more blood, goading today's writers to "replace tweets with kidney punches."

Sending authors on book tours? Yawn. Throwing authors into a steel cage for a straight-up Raw is War-style rumble royale? To quote the late Randy Macho Man Savage, "OOOOH YEAH!" So who should get in the ring?

1. Joyce v. Woolf

First up, the man with a pirate’s eye-patch, and the woman who reduced him to “a queasy undergraduate scratching his pimples.” Let's remember their handicaps: Joyce depended on his wife to help transcribe Finnegans Wake, while Woolf alternately adored and detested her husband. Neither of them was known for being particularly strong, but they both won their fair share of quarrels. In spite of Woolf’s brilliance and formidability, I think Joyce’s familial reliance on liquid courage would be a deciding factor; there’s no way stream-of-consciousness could ward off a drunken uppercut.

2. Austen v. Brontë

The viral video Jane Austen's Fight Club has already hinted at what this fracas would look like. But who wins? There’s no question Charlotte Brontë knew how to inject testosterone into her books: she published under the masculine pseudonym Currer Bell. But she only wrote four novels compared to Stone Cold Jane Austen’s six. All the same, Charlotte wrote about a woman who struggled to gain authority and power despite the men in her life, while Austen’s women are more content to offer scathing commentary about their neighbors. It's close, but my money’s on Charlotte for putting the "brawn" in "Brawn-të."

3. Sontag v. Didion

Instead of a hermeneutics, we need an erotics of writerly takedowns. This is a purely theoretical fistfight, though, since Ms. Sontag has passed away, and Ms. Didion (generously described by Tom Brokaw as “physically frail”) has insisted that working at a typewriter is “the only aggressive act I have, it’s the only way I can be aggressive.” I’m seeing this as a David-and-Goliath thing; I’m sure a typewriter isn’t the only thing Joan Didion could wrap her hands around. I’d bet my collection of signed first editions that Didion would give Sontag a year of magical PAIN!

4. Franzen v. Foer

I don’t usually think of hipster types as being well-suited to the steel cage, but I could picture these two Jonathans facing off. The giant glasses take onthe slim glasses. One writes panoramic bestsellers chronicling America; the other pokes and prods at his words for literary and visual effect. They’ve both been criticized for being overly sentimental, even in stories about typefaces. I think Franzen would be in better shape to fight, but they’d probably just sit, look at each other, and breathe world-weary sighs at an audience that would rather pay to see them manhandle each other than create vivid, complex characters mirroring our lives. I predict a mutual forfeit and at least one thrown cup of pinot grigio.

5. Tolstoy v. Dostoyevsky

Ladbrokes would go insane with this one. The Millions has already asked eight experts to weigh in. The two authors boast doorstops—The Brothers Karamazov, War and Peace—that blew away any other competition. The strange thing is, despite living at the same time, they were only in the same building once, and Dostoyevsky regretted that they never met. So who would win? From the pictures, neither of them seems to have been a hale and hearty fellow, although Tolstoy's military career might give him a slight leg up. Both have impressive beards. I could see them deciding to form a tag team, or perhaps signing up with the underrated Bolsheviks.

image: bythatyoumean.com

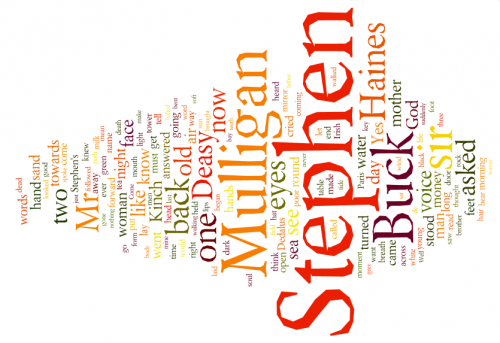

Now that James Joyce's literary corpus is finally in the public doman, I've decided to appropriate it in a singularly 21st-century manner: by readingUlysses chapter by chapter in Wordle, which creates cloud-like infographics based on how often individual words recur in a given text. Visual concordances, more or less.

Each chapter of Ulysses is remarkably different—scholars have noted that chapter breaks serve to shift from one style to another, rather than from one pivotal moment to the next—so I loaded each one into Wordle, let it remove the most common and pedestrian words, and screen-grabbed the results. Here are a few stray observations on the first three chapters, in which Stephen Daedalus's world is fleshed out before Leopold Bloom's arrival.

Chapter 1: Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus (nicknamed Kinch) is talking to his roommate Buck Mulligan in the Martello tower they're both sharing. "God" is mentioned just as often as "mother." The sea and water crop up plenty; the tower is out by the shore, after all. "Mirror" is another popular one, starting with the first line: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." But it's surprisingly renamed in one of Stephen's most famous aphorisms: "It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked looking-glass of a servant."

Chapter 2: Nestor

I've rearranged the words here to keep "Stephen" separate from everything else, since this chapter focuses on Stephen's job teaching, as well as his uncomfortable relationship with the elder Mr. Deasy. There is a great deal of authority and deference in the classroom and in the office: "yes," "sir," and the verbal conjugations of asking and knowing and crying and answering. The word "history" is hidden but memorable here, just as important as books and, ironically, even more recurrent than God: "For them too history was a tale like any other too often heard"; "All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God"; (best of all) "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Chapter 3: Proteus

Stephen's name is all but swallowed up in this chapter, which ditches its protagonist for the "ineluctable modality of the visible." Instead of names, there are his eyes and the sand, everything to see beneath his feet and behind his back. Of all the German words, "nebeneinander" (n:coexistence; adj: in parallel) is the only one frequent enough to appear here. "God" is again recurrent, but not nearly as much as "Paris" or "woman." Everything here boils down to immediate perception and thought, from the concrete elements of the sea and the shore to the clearly abstract mental verbalizations of that which is ineluctable.

I've already read Ulysses once, in an eight-day marathon as a bet with my friends, and while I enjoyed the shifts in perspective the first time around, I wouldn't have thought that the words would mark it out so clearly. I also hadn't thought about Ulysses in religious terms, so seeing the relative prominence of the word "God" in each chapter tells a story I hadn't noticed before.

Cool stuff. If nothing else, with word-clusters like "God Like Mother," "Look Back Sargent," "Eyes Going Kiss," this thing's a band-name factory.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©