I first came across Enrique Vila-Matas, whose book Dublinesque drops stateside today, on a cold snowy morning in the Midwest. School was canceled. Work was canceled. And at the top of my pile of books to read wasn't something by Enrique Vila-Matas. Instead, it was a gorgeous Melville House edition of Bartleby the Scrivener.

My back to the frozen world outside, I paged through the story of a man himself frozen in repeating a perpetual, unalterable phrase: “I would prefer not to.” The idea of a man who had moved beyond logic and reason made me shiver in the heat of the fireplace.

What could I read after a such a chillingly final story? I looked down the pile, and my eyes lit on an unlikely title: Bartleby & Co. As far as I could tell, this was the story of a man who had decided to investigate the "writers of the No." Less a novel and more a disembodied set of footnotes, Bartleby & Co. trawls across the literary landscape of figures who, like Bartleby, have gone silent. I read the narrator's skewed commentary on Salinger, and also on Alfau, Derain, Rimbaud, Celan...

So this was who you could read after being overwhelmed by the morass of Modernity, I thought. I looked at the spine. Enrique Vila-Matas. This was the author who found something new and interesting to say about these fragments we have shored against our ruins. How had none of my friends told me about this wildly popular Spanish author, churning out new books about literary sicknesses? (I couldn't even remember how that book had gotten in my room.) I ordered Montano’s Malady immediately, and then waited eagerly for the English translation of Dublinesque.

Dublinesque doesn’t disappoint. In it, publisher Samuel Riba—“he likes to see himself as the last publisher,” Vila-Matas writes—sets out for Dublin to orchestrate a funeral for the printed book, for great authors and the entire “Gutenberg galaxy.” Literature has no plans to die, of course, so the trip becomes a rather complicated affair.

The story takes place chiefly in Dublin and under the aegis of Joyce’sUlysses, but it’s no surprise when John Huston’s interpretation of “The Dead” is mentioned, or when a man strongly resembling Samuel Beckett appears. Still, the author reminds us that Riba “also took up publishing because he’s always been an impassioned reader.” And as Riba is a recovering alcoholic, it may well be that literature is a different sort of addiction for him. If this hall of mirrors, in which every book Riba (or, for that matter, Vila-Matas) has read is reflected back at the reader, seems overwhelming at first, how much more alluring it must seem to the seasoned reader, who will immediately catch the reference to Paddy Dignam or El Jabato.

No book exists in a vacuum, but Vila-Matas’s books are exceptional in their dependence on all other great books to validate their own existence. For people who (like me) don't have doctoral degrees in the humanities, it's a relief to know that there's a rather enjoyable storyline, and a great deal of wit to boot. Still, I can’t imagine anybody liking Dublinesque without having already read Ulysses and most everything else in the Modernist canon—but after Ulysses, Vila-Matas’s Dublinesque seems like one of the few twenty-first-century books worth reading.

image credit: ndbooks.com

Apparently, Colm Toibin's book New Ways to Kill Your Mother, published by Scribner this month, doesn’t provide any instruction on how to actually kill your mother. While this might be a grave disappointment to some, I’m inclined to smirk (with both glee and a bit of friendly mockery) at Toibin’s recommendation to put mom on ice—at least in fiction. Dwight Garner, reviewing the book for the NYTimes, explains: “His essential point, driven home in an essay about all the motherless heroes and heroines in the novels of Henry James and Jane Austen, is that ‘mothers get in the way of fiction; they take up the space that is better filled by indecision, by hope, by the slow growth of a personality.’”

Really, aren’t fiction mothers just a pain in the ass? If a novel has a mother in it, she’s usually too complicated and infuriating to develop in a half-assed way, and so the whole book ends up being about her. She’d just love that, wouldn’t she?

If you're a writer, you’re stuck having to acrobat around a reader’s wondering, “Where is the character’s mother? Does she know what her son’s doing?” every time you want a character to do something bad. Raskolnikov was gonna kill that landlady but then his mom came home. Groan. Guess he’ll never be friends with that prostitute.

Toibin points out that orphans are great characters in fiction, and really, how could they not be? Without all of that guidance, nourishment and guilt-mongering, orphans are free to find their own way in a world devoid of preconceived notions. Plus, devastation and an incurable longing are great ways to secure a far-reaching and easy sympathy from readers. Oh, the poor dear, that’s why this character’s acting up.

Still, I find this proposition of parentless fiction a little weird. Possibly indicative of a handful of bizarre psychological ramifications. Do we have a hard time imagining mothers without pillows clutched in their fists, coming to snuff us out? Do we really think that kids raised in two-parent households are so adjusted as to be boring? Are your parents making it hard for you to develop a personality or experience indecision and hope?

I love a little mom in my fiction. I say the more mothers, the better.

image: bbc.uk.co

Sheila Heti came from Toronto to New York this week, ready to launch her "novel from life" How Should a Person Be? in the States. I’m a fanboy, so of course I was there at the Powerhouse Arena on Tuesday night.

Two weeks ago, I had pushed a copy of the book into my friend’s hands. “You’ll get a kick out of it,” I insisted. A week later, she told me she had a clear picture of the characters: she was positive that the narrator, also named Sheila, was a tall woman with flowing, curly hair—the kind of woman who effortlessly pulls off a feather boa. And Margaux, her best friend (also the book's dedicatee), had to be blonde, with a clean-cut face and an understated, artsy style.

Well, not quite. A quick Google search led to this picture, with Margaux Williamson on the left, and Sheila Heti on the right. Sheila had put a version of herself in How Should a Person Be?, but it wasn’t quite the same as the woman who stood in front of us Tuesday night.

“Yeah, I sort of forgot to describe myself,” she said when we mentioned the discrepancy. Then she looked down and signed my book.

Did it bother her?

“No, I’m not the person I put in the book. That was a different time.”

Hmm. Would Margaux be upset if we asked her to sign the book? (Margaux has not always been the nicest friend.)

“Margaux? She’d love it!”

We went over to Margaux, who was surrounded by an adoring crowd. We opened our books to the dedication page and handed them over. She couldn’t stop smiling as she scribbled our names and her signature.

We couldn’t believe ourselves. It was like seeing the cast of The Hills in the flesh. They were actually real? Wearing the same kind of clothes we did? And signing our books, even though they’d fought about their lives being recorded?

Cool.

••••

A couple of months ago, I’d gone to a different bookstore to see John D’Agata and Jim Fingal talk about their own relationship, recorded in The Lifespan of a Fact. These were two men who had argued over most of the facts in an essay that was later turned into the book About a Mountain.

“Wow, Jim, your penis must be so much bigger than mine,” John D’Agata spouts off sarcastically in one part of the book. “Your job is to fact-check me, Jim, not my subjects.”

As it turns out, quite a bit of this dialogue had been made up. This knowledge didn’t endear me to the idea of meeting a self-absorbed artiste (D’Agata) and a battle-scarred fact-checker (Fingal). These were the characters they’d made out of themselves, after all.

Then the two men walked to the front of the room.

John D’Agata is actually extremely nice, even apologetic—one minute ofthis video shows how transparent his emotions are. I was astonished at the vehemence of my fellow audience members. “Can’t you understand that you shouldn’t present distorted facts as journalism?” they asked.

No, John D’Agata explained in an apologetic way, he wasn’t writing journalism. An essay was a completely different thing.

He seemed surprised at the monstrous caricature he’d created of himself. Jim Fingal found the whole setup rather amusing. I looked around nervously for tomatoes about to be thrown. These two writers had become victims of their own inventions.

••••

Did either pair of authors owe it to their readers to present an accurate picture of themselves? What transformation was permissible in art, if these books were supposed to be “nonfiction” or “a novel from life”? Was I right or wrong to be surprised by the people behind the characters?

I had read about these characters, but seeing the authors left me wondering: How should a person be?

image credits: velvetroper.com; torontoist.com

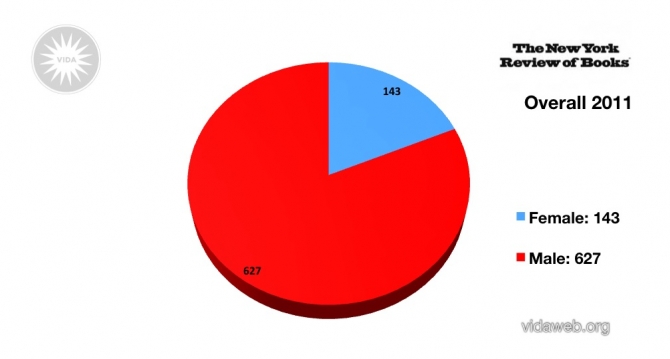

The statistics are in! Thanks to the VIDA Count, there's fresh proof that we live in a world of crappy exclusion in the books department. While I was happy to come across an article in the Irish Times about a retired High Court judge urging lawyers and judges to read great works of literature, I was made profoundly less happy by recent reports on gender and racial bias in publishing. And then I figured it all out: what the judge and the reports suggest to me is a need for empathy, and a need for more people to desire an experience of empathy.

The judge, Bryan McMahon, said that "[l]awyers should be acquainted with great literature and should learn from it. It deals with envy, jealousy, greed, love, mercy, power politics, justice, social order, punishment ... Judging also involves the soft side of the brain, dealing with compassion, understanding, imagining the extent of one’s decision.” Literature has the capacity to peel us away from the world we think we know and take us into an entirely new experience with a changed perspective. This is useful not just as an escape or to serve as some kind of refreshment; books complicate and deepen our understanding of the human experience.

So what happens when almost all of the books that are promoted and discussed in major outlets derive from a largely homogenous pool? Does this limit our access to the great variety of human experience? Could this mean—because of stuff like profitability and basic self-interest—that publishers and reviewers mostly promote the human experience that reflects theirs?

I don’t wish to come off as a big poopy diaper, but in light of the statistics showing that high-visibility literature is mostly male and most definitely white, I think it’s valuable to note that publishing is often a gross machine and often doesn’t reflect very good taste or wise choices. But as much as the nasty, naughty publishing machine is a total idiot with no gumption or integrity, I’d also like to suggest that there could be a fair amount of readers (yeah, the white ones with the money) that don’t much like that which is unfamiliar to them. Readers can just as guiltily say that they want to read a book “they can relate to.” Somehow fifteen dollars has become too precious an amount to spend on something so unnecessary as literature, but 99 cents to download some "guaranteed" blockbuster is a great modern thing.

Think of how the majority of book buyers find books these days. Amazon tells you what other people liked based on what you like. How could this possibly lead to a diverse reading experience?

To top it off, the attachment to indulgence and self-interest is rampant to the point of perversion in this country. I don’t have all my statistics in on this, but I’m fairly certain. And when the self is held as the utmost importance, how could anything of quality be read at all? Does no one want to take a risk or try something new? Maybe readers would enjoy different books if publishers and reviewers spent a little more time pushing different good books and not just the guaranteed sellers for an already established (and at this point, hopefully bored) audience.

image: vidaweb.org

I.

I got lost trying to find Washington Square Park. I can’t count how many times I’ve walked under that white arch, but this time, when I got off the subway, I circled the area for an hour before spotting it.

How did I get lost? I’m not sure if it was the unfamiliar origin, or if maybe it was the rows of summer-green trees exploding throughout the Village. We shaded our eyes against the sun, and somehow I couldn’t find a single familiar thing. I wondered if we were still in New York.

But there was something strangely beautiful in being lost. Every new street looked more real; as I rounded each corner, I slowly built up a mental map from the world around me.

II.

“I am quick to disappear when I walk; my thoughts wander until they cease to seem to be my thoughts, until, mercifully, I cease to think of myself primarily as myself for a few moments.” I read this in a stunning Harvard Book Review essay. The writer goes on to wonder “why I’m so tempted to read the world around me when I walk — especially since I would be so much better served by just paying attention to where I was going and how I was getting there.”

We make our lives out of what we see. Anything we do not see shapes our lives by its absence.

III.

Before I moved to New York once and for all, I read Teju Cole’s Open City. I had been to New York many, many times and did not think of it as a city in which one lost oneself. But every space has its crevices: Teju Cole’s narrator finds himself locked on a fire escape, looking down an unlit side of Carnegie Hall. After his despair passes, he looks up, “and much to my surprise, there were stars. Stars! ... the sky was like a roof shot through with light, and heaven itself shimmered. Wonderful stars, a distant cloud of fireflies: but I felt in my body what my eyes could not grasp, which was that their true nature was the persisting visual echo of something that was already in the past.”

When I moved to New York, it was through an airport; I did not arrive at Grand Central Station, which had always been my port of arrival. But then I took a train out, and as I crossed the main concourse, I looked up for the first time in four years. Above me was a sea-green heaven, with golden constellations dotting the ceiling. I forgot the station momentarily, mesmerized by that slice of the sky.

Do we let ourselves get lost to see what we have forgotten, to witness and retain what we have refused to let ourselves see before?

IV.

I once tried to escape the Midwest by reading Dead Europe. The book, by Australian author Christos Tsiolkas, took three weeks to make its way from the Antipodes to America. And then I read about a photographer who, trying to dig into the wreckage of his family’s and his own past, travels from Australia to Greece and then across Europe.

In Paris, he is taken to the city tourists never see: “a harsh place, a tough, crumbling, decaying, stinking, dirty city ... But the act of adjusting the camera lens, the act of focusing on an image, seemed to alleviate my anxiety.” Photography is only another form of looking, of mapping the things that otherwise would remain terra incognita.

V.

Of course I found the park, but by that time I didn’t particularly want to be there. I had been looking for something else all along, I suppose. So I unfurled the map in my head and followed it away.

image credit: flickr.com/photos/deepersea

Both The Guardian and the NYDailyNews recently posted articles about a new study that seems to suggest that modern writers are becoming less and less influenced by past literature. In trying to come to grips with the terms of the study itself – ‘influence’ was measured by non-content word usage, measuring style not content, the sampling was of books available on Project Gutenberg that were published between 1550 and 1952 (which were then all written in English?) – I’ve come to a few of my own conclusions.

Conclusion #1 There are more people who know how to read and write now. Or, I should more accurately say, more people knew how to read and write in 1952 than there were people who knew how to read and write in 1920, let alone 1870, or 1660, etc.

Conclusion #2 More books became more available as more people had more time and money to read them. There were also an increasing number of people writing who weren’t rich white males, though I bet it was still pretty difficult in 1952 to get published if you were not male or not white.

Conclusion #3 Just because I have a shitty attitude about widespread generalizations based on out-dated source material quantified in meaningless ways doesn’t mean we shouldn’t get very upset and all up in arms about society crumbling because we’re all not reading the classics.

Conclusion #4 All of the people I’ve known who studied the Classics – as in Greek and Latin Classics – were incredibly dark and fatalistic. They were the smartest people I knew but by and large the most dangerously depressive.

Conclusion #5 Dead authors I’ve personally been heavily influenced by: Dostoevsky, Sherwood Anderson, Chekov, Raymond Carver, John Updike, Nabokov, Hemingway, Faulkner. Dead authors I could write like without coming off as a complete and total ass: 0.

Conclusion #6 Meow meow meow meow, meow meow meow.

Image: sodahead.com

Craig Mod sings a funeral dirge for book covers, yet another beautiful casualty of the shift toward digital distribution of “books.” Because they have lost their purpose, covers must die: as bookstores finally succumb to the efficiencies of Internet distribution, book covers themselves will lose the emphasis they currently have in the publishing world. Instead, clever designers will continually tweak covers—or app icons?—to leverage the characteristics of whichever particular method of distribution—Kindle, Apple Store, whatever—to their favor. Or so it would seem.

I wonder about this. I'm not so sure that major publishers will be keen to give up the "branding" achieved by iconic cover design. While Mod is definitely correct that the cover image at an Amazon book page doesn’t dominate your impression the way physical covers do when you approach a table display, I think he trivializes its importance. When you search for a book, there is the momentary, all important recognition of a particular cover: I want this edition; I recognize that book. And I bet, as was shown with comprehension and retention of hypertext compared to linear text, that the much vaunted “data” presented to customers on a typical Amazon book page rarely enters memory or affects cognition or purchasing behavior—at least, not as much as the initial impression of recognizing the book’s cover does. Certainly someone at Amazon has metrics on that. [See note on metrics below.]

It is this snap of recognition that makes bestsellers. The industry knows this. Hence, the dextrous marketeers have worked to craft immediately recognizable bestsellers through standardizing distribution channels, optimizing displays, and studying consumers perceptual habits. Marketing departments will want to continue to have control over of each book’s brand, hoping to win the lottery by hitting on the next Fifty Shades of Grey,Harry Potter, Twilight, etc. Covers will still get the most design attention, even if their function and role are in transition for some time.

Still, many of the observations Mod makes about the ghostly controls on electronic books are apt. For instance, the Kindle opens directly to the first page of text—I wonder if publishers make this choice or if it is an aspect of the product they’ve ceded to end retailers, along with price—tucking away the front matter and indicating that the information it contains is of little use to the usual reader. Who knows how to decipher that Library of Congress info, anyway?

Anyway, covers. We may mourn them. They’re doomed because they’re not essential to the non-object ebook. Virtual guts need no physical protection as they’re removed from a virtual shelf and “opened.” And it’s hard to see how methods of preventing remote deletion or emendation of your library would be integrated aesthetically into overall book design.

But fear not. You can still sticker your device.

[Note on metrics: There’s a difficulty in leveraging them as efficiently as possible. Publishers may well be interested doing so through the perpetual refinement of "customer experience" through things like A/B testing. Because of the constant accrual of data about customer behavior that is harvested, there is enormous potential to positively encourage sales. By having two versions of a cover and tracking if either seriously outperforms the other a retail site, marketing teams could, hypothetically, select the cover that performed better and make it, thereafter, the official cover for the book. Problem is, I doubt that Amazon or the other end retailers of ebooks would be enthusiastic about freely sharing the info they gather on customers. So there’d be less integration of data into decisions about which cover did best where. And I doubt publishers will be eager to cede ultimate control over their covers to Amazon, et al. Of course, this isn’t a problem for Amazon’s publishing wing. Then there’s the insidious side of A/B testing. It happens so fast now that marketeers rarely take the time to think about the why B outdoes A in this instance. This is because, essentially, why don't matter. Final causes aren’t as important as immediate effects—namely, money for the company—and so don’t need to be investigated. The danger of this is that marketeers tend lose sight of the fact that they have an impact on the results: you put meat and potatoes in front of a hungry person, they're going to eat it.]

Image: etsy user ilovedoodle

Ben Marcus, writing in the New Statesman, proposes the idea that the new fascination with apocalyptic fiction is partially in response to a need to raise the stakes of American drama after 9/11. Apocalyptic fiction is a playground realist writers can now traipse through because such fears and expectations are no longer considered mere fantasy. Marcus writes: “Nothing of the 9/11 attacks even remotely suggested an apocalypse but they certainly helped expose the troubling fiction of our immortality. Which might mean that fictions of our end times are now, through bad luck or comeuppance, however you wish to view it, among the truest and most realistic stories that we can tell.”

To begin with a small, but important, clarification: I do not intend here to suggest how or what novelists should write about. Novelists are under no obligation to anyone for how or what they write. I am interested only in examining further Marcus’ observation of the historical and psychological conditions in America post 9/11 that some novelists and readers might be responding to. I agree with Marcus when he says “If this is a new development, it is worth considering why the end of the world is poised to join the suburbs and bad marriages as a distinctly American literary fascination.”

A question that comes up for me is to what degree end times fiction is a reconciliation with the present (coming to terms with what American life is now), and to what degree it foretells our larger attitudes about the future. If we’re willing to consider the notion that some psychological need is being fulfilled – at least tapped – through literary means, I think it’s interesting to look at the difference between this new end times phenomenon and Cold War paranoia. In the Cold War, dropping the atom bomb always remained a threat. After the Cold War was over, school children huddling beneath their desks and families cowering underground in bomb shelters seemed like an overreaction. We most definitely understood the terms of the engagement during the Cold War – we knew the nature of the conflict and could identify the enemy. Even if the Commie was infiltrating your neighborhood, there was still a very clear sense of that Commie’s motivation. Then think of Orwell, Huxley, Bradbury (not all American writers but surely read widely by Americans) warning us of what society might become if we’re not careful. Those writers were responding to the changes and possibilities that were apparent in their time, all focused on the implications of larger societal structures and all very much imbedded with a sense of democratic responsibility.

In the decade leading up to 9/11 major events were the very swift Gulf War, Rodney King and the LA Riots, Bill Clinton spilling on a dress. America was not living in fear – uncertain or otherwise – at the time. The 1990s top seller lists were riddled with Steven King, Michael Crichton, and Tom Clancy. Regardless of where ‘serious’ lies on their list of priorities, King, Crichton and Clancy were all writing to thrill. This new insurgence of serious, literary writers tackling end times is likely due to the observation that we are more willing to take such things more seriously. Now, the subjects of thrillers are not solely relegated to fantasy. What is new is our sense of the reality of such fears. For the most part, the general public had no real or accurate conception of who was responsible for 9/11 or why America was attacked. The nature of this new threat remains slippery, intricate, complicated – elusively grand. We now fear everything. It’s also partly our fault, but there’s a sense that it’s too late to fix it. The new end times fiction isn’t about precaution, it’s the aftermath. These tales are post-culture, post-society.

If we don’t have a clear sense of ‘the enemy,’ we also don’t have a very clear sense of ourselves. To be American now seems to mean to be privileged, ignorant, shitty. Self-interested to a harmful degree, at every level of interaction. The freedom we hold dear to be the freedom to make and spend money. America contains much more than that but American identity is now so often talked about in such imprecise ways by people trying to sell something that it’s hard for someone not trying to sell something to join the conversation. Or at least be heard among all the noise. Marcus points out that the American suburban drama can now seem indulgent, irresponsible – how smug and lucky we are to pout over our incredibly safe, decadent, awesome lives: “To call the novel irrelevant because it couldn’t top 9/11 – that seemed strange, a botched diagnosis. But it did not prevent a shame from settling over writers who favoured domestic literary subject matter that could very well be deemed minor.” No serious, deep consideration of any subject should be considered minor, but there is now a compulsion to raise the stakes. I think it’s quite valuable to consider the new end times fiction as being a response to that. The levels of perceived and potential devastation have been turned up a notch or two.

I think it should also be noted that much of the current end times fiction is still largely domestic: in Marcus’ The Flame Alphabet and McCarthy’s The Road the protagonists are both fathers whose concerns are still centered on family. Family is, after all, what we have left (hopefully) once every other structure has collapsed. And American fiction does have a quite excellent tradition of rugged individualists. The drama of the end times is no doubt reassuring in that most end times stories are to a great extent survival stories. Even if everyone dies at the end they do so heroically – they have proven great spirit, valor, and humanity in their fight and thereby given meaning to their existence. These stories are in some way telling us that we can indeed persevere – even after it’s all gone to shit – and do so with something like integrity. Or, if not integrity, we will at least learn something valuable about ourselves.

I have no doubt that apocalypse fiction, in addition to vampires and werewolves, will be around for quite a long time, but I also sense end times fiction will lose its newly celebrated appeal. Literary fiction isn’t often that popular – and I think the perceived ‘anomaly’ of serious fiction taking on genre characteristics actually helped literary fiction writers get more attention – and the American imagination, for writers and readers both, demands reinvention quite often. My question then is: what comes next? Will novelists continue to feel the need for high drama? Can we stop quibbling over the distinctions between high and low subject matter? What will now be the course of American fiction?

image: www.ep.tc

The Nation has devoted a substantial chunk of their new issue, including a post-apocalyptically gloomy cover, to the subject of the most revered and loathed retail behemoth on the planet. The issue, "Amazon and the Conquest of Publishing," offers three long essays on Jeff Bezos's company's origins, controversial labor practices, tax-evasion efforts, data mining tactics, and its conflict-of-interest-y slouching towards publishing its own titles. (Sidebar: Amazon quietly bought Avalon Books, an imprint specializing in romances and mysteries, this week.)

The best and most comprehensive of the essays is Steve Wasserman's "The Amazon Effect." Wasserman, a former editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review (which folded its print edition in 2008), paints a startlingly dystopian picture of Amazon as a company which, like its social networking counterparts, seems to harbor a sinister messianic ambition for itself, a desire to braid itself into our neural pathways.

From street level, they seem to be succeeding. Amazon has always seemed to me less a company than an idea. As Wasserman notes, it has no physical space (at least none that it pays fair taxes on). No one walks into an Amazon store; there are no Amazon greeters. And news that the company would like to replace its human workers, ostensibly the ones who saran-wrap your paperbacks to pieces of cardboard, with robots, hardly surprises, even if it is speeding us towards a vision of the future that would have made Aldous Huxley give us a withering look.

And it seems as though Amazon is banking on the fact that, like it's social network counterparts, it has become an idea, an ingrained feeling, a Pavlovian reflex—a verb. "To Amazon," in my working definition, might refer to "the immediate silent flush of gratification felt upon purchasing a dozen books one has been meaning to read with only a few clicks of a mouse, some of the books hard-to-find novels at scandalous mark-downs."

My sensitive information is saved on the site; I click hectically through to checkout, not the least bit anxious that Amazon has this information, maybe even a bit annoyed to be reminded it does, because a kind of anticipatory saliva has already started accumulating in a part of my brain I didn't know existed before Amazon. Finally, the words "free shipping" mitigate any subsequent feelings of buyer's remorse I might feel as the confirmation emails start cluttering my inbox. My wallet has not moved from my pocket. I have not moved from my chair. Twelve books are on their way to me, and nevermind that it might realistically take me several years to finish them all (in between reading the other stacks of books I ordered last month, and the month before, etc.). The shipping was free. I win.

Understandably, Amazon has its evangelizers, people like Slate's Farhad Manjoo, who argued several months ago that Amazon is "the only thing saving" literary culture, because the company has increased the number of books people buy, which (fishily) leads Manjoo to wish death on public spaces that encourage the buying of said books, a.k.a. independent bookstores. (This seems especially fishy given that said journalist writes for said website which, he admits, is in business with said online retailing behemoth.)

You might recall that this is the same article in which novelist Richard Russo is taken to task for a New York Times op-ed in which he pleaded the case for independent bookstores, the same Richard Russo who spoke at BEA this week, urging publishers to "find a spine" against the Amazonian bully.

But Manjoo is right: Amazon is, in many ways, the ideal friend and accomplice to young literary persons of the Great Recession era. The company appeals seductively to our general poverty, agoraphobia, sense of entitlement, and desire for immediate gratification. And with e-books, which, unlike toaster ovens, can be downloaded to your Amazon Kindle™ instantaneously (in a proprietary format locked to other e-readers), you don't even have to get up and run an illegible squiggle representing your signature™ across the UPS™ guy's Delivery Information Acquisition Device (DIAD)™.

A number of us who return again and again to Amazon aren't even lazy or agoraphobic; we're just broke. We go to our independent bookstores to browse and read on the big "poofy" (Manjoo) couches, buy a coffee, engage the sales attendants in English major banter: a combination of activities which we like to think of as "showing our support." And then we go home and buy a dozen books in a few clicks from the enemy.

What to do, Independent Bookstore, when my heart is your husband, but, as Bezos knows, my wallet's a slut?

Bookstores seem to be thriving in Tokyo. I can't walk two blocks in any direction without seeing the cheery character for book, “本”. Those searching for the rare vintage edition or secondhand paperback get their fix in Jimbochō. This neighborhood lines one broad avenue (plus myriad side streets and back alleys) with tons of used-book shops. And as this is Japan, it's all about specialization, with paperback “general stores” outnumbered by closet-sized nooks crammed with French classics, music magazines, and hairspray-heavy '80s porn.

Kanda Kosho Center (named both for the Chiyoda Ward district and for the literal translation of used books, kosho) is Jimbochō's used-book gateway, nine floors of categorized havens kitty-corner from the train station. The handy placard posted adjacent to Kanda Kosho's lifts is of no use if you don't read Japanese, but no worries: poke your head into a shop, and even the skeeziest porn joint's owner won't give you a passing glance.

Want a three-volume set of The Fishes of the Japanese Archipelago, back-issues of Japanese-language rugby magazines (who knew??), or a monthly periodical pointedly titled Gun? Those can be had on the third and fourth floors, respectively. Miwa, the all-kids bookstore on 5, features Golden Books from an alternative universe, like “Oden-kun”, whose titular hero is an anamorphic daikon radish. Beyond the wonderful jazz and classical record shop crowning Kanda Kosho, the upper floors all house unrelated porn shops, their otherwise muted environs punctuated by the sharp crackle of individually-sealed plastic wrappers, as customers dutifully pull out and shove back periodicals like Cream and Scholar from overstuffed shelves.

Let's say you didn't find that specific skin-mag you so desired. You're totally in luck! A brief jaunt off Jimbochō's mainstream is Aratama Total Visual Shop (the “visual”, written in English, is a clue they sell lots of nude stuff) and its mirror-façaded, younger kindred. The latter is stocked almost entirely with bondage and fetish magazines, which surprised even this intrepid reporter in their diversity. Aratama the elder contains an encyclopedic array of AV photo-books and PG-13 gravure mags, but its achievement is a whole room of posters and life-sized cardboard cutouts of cuties. The addition of sealed, autographed photographs of various models (going for like $150-400 per 4x6” print) feels almost superfluous.

I can spend hours in Shinjuku East's Kinokuniya, the ferroconcrete bookstore behemoth that makes its shiny Manhattan cousin feel absolutely puny by comparison. But for those treasured and unique—yes, sometimes very deviant—finds, Jimbochō is the only destination.

Images: courtesy the author

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©