Explosions, weapons of mankind, friendship, and above all, pants. These are the things important to Maverick Jetpants in the City of Quality, which is now available online and at awesome bookstores everywhere. Set in the urban decay of upstate New York, the novel follows a group of friends clinging to each other in the face of adulthood. Publishers Weekly calls it “the novel that's going to put Rochester on the map” and named it one of the Best Books for the Week. Anyone who's ever had their own version of Applebees and the Vomit Cruiser will see their own hometown in Maverick Jetpants.

Once a week, Black Balloon's editorial assistant Kate Gavino chooses the best Q and the best A from one of New York's literary in-store events. Here, Kate draws from Zadie Smith's reading at Greenlight Bookstore on September 28.

What made you want to write about your hometown?

Zadie Smith: What drew me back to [Hackney] is fiction. I love to think about it and write about it. Some of the changes I fought to put in the book since there's been a great deal of gentrification, which in Brooklyn you're perfectly familiar with. It's always most painful for long-term locals, and some of it I feel is justified. But some of it is also irrational. You're really angry about the cupcake shop even though what was there before was a wasteland with a dead body on it. That's the way it is. I do find myself when I'm [in Hackney] complaining a lot, which I probably shouldn't do.

To me, half my area is very homogenous. It's just the kind of thing that mainstream media doesn't complain about. For a lot of people, when your neighborhood becomes entirely white and entirely upper middle class, it is a different kind of invasion – stressful to the people who live there. Most stressful is the assumption on the part of that community that you are grateful that they come. That's the difference because most immigrants don't assume that you'd be grateful that they've appeared in masses. But that particular contingent thinks they're a great blessing to wherever they land.

Image courtesy the author

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature is set to be announced on Thursday, and you can bet there's a gambling pool around the winners. As of Monday morning, Haruki Murakami was in the lead with 2:1 odds, while Alice Munro, Péter Nádas, and the Chinese writer Mo Yan were in a dead heat for second place.

How good are the odds that Ladbrokes got the answer? I wouldn't wager too high. Last year, Murakami and Nádas were at the top of the list (as was the reclusive Australian writer Gerald Murnane), hot on the heels of recently published books, but Bob Dylan was getting pretty good money as well. Then the Swedish writer Tomas Tranströmer pulled into the fore, as did Mario Vargas Llosa the year before, so I think we can assume this year's winner won't be terribly controversial.

Which means my money's on a capital-L Literary author. Scanning down the list, I see the Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman. Really, Ladbrokes? The only people to win multiple prizes — Marie Curie, Linus Pauling, John Bardeen, and Frederick Sanger — were all in the sciences, and stayed in the sciences (even the one who won the Peace prize for anti-nuclear activism). Don't get me wrong. Thinking, Fast and Slow is indeed brilliant, but hardly the stuff of English classes. Then again, neither is Fifty Shades of Grey, currently sitting at the very bottom of Ladbrokes' list. It's okay; E.L. James doesn't need the money or fame anyway.

The people picking the winner are a select group: only eighteen members, all of whom are in the Swedish Academy. There are plenty of authors who are shortlisted year after year, and only awarded the prize after repeated consideration.

Recently, there's been a strong anti-American bias; four years ago, the Committee's secretary, Horace Engdahl, made headlines when he averred that "the U.S. is too isolated, too insular." As an American, I'd love to help make an argument to the contrary, but Engdahl has since stepped down, and the recent peace prize to Barack Obama implies that American authors do have a chance again to capture the Nobel. Maybe there's hope for Philip Roth this year.

So who do I think will win? I think Murakami has very good chances indeed, although he merits the prize less for 1Q84 than for The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which tackles the Sino-Japanese war among other things. I'd love to see Péter Nádas win for his monumental Parallel Stories, which is easily one of the most brilliant and dense books I've read since college. But the ones who are most likely to win are probably further down the list right now. The Dutch author Cees Nooteboom has been in the running for years, and has slowly amassed an extraordinary oeuvre that taps into great themes and gorgeous allusions. Adonis, a Syrian poet, consistently ranks among the greatest writers in Arabic, and his recently-translated Selected Poems is a wonder to read. And Salman Rushdie's books have probably had a greater effect on the world at large than nearly any other living author; his Joseph Anton gives us a small idea of his experience after The Satanic Verses and his subsequent fatwa. They'd all be deserving winners.

Go on, place your bets.

Image: J.M. Coetzee, the 2003 prize winner, giving his speech at the Nobel Prize Banquet. Credit: Nobelprize.org

The first day of Litquake, San Francisco’s annual literary binge, had some serious competition: on Saturday afternoon, the SF Giants were in the playoffs; Hardly Strictly Bluegrass drew hundreds of thousands to Golden Gate Park; the America’s Cup occupied the waterfront with 1%-ers; and it was Fleet Week, that quaint local tradition in which the Blue Angels tear back and forth above our city in a bizarrely irony-free celebration of America’s militarized cultural identity.

In a dimly lit room at the California Institute of Integral Studies, the thoughtful mood punctuated by the sonic rumbles of the Blue Angels, four writers of color gathered to talk about Rewriting America: Race and Re-imaginings in Post-9/11 America. This certainly wasn’t the Banjo Stage; things got serious, and political, and quickly.

“I am the new enemy,” said Francisco X. Alarcón, who identifies as Mexticoand is involved in the fight against SB 1070, the Arizona state bill outlawing cultural studies (and, effectively, literature by non-white writers). “Now that there are no Commies, they’re coming for people who look like me.”

Elmaz Abinader, a multi-genre writer who founded VONA: Voices of Our Nation Arts Foundation, the prestigious writing workshop for writers of color, began her reading of poems about Palestine with the observation that “America is the only country in the world where people run outsidewhen fighter planes fly over.”

Panel moderator Pireeni Sundaralingam read several selections fromIndivisible: An Anthology of Contemporary South Asian American Poetry, which she coedited with Neelanjana Banarjee and Summi Kaipa.Sundaralingam spoke of the difficulty in getting the book greenlighted in the face of publishing industry types who couldn’t comprehend that "South Asian American” writers are, in fact, Americans.

And Cave Canem Prize winner Ronaldo V. Wilson performed a chilling sound poem mashup: his own recorded voice recalling New York on the day the towers fell vs. his live reading of freewheeling poems touching on race, sexual identity, and class conflict.

Each writer discussed the complexities involved in existing outside of the mainstream in a country where people who look a certain way or practice a certain religion are now required to spend the bulk of their energy reassuring others that, as Sundaralingam put it, “We’re not terrorists.”

To end the afternoon, the panelists each doled out some quick tips for young writers of color — and for all writers.

On navigating the “establishment,” whether in academia or the publishing process:

“Go hard and strong on what you believe and don’t get pushed.”

—Abinader

“When they tell you no, you have to say yes. Don’t be so concerned with mainstream America; the gatekeepers will always be gatekeepers.”

—Alarcón

“Forget it — I’m just gonna make art … and let everyone else figure it out. [When I wrote my first book] I had an audience in mind: all the unusuals, all the freaks.” —Wilson

On creating a space for writers of colors within the larger literary scene:

“When you see other writers [of color] taking risks, support them — critique, publish, review their work, serve as their editors.” —Sundaralingam

“Everything you write creates a community around it. Go out and find it.” —Abinader

On the death of literary magazines, and the rapid disappearing act of arts funding in general:

“Think long term, invest in yourself. The institutions won’t survive.”

—Alarcón

“Defeat Romney. Keep arts consciousness alive. We can’t let this die.”

—Abinader

Great way to take stock of issues of race in the lit industry before what promises to be a week of copious — and often overwhelmingly white — literary scene-making in San Francisco. Now if only those damn planes would shut up, we'd be getting somewhere.

Images: Blue Angels photo via Paul Chinn, The Chronicle / SF ; Litquake logo via Litquake's Tumblr.

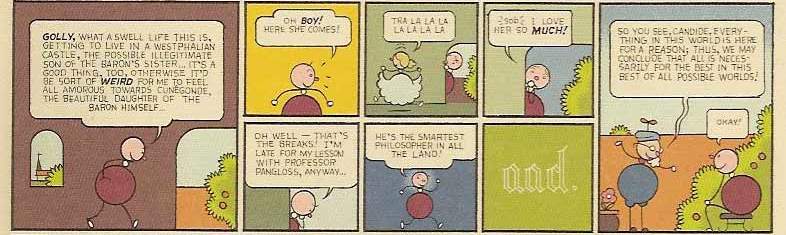

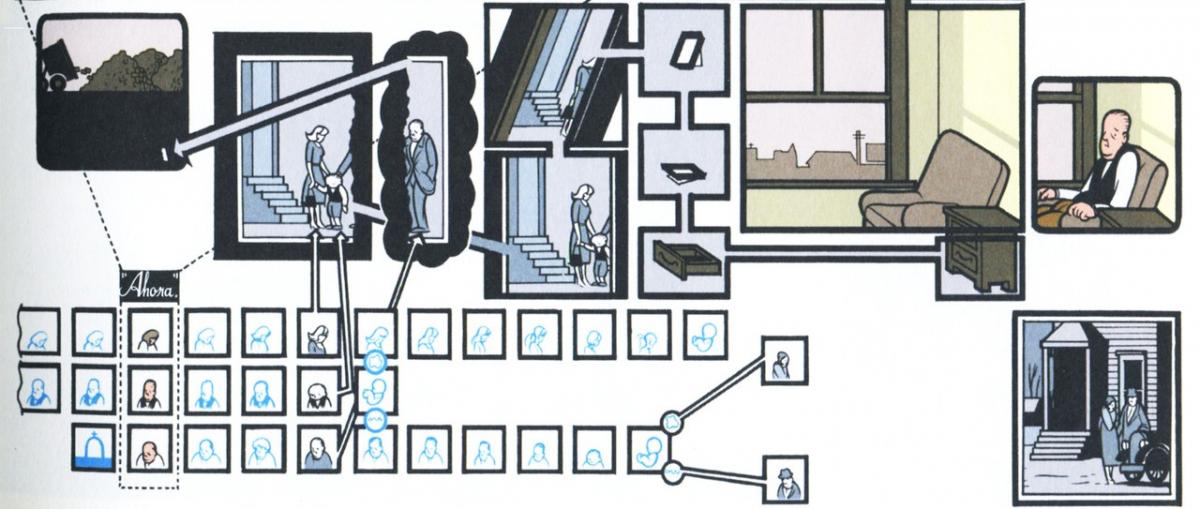

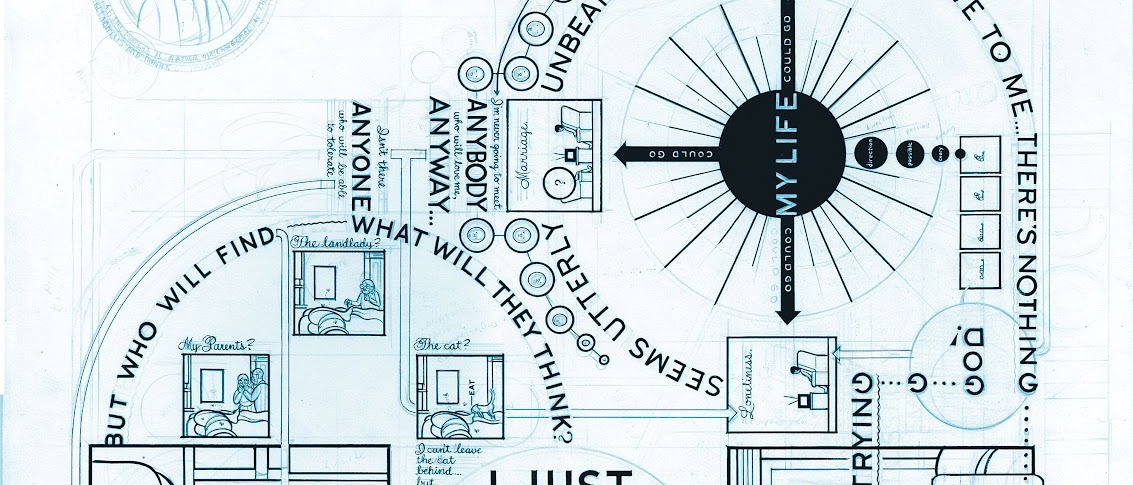

I walked through the pouring rain to the opening night of Chris Ware's gallery exhibition. His latest book, Building Stories, just came out, and I wanted to see the artistic process behind my favorite book cover and, well,

I wanted to see who else was obsessed with this graphic-novel master.

There were a few people who, like me, were sipping white wine and looking at the panels for the sheer enjoyment of it all. I first learned about Chris Ware when I held Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth in my hands. Not knowing what to expect, I had flipped through the book and seen a wide array of ligne-claire faces (just like Hergé's Tintin series!) and carefully proportioned panels that were way more complicated than the Batman comics I'd read in grade school. And this Jimmy Corrigan wasn't a little kid, either. He was a middle-aged man and his entire life was depicted in hundreds of pages, some without any text at all (including some beautiful montages of the sun moving across landscapes), and some swallowed up by a single panel. I was hooked.

I read this book when I was seventeen, so I wasn't terribly surprised to see a few high-school students with backpacks peering at the art gallery's walls. They looked, snapped pictures, and then texted their friends.

The title of Chris Ware's Building Stories is a double entendre, of course: even as he details the lives of various inhabitants within a single apartment building, he lays bare the ways in which he constructed those stories. I love sketches and other evidence of the artistic process, and so I wasn't disappointed to see

gigantic pages that swirled with text and images laid out in all directions. Even in the most chaotic pages, Chris Ware so clearly anticipated the human eye's motions that I was able to piece together the stories he was telling. And it wasn't just the eye that he understood; as I read the stories of men and women, children and adults, I realized that he had found a way to encapsulate the difficulty and beauty of human life into squares and lines.

Near the end of one panel, a mother tells her grown daughter that she dreamed she had found a book filled with everything she'd done in her life: "The point is, I dreamed [it up]... I saw it — made it — with my own two eyes [...] I just never thought I had it in me, that's all, you know? *snf* ... I never thought I actually had it in me..." I'm pretty sure Chris Ware himself walked past me at that moment, or at least I hope he did. He reportedly struggled over the years of Building Stories's creation; he mentions the almost complete loss of his virility, and he's notoriously press-shy. This was the first time I had seen that particular strain of grief, recognition, and summation immortalized in art.

I repeatedly squeezed past a man who was holding a baby. Another type of person I hadn't expected to see at a gallery opening. Maybe these comics looked kid-friendly on the outside? Or they were just looking at the model house built by the artist? Ware's characters are so driven by feelings of longing, guilt, despair, surprise, and sexuality that I almost worry about minors looking at them.

But out of Ware's honesty great beauty arises: sequential art that can modulate the passage of time and memory, that can move us (in one of my favorite panels, linked above) from a drop of water falling to a woman checking the time and, in her mind, seeing daisies. I knew I had to buy the entire Building Stories and open the box with its fourteen different booklets and posters and newspapers inside. I kept looking at the panels along the wall. I forgot all the unexpected people around me and lost myself in Chris Ware's square panels, solid colors, and clear lines.

All images by Chris Ware. Sources: fastcocreate.com; thefashionchronicles.com; arquitectoserectos.tumblr.com; nycgraphicnovelists.com; sparehd.com. Click on the pictures for full-page layouts.

Welcome to Clementine’s Weekly Reading Series, where Clem the hedgehog talks about whatever she is currently reading. This week: Mr. Penumbra’s 24 Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan.

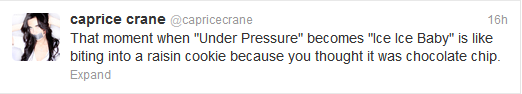

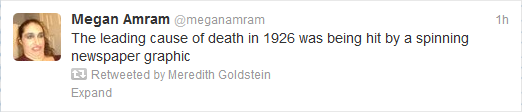

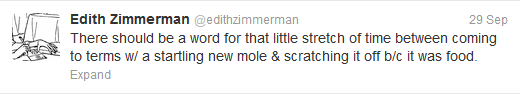

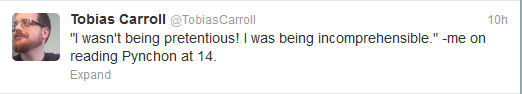

Read MoreIf brevity is truly the soul of wit, then your Twitter feed is the Algonquin round table of today's digital Dorothy Parkers and Ogden Nashes. Here's a selection of our favorite tweets from the week; nominate yours by submitting to @blackballoonpub with #twitwit.

Once a week, Black Balloon's editorial assistant Kate Gavino chooses the best Q and the best A from one of New York's literary in-store events. Here, Kate draws from Michael Chabon's reading at Greenlight Bookstore on September 17.

Tell us about your research process, especially using the Internet.

Michael Chabon: [The internet] is very tempting, encouraging you, whispering insidiously into your ear to indulge the need to know something immediately. Sometimes I feel like I actually pose those research problems to myself just so I have an excuse to check my email. Like say, how many spark plugs were in the engine of a standard issue US army truck that was used by the troops in Europe in 1944? You know you can find that. You know there's a whole spark plug website or military spark plug archive. It's there waiting for you, and it's very tempting right then to just get that information because a lot of the times you go looking, you find out way more than you bargained for. It's a great thing. Many times I've made important discoveries about books I was writing that I would not have know if I hadn't gone and done the research.

But usually, you can just put “tk” and leave it and go on and that took me a long time to learn. Most of the time it's just a lame excuse to go on Gilt.com and just waste time. Now I actually try to shut off the Internet, and that's really increased my productivity to a terrifying degree. I used to blame the fact that I have kids for the fact that I wasn't getting much done but it turns out it wasn't their fault. Well, it's partly their fault.

Last week, I ventured into a Minneapolis mystery bookstore to hear William Swanson read from Black White Blue: the nonfiction account of a St. Paul police officer killed in the line of duty forty years ago. The next morning, I learned that a man in Minneapolis had shot and killed five people, injuring several others, at his former place of employment, before killing himself.

Two things struck me: at the reading, the audience responded forcefully to the story of the assassinated officer and the subsequent legal case, but they didn't seem as interested in the tumultuous cultural environment in which the crime took place. And in Friday morning's paper, it was a line spoken by the Minneapolis Deputy Police Chief: "This is something we see on the news in other parts of the country, not here in Minneapolis."

For me, such a statement only conveys a desire to separate one's sense of regional identity from unwanted behavior. It communicates, most immediately, I am afraid.

The audience at the bookstore was, I can only assume, typical of nonfiction crime fans: most sat in bright, inquisitive attention as they asked about the specifics of the legal proceedings and the author's access to sources. The murder described in Black White Blue seems to have been entirely sociopolitically motivated: the State's case claimed the perpetrator was vying for the attention of the Black Panthers by orchestrating the shooting of a random white cop. Yet beyond a general description of the seventies as tumultuous, full of police brutality and politically very active (shit being blown up, etc.), very few specifics were brought up about the particular racial climate in St. Paul at the time.

At one point, Swanson said that in addition to the chaos, it was a rather exciting and liberating time, and the one black man in the audience pointed out that it wasn't exactly exciting and liberating for others in the community. I sensed that few attendees wanted to get anywhere near talking about the racism or police brutality or segregation or inequality. In this case, "not here" suggests a different kind of avoidance from the kind the Deputy Police Chief conjured after last week's shooting. But it could've been uttered just the same.

There is likely no better way to write nonfiction crime than to focus on a central character or pinnacle case around which everything else can be explored. Since last Thursday, the local papers have been focusing on two central characters: the shooter, Andrew Engeldinger, and his boss (who had fired Engeldinger that afternoon), Reuven Rahamim. Without fail, this story will be compared to other office shootings and other mass shootings, Colorado no doubt on the top of the list. I won't be surprised when op-eds begin to spring up about modern mental health practices and accessibility, the desperation of the economy, gun control. And other attempts at feeling productive after an event for which there is nothing to be done.

We will come together as a community and be defined by our response, our social activism, our Minnesotan sense of civic duty. Meanwhile, it might help if we stopped trying to cast certain behaviors as un-Minnesotan, so we could be able to move just a little further forward.

Image: Stringer/Reuters

Zadie Smith, in a recent Granta interview, mused that "the problem of life is basically: I only have one and it moves in one direction. People tend to seek all kinds of solutions to that dilemma, and the anonymity of technology has offered us a new kind of 'out.'"

I scribbled this on a piece of paper, so that I could see those words when I wasn’t working on my computer, and thought about my own novel. As I write it, I'm obsessed by the question of identity: how the self is defined, and divided.

I was once asked why my bookshelf had barely any titles published before 1950. My answer, then and now: I'm less interested in the theodicy of The Inferno or the social mores of Madame Bovary than I am in the perceptual miasma of American Psycho and the personal struggle for authenticity in Tom McCarthy's Remainder.

The philosophers to read on personal identity and the self — Derek Parfit and Thomas Nagel and Galen Strawson — are on my shelf, too. They all discuss identity from a personal point of view. Take Parfit’s thought-experiment: If I am perfectly replicated, down to my memories, on Mars, and my original Earthbound body is simultaneously destroyed, is my identity — memories and consciousness and all — continuous from one body to the other? (For the answer as well as further complications, read part 3 ofReasons and Persons.)

My question isn’t Am I the same person in these cases? so much as Do other people think I am the same person?

These problems are at the heart of Smith's novel, NW. They're not new problems, but she presents a relatively new solution: the Internet. Her characters change names, take on new virtual identities. The inverse, identity theft, is just as compelling: Dan Chaon's Await Your Reply (and let's not forget The Talented Mr. Ripley) exploits the divide between the self we experience and the self other people perceive.

Whether multiple people are occupying the same identity, or one person is shifting between many identities, the allure for readers is the same: the inside does not match the outside, and one person has to struggle to keep up — or confront — the lie.

We keep reading because we believe the truth will out. Oedipus is one of the oldest stories of mistaken identity, and we feel weirdly vindicated when the king realizes the real relationship between himself and Jocasta. But it took gods and prophets to bring out the truth; we have no such props in the arsenal of postwar fiction. We are more like The Man Who Folded Himself, watching helplessly as the same person splits in two, four, a hundred...

So we wait and watch for our characters to betray themselves? I certainly do. I want Adam Gordon in Leaving the Atocha Station to admit that he does not know Spanish. I want Patrick Bateman in American Psycho to realize whether he is hallucinating or not. I want Julius in Open City to acknowledge the horrible act his old friend accuses him of.

I want the truth; I suspect we all do. We want to see two lives collapse back into one. Maybe it will show us how to collapse the identities we, too, harbor.

image: thegreatbookslist.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©