When I was young, I had a vendetta against the word “or.” “It makes you sound undecided,” I told a friend, after reading her high school English papers. “Use ‘and.’ ‘But’ also works.” It wasn’t that I disliked the word per se; I just thought that conjunctions didn’t need to be used so much.

Four years later, one of my professors called me out on my predilection for closing lists without conjunctions. “You’re fond of asyndeton,” and she typed the word. She recited Aristotle’s thoughts on the technique in hisPoetics, and gently suggested that asyndeton was perhaps most successful if used sparingly. Churchill’s oratory aside, she was absolutely right. So I told myself to leave the conjunctions in, although I did keep a safe distance from “or.”

Then I read Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station. Nominally the story of a young poet living in Spain on a fellowship, the novel rests on uncertainty and consciousness rather than any particular plot. Reading of the narrator's struggles to understand and respond to the Spanish spoken around him, I noticed how he used “or” as a way to juggle many possible meanings: "She described the death of her father when she was a little girl, or how the death of her father turns her into a little girl whenever she thinks of it..."

Lerner discussed this in a BOMB interview: "Yes, “or” is an important word in the book, especially in those scenes where Adam Gordon can’t tell if he’s following the Spanish of an interlocutor, and so, instead of simply failing to understand, understands more than one possible meaning at a time ... Hearing a Spanish sentence as X_ or _Y allows him to keep his exchanges from becoming actual, to keep them in the realm of the virtual."

“Or” as a marker of uncertainty, yes—but Adam Gordon, the narrator, shifts the need for actuality and certainty onto his readers and listeners. The premise of the novel is that the narrator is constantly plagued by the need to feel authentic and transcendent; his intentional use of “or” forces other people to make that decision for him. He lets himself live in uncertainty.

Is “or” the conjunction for our time? Adam Gordon drowns in polysyndeton in the wake of the 2004 Madrid train bombings—an event many people grieved over as on 9/11. The words I remember from that time, though, were authoritative. On the radio, people reread Auden’s “September 1, 1939,” where Auden memorably uses “or” to oppose: “We must love one another or die.” The conjunction didn't seem uncertain at all, actually.

“Or” seems less definitive, less divisive now than it did in 2001 or 1939. Robyn Cresswell pinpoints a contemporary, perhaps more honest direction in his appreciation of Thomas Sayers Ellis’s “Or,”: “The poem begins, as I read it, by riffing on the either/or logic ... But it quickly ramifies into geography, history, poetics.” Perhaps “or” isn’t quite so terrible; maybe it’s as a way of conjoining many different coexisting possibilities, but without rejecting any of them or forcing us to choose.

Image credit: http://wandahamilton50.com

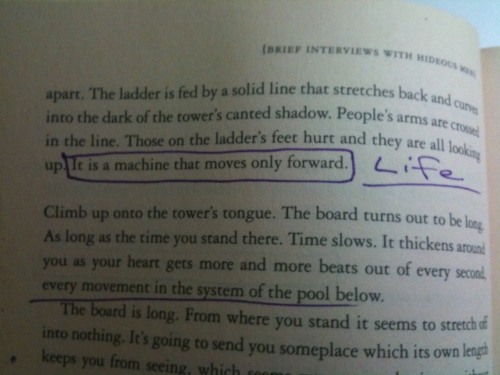

The inner blogosphere of Black Balloon has been abuzz with fake authorial gushiness versus real teen gushiness versus the gush-worthiness of David Foster Wallace faking out teens for real. And this past week, when a package of my old books arrived from my mom, complete with my own teen copy of Wallace's Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, all three confluenced in a cosmic and darkly underscored conclusion.

Read More

In a recent Harper’s interview, Ben Marcus (whose new book, The Flame Alphabet , is due out in January) mentions an idea that I’ve recently become obsessed with. The idea is that every writer has one essential story (also known as the "object") to tell—one fixation that must be explored again and again, revised and retold endlessly but never resolved.

For Marcus, the story is this: “A man is in a hole where bad things are happening to him.”

He explains that he has “to work to mask this basic fact,” work that I assume consists of the changes Marcus mentions earlier to style, tone, story or storylessness. I love this idea. If I could, without embarrassment, I would ask Marcus when he knew this story was the one. And yes, I would ask it with the same high-pitched giddiness a school girl asks about true love.

I’m familiar with the notion that all writers have their particular ticks—distinguishing characteristics that are separate from their particular style or voice. For me, it's hands. Hands show up all over the place in my fiction, touching things as a way of knowing, as reassurance. Why? Because hands are trustworthy, obviously. But the idea that they're part of my one story? Rather than feeling limited, I find the idea absolutely exhilarating. I’m not sure if I can entirely explain why, it feels both reassuring and stimulating. And I don't care at all if this idea is actually true or not; I’m still throwing myself in.

I understand that finding your story/object is a lot like asking the question, What’s wrong with you? Hours of psychoanalysis might actually be helpful in this pursuit. But could it be dangerous to know your story? As much as I’m fascinated by the idea, I’m also a little superstitious about answering the question. To miraculously behold my object? Then I’ll know what to do! Fuck. It’s almost like playing the field before getting married. I obviously date the same person again and again, but if I found the one I’d have to acknowledge this limitation in myself.

A part of me wants to know so I can just attack and attack and attack, but another part of me wants to keep my obsession to my subconscious, at least for a little while longer.

Photo: excursuses.wordpress.com

The White Review''s current issue has a stunning example of High Intellectual Preposterousness. Lars Iyer has written a manifesto calling for an acknowledgment of the end of literature:

The only subject left to write about is the epilogue of Literature: the story of the people who pursue Literature, scratching on their knees for the traces of its passing. This is no mere meta-gamesmanship or solipsism; this is looking things in the face ... It’s time for literature to acknowledge its own demise rather than playing puppet with the corpse.

Is he serious? This is silliness, this is absurd. From the style of the manifesto itself, it’s hard to judge whether he’s being satirical or sarcastic, or if he’s really asserting what he believes to be true. Manifestos are full of pomp and grandeur, drenched in language that is bombastic, declamatory. Iyer’s is no exception. So I hunted the internet in search of his true intention and found that no, he was not joking. In a 3AM Magazine interview, he elaborates:

It is not simply that the relationship between literature and community has collapsed, nor even that literature is no longer in contact with politics. For me, the meaning of literature itself—the very possibility of literature—has collapsed. Literature, like left-wing politics, seems impossible ... I can only say that it seems to me that literature has, in some fundamental way, run its course.

What does this mean, "literature has run its course"? Is that why Iyer's book, Spurious, is so interchangeable with his blog, Spurious? To me, this is like saying sex has been slain by pornography, that eating is over because of fast food. People will always fuck and eat. Fucking and eating aren’t destroyed by depravities and deformations in their use. Yes, there is history and influence and philosophy and modern practice and all the rest. But there is still choice and there is still necessity.

Literature does not die, there is no end in it, it is something we do.

Rather than spend more time in inquiry and exasperation over this high intellectual dreariness, I’d like to simply present some evidence to the contrary. For intelligent discourse concerning the interaction of literature and culture, primarily in terms of how some of the more powerful influences and gatekeepers of culture present literature, I suggest an interesting piece by Roxane Gay up at the Rumpus. To see the existence of a literary magazine partially initiated because “we are tired of hearing that literary fiction is doomed,” check out Electric Literature. And to hear from a true professional about his interactions with the great beast of literature, I highly recommend this interview with Ben Marcus from Harper’s.

A quick glance at any one of these demonstrates that literature has not run its course, and, for a great number of people, does not seem impossible.

Photo: living.oneindia.in

As much as I believe my intuition to be above reproach, it’s nice to have a little science come along to back my shit up. Days after I posted about putting things in boxes, I came across a vindicating Jonah Lehrer article in Wired: it seems that scientists have proven that restrictions trigger the brain to perceive on a larger scale and to conceive of a greater range of ideas, thereby boosting creativity. Thank you, science!

Now that imposing form (aka my favorite kind of restriction) has been sanctified as awesome by the brain masters, I feel compelled to push the envelope a bit further and bring in the frail, curmudgeonly matter of intention. To be clear: by form, I mean the shape of a piece of writing; the way in which content is organized on the page. It's easiest to imagine the imposed form of a sonnet, but any variety of form can just as easily be imposed on any piece of writing. You could set out to write a short story beginning every sentence with the letter Q. You could limit the syllable count in every paragraph, use only monosyllabic words, end every paragraph with a different color.

Now, imagine an idea of what you want to write about and an imposed form are fighting. Do you know who is going to win? Form. The answer is Form. Why? Because form owns you. Because form is more necessary to the achievement of beauty than some idea you had. Form takes that idea and makes it better—science says so.

As soon as an idea finds its way into language, it is trapped by the rules of grammar, coherence, effect. What is written supersedes the idea that compelled the language onto the page.

In other words, what is read are the words put down, not the intention behind those words. No author can whisper into the ear of every reader to explain what they meant. But this imposition, this forcing of an idea into language, in turn allows that idea to be explored, tweaked, and revised more fully. If I get the idea in my head to write about pancakes and how delicious they are, chances are, if I set up some limitations for myself beforehand, if I make the adventure of writing more challenging, I will be forced to enter more interesting territory.

Pancakes could achieve greatness. Pancakes could bring you to your knees. One of the greatest side-effects of form is that it’s likely to push intention further into an unexpected, delightful place.

Photo: coloringes.com

Why are publishers often so bad at marketing? Daniel Menaker’s piece "Flap Rules" on BarnesandNobleReview.com points out some of the more grating redundancies slapped on recent fiction: always use "stunning," always use "deeply," find a way to work in "best-selling."

But as aggravating and uninformative as these phrases are, things could be worse.

On the back cover of a Freud paperback I recently purchased, I was astounded to read this (I’ve taken out some specifics so that the poor publishers might remain anonymous):

...widely considered to be one of his greatest works of all time. This great work will surely attract a whole new generation of readers who study Sigmund Freud. For many, [book title] is required reading for various courses and curriculums. And for others who simply enjoy reading on human psychology, this gem by Sigmund Freud is highly recommended...would make an ideal gift and it should be a part of everyone’s personal library.

The copy is almost mesmerizing in its continued propulsion of disappointment. This great work is really great. If you study Freud, reading Freud will be required. A gem, highly recommended, an ideal gift. Stripped of any specificity beyond the mention of "human psychology," this paragraph could have been written about Freud or a Rich Dad, Poor Dad title.

I understand that writing book copy must be a chore—not unlike the experience of writing a cover letter for an obscure job opportunity—but could it also be intentionally designed to greet the reader with a kind of anonymous familiarity? That if we read "stunning" and "deeply" enough we will come to desire those books described as "stunning" and "deep"? If these tricks aren’t effective, surely publishers would stop writing copy in this way. Do readers merely skim flaps and back covers waiting for the right words to affirm their choice?

Perhaps my reference to the heinous Freud copy is, in fact, a Freudian slip: perhaps we hark to book flaps for Father's approval.

Image: blogs.yis.ac.jp

With Charles Shield’s new biography of Kurt Vonnegut, And So It Goes, being reviewed all over town, I keep seeing the cartoon Vonnegut head. With each successive viewing, which is of course reminiscent of Vonnegut cartoon head encounters of the past, I become more and more convinced of the appropriateness of the image. Vonnegut has cartoon qualities: the downtrodden acceptance of fate, his unavoidable sentimentality, his common way of speaking for the utilization of common sense. Vonnegut was a bit of a goofnut. But I also see, in the vast proliferation of his image as cartoon, just a sliver of animosity. A certain satisfaction in our ability to put Vonnegut in his place—as a caricature.

One of the major concerns of Shield’s biography is to address the contradictions between Vonnegut’s image and how he was in real life (what pretty all biographies set out to explore, right?), but also to bring to light just how in control of his image Vonnegut really was. Not that Vonnegut was merely playing the fool in order to endear himself to an audience, but that he actively pursued an image that would sell. Which doesn’t fit all that snugly with the image of the good-hearted, simple-minded goofnut.

I’ve always been rather protective of authors’ private lives. I’m inclined not to care about the person but to behold their work. Yet with someone like Vonnegut, whose presence was so adamantly inserted into the page, distinctions between narrator and author, character and autobiography, blur. Should we be alarmed? Do we now have to question the narrator of Slaughterhouse Five as insincere?

Before such madness unfurls us, let me propose something. Reading Vonnegut had an extraordinarily positive effect on me as a teenager. Here was an author ready to tell you the true stupid shit about human beings but who still asks you to be decent. Vonnegut, as simple-seeming as he may have been, attained a kind of nobility to aspire to. As much as the true man may have failed in coinciding with his ideal image, isn’t it still significant that he sought out attempts at decency?

Photo: NYTimes

There’s been some talk on the internet about being embarrassed to talk on the internet. Htmlgiant has a post about being embarrassed over sharing one writer’s favorite poems in the context of htmlgiant, which spreads to a post on the writer’s personal resistance to participating in the kind of social/group context that htmlgiant inherently is. But htmlgiant is a particular literary online context, in which expressing one’s personal embarrassment is fairly common: there’s a recent post on the humiliation of being a writer, encouraging further confessions of other people’s thoughts on the humiliation of being a writer.

The general form that many literary posts take is one of confession: addressing first the writer’s justifications or apologies for speaking in the first place before moving on to discuss the issue at hand. To an extent, these confessions create a sense of intimacy between reader and writer, but they also tend to make the piece of writing more about the speaker.

Freud said, “...every individual is virtually an enemy of civilization, though civilization is supposed to be an object of universal human interest.” All groups press for the individual to fall in line. There’s no way around it. But there’s also the possibility of greatness in numbers, which I was surprisingly reminded of last month—an abrupt encounter with the New York City Marathon.

To add my own confessional preamble, I might have been in an emotionally delicate state due to my triumphant hangover. Nonetheless, when I rose up from the subway and heard the mass cheering, when I saw the crowd of strangers applauding and whistling for other strangers, I almost started crying. I do not like crowds, and yet here I was, ready to hug and weep with all of them.

Without doubt, a large, public group of strangers calls for very different codes of behavior than an anonymous gathering online. The street doesn't allow us access to every spectator's feelings about being there (only I get to do that). But maybe we could try emulating a similar kind of enthusiasm that lacks this uncomfortable, stilting sense of self-presentation that seems to be plaguing internet reviewers. Maybe we could pretend that the crowd is gathered for a different purpose than staring down whoever speaks.

Really, how hard would it be to inject pure, unabashed celebration into the internet? To simply cheer and gush over that which excites us?

Photo: rosemis.com

When it comes to understanding art, the best intelligence I can muster compares to that of a wildly imaginative but heavily sheltered five year-old. Confronted with the work of someone like Maurizio Cattelan, whose retrospective is up at the Guggenheim through January, I’d rather not be alone with it. Someone else should be there, holding my hand, condescendingly telling me what the fuck to do with it.

I mean, I know all about the color wheel. The color wheel doesn’t faze me. Photographs are simps because photographs are immediate; they have beauty or depth or they don’t. But objects? I have to interact with objects? Immediately, upon encountering things constructed or appropriated as art, I assume there’s something going on—likely something obvious—that my wee brain has zero access to.

Image courtesy of artdatabank.blogspot.com

As much as I have this hesitating self-consciousness, I also suspect that intellect, in the face of art, doesn’t count for shit. And that my encounter with art, regardless of how much of an idiot I appear to be, should a) occur absolutely between myself and the art alone and not with a hand-holder and b) provoke a good deal of feeling. Art can provoke thought too, of course; thought’s okay and all, but it can’t only do that. I can bravely go forth and encounter art—even objects that are art—because it’s the art’s job to move me. Art has to seduce; it has to capture my attention with enough authority and grace for me to want to remain in the encounter for as long as possible.

Image courtesy of artdatabank.blogspot.com

If I were honest about my feelings toward Maurizio Cattelan, I would begin by confessing that I simply enjoy the sound of his name. Second, rumor has it he’s a bit of a hot mess who’s kind of consistently giving the art world the finger, which to me communicates charm. I was hesitant to encounter all of his work all at once; I would have preferred to take each piece on its own. Surprisingly, after the overstimulating first attack, which serves its own interesting purpose, I actually found that encountering the pieces all at once granted a sort of permission to peruse at leisure. I became more open to actually engaging with each individual piece because of the nonchalant, clusterfuck mess of it.

But most importantly, I have a hard time looking away from the elephant.

Image courtesy of artnet.com

I can’t get into the gamut of what happens in my heart and my head, because that’s between me and the elephant. All I can tell you is that I need to go look again, because the elephant hasn’t stopped the promise of telling me everything terrifying, everything beautiful.

Every weekend of the summer, I pitched a tent along the East River to sell pasta at the Smorgasburg.

The pasta I sell is organic, comes in over 70 flavor varieties. “Do you make the pasta?” is the question I get asked the most. “I don’t,” is the answer. It’s made near Rochester by a bearded man named Jon who makes the 6-hour drive to Brooklyn once a month to deliver a few hundred pounds of dowel-dried noodles.

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©