I just dug up my copy of The Great Gatsby, full of my highlighting and marginalia from junior year. I can’t think of a friend who didn’t read it for American Lit in high school, and I’ve only met one person who didn't love its clarity and beauty. I looked at the dedication: “Once again to Zelda.” But the epigraph took me by surprise.

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

—Thomas Parke D’Invilliers

Plenty of books have interesting epigraphs, as Kayla recently pointed out, but I couldn’t believe I had missed this one completely. The poem’s inclusion does make sense, I suppose: the whole book is about self-interested characters trying to charm each other. And there’s a visible shift across the novel from Gatsby’s aloofness, with his showy library (“Knew when to stop too—didn’t cut the pages,” a guest at one of his parties declares), all the way to his final, embarrassingly honest determination to “fix everything the way it was” in order to woo Daisy once more. So the D’Invilliers quotation is a fitting epigraph—another green light leading Gatsby on.

But then I decided to look up Thomas Parke D’Invilliers, figuring he was a nineteenth-century author or a British dignitary. I was wrong. D’Invilliers is a pseudonym for Fitzgerald himself. I was struck by this subtle trick. A pseudonymous epigraph per se isn't all that dishonest, but F. Scott could just as easily have left it unsigned. The same name had surfaced in This Side of Paradise, actually: in that case, D’Invilliers was a stand-in for F. Scott's friend, John Peale Bishop, and in the novel he was an aspiring poet. In real life, as is implied in The Great Gatsby's placing his pseudonym next to several lines of verse, he became an accomplished poet.

But the line's been blurred here: is the Thomas Parke D'Invilliers of the epigraph supposed to refer to John Peale Bishop or Fitzgerald himself? If the author had chosen to call his masterwork Gold-Hatted Gatsby or The High-Bouncing Lover, this question might have been an even more significant one. As it is, it reads like a fumbling attempt on the author's part to erase his presence in the book.

Nick says of himself, “I am one of the few honest people I have ever known.” I didn't always buy that Nick was a fully reliable narrator, given the way he often withheld information from me. So I wonder: if Fitzgerald has been playing with truth from that prefatory page of the book, what else has remained buried under his words, undermining or contradicting the seemingly straight trajectory of his story? Few interpretations of The Great Gatsby have succeeded in aligning F. Scott Fitzgerald with any of the characters within, so why does a trace of him linger here? And if Nick is a liar by virtue of his author's manipulations, then how much has he, as a narrator, been hiding from us about the American Dream?

There are few things in contemporary pop culture that elicit my fight-or-flight instincts more acutely than My Little Pony and dubstep. Yet Jason Kottke's thorough followup to a New York Times correction—which had misnamed a particular Pony character—magnified my worst grade-school fears by combining the two. Apparently, there exists this horrifying, fist-pumping subgenre called "dubtrot," i.e. My Little Pony dubstep remixes. The sadomasochist in me just had to investigate further.

My Little Pony—specifically My Little Pony: The Movie—tarnished my childhood. The trouble began with an absolutely frightening film poster, depicting this purple ooze monster called The Smooze attacking the Ponies' Dream Castle. Stay with me here. Though I was young, I distinctly remember being coerced into the theater by my sister. Visions of surly, singing ooze consumed my dreams that night. By age 10, I was readingFangoria.

I rewatched My Little Pony: The Movie to see if it carried the same shock value as it had two decades' prior. A: no. The Ponies—with names like Lickety-Split or Shady, denoted by the ice-cream cone or sunglass tattoos on their respective asses—hurl rainbows (though not unicorn poop) at the evil ooze, saving their kingdom. Hell, Danny DeVito gets lead credit, voicing the Grundle King (choice quote: "I try not ta mention it too often! Witches! Smooze! It was terribuhl!"). Granted, De Laurentiis Entertainment Group distributed Maximum Overdrive and Blue Velvet the same year. And that sequence when the witches are rowing a pantaloons-propelled skiff over waves of Smooze, singing "Nothing Can Stop the Smooze" to a barbershop-style chorus…that's still creepily upbeat.

Speaking of creepily upbeat, let's talk "dubtrot." Kottke mentions "Rainbowstep," which I guess is a good primer for newbies. It's a Youtube clip, a blessing and curse to the post-MTV generation, as we get strobey visuals with the seismic beats and chirpy Pony dialogue. "Cuz Dubstep with Rainbows is 20% Cooler!!! XD" writes uploader—and purported My Little Pony fanboy "brony"—ZestyArt, crediting the track (or its inspiration/style?) to Skrillex, dubstep's macho-ass posterboy. Now me, I'm in crooner/producer James Blake's camp, thanks in no small part to my NYC muse's insistence. One might "dub" Blake's enveloping atmospherics as post-dubstep, but if he calls out Skrillex's antics "without naming him," then I'm taking Blake's side.

Frat boys killed big beat, so it's no shocker those same meatheads took to Skrillex's inelegant steroidal “brostep” like Flutter Ponies to glitter. I can't credit Skrillex for dubtrot's saccharine ear-trauma (he'd sooner produceKorn's new album), and I love me some bass, like Richie Hawtin's classically ferocious live sets, replete with viscera-rearranging throbs and mind-splintering breaks.

Still, Hawtin throwing some credibility at Skrillex's Mickey Mouse beats makes me a bit vexed. The former screamo kid ain't even good enough for the bronies.

Image: DubTrot's SoundCloud avatar

A New York Times review of Would It Kill You To Stop Doing That?, a new book on manners by Henry Alford, got me thinking about how much of my social grace I’ve gleaned from works of fiction. Beyond the more obvious social dramas of Austen or Fitzgerald, books can provide useful advice on how to act in certain situations—and warn of the consequences when certain behaviors are found undesirable.

I figured, if James could look to literature to gain a little perspective on zoophiles, I could consult the bookshelf to learn how to behave. What follows is a brief guide to help you get started.

- All little children should be given Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Sure, it’s a little violent, but unimaginable horror never killed an eight year-old. The lesson here is embodied in the boy: at the end of days, walking around starving, the little guy hardly ever complains (or talks, for that matter), and he's spectacularly polite and loving towards his father. Does your kid whine about not getting the candy cereal at the grocery store? Hand him or her a copy. Maybe read it at night before they go to bed. See what happens.

- Do you know any sexual deviants who just need to shut up about it already? Give them a copy of Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior. One of the beauties of Gaitskill’s short stories is how remarkably calm everybody is about how messed up their sex is. As uncomfortable and sometimes harmful as her characters can be, Gaitskill narrates in a way that shuts down all the annoying, gossipy shock value and allows the perverts to be precisely what they are: just humans.

- Even though it was published way back in 1962, I think Another Country by James Baldwin should be handed out to every white, liberal-leaning heterosexual along with their organic oats and fair trade coffee. Have you ever referred to someone else’s partner as their "roommate"? Do you decorate with the aim of exhibiting your knowledge of cultural difference? Maybe you’re super well-intentioned but don’t understand what all the fuss is about. Mr. Baldwin can tell you.

- Is there anything worse than the plethora of man-children running around today? Guys in their twenties and thirties shirking the responsibilities of career, family, haircuts, bathing. Maybe it’s time for a good look at one of the prototypes of the modern man-child: Rabbit, Run by John Updike. The book should be read not to shore up men's juvenile mindsets, but to show them that their very special feelings of entrapment and angst are anything but new. Besides, until you can narrate your life at the level of Updike’s prose, your angst won’t even get you any attention.

But the best reason to pick up a book of fiction? It might not even be the wisdom between the covers, but that your chances of fucking up decrease if your nose is stuck in one.

Image: tylershields.com

Jesse Bering’s recent Slate article “Porky Pig” is a shocking, hilarious, and ultimately brave look at the stranger-than-fiction world of zoophilia. This line says it all: “For most people, it’s an icky conversation to have—I do wish my dog would stop staring at me as I’m typing this—but queasiness doesn’t negate reason.”

Read More

Would-be roman-fleuve writers: don't equate quaffing as much coffee as Honoré de Balzac with prolific yields. For the father of the naturalist novel, regular 15-hour stints fueled by that blessed brew still weren't sufficient to finish his multi-volume magnum opus La Comédie humane. Though in Balzac's defense, he did complete some 91 works, like the charmingly titledL'envers de l'histoire contemporaine, aka The Seamy Side of History.

Hear caffeine's effects from Balzac himself: "Ideas quick-march into motion like battalions of a grand army to its legendary fighting ground, and the battle rages. Memories charge in, bright flags on high; the cavalry of metaphor deploys with a magnificent gallop; the artillery of logic rushes up with clattering wagons and cartridges ... the paper is spread with ink — for the nightly labor begins and ends with torrents of this black water, as a battle opens and concludes with black powder."

My pulse raced just reading that. Mind you, I grew up around Houston, TX, land of purple drank, at the psychoactive spectrum's extreme opposite end. I achieved some of my best writing as a freshman at the University of Texas, when a semester-spanning head cold meant daily draughts of Dimetapp. While I wasn't sippin' on some syzzurp beyond the prescribed dosage, the dextromethorphan did wonders for my Japanese Ghost Stories papers. I forewent speaking in class (thanks to dex's dissociative effects), but my ambrosial deciphering of selections from Kwaidan and Ugetsu prompted my predilection for J-Horror.

I was a ubiquitous presence at the 24-hour coffeehouse near campus. I didn't share Balzac's focused work ethic and caffeine tolerance, though I subsisted nights on "hammerheads"—the cafe's name for a pint glass of black coffee with two shots of espresso, like a nerve-rattling sake bomb—and secondhand smoke, while writing on Italian modernist cinema.

Now absinthe, that's an addiction I'd like to claim. Here in NYC, I frequented White Star, mixmaster Sasha Petraske's former brick-lined corridor down on Essex Street. I'd chase la fée verte while negotiating my art-critique notes. It was like my own Midnight in Paris, but what impressionable young romantics haven't imagined themselves within fin de siècle Paris?

I've never attended a gallery opening under the influence of absinthe. Though it's quite clear art and excessive booze don't well mix. Nor have I been bothered to procure my own absinthiana accoutrements to serve it at home (that spigot fountain, the Pontarlier reservoir glasses, the damn slotted spoons). I suppose a bottle of Kübler Superieure might suffice, but for me—an aficionado if not a total addict—the preparation ritual is as important as the enduring round-edged buzz.

Photo: composite image of Big Moe and Honoré de Balzac, culled from Wikipedia and Photo-chopped by the author

Some folks make New Years resolutions to drink less and exercise more. This year, I’ve resolved to write better marginalia in the books I read.

In the December 30 issue of the New York Times Magazine, Sam Anderson offers a sampling of his marginalia from some of the books he read in 2011. I admire Anderson for this—it’s like peeking inside another’s intellect and imagination. And his article inspired me to take a closer look at what I write (or don’t write) in the books I read.

I am currently reading Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Which means Dostoevsky’s text is being slowly invaded by my own jottings. I underline, I circle, I draw arrows to connect specific words and phrases, I use exclamation marks to highlight passages I like and large Xs to cross out phrases or plot developments I find obnoxious. And like Anderson, I’m a chronic margin scribbler.

Sometimes my comments are of the ordinary roadmap variety (page 31: “Note importance of physiognomies in D’s descriptions”). Other times, they might point out parallels with other characters/works (page 227: “Note similarities to Raskolnikov’s wandering in C&P) or try to draw out the philosophical depths of Dostoevsky’s story (page 226: “pre-epileptic epiphanic illumination --> higher existence --> fleeting --> sublime moments of infinite clarity and understanding accompanied by suffering”). These notes aren’t intended for some greater end or project (although, come to think of it, it would be interesting to trace the meaning, use, and development of human “strain” throughout Dostoevsky’s novels); they simply represent my brief thoughts and reflections. They help keep me engaged while I read.

Unfortunately, however, I’m a hyper-self-conscious marginalia writer. I dwell too much over the right words, worry too much about trying to express an exact thought. Perhaps I’m also worried about what others might think if they read my scribblings. What if, after I died, a friend came across my marked-up copy of The Idiot? “Why the hell did he write that?" this friend would say. "That wasn’t what Dostoevsky was going for at all! I didn’t know Todd was such a simpleton.” But marginalia ought not be an art of perfection. It should be an informal stream-of-consciousness dialogue with the text. As Rachel recently blogged, marginalia makes reading more participatory and performative.

So as I wrap up The Idiot and begin re-reading The Brothers Karamazov, I’m resolved to become a less self-conscious and more expressive scrawler. Here’s to a 2012 filled with better marginalia.

Photo: Author

The flight from Los Angeles to Honolulu takes almost six hours, so when I went with my family a few years ago, Swann’s Way went into my carry-on.

Days later, deep in the book, I wondered: What if Proust was Hawaiian? An aging man with an aloha-print shirt eating chocolate-covered macadamia nuts and lying in a cork-lined room to write his masterpiece set in France? And what do Proust’s Hawaiian readers make of his book? If authors can be surprised and even delighted at their readers’ various and unexpected readings of their novels, then I’m inclined to believe that each reader creates an personal canon and reacts to specific works of literature wholly in light of what she or he has read before.

Proust’s A Remembrance of Things Past can be, and often has been, reduced to narrow contexts. It’s been treated as an overtly French work; it’s so easy to relish the names of specific cities and particular French customs. This certainly can be part of Proust’s appeal—the book covers I’ve seen have practically cried out, Pick up the book! I’m sophisticated and glamorous and French!—but to read it as a French souvenir makes the book deeply foreign. Even the different translations reflect this—the more literal translation, In Search of Lost Time, offers a far less dreamy perspective on the French text.

Or there’s the autobiographical reading (did the author really have to name his narrator Marcel?), which could structure the text into “fictional” and “non-fictional” sections.

The tropics revealed a great deal in Proust’s text that the man never would have envisioned. Proust critiques French aristocracy though the Duc de Guermantes’s vulgarities, and Hawaiian readers might well find a parallel to the disdainful divide between Hawaiian natives and non-natives, but the not-particularly-hierarchal relationship between those two segments of Hawaiian society certainly reframes Marcel’s role as an impertinent social critic. Marcel’s weaknesses of memory become both a metaphor and an indictment of Hawaiian culture’s unintentional failure to fully account for historical truth. And when I came across a mention of the high price of quality goods in France, I looked out the window and saw the bewildering price of gas on the island.

I’ve only touched on what might come to light if we looked at A Remembrance of Things Past from the wrong end of a Hawaiian telescope. This is the first in a series of (mis)readings, which will range from considering Victorian literature’s response to AIDS to how Crime and Punishment could be understood if it turned out to have been written by Borges. Keep your eyes peeled, and don’t hesitate to suggest your own (mis)readings in the comments.

Image: aquawaikikiwave.com

I'd nearly completed reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in Japanese when I found this impressive "liveblog" of Haruki Murakami's magnum opus1Q84 on Daniel Morales' site howtojapanese.com. Oh yeah, I thought, I need to get on this. In September 2009, I picked up the first two volumes of1Q84 (volume three was published in Japan in April 2010) and made it my goal to tackle 'em. I noted the English translation wouldn't be out until fall 2011. What the hell, I'll read and translate!

The translation was arduous, funny at times and painful in others. Example: spending ten minutes chipping away at a paragraph, cringing as 睾丸(testicles) gave way to 蹴る (to kick). Another recurring hiccup was Murakami's aforementioned pop culture name-dropping, peppering the text with names like バーニー・ビガード (jazz clarinetist Albany Leon "Barney" Bigard) and トラミー・ヤング (trombonist James "Trummy" Young). I have a newfound appreciation for Louis Armstrong's All-Stars. Plus, I learned tons of vocabulary, which helped hugely in my coursework at the Japan Society (and hopefully impressed some girls). Translating forced me to read1Q84 slowly, savoring each surreal, mundane or salacious passage. It also ensured a very personal way of understanding Murakami's text.

When The New Yorker ran an excerpt from 1Q84 in early September 2011, nearly two months ahead of its English publication, I felt oddly wary. It was "Town of Cats," originally Chapter 8 of Book 2 (and over 700 pages deep) in the Japanese text. Murakami calls this place and its namesake in-text fable 「猫の町」, which I worded as "Cat Town." Now it's in print as "Town of Cats." I suppose both "sound" like a fable, but this simple incongruity didn't sit too well with me. I read "Town of Cats," enjoyed it overall, but now awaited the English publication guardedly.

So guardedly that I've yet to read fully the English 1Q84, translated by Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel. I've spent hours flipping through the pages, remarking on its considerable heft and Chip Kidd's awesome design. But those bits I was worried about? Here's my take on an early passage, from Chapter 1 of Book 1:

Aomame inhaled deeply and then exhaled. She then climbed over the railing while continuing to chase the melody of "Billie Jean" in her ears. Her miniskirt rolled up over her hips. "Who cares!" she thought. If they want to look, let them look. It's not like they're going to see what kind of person I am just from seeing under my skirt. Besides, her firm, alluring legs were the part of Aomame's body that she was most proud.

And the official translation:

Aomame took in a long, deep breath, and slowly let it out. Then, to the tune of "Billie Jean", she swung her leg over the metal barrier. Her miniskirt rode up to her hips. Who gives a damn? Let them look all they want. Seeing what's under my skirt doesn't let them really see me as a person. Besides, her legs were the part of her body Aomame was the most proud.

Incidentally, I didn't add that "firm, alluring" part: that's in the original. It's the little rhythmic jazz, like "railing" vs. "metal barrier", "chase the melody" vs. "to the tune"—inherent in Murakami's words—that's missing in the official translation.

Murakami's classic weirdo teenage girl here is ふかえり, which for language students is written entirely in hiragana (like long-form Japanese script, often seen in some degree in women's proper names). It's her nom de plume, a takeoff from her real name 深田絵里子, or Fukada Eriko. I translated it as Fukaeri, running the sounds together rather mellifluously. That's how it would sound in Japanese! Nope: in English 1Q84, it's Fuka-Eri, overemphasizing that fact she's contracted her given and family names together.

Also: how Fukaeri/Fuka-Eri speaks. Murakami emphasizes her flat, laconic tone by writing her dialogue in only in hiragana/katakana, the two syllabic Japanese writing systems, versus intermingling them with kanji. Here's my version of one of her exchanges with Tengo (the second major protagonist, one of Murakami's most classic thirtyish, slightly clueless males):

"You know me?" Tengo said.

"you teach math"

Tengo assented. "That's right."

"i've heard you twice"

"My lecture?"

"yeah"

There was something peculiar about her way of speaking. Her sentences were scraped of embellishment, and there was a chronic lack of accent, limited (or at least presenting that limited impression to others) vocabulary. Like Komatsu had said, certainly odd.

And the official translation:

"You know me?" Tengo said.

"You teach math."

He nodded. "I do."

"I heard you twice."

"My lectures?"

"Yes."

Her style of speaking had some distinguishing characteristics: sentences shorn of embellishment, a chronic shortage of inflection, a limited vocabulary (or at least what seemed like a limited vocabulary). Komatsu was right: it was odd.

This girl speaks, like, teenage-angsty cool. Even changing that trite "yeah" into a "yes" feels a bit polite. Murakami has a history of writing characters with unusual ways of speaking, like the Sheep Man in Dance, Dance, Dance(depicted in English conversing in long run-on phrases), the plucky old scientist in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (hillbilly accent), and old savant Nakata in Kafka on the Shore (simple English, even simpler than Fukaeri/Fuka-Eri). But how much of their conversational quirkiness makes it into the English?

It's not totally surprising I feel so strongly about my first Haruki Murakami novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, which I read in English, and reading1Q84 entirely in Japanese ahead of its English translation. I can practically recite from memory passages from both, and though I'm pleased to have read ねじまき鳥クロニクル belatedly in Japanese, Rubin's English text will forever remain close. I'm sure I will come around to fully reading the Rubin/Gabriel translation of 1Q84, though I'll be unable to shake the notion that what I'm reading is just their interpretation.

Photo: Mr. Fee

A few fun-facts about Haruki Murakami, Japan's most celebrated contemporary author and the man behind the year-end publishing sensation1Q84: he name-drops classical études as frequently as 20th century jazz and rock greats; he once ran a coffeehouse-jazz bar in Tokyo; and he's a triathlete. The man is a well-rounded badass.

I knew little of Murakami when I began reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—some six hundred pages of potent modern-day Surrealism—back in university. Jay Rubin, one of his three longtime translators, handled the English edition, a necessary thing for me then as a just-budding student of Japanese. In addition to the silky prose, I was enraptured by the directness of dialogue and description despite Murakami's continual bending of reality.

I compared Rubin's translation with an earlier one by Alfred Birnbaum, who'd translated the first chapter of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle as The Wind-Up Bird and Tuesday's Women (it originally ran in The New Yorkerseveral years prior but reappeared in the short story collection The Elephant Vanishes), and instantly sided with Rubin. The interplay between Murakami's classic thirtyish male protagonist, Toru Okada, and the author's equally classic weirdo teenage girl, May Kasahara, just felt better in Rubin's words:

Strange, the girl's voice sounded completely different, depending on whether my eyes were open or closed.

"Can I talk? I'll keep real quiet, and you don't have to answer. You can even fall asleep. I don't mind."

"OK," I said.

"When people die, it's so neat."

Her mouth was next to my ear now, so the words worked their way inside me along with her warm, moist breath.

"Why's that?" I asked.

She put a finger on my lips as if to seal them.

"No questions," she said. "And don't open your eyes. OK?"

My nod was as small as her voice.

She took her finger from my lips and placed it on my wrist.

Compare that with Birnbaum's earlier translation. That directness, that humidity-induced curtness, is lost:

Strange, I think, the girl's voice with my eyes closed sounds completely different from her voice with my eyes open. What's come over me? This has never happened to me before.

"Can I talk some?" the girl asks. "I'll be real quiet. You don't have to answer, you can even fall right asleep at any time."

"Sure," I say.

"Death. People dying. It's all so fascinating," the girl begins.

She's whispering right by my ear, so the words enter my body in a warm, moist stream of breath.

"How's that?" I ask.

The girl places a one-finger seal over my lips.

"No questions," she says. "I don't want to be asked anything just now. And don't open your eyes, either. Got it?"

I give a nod as indistinct as her voice.

She removes her finger from my lips, and the same finger now travels to my wrist.

Years later, after moving to New York, I re-engaged my Japanese language studies hardcore. I picked up The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in its original Japanese at Kinokuniya. This was my first attempt at reading novel-length Murakami, and I reveled in it. His prose is delightfully unembellished, and while it will prove difficult to first-time language students accustomed tomanga or Harry Potter in Japanese, I found myself speeding through it. Comparing the original Toru-May passage to the translations, I believe Rubin still captures its mood better than Birnbaum. He nails the girlish, fearless 'tude of May's back-and-forth with this older, slightly naïve guy.

I felt confident that I was reading Murakami as he intended with Rubin's translation. It's a fairly well-known fact that large chunks were excised in the English text (highlighted here in a roundtable email conversation between Murakami translators Rubin and Philip Gabriel, with Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon). Did I miss these sections when I first read it in English? No, but discovering them in Japanese—like an entire chapter's worth—was welcoming. Still, I've spent so much time living in Rubin's translations, navigating well-worn pages, that I return to the comforts of the English-language book without hesitation.

(Part two, on my introduction to 1Q84 in Japanese, to follow)

Photo: Mr. Fee

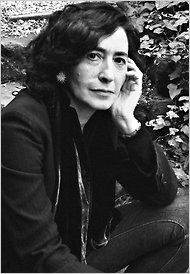

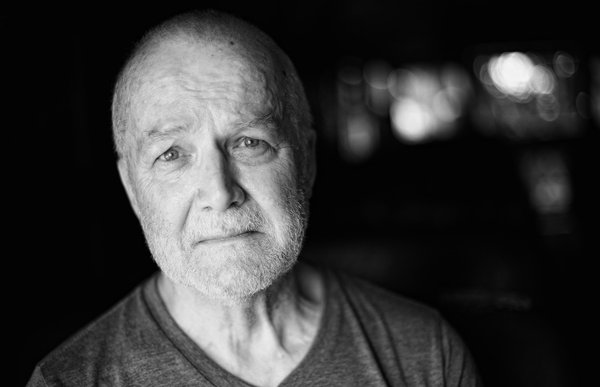

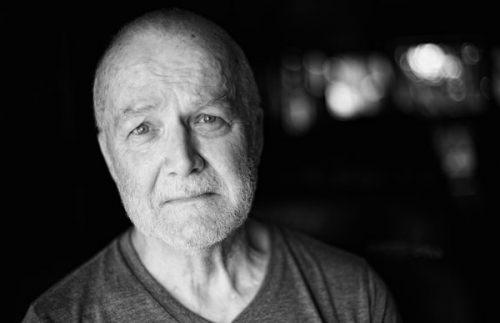

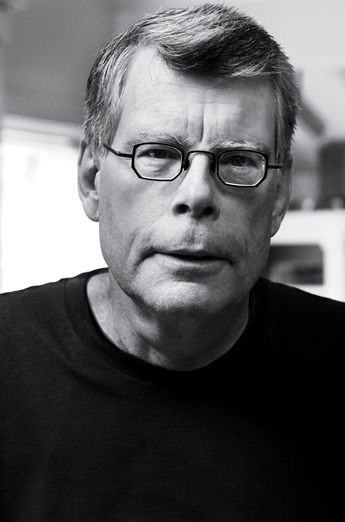

Inspired by the season’s innumerable "best of" lists (and blooming off an earlier post in which I analyzed poets' faces), I decided to take stock of some of my favorite author photos of 2011. For me, great author photos are all about discomfort. The photo shouldn’t convey information about the subject so much as force the viewer to feel uneasy, maybe even squeamish. The goal of the author photo is to make the viewer believe the author has something the viewer must know, that not purchasing and reading the author’s book will have some obscure but detrimental consequence. Here are my top picks for 2011!

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©