My first bout with consumption happened in junior high. Tuberculosis has a long literary history, complete with a dedicated Wikipedia listing, but until I wrapped my pubescent mitts around Crime and Punishment, I didn't associate it with consumption. To me, TB meant Mantoux tests and subsequent Masters of the Universe action figures as reward for sitting still. But Fyodor Dostoevsky unveiled a world of impassioned and desperate players, literally “consumed” by the harsh world around them.

Below are three cherished Dostoevskian consumptives, from the physically frail to the societally suffering. Dostoevsky newbies, you'll also find some emblematic quotes to whet your appetites—all from the superior Richard Pevear/Larissa Volokhonsky translations. I've tried to keep it spoiler free.

The Idiot: Ippolit Teréntyev, ailing atheist

My favorite Dostoevsky novel features such enduring characters as the “idiot” Prince Myshkin, a kind, innocent—and widely appraised as “Christ-like”—epileptic, and the bubbly Aglaya (I always preferred her to the femme fatale Nastassya Filippovna). Add to these the iconic, flush-cheeked, suicidal consumptive Ippolit. The 18-year-old's plot-stealing aside “A Necessary Explanation!” contains some of this emotional roller-coaster's most forsaken prose:

Isn't it possible simply to eat me, without demanding that I praise that which has eaten me? Can it be that someone there will indeed be offended that I don't want to wait for two weeks? I don't believe it; and it would be much more likely to suppose that my insignificant life, the life of an atom, was simply needed for the fulfillment of some universal harmony as a whole.

The Eternal Husband: Liza Trusotsky, casualty of circumstances

I'm haunted by Liza, born of a clandestine affair between dashing Velchaninov and consumptive Natalia. Velchaninov senses Liza's suffering and tries to pry her from her abusive, cuckolded “father” Trusotsky. Liza's torn existence between Velchaninov, who truly cares for her, and Trusotsky—who, despite his cruelty, she still loves—resounds in her departure to a foster family:

“Is it true that he'll [Trusotsky] come tomorrow? Is it true?” she asked [Velchaninov] imperiously.

“It's true, it's true! I'll bring him myself; I'll get him and bring him.”

“He'll deceive me,” Liza whispered, lowering her eyes.

“Doesn't he love you, Liza?”

“No, he doesn't.”

She succumbs to fever, and though Doestoevsky never explicitly calls it consumption, the implication of wilting under the world's pressure, abandoned first by her “real” father Velchaninov and then by her booze-addled “father” Trusotsky, is deafening.

Crime and Punishment: Sonya Marmeladov, self-sacrificer

The interplay between sickly Katerina Ivanovna and stepdaughter Sonya evolves consumption beyond illness. While Katerina defies a crowd (“I'll feed mine myself now; I won't bow to anybody!”), coughing up blood before her terrified children, I feared most for Sonya. Her world threatened to “consume” her, as she prostituted to support her younger siblings. Add her unyielding devotion to Raskonikov, the impoverished student behind the novel's murder:

Stand up! Go now, this minute, stand in the crossroads, bow down, and first kiss the earth you've defiled, then bow to the whole world, on all four sides, and say aloud to everyone: 'I have killed!' Then God will send you life again. Will you go?

And...she doesn't break. Altruistic Sonya follows the condemned man to Siberia.

This is why I am hooked on Dostoevsky: for conjuring such compelling “consumptives." Though I may not relate to their hardships like I do Haruki Murakami's everyman boku, it's thanks to Dostoevsky's fully-realized creations that I want to know them. Raskolnikov says it best:

Suffering and pain are always obligatory for a broad consciousness and a deep heart. Truly great men, I think, must feel great sorrow in this world.

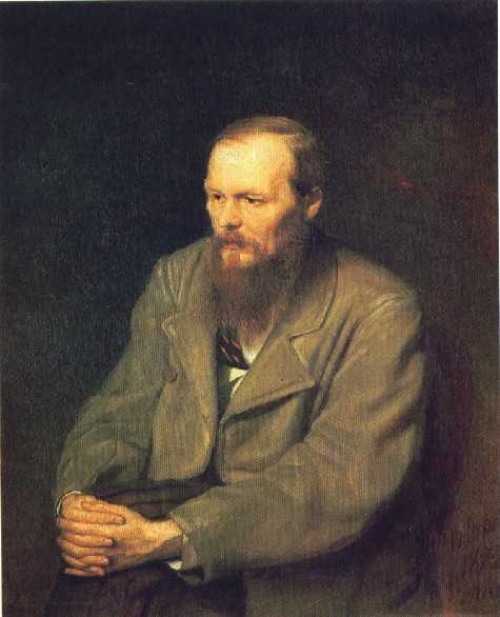

Image: Vassily Petrov's Portrait of F. M. Dostoevsky via Rhode Island School of Design

Desmond Pepperdine has a secret — one that’s revealed on the first page of Martin Amis’s new novel, Lionel Asbo. The secret itself is pretty unthinkable, but it precipitates a crime so unthinkable that, once it’s happened, Desmond can’t think about it. All of which got me thinking about the secrets that run riot though Amis's whole oeuvre. Here's my Top 5.

Read More

Stephen King, horror's überscribe, is still setting the pace with new novels. If 2013's print-only Joyland doesn't get you going, check this: a recent Los Angeles Times article details Doctor Sleep, a sequel to The Shining penned 35 years after the original. Doctor Sleep focuses on a now-adult Danny Torrance, the child with “the shining,” drawing intriguing parallels to youngShining-era readers who are now adults themselves. But the article's final paragraph bears the most divisive news: Hollywood is also talking about a prequel.

NO. No, no, no. Look, some doors do not need to be opened. Where's Hallorann when we need him, warning Danny (or us, or the filmmakers):“You ain't got no business goin' in there anyway. So stay out.” Take my hand through this Shining survey, from the late 70s original to futures unknown.

1977, Stephen King's novel horror: King's first hardcover bestseller is terrifying to this day, a modern haunted house tale enveloping a semi-autobiographical core: the tormented, alcoholic writer terrorizing his own family.

The good: Father Jack Torrance wields a sadistic roque mallet: “Roque...it was a schizo sort of game at that. The mallet expressed that perfectly. A soft end and a hard end. A game of finesse and aim, and a game of raw, bludgeoning power.” The bad: no "all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" (typed by Jack, perhaps in subconscious homage to Christopher Knowles). The ugly: Danny's skin-crawling encounter with the old hag: “Still grinning, her huge marble eyes fixed on him, she was sitting up. Her dead palms made squittering noises on the porcelain. Her breasts swayed like ancient cracked punching bags. There was the minute sound of breaking ice shards.”

1980, Stanley Kubrick's film: It's rare that a film stands so vividly over its source material, but Kubrick's Shining does. His Overlook is my Overlook.

The good: Kubrick transformed the Overlook Hotel into a practically living, breathing entity, a frightening, temporal maze of impossible passageways, sometimes containing Grady's twin daughters (also absent from King's novel), intoning: “Come and play with us, Danny. Forever...and ever...and ever." The bad: not a damn thing. The ugly: the old hag, or rather, the young woman who seduces Jack and turns into the old hag.

1997, Re-adaptation as TV miniseries: King's major disappointment in Kubrick's adaptation was casting wild-eyed Jack Nicholson, as King preferred a more believable everyman for the role of Jack Torrance. Hence King's screenplay for an ABC miniseries, arriving nearly two decades later.

The good: As in King's novel, Hallorann survives the horror, and it's Danny who discovers the old hag. The bad: the Stanley Hotel location, while true to King's writing, lacks the labyrinthine dread of Kubrick's environs. (And don't get me started on the soap-worthy acting.) The ugly: those hedge animals, wisely absent from Kubrick's film, proved scarier in print than on screen. ABC gave King's verbose IT similar treatment in 1990 (without King's screenwriting credit), traumatizing coulrophobes everywhere and proving that living topiaries are no Pennywise the Dancing Clown. Did you even know there was a Shining miniseries?

2013, Doctor Sleep, a three-decades-hence sequel: I got into King as a preteen, probably around the same age as younger Shining readers, tackling Desperation (disgusting) and Bag of Bones (heart-wrenching) in the late 90s. It's notable, and unfortunate, that both became avoidable TV movies. I approach Doctor Sleep guardedly.

The good: We'll know in wintery January if Doctor Sleep is crud or an early classic. The bad: King's preview of Doctor Sleep at the 2012 Savannah Book Festival, featuring a still-young Danny revisited by the old hag, closely mirrors The Shining in disgusting descriptives. The ugly: Evidently, adult Danny will be fighting quasi-vampiric immortals.

201?, The Shining filmic prequel: I don't need Danny's “shining” ability to foresee this as a very bad idea.

The good(?): Screenwriter Laeta Kalogridis (who penned claustrophobic Shutter Island) is involved. The bad: I fear this “Outlook origin story” becomes a near shot-for-shot remake like The (2011) Thing and/or casts Ryan Reynolds or Channing Tatum as the Outlook's caretaker. The ugly: old hag in her carefree pre-bathtub days?

If a more authentic TV miniseries couldn't shake Kubrick's masterpiece as the definitive cinematic Shining, what more could a prequel possibly afford? I hope it ends like Jack in Kubrick's film—spoilers!—lost and frozen in a (developmental) maze.

Images: Main image via The Overlook Hotel; Danny via GoneMovie.com;Here's Johnny! + Grady Twins; Pennywise + Hedge Animals; Overlook Hotel party photo via Haunted American Tours

It's fun to argue about difficult books (cf. Publishers Weekly's Top 10 and the ensuing comments); it's even fun to read one every now and then. But what about unreadable books—the ones where you can't hope to get to the end, no matter how hard you try? Remember now: we're not talking about long books or simply challenging books. I'm used to those. In college, I had to read War and Peace, down to its dual epilogues, in two weeks; I readUlysses in eight days on a bet. I'm talking outright unreadable.

Here are five books that make JR look like JWOWW.

I love Péter Nádas, but this Hungarian master pushed his first great novel to the limits of the form, and barely made any concessions to readers. Even the brilliant bookseller Sarah McNally says reading it is “like climbing a mountain.” There are two first-person narratives—the memories of a Hungarian man in a love triangle, and his alter-ego in a lightly fictionalized memoir of the first narrator’s own life—and, near the end, a third narrator who punches holes in the first two. I’m a careful reader, but I had a hell of a time figuring out who was narrating some chapters. More than anything, though, the sentences can be downright impenetrable:

“Lovers walk around wearing each other's body, and they wear and radiate into the world their common physicality, which is in no way the mathematical sum of their two bodies but something more, something different, something barely definable, both a quantity and a quality, for the two bodies contract into one but cannot be reduced to one; this quantitative surplus and qualitative uniqueness cannot be defined in terms of, say, the bodies’ mingled scents, which is only the most easily noticeable and superficial manifestation of the separate bodies' commonality that extends to all life functions..."

Okay, the PW people were right to put this on their list. Finnegans Wake(no apostrophe there!) is filled with multilingual puns from European and non-European languages. Your only hope, they suggest, is to read it out loud in your “best bad Irish accent.” I might add the suggestion to pick up Joseph Campbell’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake—then you’ll know that the looping sentence on page 75 boils down to, more or less, “As the lion in our zoo remembers the lotuses of his Nile, so it may be that the besieged [man] bedreamt him still.” There’s a dream-narrative, a long internal monologue, the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section that incorporates thousands of rivers’ names, and quite a few puzzles and tricks to make any regular reading a nearly nonsensical experience. And that's not even getting into the last sentence, which begins what the first sentence ends.

3. Maze

Now we’re getting into more concrete definitions of “unreadable.” Christopher Manson's book is narrated by a strange beast who describes you, the reader, traveling through a maze of 45 rooms, but the maze in question is actually encoded in the book itself—a room on each page spread—and it’s fiendishly difficult (chew on that, House of Leaves). With Choose Your Own Adventure, you can look through all the pages and pick the story you like best. But no matter how many times you flip through these pages, there's no way to just guess your way out of the Maze. The Internet has made this challenge a mite easier, but computers can’t solve the riddles within for you. And even when a shortest path is found through the hundreds of doors between Room 1 and Room 45, there’s another riddle encoded in the random objects within each room. Why was the maze built, though? Why are there so many clues that people once lived there, or can be heard in other rooms? What other riddles remain to be found? The book has been uploaded to the Internet, so go ahead and look.

Okay, so it probably isn’t fair to include philosophy here, but Jacques Derrida devised his writing style specifically to evade any hope of a central, compact conclusion—the premise behind his literary theory, Deconstructionism, being that there no longer exists (if ever there did) a stable organizing principle in any text or system of thought. He did a fantastic job of proving his point with his own words, which famously loop around themselves and move farther and farther away from any truly linear argument. On Grammatology is where he takes that logic to its extreme—even (like modern art writing) to the point of being nearly incomprehensible in translation:

"Let us now persist in using this opposition of nature and institution, of physis and nomos (which also means, of course, a distribution and division regulated in fact by law) which a meditation on writing should disturb although it functions everywhere as self-evident, particularly in the discourse of linguistics. We must then conclude that only the signs called natural, those that Hegel and Saussure call “symbols,” escape semiology as grammatology. But they fall a fortiori outside the field of linguistics as the region of general semiology. The thesis of the arbitrariness of the sign thus indirectly but irrevocably contests Saussure's declared proposition when he chases writing to the outer darkness of language..."

There’s unreadable, and then there’s unreadable. A manuscript from the 1500s written in a script and language that resembles no other on earth, theVoynich manuscript has stumped amateurs and professionals alike. The pages include many strange drawings, from naked women in basins with tubes to plants that do not exist in real life. The Beinecke Library, which houses the original sheets of parchment, says that every week they receive numerous emails claiming to have broken the code, “but so far no theory has held up.” Until that changes, though, the entire manuscript is available on the Internet for codebreakers everywhere to solve.

image credit: Duncan Long, http://duncanlong.com/blog

For reasons unknown to me, this story about a St. Paul man threatening a 62 year-old woman with a sword over a borrowed book has gotten way toomuch press. As a fan of St. Paul, and in the spirit of promoting the Midwest as a fairly decent place to write, I’d like to dwell on some of the story’s finer aspects.

Books matter to Midwesterners. As far as I can tell, the whole ruckus began when the suspect threw the book he had borrowed onto the floor, and the kindly loaner of the book gave him a little shit about it. Not only does the woman here acknowledge the value of books by suggesting they don’t belong on the floor, but the borrower, by his swift decision to get a weapon, suggests that he, too, knows the import involved here. If the guy didn’t think it was a big deal to throw a book on the floor, why would he bother brandishing a sword? It hard to imagine any of this happening over a Gilmore Girls DVD.

Midwesterners have Scandinavian impulses regardless of whether they are actually Scandinavian, and Scandinavians are insanely afraid of getting called out on something they did poorly. Scandinavians are also almost godlike in their ability to bring shame on others. We have here the genius of seemingly innocent Midwestern passive aggression: the woman suggested he just throw the book away if he were going to leave it on the floor. She doesn’t accuse him directly of doing something shitty but suggests that he might as well have done something shittier. Most people have likely expected the worst from him his entire life. And the poor guy, who later in jail admits he is an idiot, can’t help but get emotional: he, too, is caught up in the Scandinavian shame cycle.

And then there's his choice of weapon. A sword. Really? Most people I hang around with aren’t really prone to take an unsheathed sword as a threat. A gun? Sure. A big knife? Oh yes (more on that in a second). But a sword? From a kid who also has ninja stars and nunchucks? If it weren’t for the sword, there would be no story. Whatever the guy’s intentions, he has succeeded in provoking a great amount of curiosity. He might not be a good neighbor, or a good criminal, but he has proven that minor criminals can still surprise us, and that sometimes people’s small quirks get the most attention.

Saturday's frightening incident in Times Square lies on the opposite end of the blade-wielding spectrum. While our book borrower's actions provoked lots of trashy curiosity, the killing of Darrius Kennedy brings up a whole lot of actual fear. His standoff with the cops, the bystanders, and the rolling cameras of a hundred smartphones was not funny; it was chaotic and very sad. For all we know, both men might have begun with the same small, dumb impulse: a trigger response to a mix of panic, fear, helplessness. Our book borrower only briefly acted on the impulse. Mr. Kennedy took it to the limit.

Image: faildaily.blogspot.com

Since I came of legal drinking age, I've been bringing books to bars. I pair literature with libations at home (whisky, usually, with or without the “e”), so why not do the same at my local watering hole? Trust in some shrill Yelpers to question the practice: “Why are people sitting at bars reading books??? It's not a library...I know Bukowski is cool, but I'm sure he had no part of this kind of debauchery.” Love it or hate it, the recently opened Molasses Books in Bushwick is bringing these two hobbies/passions/addictions closer than ever, offering tipples and tomes under one roof.

Its liquor license is still in the works, but Molasses and fellow newcomer Human Relations (a short trek up Knickerbocker Ave) have advantageous locales. Bars and art pair well in Bushwick, and I think books will, too.

Now, I understand this goes against the grain of bar dynamics. Inhibitions drop as intoxication increases, people start chatting and—sometimes—stuff happens. I engage my mingle-mode at gallery openings, and I'm not totally aloof at bars, either. This is why my preferred joints for focused reading are dives.

Take the now-shuttered Mars Bar. Despite its sticky surfaces and dodgy characters, everyone kept to themselves, hunched over their spirits of choice. While Mars Bar didn't boast a wall of whiskeys, if you ordered a shot of Jack Daniels, you received an overflowing tumbler of it. Since I was going to be there awhile, I could make major progress in brick-sized books, like Neal Stephenson's historical sci-fi behemoth The Baroque Cycle.

I take a cue from Haruki Murakami's everymen (sometimes only dubbedboku, i.e. “I/me” in the masculine sense) who hemorrhage hours in bars. Often, they arrive with an armload of Kinokuniya purchases, like Tengo in1Q84 or the sleuthy narrator of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Nobody questions why they read in bars; it's just second nature. So when I meet friends for dinner in the East Village, I typically hit basement sake saloon Decibel first, ducking into the narrow bar with whatever novel I scored from St. Marks Bookshop down the block. Nursing chilled shochu, I'd study my grammar handouts from the Japan Society and, on occasion, try impressing the female barstaff with just-learned vocabulary.

This is why I avoid reading in Tokyo bars: chatting with barmates affords excellent Japanese conversation practice. Plus my abilities improve after I've had a few. My preference for ultra-tiny Golden Gai dives and immersive fetish bars sorta distract from the prose, anyway.

Lorin Stein, The Paris Review's editor, proudly brings books to bars, though his hangouts have changed after favorites faced renovations. My book-friendly biker bar Lovejoys in Austin, TX, recently tapped its final draft. Lovejoys also attracted tattooed, Bettie Page lookalikes, so I admittedly didmingle there.

While I search for my next haunt, paperback in hand, I ask you: are you a bar reader? Does a particular book entice you toward a bit of boozing? All experiences and inspirations welcome, and the first round's on me.

Image: The Gents Place

Walking into the Strand yesterday, I made my way past teetering stacks ofFifty Shades of Grey and every possible combination of the Hunger Gamesbooks. Then I stopped.

Back up: There’s a reason everybody’s reading these books, right? Should I be so quick to write them off as “junk books”? Are they any better for you than a Crunch bar?

The New York Times reviewed airplane lit at the beginning of this summer. Arther Krystal discussed “guilty reading” at The New Yorker. And although James Patterson and John Grisham are on the bestseller list, they’re jockeying with Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Jess Walter’s Beautiful Ruins. But really, why are people still reading dime-store books?

Because those authors are just as smart as the analysts at Frito-Lay.

I don’t think The Hunger Games is as brilliant or as likely to endure as The Giver or 1984, but I knew from the first sentence (“When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold”) that it was well-crafted and carefully designed to keep its readers hooked. Otherwise I wouldn’t have read all three books, in 24 hours, and felt exhausted at the end. But, just two months after reading that trilogy, I can barely remember what the Quarter Quell is. In contrast, my roommate just finished reading Dr. Zhivago and huge chunks of the book came back to me unexpectedly, even though I hadn’t thought about it in four years.

So why did I remember Yuri Zhivago better than Katniss Everdeen? Think of it this way: we barely register the experience or feeling of breathing unless we’re struggling to stay abovewater. There’s something to unpack in both commercial fiction and literary fiction, but the latter category is intentionally designed to be more complex, more mentally taxing, and consequently more memorable. It's not that literary fiction (which, let’s face it, is another genre of fiction) is inherently better or cleverer than thrillers or sci-fi—only designed to be better savored, remembered, and appreciated by critics, teachers, and analytical readers.

Which is why, even if I’m just reading for fun, I can’t shake off a feeling of, well, sloppiness or formulaic writing in popular or genre fiction. If the dime novels from a hundred years ago feel cliché, it’s because they were: the readers just mistook the cliché for the fashionable. In the same way, Lee Childs and Robert Ludlum won’t survive fifty years without becoming archaic, even if they're great pageturners now. But I read PD James and Stephen King, because they make a conscious attempt to push the boundaries of their genres; they’ve moved past the clichés to the larger concerns of our own time. The Children of Men has something important to say about how people will live on an overpopulated Earth, while The Standgoes into the marrow of living in a post-apocalyptic world.

Books, like food, don’t always fit into neat categories. “Junk food” isn’t always junk. It still provides something for your body, just not necessarily the most beneficial or long-lasting things. The critic Michael Dirda was a little more diplomatic when he said on Reddit that “Sometimes you want to climb Mt. Everest; sometimes you just want to take a stroll in the park.” If McDonald’s regulars can also like apples and even salads, then maybe the weary travelers at the airport reading A Game of Thrones can read The Once and Future King next, and then really go medieval with Beowulf.

And hey, that wouldn’t be a bad thing.

image credit: infoglobi.com

Fantasy bibliophiles and lovers of lush cinema are facing acute overstimulation via the epic-length Cloud Atlas trailer, which surfaced last week. Even attempting to translate David Mitchell's award-winning book—its interlocking stories, its sprawling landscapes—into a standalone production is crazy ambitious. But considering co-director Tom Tykwertackled the unfilmable Perfume: The Story of a Murderer and the Wachowskis wrote the solid screenplay to V for Vendetta, I think we're in for something special.

Were there a “Most Daunting and Badass Literature-to-Film Adaptations” award, I'd vote for David Cronenberg. He practically defined “body horror,” but Cronenberg balanced gore with ballsy, bookish films like Naked Lunch and J.G. Ballard's paraphilic voyage Crash. His adaptation of Don DeLillo's Cosmopolis (young multimillionaire/recovering vampire cruising across Manhattan via limo for a haircut) premiered at Cannes 2012. Should Hollywood ever consider another go at James Joyce's Ulysses, Cronenberg's the one to helm it.

The nine-plus hours of Hobbit-sized heroism igniting Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films deserve even the most elf-averse filmgoer's respect. Now that Jackson has confirmed that The Hobbit prequel will indeed grow by half, his Rings legacy usurps Scott Pilgrim vs the World's cheeky tagline: “an epic of epic epicness.”

On the flipside, there's Philip K. Dick. His sociopolitical sci-fi sired a succession of big-screen adaptations, ranging from the superlative (Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, based on Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and backed by the author) to the splashy (Paul Verhoeven'sTotal Recall, née “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”, and its unnecessary remake) to the wildly aberrant (Minority Report, The Adjustment Bureau).

Here we have the double-edged sword, for what appears compelling on page could become a cinematic shitshow. Minority Report's steroidal action obscured the original story's metaphysical elegance, and though I was stoked as a kid to see a live-action version of Masters of the Universe, Gary Goddard's goofy result epitomized '80s schlock-cinema. That Jon M. “Step Up 3D” Chu is plotting a He-Man reboot does not bode well.

Sci-fi literature is particularly rife with “unfilmable” gems. I doubt William Gibson's seminal cyberpunk classic Neuromancer will ever make it to the big screen, though Vincenzo Natali has been pursuing the project for eons. Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash—a decade younger than Neuromancer and a billion times more irreverent—is equally enticing and elusive, in its mix ofronin action, virtual reality, and cryptic archaeology. It's telling that Natali considers Snow Crash unadaptable as a commercial film.

Should Cloud Atlas' emotional takeaway not equal its gorgeous visuals, Ang Lee's adaptation of Yann Martel's fantasy-adventure quest Life of Pi will be waiting. This fall's cinematic options are looking truly sublime.

Main image via Badass Digest and Wikipedia, photo-chopped by the author; LOTR montage via LOTR Wikia; Blade Runner via Ghost Radio

Reading an interview with George Saunders in Blip magazine and a run-down of some of the best notes from Susan Sontag's diary up at Brainpickings makes for some pretty hefty writers-on-writing thoughts. Reading each separately can result in joy, inspiration, and serious reflection. But what happens when we force these two writers' thoughts together in fake conversation?

Imagine, if you will, a set not unlike Between Two Ferns. George Saunders waits patiently with his legs crossed, but instead of Susan Sontag joining him (as she obviously cannot), Zach Galifianakis comes out with a copy of Sontag's dairy. He sits, nervously eyeing the ceiling for wasps.

Zach Galifianakis as Susan Sontag: I think I am ready to learn how to write. Think with words, not with ideas ... The function of writing is to explode one’s subject—transform it into something else.

George Saunders: I think what a reader wants is genuine engagement from a writer: that is, he wants the writer to tell the truth as she sees it, and for the form of the telling to somehow be authentic to that which is being told. The reader wants the writer to be brave enough to step away from pre-digested forms or modes, as necessary, in pursuit of beauty.

ZG/SS [looking at his/her nails]: In "life," I don’t want to be reduced to my work. In "work," I don’t want to be reduced to my life. My work is too austere. My life is a brutal anecdote.

GS [frowning, then opening and closing his mouth twice before beginning to speak.]: I think truth, for artistic purposes, is that set of things that we feel deeply, or have felt deeply, but can’t quite articulate, and can’t quite “prove,” and, the direct statement of which feels deficient.

ZG/SS: Ordinary language is an accretion of lies. The language of literature must be, therefore, the language of transgression, a rupture of individual systems, a shattering of psychic oppression. The only function of literature lies in the uncovering of the self in history.

[A crow flies low overhead across the stage. Saunders ducks, covering his head with his arms. Zach/Susan simply glares at the bird's flight, makes to leave his/her chair and follow the bird, then sits down again, shaking head.]

GS [clearing his throat]: Art is ... paying hyper-attention to the things that make reality what it is, resisting reduction, trusting that the truest (and most beautiful) thing that can be said has something to do with the accretion of those small instants.

ZG/SS [with a sudden flailing of arms]: What’s wrong with direct experience? Why would one ever want to flee it, by transforming it—into a brick?

GS: So art—I think one reason we value art so highly is because it really is, and has to remain mysterious—in its intentions and procedures, everything.

ZG/SS: If only I could feel about sex as I do about writing! [ZG/SS stares at GS, breathing noisily through his/her nose. Keeps staring.] That I’m the vehicle, the medium, the instrument of some force beyond myself.

GS [clears throat]: In a larger sense, I think people write better when they’re happy. (Allowing for a broad definition of “happy.”) Maybe “feeling exultant” would be a better way of saying it.

ZG/SS: By refusing to be as unhappy as I truly am, I deprive myself of subjects. I’ve nothing to write about. Every topic burns.

[Saunders coughs and looks anxiously about the room. In doing so, he comes across a beer placed on the table between the chairs. He takes a long pull from it, guzzling, actually, nodding in a certain way while continuing to pull mightily from his beverage. He belches softly. Then swallows hard.]

GS: Writing dictums are the equivalent of replacing the tightwire with a wide plank: a lazy man’s approach. Safer, but less thrilling. There will never be a definition of beauty that helps anybody make some.

[The studio lights start to dim, but not before we catch a scathing look from ZG/SS in George's direction, and George looking about the room in search of a swift exit.]

Image: Caitlin Saunders c/o studio360.org

all quotes ruthlessly stolen from Blip Magazine (George Saunders) and Brainpickings.org

Apologies to Zach Galifianakis

The Morning News has decided to play Reading Roulette with six Russian authors, shooting a new one into the American blogosphere each month. And because I can't get enough of translation, I’ll be writing about this year's selections—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself. First off is Anna Starobinets's pungent phantasmagoria, "I'm Waiting."

It's no secret that Russia is a cold country, or that the name of their national drink is a diminutive of their word for water, voda. The burgeoning population, spread thinly from Kaliningrad to the farthest edge ofKamchatka Krai, has huddled in bars and in front of fires over the centuries, telling stories to while away the endless nights. Anna Starobinets is the latest in a long line of storytellers, but unlike so many of her forebears, she deliberately resists the mythic.

In "I'm Waiting," a modern-day narrator leaves some of her mother's soup in a saucepan until it becomes putrid, and then outright dangerous. How dangerous? Without giving too much away, the saucepan breeds a ghost. Then things get really weird.

We humans have a visceral response to mold and stench. We're evolutionarily conditioned to seek out perfect, unblemished food. If we eat something that makes us sick, just once, our bodies can exhibit aversion to it every single time thereafter. An attraction to spoilage isn't just strange; it's deeply abnormal. And a first-person story about this sort of attraction is even more revolting: I can almost imagine myself become this woman.

So why this obsession with her mother's soup? I grew up with Eastern European food from the countries circling Mother Russia. I love going toVeselka at two in the morning for pierogies, and insisting on stuffed cabbage with my friends. There's something deeply familiar about the food a mother makes.

But let's think about this a different way. My father was once a nuclear engineer. It wasn't until high school, when I learned about nuclear power in Chemistry class and read John Hersey's Hiroshima, that I realized the research in nuclear fusion my father had done was tangentially connected to the nuclear reactors' fission that, in Russia, had resulted in a scab of earth that humans can't go near for, give or take, twenty thousand years.

If mother's soup goes bad and ends up contaminating a pot, then a refrigerator, then an entire apartment, until outside forces have to come in with gas masks and chemicals to destroy it, it's a strangely appropriate metaphor for . . . well, lots of things.

A nuclear disaster from something homegrown? The idea turns my stomach.

Anna Starobinets has hit the nail on the head. She doesn't even have to delve into myth; the world we actually live in is terrifying enough.

Image: telegraph.co.uk

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©