Cormac McCarthy, one of the most extraordinary prose writers of our time, spends his days in an office at the Santa Fe Institute, where he types his novels on an Olivetti. As The Chronicle of Higher Education reports, his involvement at the scientific research institute has deepened: McCarthy copy-edited one of his colleagues’ books. “He made me promise he could excise all exclamation points and semicolons, both of which he said have no place in literature,” says Lawrence M. Krauss, whose 2011 book Quantum Man, a biography of Richard Feynman, got the McCarthy treatment.

I started thinking about the equally extraordinary Richard Feynman and his memoir, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, whose title would suffer at least one obvious chop if McCarthy got his hands on it. McCarthy loves dialogue without much attribution or explanation, and his furious-yet-controlled prose—"He was sat before the fire naked save for his breeches and his hands rested palm down upon his knees"—as well as his propensity for extraordinary violence are a far cry from Feynman's excitable, jocular tone: "He didn't know I didn't know, and I didn't know what he said, and he didn't know what I said. But it was OK! It was great! It works!"

But how would the author of Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men, and The Road have edited Mr. Feynman’s book? We offer a suggestion below.

ALL THE PRETTY DISBELIEVERS

OR THE EVENING MERRIMENT IN MR. FEYNMAN'S QUARTERS

1. The Child Fixes Radios by Thinking.

See the child. He is eleven or twelve, he sets up a lab in the house. It is nothing more than a wooden packing box into which he has set shelves, and he has a heater wherein he stokes hogfat and cooks french-fried potatoes day upon day. He also possesses a storage battery and a lamp bank.

The lamp bank he builds with sockets he screws down to a wooden base. When the bulbs were in series, all half-lit, they would glow. Sublime, splendid.

He lights up the bulbs and drives burnished iridescent daggers into the naysayers who come upon his lamp bank. The dead lie by the lamp bank in a great pool of their communal blood. It has set up into a sort of pudding crisscrossed with wires from the storage battery. It has seeped into the floorboards and in between the grooves of the child’s boots. The child surveys the blood and the room and the long slow land around him.

This is great, says the child, and it’s a seller’s market and those lamp banks are only the beginning. Now it’s time to try my hand at radios. He sheathes his dagger bloodred and silvery and walks into the world and is black in the low-set sun, the shadow of evil stretching ever onward behind him.

It was okay, he foams. It was great. It works.

Image: wwnorton.com (sepia effect added)

The fantasy-bots in my iBrain started humming after I read this provocative WSJ essay by Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

Read More

As much as I believe my intuition to be above reproach, it’s nice to have a little science come along to back my shit up. Days after I posted about putting things in boxes, I came across a vindicating Jonah Lehrer article in Wired: it seems that scientists have proven that restrictions trigger the brain to perceive on a larger scale and to conceive of a greater range of ideas, thereby boosting creativity. Thank you, science!

Now that imposing form (aka my favorite kind of restriction) has been sanctified as awesome by the brain masters, I feel compelled to push the envelope a bit further and bring in the frail, curmudgeonly matter of intention. To be clear: by form, I mean the shape of a piece of writing; the way in which content is organized on the page. It's easiest to imagine the imposed form of a sonnet, but any variety of form can just as easily be imposed on any piece of writing. You could set out to write a short story beginning every sentence with the letter Q. You could limit the syllable count in every paragraph, use only monosyllabic words, end every paragraph with a different color.

Now, imagine an idea of what you want to write about and an imposed form are fighting. Do you know who is going to win? Form. The answer is Form. Why? Because form owns you. Because form is more necessary to the achievement of beauty than some idea you had. Form takes that idea and makes it better—science says so.

As soon as an idea finds its way into language, it is trapped by the rules of grammar, coherence, effect. What is written supersedes the idea that compelled the language onto the page.

In other words, what is read are the words put down, not the intention behind those words. No author can whisper into the ear of every reader to explain what they meant. But this imposition, this forcing of an idea into language, in turn allows that idea to be explored, tweaked, and revised more fully. If I get the idea in my head to write about pancakes and how delicious they are, chances are, if I set up some limitations for myself beforehand, if I make the adventure of writing more challenging, I will be forced to enter more interesting territory.

Pancakes could achieve greatness. Pancakes could bring you to your knees. One of the greatest side-effects of form is that it’s likely to push intention further into an unexpected, delightful place.

Photo: coloringes.com

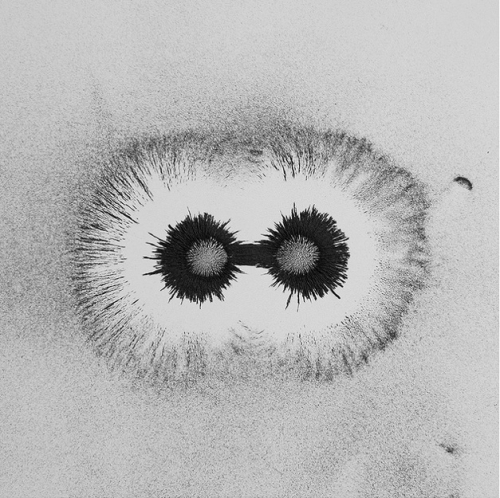

Am I the only one who believes—without hesitation and with no medical knowledge beyond a few Oliver Sacks books—that neurological disorders tell us who we really are? Is anyone else enamored by mind diseases and their relationship to language? Reading through an interview in HarvardMedicine with a neurologist who experiences bouts of hypergraphia (“the medical term for an overpowering desire to write,” as explained in the interview), I suddenly become like a sports fan of the human condition. I cheer and rally. Look at us and how awesomely our brains respond to stress and trauma! Go team!

Alice Flaherty, the neurologist, describes the compulsion as all-encompassing: “That’s all I was conscious of—I had important ideas that I needed to write down because otherwise I would forget them.” What strikes me is her emphasis on documentation, and that the anxiety compelling the act of writing is so entangled with memory. Her hypergraphic writing was not fueled by a desire for self-expression or to engage in communication with others; she wrote so she wouldn't forget.

To me, one of the most fascinating aspects of neurological dysfunction is the idea that they inherently reveal something ancient and essential about human beings. And while no doubt Alice Flaherty’s hypergraphia manifests differently from anyone else’s, is it so outlandish to conclude that writing is a very basic human need? That we are hard-wired not only to form language, but to put that language down in an attempt at preservation? Language can save us!

My monkey brain knows this is true. Putting the words down, the simple everyday act of getting them written, is often what gets us by.

Photo: Rick Friedman for The New York Times

So comparing the phenomena of love to the quantum physics of our cosmos is pretty hackneyed. But over at io9 there is a kaleidomindscope of an introduction to the quantum universe's latest potential matter—spin liquids—that perhaps changes all that.

Read More

Whether it's this past week's earthquake scare or last winter's infamously slow blizzard response, New York is starting to make a name for itself as one of the least-equipped places on earth to deal with, well, earth. As if we needed a bigger test, a category 1 hurricane with a grandma name is now threatening to hit the city this weekend with a force we haven't seen in a couple decades.

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©