As Alexander Chee recently wrote in a lovely essay for the Morning News, we should all definitely go to writing colonies as much as possible. But not everyone gets to chill at Yaddo with the lit stars. So how can a writer acquire that enviable writing-colony glow if she’s not experienced enough, lucky enough, or possessed of enough free time to chuck it all and head to the woods?

Good news: people, especially those who don’t fit perfectly into the traditional literary establishment (see also: women, genre writers, people of color, people with day jobs), have been writing for centuries without delightful daily lunch baskets waiting for them on the steps of their light-filled studios. People even write without MFAs, or Twitter followings! We write wherever we can, however we can, and we get our life stuff done and manage to keep on writing.

Here are a few suggestions for writers without a (free) room of their own:

1. Weekend Quarantine, otherwise known as “staycation.” We know, your apartment is small and filled with distracting stuff, and your roommate blasts Taylor Swift all night long. You know who has a nice apartment? Someone else. Ask a friend if you can swap places for a weekend. Keep your eyes peeled for housesitter gigs. Basically, try to spend a chunk of time anywhere that is different from the place in which you normally write. NB: Working in a café won’t cut it. You need space and quiet if you’re ever going to replicate that magical “I’m Only Here To Write” feeling.

2. Once you’ve scheduled a Weekend Quarantine (or its younger cousin, the Day-Long Writing Binge), take care of any creature comfortsbeforehand: Stock up on food and coffee, and pre-plan your meals. If you’re really persuasive, maybe you can get an elfin friend to deliver you a lunch basket, but leftover pasta will probably suffice.

3. Go to the library. Have you heard of these places? They’re amazing. They are full of books and electricity and you can get stuff done in there! And they are free.

4. One of the best things about colonies is the interactions you have with other artists while you’re procrastinating — er, processing. To get a hint of creative cross-fertilization, begin a writing session with some non-writing. If you write prose, read a poem; for a different view of the world, peruse a book of photography or paintings for ten minutes. And listen to music. (I prefer music without vocals — my go-to writing albums are Coltrane’s Africa Sessions, Chopin piano pieces, and anything Explosions in the Sky, Dirty Three, or Electrelane.)

5. Log onto your Facebook profile. Go to the little “account menu” arrow in the upper right hand corner (or wherever they’ve moved it lately). Choose the option that says “Account Settings.” Choose “Security.” Click on “Deactivate your account.” There, you've just cleared hours a day off your schedule.

Extra Bonus Pro Tip: Don’t sweat the scene. So you’re not besties with Andrew Sean Greer? So what. Suck it up and write, already.

Image courtesy the author

While I find it very exciting (and positive!) that the naughty vs. nice criticism debate has so thoroughly made the rounds, I’m starting to wonder if people have forgotten that the internet isn’t just about commenting and connecting; it’s also about doing things differently. To me, the fuss isn’t really about being too nice (frivolous) or mean (unproductive). The real issue is that people demand better writing from their criticism: criticism that demonstrates an honest, thoughtful engagement with the book at hand regardless of attitude or posture.

Let me be very clear: personally, I think meanness and cruelty can be exceptionally funny. But I have my suspicions that in this day and age, in the panicked pleas for attention, attitude often usurps critical engagement because that approach gets hits. My issue with the much despised William Giraldi review of Alix Ohlin is that I learned more about William Giraldi — how important it is for him to show us how smart he is — than the books he was reviewing. Book reviewers (traditional ones, anyway) can totally go ahead and be scathing and super mean, but they should be tearing the book apart so we know what’s wrong with the book, not what’s right and self-righteous about the reviewer.

But! We don’t have to live like this. This is the internet. We don’t have to play within the rules of naughty or nice. The Times Literary Supplement,Harper’s, and sometimes the New Yorker still contain very good, serious reviews, but we can also help foster a literary environment that is more interested in exploding the conversation than ending a dialogue at "good" or "bad." Take any shitty book and analyze the decision to write it in the first- or third-person — and then discuss how this may mirror or contradict the "modern experience" of the grocery store, text messaging, OkCupid. How does the author grapple with new media, and how do those choices affect our sense of authenticity? Throw the book into the mortar of anthropological linguistic analysis of pronoun usage. Identify the author’s tics and psychoanalyze the crap out of the poor person who made the mistake of showing their book to you.

There are countless games to play beyond Billy-said-he-likes-it-but-Suzie-said-it-stinks. The Millions, Flavorwire, and BrainPickings have shown that there is serious fun to be had plowing through literature, whether it's top ten lists, favorite quotes, or essays on craft or writer's conferences, and there's no reason we can't invoke that same sense of seriously engaged, enthusiastic play when it comes to reviewing. What I want from criticism is thoughtful engagement with books, the ideas they spread, and the processes by which literary effects come about. While traditional book reviews can and will still accomplish this, there is ample space for criticism that is concerned less with assessment and more with exploration — with enlivening the ways we talk and think about books.

image: doanie.wordpress.com

The Millions recently proposed the idea that if MFA graduates were finding themselves unsatisfied with adjunct teaching (which, um, obviously), they should look into teaching high school. Nick Rapatrazone, the post's author, does make some pretty sexy arguments for giving your time to sweaty, self-interested quasi-adults who are horrifying at being adequately human toward one another. Still, I’d like to supplement his advice with a few second thoughts.

Let me be clear: if you’re into teaching high school, I applaud you. The prospect of a bunch of MFAs entering the public school system with enthusiasm and literary encouragement fills me with excitement and something close to glee. But as long as we're weighing it against adjunct teaching, I feel other perspectives might be of use.

Maybe try being poor for one minute. This is not to encourage anyone drowning in adjunct drudgery to continue drowning in adjunct drudgery. You are a sucker and totally not being paid what you’re worth. If you get some weird sadistic glee out of the it, please, by all means, keep encouraging universities to crumble under the weight of their own lack of integrity.

But I have to ask: since when were writers supposed to be comfortable? You really want to have to go back to high school just so you can pay rent? In this economy, I say take whatever shitty job you can get. But I also suspect that there’s this lingering hope that getting an education guarantees some future stability in a fulfilling career. I kind of have the feeling that the whole MFA-to-high-school-teacher track is an adjustment, a concession to the dream that was really only for the generations before you. That shit was for the baby boomers and whatever unnamed generations became between them and...what, Gen X or Y? You need to talk to your grandpa (great grandpa?) about the Depression and lard on bread and some shit 'cause you want way too much.

My point here is that if you want stability while you write, be an artist who doesn’t need the approval of a teaching career. Stop thinking you’re owed something because you went to school. School was a privilege you lucked out on. If you write, worry about writing and don’t give a shit about anything except forming your life to allow writing to happen. And if youstill want to teach, god bless.

People who went to school for teaching K-12 are turning away from careers in education. My own mother, an excellent and incredibly dedicated public school teacher for over thirty years (and counting) has said she probably wouldn’t have gone into teaching if the atmosphere had been the same as it is now. This largely has to do with the sheer amount of time spent on test preparation for tests that don’t actually result in students learning anything. I find it horrifying that teachers no longer have as much discretion in what they teach, and I find it doubly horrifying that potentially excellent teachers might be turning away from that career because education is now such a shit show. Sure, steady paycheck, making a difference, etc. etc., but anyone going into teaching high school English under the impression that they’re going to teach kids how to appreciate literature should know that such labors will account for maybe twenty percent of their workload.

I hope with all my heart there are folks out there who will fight to make public education better, whether from the classroom or the capitol. But, my fellow MFAs, just know that it will indeed be a fight.

image: bestofthe80s.wordpress.com

For reasons unknown to me, this story about a St. Paul man threatening a 62 year-old woman with a sword over a borrowed book has gotten way toomuch press. As a fan of St. Paul, and in the spirit of promoting the Midwest as a fairly decent place to write, I’d like to dwell on some of the story’s finer aspects.

Books matter to Midwesterners. As far as I can tell, the whole ruckus began when the suspect threw the book he had borrowed onto the floor, and the kindly loaner of the book gave him a little shit about it. Not only does the woman here acknowledge the value of books by suggesting they don’t belong on the floor, but the borrower, by his swift decision to get a weapon, suggests that he, too, knows the import involved here. If the guy didn’t think it was a big deal to throw a book on the floor, why would he bother brandishing a sword? It hard to imagine any of this happening over a Gilmore Girls DVD.

Midwesterners have Scandinavian impulses regardless of whether they are actually Scandinavian, and Scandinavians are insanely afraid of getting called out on something they did poorly. Scandinavians are also almost godlike in their ability to bring shame on others. We have here the genius of seemingly innocent Midwestern passive aggression: the woman suggested he just throw the book away if he were going to leave it on the floor. She doesn’t accuse him directly of doing something shitty but suggests that he might as well have done something shittier. Most people have likely expected the worst from him his entire life. And the poor guy, who later in jail admits he is an idiot, can’t help but get emotional: he, too, is caught up in the Scandinavian shame cycle.

And then there's his choice of weapon. A sword. Really? Most people I hang around with aren’t really prone to take an unsheathed sword as a threat. A gun? Sure. A big knife? Oh yes (more on that in a second). But a sword? From a kid who also has ninja stars and nunchucks? If it weren’t for the sword, there would be no story. Whatever the guy’s intentions, he has succeeded in provoking a great amount of curiosity. He might not be a good neighbor, or a good criminal, but he has proven that minor criminals can still surprise us, and that sometimes people’s small quirks get the most attention.

Saturday's frightening incident in Times Square lies on the opposite end of the blade-wielding spectrum. While our book borrower's actions provoked lots of trashy curiosity, the killing of Darrius Kennedy brings up a whole lot of actual fear. His standoff with the cops, the bystanders, and the rolling cameras of a hundred smartphones was not funny; it was chaotic and very sad. For all we know, both men might have begun with the same small, dumb impulse: a trigger response to a mix of panic, fear, helplessness. Our book borrower only briefly acted on the impulse. Mr. Kennedy took it to the limit.

Image: faildaily.blogspot.com

It's mid-August, aka prime vacation time, so we at Black Balloon decided to let our beloved Siri roam free. Here are her latest dispatches from Johannesburg, South Africa!

The safari truck is waiting and the air is cold; the August chill awaits Siri and her cohort of American onlookers. Once they board, they look out at the broad, rutted road leading away from Johannesburg and toward the velds.

Through light and shadow the truck travels on. As the lounging animals of the safari park come into view, the oohs and aahs of the group grow louder, and slowly fade away.

After its off-course trip away from lions and ravenous, red-clawed nature, the safari truck and its tight-knit fellowship of riders find themselves in an unrecognizable veld not far from Thohoyandou. As men working nearby come into view, the truck stops.

Unable to talk to their compatriots in Hausa, Afrikaans, or Xhosa, Siri is called upon for help by her kindred safari-goers.

The grasses part as the safari truck and its grizzled driver make their way toward, they hope, some sign of civilization. They pass a few gazelles and insist that Siri help them orientate themselves. In the distance, a battered truck full of armed men bounces towards them, sending up a trail of dust as the safari-goers watch with increasing alarm.

[Co-written by Anjuli with help from ifakesiri.com]

image: kellyjstoner.wordpress.com, with Anjuli's iPhone photoshopped in.

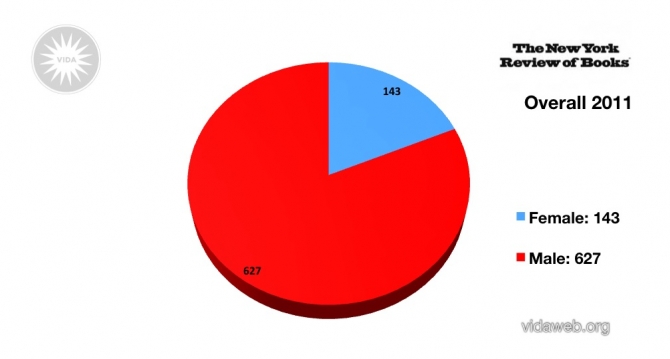

Since I came of legal drinking age, I've been bringing books to bars. I pair literature with libations at home (whisky, usually, with or without the “e”), so why not do the same at my local watering hole? Trust in some shrill Yelpers to question the practice: “Why are people sitting at bars reading books??? It's not a library...I know Bukowski is cool, but I'm sure he had no part of this kind of debauchery.” Love it or hate it, the recently opened Molasses Books in Bushwick is bringing these two hobbies/passions/addictions closer than ever, offering tipples and tomes under one roof.

Its liquor license is still in the works, but Molasses and fellow newcomer Human Relations (a short trek up Knickerbocker Ave) have advantageous locales. Bars and art pair well in Bushwick, and I think books will, too.

Now, I understand this goes against the grain of bar dynamics. Inhibitions drop as intoxication increases, people start chatting and—sometimes—stuff happens. I engage my mingle-mode at gallery openings, and I'm not totally aloof at bars, either. This is why my preferred joints for focused reading are dives.

Take the now-shuttered Mars Bar. Despite its sticky surfaces and dodgy characters, everyone kept to themselves, hunched over their spirits of choice. While Mars Bar didn't boast a wall of whiskeys, if you ordered a shot of Jack Daniels, you received an overflowing tumbler of it. Since I was going to be there awhile, I could make major progress in brick-sized books, like Neal Stephenson's historical sci-fi behemoth The Baroque Cycle.

I take a cue from Haruki Murakami's everymen (sometimes only dubbedboku, i.e. “I/me” in the masculine sense) who hemorrhage hours in bars. Often, they arrive with an armload of Kinokuniya purchases, like Tengo in1Q84 or the sleuthy narrator of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Nobody questions why they read in bars; it's just second nature. So when I meet friends for dinner in the East Village, I typically hit basement sake saloon Decibel first, ducking into the narrow bar with whatever novel I scored from St. Marks Bookshop down the block. Nursing chilled shochu, I'd study my grammar handouts from the Japan Society and, on occasion, try impressing the female barstaff with just-learned vocabulary.

This is why I avoid reading in Tokyo bars: chatting with barmates affords excellent Japanese conversation practice. Plus my abilities improve after I've had a few. My preference for ultra-tiny Golden Gai dives and immersive fetish bars sorta distract from the prose, anyway.

Lorin Stein, The Paris Review's editor, proudly brings books to bars, though his hangouts have changed after favorites faced renovations. My book-friendly biker bar Lovejoys in Austin, TX, recently tapped its final draft. Lovejoys also attracted tattooed, Bettie Page lookalikes, so I admittedly didmingle there.

While I search for my next haunt, paperback in hand, I ask you: are you a bar reader? Does a particular book entice you toward a bit of boozing? All experiences and inspirations welcome, and the first round's on me.

Image: The Gents Place

“I don’t want to read a book in translation,” my friend declared. “It’s not as good as reading the original.”

I put down my beer with a thud. I couldn’t even reply. The comment seemed to confirm a depressing statistic I had read in The Economist: “When it comes to international literature, English readers are the worst-served in the Western world. Only 3% of the books published annually in America and Britain are translated from another language; fiction’s slice is less than 1%.”

I wanted to pull out a copy of Anna Karenina—sorry, Анна Каренина—and show my friend the Cyrillic text. I ought to have said, “You mean reading a book you can’t understand is better than reading one you can?” Or, “I can barely correct my brother’s Spanish grammar, and I sure can’t read New Finnish Grammar unless it’s in English.”

Fortunately (or not), I had the self-restraint to change the subject.

America, go to our bookstores and look at the “Classics” sections. Homer,Cervantes, Dante, Flaubert, Borges. We owe our literary history to these authors and the intermediaries—Robert Fagles, Edith Grossman, Allen Mandelbaum, Lydia Davis, Andrew Hurley—who have carried the texts to our Anglophone shores.

It doesn’t matter how many MFA programs we have. It doesn’t matter how brilliant our living writers might be. Our own literature would still be barren without those foreign incursions. Even our earliest English classic isBeowulf, and I read it in Seamus Heaney’s resounding, earthy translation. Ask a budding writer if they’ve read Bolaño, and they’ll most likely nod enthusiastically, half-aware that Natasha Wimmer made possible their enjoyment of The Savage Detectives and 2666.

Among the alarmingly low number of publishers who will do books from other countries, we have Open Letter, Europa, Other Press, and a new player: Peirene Press. The wonderful thing about Peirene is that, although it publishes exclusively literature in translation, it focuses first and foremost on sharing a great story with each book. Their novellas take as little time to read as it does to watch a film, and the publisher holds events to discuss each book. She's a salonniere, and she's a success. She’s actually getting people to read something they might avoid if they knew it was “foreign.”

America, there’s a new direction for us. We don’t need relatable authors; we need strange and wonderful and new stories. I’d rather talk about good books than nice authors any day. Let’s skip the usual crop of MFA workshop pieces about the Brooklyn Promenade.

America, let’s publish Icelandic writers (Steinar Bragi!) and Argentinian writers (Pola Oloixarac!) and Mauritanian writers (Ananda Devi!) and make them worth reading. I wouldn’t know where on the map Iran is, or why I’d want to visit, unless I’d read Censoring an Iranian Love Story. I want to read something nobody in America would risk writing. America, let’s open our eyes to the rest of the world.

America, let’s make foreign literature sexy.

image credit: redsurproducciones.blogspot.com

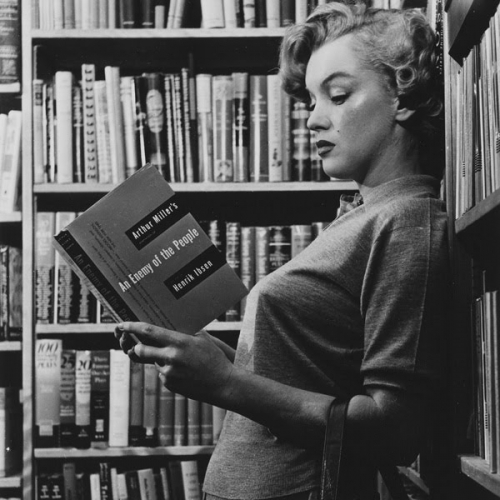

I haven’t been a lifeguard for years. But when I walk past the freshly reopened McCarren Park Pool and get a whiff of chlorine, I realize there are some things I haven’t really forgotten. The positions for performing CPR. The office cubbyholes where we stashed our keys while on duty. The way the light on the water changes from six o’clock, when the sun starts setting, until the pool closes at eight.

To the children in the water, we are like the gargoyles on an old cathedral: instantly recognized, immediately forgotten. If we are gargoyles, they are wide-eyed pilgrims, in love with water. They swim with inflatable wings, water noodles, kickboards, flippers. They swim in the shallow areas, then they go deeper, then they learn how to dive. We watch them come back over days, months, years.

We perform the same rituals day after day. We unlock the bathhouse doors. We hand each other our foam rescue tubes as we climb up and down the lifeguard stands. We loosen the lane ropes, turning six-foot-tall wheels, until they have been coiled up on a reel aboveground, only to unroll them again later in the day.

The water circulates through the filters and the pumps, always the same water.

• • • •

One winter, I went to the Whitney, and saw a series of photographs by Roni Horn of the River Thames. As I looked more closely, I realized that the pictures had been superimposed with tiny numbers. Below the photographs were numbered footnotes.

61. Is water sexy?

62. Water is sexy.

63. Water is sexy. It’s the purity of it, the transparency, the passivity, the aggression of it.

64. Water is sexy; the sensuality of it teases me when I’m near it.

65. Water is sexy. (I want to touch it, to hold it, to drink it, to go into it, to be surrounded by it.)

66. Water is sexy. (I want to be near it, to be in it, to move through it, to be under it. I want it in me.)

I smiled. Not long after, I forgot about the photos and their captions, just as I stopped thinking about about my time as a lifeguard. Even when McCarren Pool opened last month, I didn't think about the water as anything more than an afternoon's diversion.

• • • •

Back when I was a lifeguard, I had always kept an eye on the evening swim teams practicing. After a shift, I sometimes jumped straight from my chair into the water and started swimming laps beside them. I swam to shake off the heat and restlessness of the long day, to bring my mind back to the real world I would face upon exiting the water. Watching those swimmers, I wondered what they thought about as they went from one end of the pool to the other. And then I read Leanne Shapton’s Swimming Studies.

I know their hours of swimming are no less repetitive than a lifeguard’s on his chair. Instead of focusing on everyone but themselves, however, swimmers focus on nobody but themselves. Leanne Shapton distills this to a state of mind.*

I swim a few laps, then decide to do a hundred. This is my default workout, one hundred reps of whatever. One hundred is actually not much, but it sounds nice, like “an hour,” even though swimming a hundred laps of this short a pool does not take an hour, it takes about twenty minutes ... As I swim, my mind wanders. I talk to myself. What I can see through my goggles is boring and foggy, the same view lap by lap. Mundane, unrelated memories flash up vividly and randomly, a slide show of shuffling thoughts.

Leanne had been training for the Olympics. She nearly qualified, but didn’t. I wasn’t interested in reading about this, nor she in writing about this. Instead, I read about the small, quotidian details of a swimmer's life. Her drives with her parents to and from the pool. The effects chlorine has on swimmers’ swimsuits, on swimmers’ hair. And then there are her watercolors. She continually detailed the contours of the different pools she had gone to—a silly thing to mention, I thought, until I came much later in the book to watercolors of all the swimming pools she remembered, and I suddenly recognized the details she had described.

Leanne stopped seriously competing after those Olympic trials, channeling her energy into art. The result, in Swimming Studies, is a collage of prose texts and pieces of art that cumulatively feel well, watery. Aqueous. The quality of her diction, as well as the similarity of the many scenes she depicts, makes reading the book feel very much like swimming laps with someone who knows the pool, the water, and her own body, extraordinarily well.

• • • •

I was a lifeguard. And Leanne, the one in the water, was just as obsessed with its surface. She went through rubber swimming caps, through championships, through boyfriends and houses and cities, and still relished each moment she made the first dive into the sickly-blue water. I looked through the footnotes about her swimsuits, and was reminded again of Roni Horn’s pictures.

Sure enough, those photographs had been made into a book: Another Water (The River Thames, for Example). Roni's footnotes were still as idiosyncratic and meditative as back at the Whitney.

411. Water shines. Water shimmers. Water glows. Water glimmers. Water glitters. Water gleams. Water glistens. Water glints. Water twinkles. Water sparkles. Water blinks. Water winks. Water waves.

412. Under the cover of harsh, elusive colors, black is constant. These useless, hopeless colors gather around this black place.

413. The Thames is a tunnel.

414. The river is a tunnel, it’s civic infrastructure.

415. The river is a tunnel with an uncountable number of entrances.

416. When you go into the river you discover a new entrance—and in yourself you uncover an exit, an unseen exit, your exit. (You brought it with you.)

There are many waters, but our experiences with them were deeply similar, deeply meditative. I looked up from each to realize that I did not smell chlorine. I was not in a lifeguard chair in the Midwest or in Brooklyn but on a couch in my apartment. These books had so perfectly recreated in my mind the experience of sitting at the edge of water that those faraway summers had come back and, doing flip turns, splashed me awake.

* Buzz Poole, who also works at Black Balloon and was once a competitive swimmer, has a wholly different and very enjoyable perspective on Shapton's book at The Millions.

Image credit: David Hockney, Swimming Pool Lithograph,ahholeahhole.blogspot.com

Sheila Heti came from Toronto to New York this week, ready to launch her "novel from life" How Should a Person Be? in the States. I’m a fanboy, so of course I was there at the Powerhouse Arena on Tuesday night.

Two weeks ago, I had pushed a copy of the book into my friend’s hands. “You’ll get a kick out of it,” I insisted. A week later, she told me she had a clear picture of the characters: she was positive that the narrator, also named Sheila, was a tall woman with flowing, curly hair—the kind of woman who effortlessly pulls off a feather boa. And Margaux, her best friend (also the book's dedicatee), had to be blonde, with a clean-cut face and an understated, artsy style.

Well, not quite. A quick Google search led to this picture, with Margaux Williamson on the left, and Sheila Heti on the right. Sheila had put a version of herself in How Should a Person Be?, but it wasn’t quite the same as the woman who stood in front of us Tuesday night.

“Yeah, I sort of forgot to describe myself,” she said when we mentioned the discrepancy. Then she looked down and signed my book.

Did it bother her?

“No, I’m not the person I put in the book. That was a different time.”

Hmm. Would Margaux be upset if we asked her to sign the book? (Margaux has not always been the nicest friend.)

“Margaux? She’d love it!”

We went over to Margaux, who was surrounded by an adoring crowd. We opened our books to the dedication page and handed them over. She couldn’t stop smiling as she scribbled our names and her signature.

We couldn’t believe ourselves. It was like seeing the cast of The Hills in the flesh. They were actually real? Wearing the same kind of clothes we did? And signing our books, even though they’d fought about their lives being recorded?

Cool.

••••

A couple of months ago, I’d gone to a different bookstore to see John D’Agata and Jim Fingal talk about their own relationship, recorded in The Lifespan of a Fact. These were two men who had argued over most of the facts in an essay that was later turned into the book About a Mountain.

“Wow, Jim, your penis must be so much bigger than mine,” John D’Agata spouts off sarcastically in one part of the book. “Your job is to fact-check me, Jim, not my subjects.”

As it turns out, quite a bit of this dialogue had been made up. This knowledge didn’t endear me to the idea of meeting a self-absorbed artiste (D’Agata) and a battle-scarred fact-checker (Fingal). These were the characters they’d made out of themselves, after all.

Then the two men walked to the front of the room.

John D’Agata is actually extremely nice, even apologetic—one minute ofthis video shows how transparent his emotions are. I was astonished at the vehemence of my fellow audience members. “Can’t you understand that you shouldn’t present distorted facts as journalism?” they asked.

No, John D’Agata explained in an apologetic way, he wasn’t writing journalism. An essay was a completely different thing.

He seemed surprised at the monstrous caricature he’d created of himself. Jim Fingal found the whole setup rather amusing. I looked around nervously for tomatoes about to be thrown. These two writers had become victims of their own inventions.

••••

Did either pair of authors owe it to their readers to present an accurate picture of themselves? What transformation was permissible in art, if these books were supposed to be “nonfiction” or “a novel from life”? Was I right or wrong to be surprised by the people behind the characters?

I had read about these characters, but seeing the authors left me wondering: How should a person be?

image credits: velvetroper.com; torontoist.com

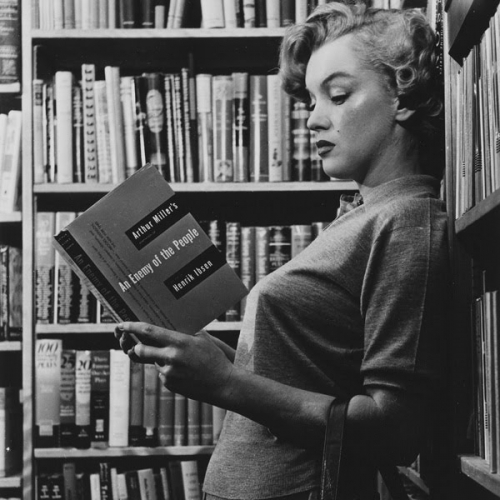

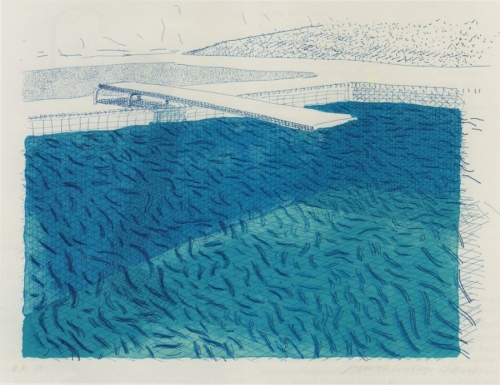

The statistics are in! Thanks to the VIDA Count, there's fresh proof that we live in a world of crappy exclusion in the books department. While I was happy to come across an article in the Irish Times about a retired High Court judge urging lawyers and judges to read great works of literature, I was made profoundly less happy by recent reports on gender and racial bias in publishing. And then I figured it all out: what the judge and the reports suggest to me is a need for empathy, and a need for more people to desire an experience of empathy.

The judge, Bryan McMahon, said that "[l]awyers should be acquainted with great literature and should learn from it. It deals with envy, jealousy, greed, love, mercy, power politics, justice, social order, punishment ... Judging also involves the soft side of the brain, dealing with compassion, understanding, imagining the extent of one’s decision.” Literature has the capacity to peel us away from the world we think we know and take us into an entirely new experience with a changed perspective. This is useful not just as an escape or to serve as some kind of refreshment; books complicate and deepen our understanding of the human experience.

So what happens when almost all of the books that are promoted and discussed in major outlets derive from a largely homogenous pool? Does this limit our access to the great variety of human experience? Could this mean—because of stuff like profitability and basic self-interest—that publishers and reviewers mostly promote the human experience that reflects theirs?

I don’t wish to come off as a big poopy diaper, but in light of the statistics showing that high-visibility literature is mostly male and most definitely white, I think it’s valuable to note that publishing is often a gross machine and often doesn’t reflect very good taste or wise choices. But as much as the nasty, naughty publishing machine is a total idiot with no gumption or integrity, I’d also like to suggest that there could be a fair amount of readers (yeah, the white ones with the money) that don’t much like that which is unfamiliar to them. Readers can just as guiltily say that they want to read a book “they can relate to.” Somehow fifteen dollars has become too precious an amount to spend on something so unnecessary as literature, but 99 cents to download some "guaranteed" blockbuster is a great modern thing.

Think of how the majority of book buyers find books these days. Amazon tells you what other people liked based on what you like. How could this possibly lead to a diverse reading experience?

To top it off, the attachment to indulgence and self-interest is rampant to the point of perversion in this country. I don’t have all my statistics in on this, but I’m fairly certain. And when the self is held as the utmost importance, how could anything of quality be read at all? Does no one want to take a risk or try something new? Maybe readers would enjoy different books if publishers and reviewers spent a little more time pushing different good books and not just the guaranteed sellers for an already established (and at this point, hopefully bored) audience.

image: vidaweb.org

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©