I remember my first Tom Waits song, "Tom Traubert's Blues," like the first time I was racked by a girl in middle school. [Rack: v. To kick or knee one in the balls, in Texas. -ed] Not fondly, but viscerally. His voice ruptured that which I was accustomed to hearing. Unlike the kick to the crotch, however, I wanted more. There was something intimidating, yet soothing, about his raw and caustic soul. The “brawlers, bawlers, and bastards” Waits sings about can haunt you.

Bad As Me is no exception. In many ways a microcosm of Waits’ entire oeuvre, his new album traverses gritty up-tempo train-chugging blues (“Chicago”), Elvis-like swagger (“Get Lost”), barroom bravado (“Bad As Me”), and existential angst (“Last Leaf”). Its varied musical portraits reflect the diverse personas that populate our culture: the ruined life of a recent war vet (“Hell Broke Luce”), addiction (“New Year’s Eve”), and the white noise of domesticity (“Talking At the Same Time”). A gallery of misfits and anti-heroes, all of them desperate, broken, and searching.

“Pay Me,” a song about the misery of an aspiring actress-cum-dancer, is the album's emotional nucleus, pulling together some of its key themes: the quest for, and question of, home; the irony of redemption; fatalism tinged with a fuck-you smirk. The song is starkly furnished with guitars, strings, accordion, and piano, allowing Waits to mourn, his voice hushed and fatigued. As usual, he's a brilliant storyteller:

You know I gave it all up for the stage

They fill my cup up in the cage

It’s nobody’s business but mine when I’m low

To hold yourself up is not a crime here you know

At the end of the world.

Like us, Waits’ characters are full of delusions and contradictions. We simultaneously long for and shun that which is impossible to reach (“home,” for example). In this way, “Pay Me” closes ambiguously, juxtaposing fate and hope.

And though all roads will not lead you home my girl

All roads lead to the end of the world

I sewed a little luck up in the hem of my gown

The only way down from the gallows is to swing.

But in the final coda, resignation is mitigated by that fuck-you smirk: “And I’ll wear boots instead of high heels/And the next stage that I am on it will have wheels.” Nodénouement in a Waits song is ever simple or one-dimensional.

I still find Waits intimidating, his stories haunting. But I’m learning to accept and embrace his brawlers, bawlers, and bastards. After all, these are stories about us.

Photo: For the Sake of the Song

Beyoncé's video for "Countdown" has got me wondering: when did eye spasms, epileptic winks, vertiginous whatever-rolls and hummingbird blinks become the new voguing? Are hyphy eyes the next big thing?

Read More

Outside of a town called Homer, NY, we put on the new Wilco album. "We" is me and three others, two of whom are Australian. We started playing together early this year. We’re aiming a rented Toyota minivan at Toronto, where we’ll play later tonight. Tomorrow we’ll drive this same highway, passing Homer in the other direction, smuggling only our hangovers and tinnitus back home.

Read More

Previously in this series, James listened to Wilco’s The Whole Love en route to a show in Toronto. We join him now on his way home.

Back on American soil. Shattered, thanks to an all-night speakeasy that a waiter at our show had told us about. I had refused to sit out any rounds, even though the guy buying them, our singer, is six inches taller than I am and Australian. This same singer, totally unaffected by the vats of lager he'd ingested on the other side of dawn and the Canada-America border, puts on Feist’s new album, Metals.

It begins quietly, which is good. I had put on the Descendents’ ALL as we pulled out of Toronto, but that only added to my suspicion that someone had stuck a pushpin through my left eyebrow while I slept.

“Bring ‘em all back to life,” she chants in the second song, even more lowdown than the first. I start thinking back to Feist’s breakout year. LikeYankee Hotel Foxtrot, The Reminder was absorbed by most of us simply by having been alive at the time of its release. Shops, apartments and TV networks all seemed to play it on a loop. For a little while, it was the score to everything.

So I’m surprised to find Metals serving up one dirge after another. Feist’s voice could make a Burzum song buoyant, but here she’s surrounded it with thundering toms, plodding horns, and guitars as stark as PJ Harvey’s on To Bring You My Love. In fact, Harvey’s spooky middle years hang over the whole album. I love that sound, but maybe it’s best experienced at night, in one’s room. Not so much in a van that keeps passing red barns, silos, and...were those llamas?

Metals could function as a flawless makeout album—with two exceptions. The chorus of “A Commotion” sounds like Agnostic Front had wandered into the vocal booth; and “Undiscovered First” lurches into a growling, stomping waltz. Otherwise, the resolutely doleful mood has the guys up front calling out, “Change gears, Feist.”

The album ends—“Get it right, get it right, get it right”—and our drummer puts on Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, a learning curve-free album if ever there was one. Metals will take some time, but it’s time I’m willing to spend (ideally without the accompaniment of a skull-cracking hangover)—time, I’m sure, many of us will invest, once we accept that this particular followup is morePinkerton than Neon Bible. Feist has years to create the work that synthesizes Metals and “My Moon.”

Photo: faceook.com/feist

Wife: “Can we please listen to something else?!”

Me: “I thought you didn’t care.”

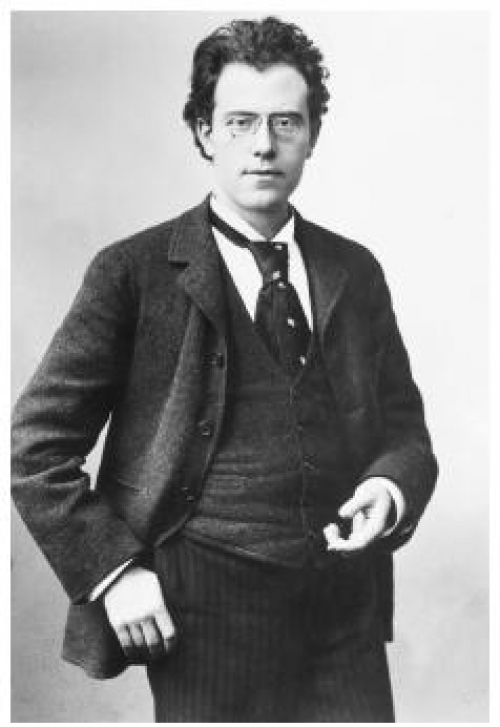

Wife: “ENOUGH FUCKING MAHLER!”

And with that the Adagio of Mahler’s Ninth—one of the most achingly desperate representations of human frailty and mortality in music—is abruptly replaced by the thyroid-thumping throb of Lady Gaga.

Wife (singing): “‘Rah-rah-ah-ah-ah-ah! Roma-roma-maaa!’”

Me: “I got it.”

Wife: Gaga just made Mahler her BITCH!!”

It’s too early for this. I leave the room, put on my sneakers, and head out for a morning run.

I’ve been listening to a lot of Mahler recently because 2011 marks the centennial of his death. Last year marked the sesquicentennial of the composer’s birth, thereby unleashing two-plus years of geeked-out Mahler hysteria. Orchestras around the world have dedicated multiple concerts to perform Mahler’s works. Special edition box-sets have been issued. Coins have been minted. And many articles, books, and DVDs issued. Along with my fellow deranged Mahlerians, I’ve been blissfully immersed in at all.

Of all that I’ve read about Mahler and his music recently one biographical quirk has been a source of continuing fascination: his estranged brother, Alois, who moved to Chicago sometime in the early 1900s. Essentially disowned by Gustav and his other siblings, Alois moved to the U.S. to begin life anew (he also changed his name to Hans). While little is known about Alois’ American life (he died in 1931), his final address in Chicago, 3931 North Hoyne, is a mere 5 blocks from my house.

Now, on my early morning runs, I will occasionally run past Alois’ old house, in an odd sort of homage to his famous brother and imagine who Alois was and what, if anything, he thought of his brother’s music. Did Alois attend the debut of his Gustav’s music (Fifth Symphony) in Chicago in 1907, or the performance of the Eighth in 1917? Did Alois mourn Gustav’s death in 1911?

Alois’ old house has also become a touchstone of sorts for my own reflections on Gustav’s life, family, and music: How does Mahler’s music reflect his relationships with others? Is Theodor Adorno right that Mahler’s music traces “the history of a breaking heart”?

I believe my polite historical stalking symbolizes a search for a deeper, nuanced, more personal connection with Mahler’s music—a subterranean attempt at exposing the unexposed, of yearning to identify the invisible and forgotten next to the canonized and memorialized, and thereby striving to humanize one man’s music.

Or at least that’s what I tell myself as I run past a stranger’s house at 6:00AM.

(Photo: Corbis)

Late last month, the Brooklyn-based band Milagres celebrated the release of their second album, Glowing Mouth (Kill Rock Stars), with a Mercury Lounge show. Keyboards and a drum pad lined the front of the stage; on the far sides, the guitarist and bassist juggled axes, tech, and tambos.

Read More

So I heard from a fellow blogger that you guys are opening a burger joint outside of Boston. Congratulations.

Read More

As you may have seen, the indie-cum-mainstream rock outfit the Decemberists recently partnered with Michael Schur to make a video for the band’s “Calamity Song” based on the Eschaton throwdown scene from Infinite Jest, in which the Enfield Tennis Academy’s younger students enact—with tennis rackets & 5 megaton tennis balls—the thermonuclear self-destruction of the modern world before it all collapses into a “degenerative chaos” of punching, tackling, barfing…and a head smashed through a computer monitor.

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©