While not technically a celebration of pervy exhibitionism, Flash Fiction Day can still be a grand opportunity to expose yourself...to good writing. If you’re in the mood to produce, David Gaffney has some tips up at The Guardian on how to write flash fiction. Though I have to admit, Gaffney sounds more like a short story writer writing in extra-condensed form than a true flash fiction writer. Oh yes: there is a difference.

This is not to say his advice is bad or not useful. Condensing sentences to their essential components is a valiant and essential practice. But I think flash fiction (which I’m defining as any piece of fiction under 1,000 words) doesn’t have to consider plot as an adjustment of traditional notions, such as Gaffney’s advice to “Start in the middle” and to “Make sure the ending isn't at the end.” One of the things I adore about flash fiction is that it can provide the kind of space and attention so that "what happens" is more attuned to the effects on the reader than the characters. If you want to feel that for yourself, check out this barrage of Lydia Davis stories, courtesy ofConjunctions.

For me, flash fiction isn’t just about concision and brevity; it's about allowing for a kind of stillness. It’s there on one page, maybe two. There’s no pressure to rush through it to find out what happens next. Good flash fiction can have such careful, loaded sentences that they can stop you in your tracks. It can allow for a kind of complexity that isn’t about sentences being difficult but about sentences that transform how we think. Economy can give rise to mystery, to tensions underneath and between words.

J. Gabriel Boylen, in a review for Bookforum of George Prochnik’s In Pursuit of Silence notes that “the peak of brain activity, of thinking, comes in the tiny pauses between sounds, when we simultaneously process the previous sound and anticipate the next. When noise never abates, brain activity tends to flatline.” Flash fiction, for me, can allow for this kind of stillness, for a kind of quiet filled with transformative activity.

image: undercheese101.deviantart.com

I have been an admirer of Brian Evenson’s prose ever since I drooled over the stories in his first collection, Altmann’s Tongue—one of the top influences in forming my literary aesthetic, and one of the most crucial collections to come out in the last twenty years. His new collection,Windeye, just out from Coffee House Press, continues the same dark, titillating work I first fell in love with.

In very economical ways, and in a very short space, Evenson creates great rifts of uncertainty for his characters and for the reader. In “Angel of Death,” the narrator, wandering a desolate landscape with a group of eight others, is given the task of writing down the names of those who die along the way. But even this concrete task is complicated—made slippery—by larger forces just underneath the tangible world:

The difficulty comes in knowing what is real and what is not. There is no agreement on this. What I am nearly sure is real are bursts and jolts and the smell of singed hair, but others recall none of these effects, recall other things entirely. And how we came to slip from one dim world and its dim deeds to the place where we are now, none of us are in any position to say. And why we are together, this too I do not know.

What I admire most about Evenson is his ability to arrest me in an extreme state of vulnerability. Whether the narrative is in first- or third-person, it never intrudes to provide concrete orientation. I am as lost, as consumed by disorientation, as the characters. In a cinematic sense, it's as if there is no widescreen shot, no panoramic lens, with which to get a sense of any outside environment. I'm pulled into in this great, unresolved tension that becomes the general atmosphere in which the events of the stories take place. Which is horrifying. And delightfully so.

There is also great physicality in Evenson’s vivid descriptions. His landscapes, while mostly spare, contain specificities of texture that make them come alive. Great attention is paid to the scratches and marks of violence upon bodies. These exquisite details are made all the more terrifying for being the only details to really trust.

If you happen to be in New York, I recommend experiencing Evenson firsthand. He’ll be reading with Dylan Hicks and Ben Lerner at the KGB Bar this Sunday, May 20, and at The Center for Fiction on Monday, May 21. I can assure you: horror might await the characters in these stories, but what's even more delightful is the horror that awaits the reader.

image: coffeehousepress.org

Edvard Munch's existential icon The Scream shattered auction records several nights ago. After months of buildup and a televised diss by New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz, The Scream's 1895 pastel (the sole version of four not owned by a museum) sold at Sotheby's for $120 million. Guests posited whether or not it will be headed to Qatar. Me, I wondered if I'd ever see it in person.

I have complicated feelings toward owning art. I “get” that galleries show sellable commodities, a few of which may enter a museum's permanent collection. Most disappear to private collectors, until they return to the auction block or the unpredictable exhibition loan. And I'm not the type who entertains many invitations to visit these collectors' homes, if you know what I'm saying.

Nor am I immune to art-lust. I discovered, waffled about, and ultimately missed my first chance at ownable art in the two-artist show “Finders Keepers, Losers Weepers” at Jonathan LeVine Gallery. I was infatuated withJonathan Viner's ennui-immersed canvas The Fluidity of Power, and for like two minutes I had a shot at it. Stymied both by the price and the thought of fitting the huge thing in my tiny studio, I capitulated. I'm still kicking myself.

I am reminded of one of literature's most scene-stealing artworks: Hans Holbein the Younger's hauntingly skinny painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. It captivated Fyodor Dostoevsky and is a mortal catalyst in The Idiot, where the plot shifts from rosy-glassed Prince Myshkin laughing with the cute Yepanchin girls to tormented Rogozhin musing about putting a knife in somebody. By positioning a copy of this grotesque masterpiece in Rogozhin's flat, the characters effectively splinter into darker realms. Who knows how it would've gone down if they encountered Holbein in Kunstmuseum Basel, where Dostoevsky saw it in 1867 and where it permanently hangs?

I'm mulling another mood-maker: Fix Me Doll by Tokyo-based artist Trevor Brown. It's a 180 from Holbein but right up my aesthetic alley. I've been a fan of Brown's subversive style for years and wear several tattoos inspired by his work. Fix Me Doll was in Brown's latest show in Ginza, Tokyo's Span Art Gallery, and the clock is ticking before another hardcore fan snags it.

Totally more attainable than The Scream, and perhaps more fun to look at? Ah, I'll probably wuss out.

Images: The Scream courtesy Reuters; Fix Me Doll courtesy Span Art Gallery

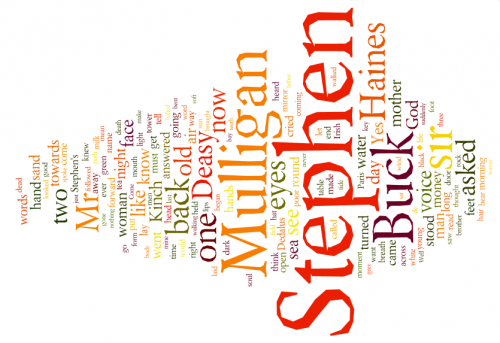

Now that James Joyce's literary corpus is finally in the public doman, I've decided to appropriate it in a singularly 21st-century manner: by readingUlysses chapter by chapter in Wordle, which creates cloud-like infographics based on how often individual words recur in a given text. Visual concordances, more or less.

Each chapter of Ulysses is remarkably different—scholars have noted that chapter breaks serve to shift from one style to another, rather than from one pivotal moment to the next—so I loaded each one into Wordle, let it remove the most common and pedestrian words, and screen-grabbed the results. Here are a few stray observations on the first three chapters, in which Stephen Daedalus's world is fleshed out before Leopold Bloom's arrival.

Chapter 1: Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus (nicknamed Kinch) is talking to his roommate Buck Mulligan in the Martello tower they're both sharing. "God" is mentioned just as often as "mother." The sea and water crop up plenty; the tower is out by the shore, after all. "Mirror" is another popular one, starting with the first line: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." But it's surprisingly renamed in one of Stephen's most famous aphorisms: "It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked looking-glass of a servant."

Chapter 2: Nestor

I've rearranged the words here to keep "Stephen" separate from everything else, since this chapter focuses on Stephen's job teaching, as well as his uncomfortable relationship with the elder Mr. Deasy. There is a great deal of authority and deference in the classroom and in the office: "yes," "sir," and the verbal conjugations of asking and knowing and crying and answering. The word "history" is hidden but memorable here, just as important as books and, ironically, even more recurrent than God: "For them too history was a tale like any other too often heard"; "All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God"; (best of all) "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Chapter 3: Proteus

Stephen's name is all but swallowed up in this chapter, which ditches its protagonist for the "ineluctable modality of the visible." Instead of names, there are his eyes and the sand, everything to see beneath his feet and behind his back. Of all the German words, "nebeneinander" (n:coexistence; adj: in parallel) is the only one frequent enough to appear here. "God" is again recurrent, but not nearly as much as "Paris" or "woman." Everything here boils down to immediate perception and thought, from the concrete elements of the sea and the shore to the clearly abstract mental verbalizations of that which is ineluctable.

I've already read Ulysses once, in an eight-day marathon as a bet with my friends, and while I enjoyed the shifts in perspective the first time around, I wouldn't have thought that the words would mark it out so clearly. I also hadn't thought about Ulysses in religious terms, so seeing the relative prominence of the word "God" in each chapter tells a story I hadn't noticed before.

Cool stuff. If nothing else, with word-clusters like "God Like Mother," "Look Back Sargent," "Eyes Going Kiss," this thing's a band-name factory.

Flavorpill’s list of cryptic book titles—including the just released HHhH, which got my bloggin' buddy James all infranovelistic, and last year’s C—brought to mind the Diagram Prize, which is awarded yearly to books with the strangest titles. Sometimes the quirk isn’t just contorted syntax or the result of concision; sometimes it's more about semantic friction, when a literal meaning scrapes up against your capacity to make sense. Like last year’s Diagram winner: Cooking with Poo. (Just in case you wondered, Poo ain’t shit.)

Presumably the publisher hoped to cash in on our confusion. After all, titles have to pop. And publishers serve two masters: commerce andcreativity, profit and art. Titles have to be memorable enough to stick with readers, yet clever enough to intrigue tastemakers. No easy task. Try too hard and you end up with something like House of Leaves. Do you get it? The house is really the book, cuz pages can be called leaves! Oh man, so clever! That one, at least to my ears, is a little too proud of its punning. Yet here I am, discussing it.

Others titles have impressed me more. Here's a list of some of my favorites, and what I think makes them work.

- The Crying of Lot 49. Thomas Pynchon’s slightly paranoid novella has stuck in my brain since I first glimpsed its title. It must be that howling gerund with its long i sound and suggestions of pain. And then there’s the title’s sonorous quality. It begs to be spoken aloud. Try it a couple times. Really.

- Euonia. Okay, basically this title banks on obscurity. You probably hadn’t heard the word “euonia” before you heard about this book. It means “beautiful thinking.” It’s also the shortest word in English that contains all the vowels, which makes it a particularly fitting title for Christian Bök’s exercise in constrained writing. Each of the book’s five chapters uses only one vowel, beginning with a, ending with u. The book is a striking thing to read, especially the guttural u chapter.

- Life A User’s Manual. The intricate phenomenological descriptions that George Perec composed for this book—each chapter describing a single room in the apartment building where the protagonist, a recently deceased guy who liked jigsaw puzzles, lived—aren’t exactly what you’d expect to find in a typical user’s manual, but this is life, not a screwdriver. The title sticks with you because most novelists (not to mention most publishers) don’t have the nerve to put a technical sounding title on their novels; such a thing might dissuade impulse buyers.

- Watership Down. Amazing use of ambiguity here: you don’t really think of Watership Down, the hill, when you first read it. Instead, you picture a curious seafaring vessel, "down" as in sunk or in the process of going down. Then you read about rabbits and "hrair limits" and it all begins to make a bit more sense. But at that point, you’ve already been led down the garden path, and the title is ensconced in your memory.

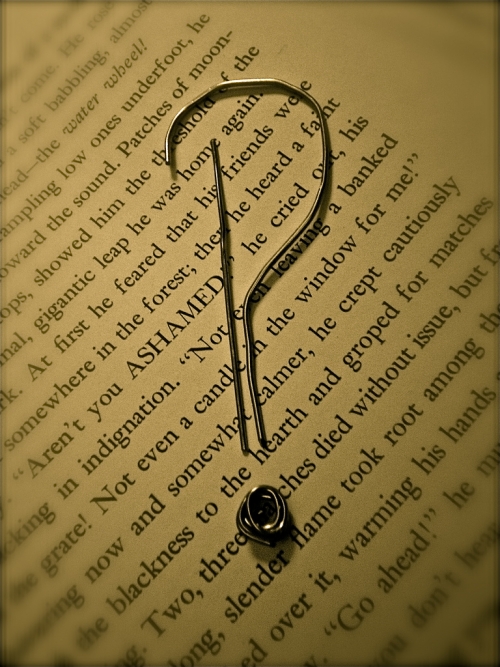

Those titles are solid enough to serve both art and commerce, I think. Of course, I doubt they’re as brilliant as my idea for a novel concerning self-motivating punctuation marks. The title's not gonna be written out but set with the interrobang glyph. I'll let the critics argue about how to pronounce it. And yeah, the gimmick is that the narrator's deployment of punctuation marks evolves as her narrative unwinds. it'll be nigh unreadable, but oh so punny and witty. Beat that, internets.

Image: flickr user GardenofEdits

HHhH, Laurent Binet's account of the assassination of a top-ranking Nazi in 1942, is divided into 257 mini-chapters. In an attempt to comprehend Binet's layering of fact and fiction, as well as the totally incomprehensible era he describes, I'm going to try out his "infranovel" techniques myself.

Read More

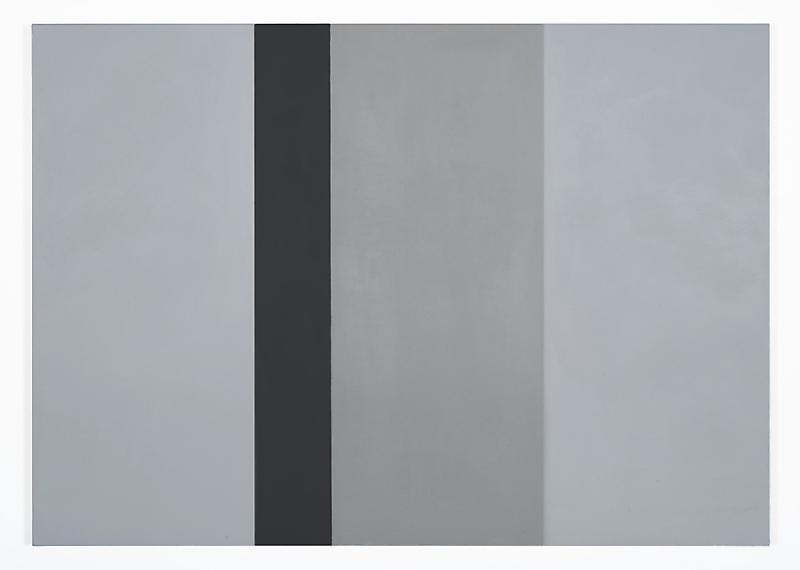

I find The Paris Review's literary paint chips feature—“paint samples, suitable for the home, sourced from colors in literature”—totally sublime. Their 28 choices, including the requisite Fitzgerald (“Dock Green") and Hemingway (“Elephant Hills”), suggest Gerhard Richter's color-chart paintings: systematic permutations of chromatic variety, as mundane as industrial paint samples yet as thrilling as exploring every possibility of hue and tone.

Okay fine, I'm also an art nerd. So the literary paint chips got me thinking: what happens when you locate these colors in real abstract art?

Think of the possibilities not covered here! Those high-altitude sunsets in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain, or Füsun's tear-reddened eyes in Orhan Pamuk's The Museum of Innocence. The “dead channel” sky of William Gibson's cyberpunk classic Neuromancer could be a flickery gray-green...if, thanks to Gibson's now-retro vocabulary, we can remember what “screen snow” even looks like.

Images: Gerhard Richter courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art; Brice Marden courtesy Wikipedia; Agnes Martin courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York; Mark Rothko courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Byron Kim courtesy James Cohan Gallery

Since passing in 2003, Roberto Bolaño has published a lot of books, probably more than you or I will put out in our combined afterlives. Because once you get famous—and you must be pretty famous if Heidi Julavits and other lit bigwigs are singing your praises at Galapagos—it’s not just your finished work that attracts readerly eyes. Some greedy fans will find the time to scrutinize marginal notes in your correspondence or drafts and sketches taken from your computer. When it comes to Bolaño, I am one of those eager gleaners; I have been ever since The Savage Detectives made me regret my somewhat sensible (read: mostly boring) life and pine for those of its voluntarily down-and-out (read: awesomely authentic) characters.

So I was excited about The Secret of Evil, the latest of Bolaño’s work to be translated into English. It’s a collection of “stories,” though it contains some of the putatively autobiographical work released last year in Between Parentheses (including a favorite of mine, “Beach,” the account of a recovering dope addict—perhaps Bolaño, perhaps not). That The Secret of Evil draws from the previous book is suggested even in its design: Evil has a blind embossed set of horns on its dust jacket, recalling, in invisible tactility, the foil-stamped parentheses on the cover of the former collection. Clever clever.

I’ve invested a lot of time both in Bolaño and Arturo Belano, the former's fictionalized self. But what about you non-fanatics? What would you think of the The Secret of Evil? It’s a solid collection of stories, sure, but some of them are hard to appreciate without the rest of Bolaño’s writings there in the background. And unlike, say, 2666, this was in no way close to being finalized for print.

Evil also marks a turning point in the way we pilfer dead authors’ “papers.” Its introduction goes into some detail about how the pieces were taken from Bolaño’s computer, going so far as to name the files it drew from. Hard-copy drafts are probably a thing of the past. The next thing to disappear may be the locally stored digital file; instead, all our manuscripts will be up in the cloud. And, of course, letters: they’re dead, and we're sure to see more and more volumes of email correspondence.

What's next? Maybe writerly Twitter and Facebook accounts will be combined with smartphone GPS logs—along with, we gotta hope, those of the writer's spouse, friends, publishers, fuckbuddies, etc.—and published as an app. Then future academics will make observations like this: "It appears that Rushdie was more prolific in the days he spent with Lakshmi than when he was when he was about town with Lieskovsky. I will use this dataset to to construct an algorithm that rates muses like Klout does social media yuppies."

The digitization of everything is gonna make for exciting, horrifying stuff, people. Just hope you don't become famous. Because if you do, you will have no secrets, no secrets at all.

Image: flickr user Kleiber Fragoso

If you, like me, grew up in the '90s, you're probably familiar with the dilemma of blocking out parts of that decade whilst embracing others. For every instance of President Clinton ripping into a sax solo on The Arsenio Hall Show, there is smooth-jazz circular breather Kenny G butchering the damn instrument. Another case in point: the Awl's profile on Dustin Mikulski, known to the world as the Dancing Baby from Ally McBeal. The fact that this man, once a cha-cha-ing child whose birth coincided with that of viral video, can still draw a crowd, proves our enduring love/hate relationship with that schizophrenic decade.

Whatever. Dancing Baby can oogachaka his animated ass outta here. It's one facet of the '90s I wish would disappear, like JNCOs and Beanie Babies. Now '90s music...that's a complicated one, encompassing both Kurt Cobain's suicide and 2Pac's murder. Then again, with 'Pac's hologram sharing the stage with Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre at Coachella, the '90s have never felt so close. Below are a few songs that, to me, define the decade and its transitions between Kurt and that demonic dancing baby—but I'll be damned if I include Aqua.

1994: Nirvana, “Drain You” (live on French TV). Recorded just two months prior to Cobain's suicide, and his chill-eliciting scream still hits me hard. I was just a kid but Nirvana meant the world.

Late 1994: The Prodigy, “Voodoo People.” Charred breakbeats collide with a sampled punk guitar riff. If America could only predict dance music's ubiquity in the following years: just look at the damn commercials, like Mr. Oizo's "Flat Beat" advertising Levi's or that Mitsubishi honey popping to Dirty Vegas' "Days Go By."

Late 1994: Lush, “Hypocrite.” I fell I love with a girl, and she was the Kool-Aid-coiffed frontwoman for Lush, Miki Berenyi. They and (London) Suede were sharp answers to the Britpop.

1995: Massive Attack, “Karmacoma.” The Bristol sound: suffocating sonics and sinister soul. Plus, Tricky (who released his superlative debutMaxinquaye that same year) shares the mic.

Late 1995: 2Pac, “California Love” (feat. Dr. Dre). Pac's comeback track was a sunny exhale of West Coast love, but it was shadowed by his untimely death less than a year later.

1996: Smashing Pumpkins, “1979.” Emo wasn't a widespread term in Texas back in '96, but this guitar-glistening anthem provided the emotional background music to my formative days.

1997: Roni Size/Reprazent, “Brown Paper Bag.” So technically this live clip is not from '97, but this Bristol-based drum-n-bass ensemble won the 1997Mercury Music Prize for their jazz-inflected tracks (beating out Radiohead'sOK Computer and Spice Girls' Spice, just to keep the whole thing in perspective). All you dubstep heads: this is how you bring the bass.

1998: Usher, “Nice & Slow.” Check it: 1998 is the year Dancing Baby debuted on Ally McBeal. It's also the year R&B phenom Usher dropped this breathy single. Just think what this track meant for a sensitive young high-schooler with a learner's permit. As Usher croons: "now here we are, drivin' 'round town. Contemplating where I'm gonna lay you down." Poetry, man. Grunge felt a decade away.

Long live the '90s, I say!

Image: Memesgroupproject (Dancing Baby) and Wikipedia (Tupac Shakur), slightly photo-chopped by the author

Whenever I hear about The Great Gatsby, my mind shuttles to a passage of Haruki Murakami's Norwegian Wood, one of my oft-read favorite novels. Like me, the protagonist Toru is a serious rereader: “This is my third time through [Gatsby], and every time I find something new that I like even more than the last time.” So it's not too surprising that The Millions (and a linkedGuardian article) posits The Great Gatsby as the most “rereadable” fiction. Since my rereading habits tend to change with the seasons, let me offer a few recommendations for winter nesting, summer tanning, astral projecting, and more.

• Cocooning for the winter: I plowed through Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Idiot and Crime and Punishment in a chair next my studio's radiator, where the hiss and clatter of pipes covered whatever music was playing the background. To me, they're the most cold-weather appropriate of this Russian's enveloping oeuvre.

• Beach jaunts: Thomas Mann's Death in Venice radiates with dry summer heat and soothing Adriatic air, and its novella length is perfect for beach reading (tack on 45 minutes for the Nassau County train ride). Dostoevsky's short novel The Gambler is another warm-weather favorite—and I'm admittedly smitten with Mlle Blanche de Cominges.

• Emotional inspiration, in brief: Anton Chekhov's short stories never fail me. “The Huntsman,” “Anyuta,” and “The Black Monk” are major tearjerkers—and with Chekhov's unbelievable gift for brevity, “The Huntsman” achieves this over barely four pages. I share these with girls to show them that I am a sensitive dude.

• Emotional inspiration, long read: Zadie Smith's The Autograph Man...and yes, I love White Teeth as well. I met Smith at a reading back when The Autograph Man debuted (she read the prologue, another significant tearjerker), and I've returned to her idiosyncratic second novel ever since.

• Far East escapism: Haruki Murakami's pop psychedelic The Windup Bird Chronicle. I've written about this before for Black Balloon, and it's my go-to for getting “away." Plus, Dance, Dance, Dance is one heady trip (psychic teenagers and talking sheep, anyone?).

• Even farther (like another universe) escapism: Douglas Adams' The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, or as the subheading reads: “five novels in one outrageous volume.” I tend to tucker out at So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, but it's still a stellar ticket outta here. Towel not included.

For my fellow rereaders, I close with a helpful tip. See, my Manhattan studio couldn't accommodate a proper library, but my reading habits demanded one. To combat my finite space, I read and re-read certain novels until I'd exhausted them, and then I shipped them back to my parents so I could buy more.

But the Murakamis, the Russians, Zadie...those I made room for. Who needs a bathtub, anyway?

Image courtesy the author

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©