Hotels that emphasize shagging over slumber get a bad rap in the States. Think about it: a dusty gyrating bed, a coin-operated TV chained to the floor, broadcasting 217 flickery channels of porn—plus Animal Planet for the truly deviant. Photographer Misty Keasler (interviewed here in the Morning News) offers a radically different perspective in her series Love Hotels: The Hidden Fantasy Rooms of Japan and the same-named monograph, exposing the West to sanctuaries equal parts shockingly subversive and substantially sexy. In sum: Hello Kitty S&M Room.

As a frequent traveler to Tokyo—and connoisseur of its nightlife—you better believe I know a thing or three about love hotels. Before I file a “Raw Nippon” post on where to get your jollies (or just where to bathe in a couple-sized martini glass), I gotta clarify something. The following list, a cross-section of pop culture, shows that love hotels are more than just destinations for debaucherous denizens (though there's plenty of that).

William Gibson, Idoru

The cyberpunk scribe's 1996 novel, weighing a crystalline Far East against a murky, sodden London, was my gateway to love hotels. Their dual nature—intimacy and isolation—is spelled out in an exchange between young protagonist Chia and her geekish ally Masahiko:

“Private rooms. For sex. Pay by the hour.”

“Oh,” Chia said, as though that explained everything... “Have you been to one of these before?” she asked, and felt herself blush. She hadn't meant it that way.

“No,” he said... “But people who come here sometimes wish to port. There is a reposting service that makes it very hard to trace. Also for phoning, very secure.”

Haruki Murakami, after dark

This taut little 2004 read occurs totally at night, featuring a love hotel as a major plot element: the scene of a violent crime and a retreat for protagonist Mari. As Hotel Alphaville owner Kaoru explains to her, “it's a little sad to spend a night alone in a love ho, but it's great for sleeping. Beds are one thing we've got plenty of.” Nightly rates at love hotels are typically less than those of business hotels, if you're shrewd.

Laurel Nakadate, Love Hotel and Other Stories

Nakadate's career survey Only the Lonely at MoMA PS1 last year included her 2005 single-channel video Love Hotel, featuring the artist slow-grinding on gaudy beds throughout Japan. Though we can imagine the camera as the observer's seeking gaze, simultaneously it is solely Nakadate, awaiting a partner never to appear. “It's about loneliness,” she explained. “About being by yourself in a place where you're supposed to be in love.”

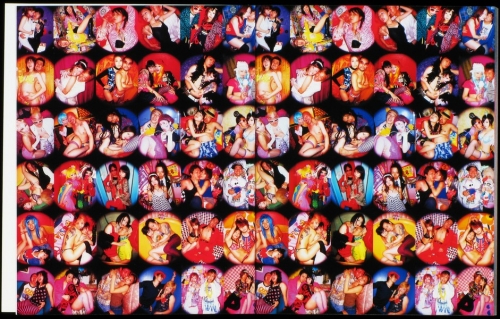

Nobuyoshi Araki and Nan Goldin, Tokyo Love and Photographer HAL,Pinky & Killer DX

Two glossy photography books, the former from '94 and the latter over a decade later, celebrate love hotel patrons as much as the kaleidoscopic environs themselves. In Tokyo Love, Araki, the mad lensman of Japanese eroticism (see Tokyo Lucky Hole) and post-punk documentarian Goldin teamed up to capture indiscriminately youths in love. For HAL (his nom de photo), a mainstay of Golden Gai, Pinky & Killer DX was a close-cropped and super-saturated exposé on Tokyo's lusty after-hours lot. Funny thing is, each time I visit Tokyo I meet several more subjects from HAL's lens.

Images: Photographer HAL Pinky & Killer DX via Photoeye.com; Idoru/after dark collage via Project Cyberpunk and Bull Men's Fiction; Laurel Nakadate via Danziger Projects

Apparently, Colm Toibin's book New Ways to Kill Your Mother, published by Scribner this month, doesn’t provide any instruction on how to actually kill your mother. While this might be a grave disappointment to some, I’m inclined to smirk (with both glee and a bit of friendly mockery) at Toibin’s recommendation to put mom on ice—at least in fiction. Dwight Garner, reviewing the book for the NYTimes, explains: “His essential point, driven home in an essay about all the motherless heroes and heroines in the novels of Henry James and Jane Austen, is that ‘mothers get in the way of fiction; they take up the space that is better filled by indecision, by hope, by the slow growth of a personality.’”

Really, aren’t fiction mothers just a pain in the ass? If a novel has a mother in it, she’s usually too complicated and infuriating to develop in a half-assed way, and so the whole book ends up being about her. She’d just love that, wouldn’t she?

If you're a writer, you’re stuck having to acrobat around a reader’s wondering, “Where is the character’s mother? Does she know what her son’s doing?” every time you want a character to do something bad. Raskolnikov was gonna kill that landlady but then his mom came home. Groan. Guess he’ll never be friends with that prostitute.

Toibin points out that orphans are great characters in fiction, and really, how could they not be? Without all of that guidance, nourishment and guilt-mongering, orphans are free to find their own way in a world devoid of preconceived notions. Plus, devastation and an incurable longing are great ways to secure a far-reaching and easy sympathy from readers. Oh, the poor dear, that’s why this character’s acting up.

Still, I find this proposition of parentless fiction a little weird. Possibly indicative of a handful of bizarre psychological ramifications. Do we have a hard time imagining mothers without pillows clutched in their fists, coming to snuff us out? Do we really think that kids raised in two-parent households are so adjusted as to be boring? Are your parents making it hard for you to develop a personality or experience indecision and hope?

I love a little mom in my fiction. I say the more mothers, the better.

image: bbc.uk.co

Boozing is an awesome anytime activity in Tokyo. 7-Eleven tallboys and your average bar's draft run hundreds of yen cheaper than a cappuccino, and since trains stop running at midnight, nearly all watering holes remain open and packed until dawn. But to cultivate that Cheers-like vibe, in a joint a tenth of the size but with 10,000 times the character...that takes some effort. I spend my time in Golden Gai, a network of narrow alleys whose collective footprint approximates Tompkins Square Park, yet is filled with some 200 unique, tiny-ass bars.

Where to go? The shockingly pink Love and Peace? The jazz-eclectic Dan-SING-Cinema, up a crippling flight of stairs? (Most of these bars stacked two high.) The geek-chic Bar Plastic Model? Be warned: there will be “seat charges,” either a flat fee or hourly rate to sit your ass down and drink. That's because all these joints have regulars—artists, musicians, writers, whatever—who expect their usual seat (of like eight). Bar-hopping in Golden Gai gets expensive quick.

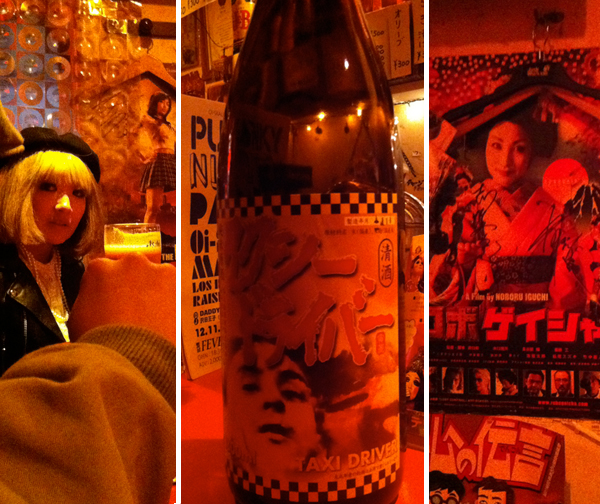

Luckily, I found my Cheers. It's called Darling.

Japanese splatter film posters (Robogeisha and The Machine Girl anyone?)—most of which feature acting by Darling's charming owner Yūya Ishikawa—blanket the cramped space. If Yūya's in the house, then Group Sounds-era crooner Kenji Sawada will be wafting from the stereo. Otherwise, expect jazz or Motörhead, as cutie bartender Ichiko serves a full spread of the harder stuff. To offset that 800-yen seat charge (and dull the booze), Ichiko adds a complimentary snack. One night I swear it was a mini chalupa, likeOrtega-style—I don't know how she made that in Darling's dollhouse-sized kitchen.

The J-Horror world frequents Darling, plus Eiga Hiho journalists like Yoshiki Takahashi (those extra-splattery posters and “Taxi Driver” sake label? All Yoshiki-designed) and noise musicians. If I'm lucky, Tokyo Dolores pole-dance troupe leader Cay Izumi. If I'm luckier, a handful of Mutant Girls Squad actresses.

Last December was Darling's sixth anniversary, coinciding with Yūya-san's birthday and the evidently rare Japanese lunar eclipse. A crowded night of “飲み放題” (“all-you-can-drink”, truly an awesome concept) and debauchery ensued. I'd been frequenting Darling for over a year then, and I never felt closer to home.

If you end up within Golden Gai, I suggest Nagi—a Fist of the North Star-themed ramen joint—as your pre- or post-drinking nosh spot. Nagi's unctuous, garlicky deliciousness is guaranteed to soak up any alcoholic embers. Plus, any woman willing to get near my post-Nagi breath is A-OK in my book.

Images: overhead shot UnmissableTOKYO.com, all Darling photos courtesy the author

On my recent trip to Tokyo, I saw three indie bands with slightly funny-sounding names over three consecutive nights. J-Pop megagroups likeAKB48 (and their “warring” sister factions SKE48 and badass Kansai-basedNMB48) may blanket airwaves and adverts, but the indie scene is a-boomin'. I learn something new each time I attend a Tokyo indie-rock show. Considering these three were back-to-back, I learned a lot. Here's some of that!

* Who the Bitch: everyone gets to mosh, if you want to! Two riot-grrrls and a dude resembling an extra from Nagasaki jet-rockers Guitar Wolf playing punchy pop-punk. The crowd had been circle-pitting nonstop when the band launched into riff-heavy 「ベクトル」 (uh: “Vector”?), guitarist Ehi crooning “come back to me in my bed” (in English!). Want some of the action? The big crowd-control dude moshing along will see to it you get your moment of stage-diving fame. Don't want to? Cross your arms NYC-style, and even the wildest kids will politely avoid crashing into you.

* 住所不定無職: ease back on taking photos and just have fun! These vintage clothing-coordinated indie-pop girls met at the unemployment office, hence the translation of their name: “no job nor fixed address”. I was up front and right-of-center to photograph cutie Yoko, co-vocalist and player of a glittering double-neck bass/guitar—but I held off. I alluded in my previous Tokyo indie-rock post that photography is generally verboten. How refreshing to just experience their upbeat, singalong anthems without studying an iPhone screen!

(speaking of Guitar Wolf: they headlined this show, and I've never seen so many white people at a Tokyo indie show before. Guess how many were taking photos!)

* Plastic Girl in Closet: Japanese shoegaze rules! J-Pop may rule, but the Japanese do some mighty fine—and ferociously loud—shoegaze. The adorable four-piece Plastic Girl in Closet celebrated their third LP ekubo(“dimple”, a nod to their twee-ness) with their first-ever “one-man show”, ripping through their back catalogue for nearly two hours of sonic bliss. That the long-delayed My Bloody Valentine reissues coincided with this show felt particularly auspicious. For beyond the guitar squalls and ethereal vox, it was Ayako's muscular basslines that really shined, up there with MBV's Debbie Googe.

* reserving tickets: perhaps it's thanks to these bands' indie-ness, but each offers to reserve advance tickets, so long as you email them. You still have to pay, but at least you've secured a spot in one of Tokyo's “cozy” 100-person capacity live-houses.

Image collage: (clockwise from top) courtesy 住所不定無職, Plastic Girl in Closet, Who the Bitch

Bookstores seem to be thriving in Tokyo. I can't walk two blocks in any direction without seeing the cheery character for book, “本”. Those searching for the rare vintage edition or secondhand paperback get their fix in Jimbochō. This neighborhood lines one broad avenue (plus myriad side streets and back alleys) with tons of used-book shops. And as this is Japan, it's all about specialization, with paperback “general stores” outnumbered by closet-sized nooks crammed with French classics, music magazines, and hairspray-heavy '80s porn.

Kanda Kosho Center (named both for the Chiyoda Ward district and for the literal translation of used books, kosho) is Jimbochō's used-book gateway, nine floors of categorized havens kitty-corner from the train station. The handy placard posted adjacent to Kanda Kosho's lifts is of no use if you don't read Japanese, but no worries: poke your head into a shop, and even the skeeziest porn joint's owner won't give you a passing glance.

Want a three-volume set of The Fishes of the Japanese Archipelago, back-issues of Japanese-language rugby magazines (who knew??), or a monthly periodical pointedly titled Gun? Those can be had on the third and fourth floors, respectively. Miwa, the all-kids bookstore on 5, features Golden Books from an alternative universe, like “Oden-kun”, whose titular hero is an anamorphic daikon radish. Beyond the wonderful jazz and classical record shop crowning Kanda Kosho, the upper floors all house unrelated porn shops, their otherwise muted environs punctuated by the sharp crackle of individually-sealed plastic wrappers, as customers dutifully pull out and shove back periodicals like Cream and Scholar from overstuffed shelves.

Let's say you didn't find that specific skin-mag you so desired. You're totally in luck! A brief jaunt off Jimbochō's mainstream is Aratama Total Visual Shop (the “visual”, written in English, is a clue they sell lots of nude stuff) and its mirror-façaded, younger kindred. The latter is stocked almost entirely with bondage and fetish magazines, which surprised even this intrepid reporter in their diversity. Aratama the elder contains an encyclopedic array of AV photo-books and PG-13 gravure mags, but its achievement is a whole room of posters and life-sized cardboard cutouts of cuties. The addition of sealed, autographed photographs of various models (going for like $150-400 per 4x6” print) feels almost superfluous.

I can spend hours in Shinjuku East's Kinokuniya, the ferroconcrete bookstore behemoth that makes its shiny Manhattan cousin feel absolutely puny by comparison. But for those treasured and unique—yes, sometimes very deviant—finds, Jimbochō is the only destination.

Images: courtesy the author

Translators can be any number of things: imaginative remakers, clever conduits. They are invariably people who try to share the sense of the original but do so wrongly, in goodbad faith. Such is Antigonick, Anne Carson's new translation of Sophokles's Antigone, a version for people who don't read Greek, don’t veil themselves in the manner of the ladies of antiquity, are not eligible members of the nonsensible chorus, but have read Hegel’s remarks on unmatched justices and (snotty children) assume some things about matching them right.

Antigone, the character, is a hard target. She’s moved so much that she no longer moves at all, undead but buried and constantly dug up again, a fixture of antiquated academic culture obsessed with dust. There are paintings in Antigonick on nice vellum pages that overlay the text—which seem to be handdrawn by Carson herself. Bianca Stone drew them in fact, while Robert Currie made text and image look nice together.

What information from the Greek source text is relevant? How can we relate to Antigone, who chanted a strange language and opposed her city's laws?

The problem of translation is the problem of meaning is the problem of wanting to share some sense in a world where, oh sweet gnarly luck, sharing said sense is like kissing a salt lick. Understandably, translators translate in distinct ways, but always to differing levels of failure. They can be faithful, trying hard to render, fideliciously, the flesh of the text body they're working. Or they can do as Carson does for Antigone: Paraphrase Beckett. Tell Kreon to fuck himself. Do what’s right. Then, die.

I’m sorry, there was something about justice?

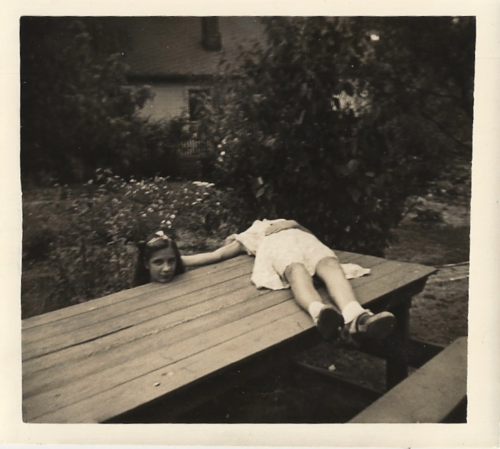

Image: Black and WTF

The Millions' Bill Morris may wax poetic on one-word book titles, but I don't love 'em. Irvine Welsh triumphed with his drug-fueled, dialectically impenetrable debut Trainspotting. But then the one-worders kept coming, like a never-ending belch, from Filth and Glue to Crime and the spanking new Skagboys (available to us Yanks in mid-September).

Why? Morris notes “at their best, one-word titles distil content to its purest essence, which is what all titles strive to do, and then they stick in the mind.” This suits Nobel Prize-winner Orhan Pamuk's Snow, whose austere title foregrounds its melange of political discussions and cultural tensions in a northeast Turkish town. By Morris' reckoning, Snow might be filed under “Place Names That Drip With Atmosphere” or “One Little Word That Sums Up Big Consequences” (a blizzard shuts down the city, sparking dialogues between the narrator and various revolutionaries that nudge the plot to full throttle).

A quick scan of my bookshelves yields another category: made-up words. Jam several novel-related concepts into one tasty idiom, linguistics be damned. Cyberpunk is notorious for this, though I give props to William Gibson's Neuromancer. It's a perfect amalgam for protagonist Case's virtual-reality hackings and...well, the book is totally romantic. Not just razorgirl Molly Millions, but the grimy, metallic, neon future itself. Tokyo on steroids.

Franz Kafka's Amerika deftly encapsulates a young European emigrant's warped stateside wanderings by distorting the title's spelling. This was actually literary executor Max Brod's doing: the working title was Der Verschollene (The Man Who Disappeared). Kafka's other novels, The Trialand The Castle, require their definite articles: the former personalizes Josef K's prosecution and subsequent tribulations—his “trial”—while the latter makes that inaccessible fortress physical to the alienated land surveyor.

This grave importance of “the” and “and” prevents further whittlings down of other titles. I might shorten Fyodor Dostoevsky's final classic The Brothers Karamazov to simply Karamazov, considering the notoriety of that name. As Makarov explains early on: “The whole question of you Karamazovs comes down to this: you're sensualists, money-grubbers, and holy fools!” But Crime and Punishment requires that “and”, balancing cause and effect. LikewiseThe Idiot, as excising that “the” might cast it the way of habitual singularizer Chuck Palahniuk (see: Choke, Rant, Pygmy et al.).

Fine. One-word titles can work, but something must be said for wordy ones. Isn't there charm within Douglas Adams' Britishly prolix The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and—my personal favorite—The Restaurant at the End of the Universe? Even the briefest, Mostly Harmless, requires both words for the Guide's cheeky description of Earth. In this sense, Adams' debut “could” be truncated to The Guide, but that pesky “the” is mandatory. It's not justany guide, after all.

Image: courtesy the author

Virgina Woolf lives on in strange ways. She and Leonard Woolf startedHogarth Press in 1917 to publish themselves as well as their colleagues in the Bloomsbury group. Woolf published some of her most radical and explicitly feminist titles, including Mrs. Dalloway, under this aegis. By the 1940s, however, the press was defunct. And now, Lazarus-like, Hogarth has returned, thanks to Chatto & Windus in the UK and Random House in the US. So will this new incarnation, with such a loaded name and history, be able to shine a light on contemporary gender issues the way Virginia Woolf did almost a century ago?

I decided to read the first two books published by the new Hogarth to find out. And, as a male reader, I was surprised by the different ways Anouk Markovits’s I Am Forbidden and Stephanie Reents’s The Kissing List illuminated the experience of being female in our time.

I Am Forbidden is the story of two sisters within one of the most deeply Orthodox sects of Hasidic Judaism, Satmar. In this world, religion dictates which books they may read, which men are qualified to marry them, when they are permitted to have intercourse. As one sister decides to leave the fold, I waited for the author to take sides. But Markovits does not choose; she simply tells the story of both sisters, focusing on the complications and strains of each path. How can a barren Satmar woman ever hope to bear children if her husband is not permitted to spill seed outside her body, even for the medical tests that could determine the cause of their infertility? Somehow, Markovits is able to show how each character’s outlook prevents her from accepting the facile solutions I might have offered as an uninformed outsider. If fiction is about helping us understand other people, Markovits has succeeded brilliantly.

The Kissing List, on the other hand, is wholly urbane, following a group of four girls through years and cities in a set of linked stories. Like a Sex and the City for twentysomethings fresh out of college, the stories circle around failed relationships, imperfect jobs, and the enduring value of friendship. In each story Reents adopts a different style, from straight first-person narration to email memos and multiple-choice questions. Virginia Woolf would have applauded both their sexual freedom and Reents's stylistic liberties, but I finished the book confused by how these women couldn’t solve their own problems. They were self-made, yes, but they hadn’t found a stance to champion. "Is this what it’s like to be a female today?" I asked a few of my girl friends. I hoped my befuddlement wasn't just due to differences in plumbing. Sadly, they all nodded.

In A Room of One's Own, Woolf discusses androgyny in the mind of the author: “it transmits emotion without impediment...it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.” I may have seen that incandescence more clearly in I Am Forbidden than in The Kissing List, but the fact that these books breathe new life into these questions makes me optimistic for the future of Hogarth Press.

image credits, L to R: modernlitclub.blogspot.com; goodreads.com; goodreads.com

A recent Brain Pickings post on Gertrude Stein’s posthumously published children’s book, To Do: A Book of Alphabets and Birthdays, has sent me on a journey to nonsense. Or rather, it has revived a kind of determination to spread an enthusiasm for reading with your guts and heart, not just your head.

In a press release for her first children’s book, Stein wrote something that could just as easily be applied to her grownup fiction:

Don’t bother about the commas which aren’t there, read the words.

Don’t worry about the sense that is there, read the words faster. If you

have any trouble, read faster and faster until you don’t.

While it’s easier to calibrate your expectations of deliberately nonsensical writing, e.g. Lewis Carroll or Edward Lear, reading for purposes other than understanding gets tricky in other areas. At least, in my mind, readers often resist writing that doesn't immediately make sense, that proceeds with a certain tension-filled ambiguity.

Last week, I came across an htmlgiant post that might be useful in terms of articulating a purpose for reading other than understanding. Before recommending five works of theory (touching upon such topics as "interassemblage haecceities"), Christopher Higgs writes:

I think it’s quite productive to read theory as if it were poetry or fiction,

which is to say as if its primary function was to affect rather than educate...

I read theory and fiction and poetry to experience, to consider, to become

other, to shift, to mutate, to change. I most certainly do not read those things

to understand them.

I was reminded of the first time I encountered Foucault, Derrida, and Lacan in an undergraduate literary theory course (which yes, meant that I was reading in order to understand what was being written). Part of my absolute joy at reading theory was the complete tizzy my head went through in its attempts to grasp or even contain the expanse of the ideas written down. The joy, for me, was the experience of reading it. At times I barely thought my feet were touching ground. In the end, I believe I understood less. And this is wonderful.

My point is not to bash understanding or encourage everyone to smoke pot and listen to whale sounds. I mean, go ahead and all, but what I’d like to promote here is an experience of reading that doesn’t insist on pinning something down. Do not be afraid. Try not to read with the goal of saying “Aha! I get it!” when you’re finished. Allow for uncertainty, for ambiguity, for mystery that resonates beyond the page. Let your senses experience a truth your mind can't get a handle on.

This is also not to encourage laziness; quite the contrary. This is to encourage a kind of pleasure in the sound of words and the power of words to bring you to an unrecognized place.

Don't bother about the commas.

image: guardian.co.uk

Launched twelve years ago, the Caine Prize celebrates short fiction from Africa. And judging by 2002 Caine winner Binyavanga Wainaina's scathing satirical article "How to Write About Africa," it's about time. In collaboration with The New Inquiry and a horde of like-minded bloggers, I’ve been writing about this year's five finalists—and linking to each story so you can read it yourself.

Part 5: South Africa's Riddles

As I read Constance Myburgh’s “Hunter Emmanuel,” [PDF] I was reminded of the literary critic Michael Dirda’s recent Q&A on Reddit:

More than 30 years ago I predicted that mainstream literature would be invaded by "genre" fiction, and this seems to be happening. Writers like Jonathan Lethem, Michael Chabon and others came out of science fiction and comics...I think that we are seeing what SF critic Gary Wolfe calls the "evaporation" of genre lines, and fiction is bursting with all sorts of new inventions and possibilities.

“Hunter Emmanuel” is a hard-boiled detective story torn straight from the headlines of the nineteen-forties. It was published in Jungle Jim, which bills itself as an African pulp fiction magazine. “Hunter Emmanuel” is very much a generic story—not in the figurative sense of being predictable or boring, but in the original and literal sense of adhering to a genre.

Mainstream “literary” fiction itself is a genre of sorts. It is largely realistic, largely psychological, and largely preoccupied with the exacting and poetic use of language. As such, I don’t particularly feel like ranking literary fiction as a genre better or worse than other genres. And that's a good thing, because this story seems to be describing a whole lot more than a detective’s investigation of a disembodied leg in a tree, and the woman the leg came from.

This is a story from South Africa, a country that has experienced splits and divisions of many sorts—political, physical, linguistic, racial. Hunter Emmanuel has decided to figure out how the leg was parted from its owner, why one ended up in a tree and the other ended up in a hospital, and what motives might lurk behind all this. If this story were to be taken as a literary allegory, it wouldn’t be hard to posit that the female represents South Africa in one sense or another, while the male detective is an outsider trying to understand divisive actions already completed. But there isn’t quite enough evidence in this story to complete the analogy. All the same, Jenna Bass, the author and filmmaker who has taken Constance Myburgh as her pseudonym, has expressed openness to such interpretation:

I think many films I’ve made, or written, have political elements, even if not on the same level as The Tunnel; I don’t think you can help it if you live in a country where political decisions are particularly visible. At the same time, I don’t like the idea of profiting off of message-based films.

As with films, so with literature, including the stories in Jungle Jim, which she edits herself. There's clearly much beneath the surface of Myburgh's South African-accented prose, and so I hope the continued adventures of Hunter Emmanuel open doors to more conjectural interpretations.

Here's the story as a PDF: Constance Myburgh's 'Hunter Emmanuel'

Check back for a list of the other bloggers contributing to the discussion on this story.

image credit: junglejim.org

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©