We hardcore fans of David Lynch's signature blend of West Coast decay and psychedelic phantasmagoria will lap up just about anything the man brews, so long as it's a moving picture. His “Signature Cup Coffee”? That got mypulse racing! Cooking quinoa? Why the hell not? Amateur meteorology? Bit dull, though granted this is LA weather. Now Lynch ups the ante with a batshit music video for “Crazy Clown Time,” the title track from his 2011 solo album (explored by our own Kayla Blatchley last November).

Clocking in at seven minutes (the approximate length of his classic Rabbitsepisodes), “Crazy Clown Time” is described by Lynch as “intense psychotic backyard craziness, fueled by beer.” No Mystery Man nor Frank Booth, though there's plenty of classic Lynchian imagery to enthrall and confuse us. I invite you to cue up the video and join me as I plunge deep into aMulholland Drive-style puzzle box:

0:01 Lost Highway-like onscreen static (also like Rammstein's “Rammstein” music video, directed by Lynch for the Lost Highway soundtrack)

0:04 engulfing flames, uh Twin Peaks...? (and, by title, Fire Walk With Me)

0:07 distant horizontal shot, used in Blue Velvet's drug den (the Roy Orbison “In Dreams” scene)

0:14 Lynch in profile resembling Eraserhead's Man in the Planet

0:32 woman sprawled on the grass looks vaguely like Masuimi Max, who cameoed in Inland Empire

0:40 from this angle, Bobby (with the “red shirt”) resembles Justin Theroux from Mulholland Drive

Pausing to transcribe a choice lyric verbatim: “Danny poured the beer. Danny poured beer all over Sally. Dannyyyy poured the beer. Danny poured the beer. Danny poured the beeeeeeer all over Sally.”

1:57 Sally starts kicking Danny's ass, a la Inland Empire: that part where Laura Dern and Julia Ormond get in a tussle on Hollywood Boulevard

2:10 choreographed jamming to the beat, ditto a cathartic Inland Empire(plus that red-dress blonde recalls Mulholland Drive's Laura Harring “in disguise”)

2:45 choice lyric: “It was crazy clown time. Crazy clowwwn tiiime. It was real fun.”

3:16 Petey (the '80s punk) lights his hair on fire. Taking a cue from Lynch's description of a painting in his exhibition at Jack Tilton Gallery: “It's our world, and all it is is a boy lighting a fire. And here is his neighbor, the neighborhood girl whom he likes a lot.” As in, quit reading so damn much into it.

4:00 echoes, noises, tape effects, jarring camera movement, i.e. all signature Lynchian elements: Eraserhead on down the line, conjuring strobe-lit frights from previous films (Inland Empire: Nikki confronts The Phantom; Lost Highway's videotape; Mulholland Drive's Club Silencio)

If you've listened to the Crazy Clown Time album track, then Lynch's video is incredibly literal. Lines like: “Bobby, he had a red shirt. Susie, she had hers off completely” become just that, the sorta-Justin Theroux-looking dude pounding back two beers, the blonde woman grinding against a Blue Velvet suburban lawn. This leaves the inclusion of a football player (recalling album track “Football Game”?) and the mustachioed guy on the lawn total mysteries. (Perhaps Twin Peaks kingpin Jean Renault?)

But no matter how bewildering it gets, I am heartened by Lynch's own words in an interview about his artwork:

"You are interpreting it very well yourself. It strikes you a certain way, gives you a certain feeling. And that's it. If there was meant to be more, there would be a whole text for it. It is what it is."

Image: two still frames from Youtube, photo-chopped by the author

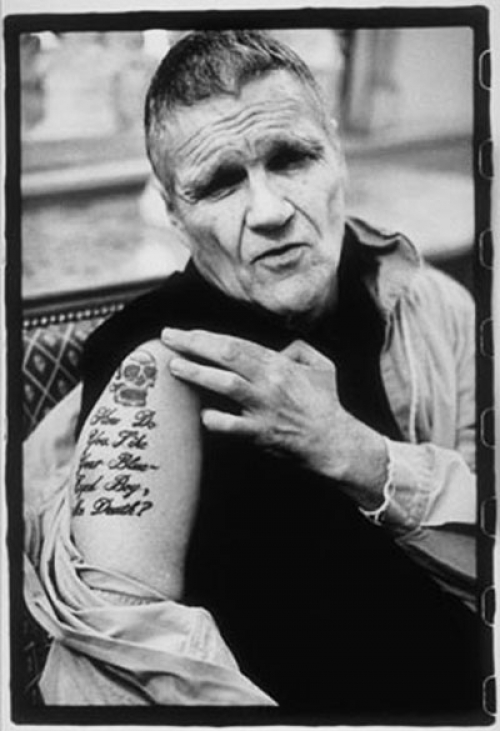

It was with great sadness, and a tremendous sense of unfairness, that I learned of the death of Harry Crews, the Georgia-bred author of The Gospel Singer and A Childhood: The Biography of a Place. The unfairness is somewhat illogical, given Crews’ many years of drinking, fist fights, punishing self-abuse, etc. That Harry Crews should die, even at the age of 76, is not exactly unfair. Nonetheless, we were robbed.

Trying to come up with an appropriate response to my grief-struck sullenness, I decided to take a cue from the man himself. Beyond his literary prowess, Crews was in possession of what I consider to be the very best literary tattoo ever penned and pecked into flesh. On his right forearm, beneath a looming skull, is the ee cummings line, “How do you like your blueeyed boy, Mr. Death?” What better way to pay homage, I thought, than to riffle up some similarly badass literary quotations that would make killer tats? Below is my selection.

It's easier to bleed than sweat, Mr. Motes.

—Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood

Talk into my bullet hole. Tell me I’m fine.

—Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son

What business is it of yours where I’m from, friendo?

—Cormac McCarthy, No Country For Old Men

It wasn’t even me when I was trying to be that face.

—Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

They can’t tell so much about you if you got your eyes closed.

—Ibid.

I am free and that is why I am lost.

—Franz Kafka

Now I can look at you in peace; I don’t eat you anymore.

—Ibid.

But really, you don't have to look any further than Crews' own New York Times obit for killer tat fodder: "Fight On Deadly Rattlers." What other Crews-worthy ink is out there? What tremendously badass quotes should we all brand ourselves with?

Image: coilhouse.net

[In memory of Adrienne Rich, 1929-2012]

First the undergraduate at Radcliffe College, Harvard, fiercely looking out at the world as her manuscript wins the Yale Younger Poets Prize—

Now, careful arriviste,

Delineate at will

Incisions in the ice. (The Diamond Cutters, 1951)

—and a calm but insistent feminist writing history through, for example, Emily Dickinson—

you, woman, masculine

in single-mindedness,

for whom the word was more

than a symptom –

a condition of being.

Till the air buzzing with spoiled language

sang in your ears

of Perjury (I Am in Danger— Sir—, 1964)

—and then a woman, pure and simple, writing capital-H History through her own life—

I am composing on the typewriter late at night, thinking of today. How well we all spoke. A language is a map of our failures. Frederick Douglass wrote an English purer than Milton's. People suffer highly in poverty. ... In America we have only the present tense. I am in danger. You are in danger. The burning of a book arouses no sensation in me. I know it hurts to burn. There are flames of napalm in Catonsville, Maryland. I know it hurts to burn. The typewriter is overheated, my mouth is burning. I cannot touch you and this is the oppressor's language. (The Burning of Paper Instead of Children, 1968)

—and determined to root out truth with her writing—

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

. . . the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth (Diving into the Wreck, 1972)

—and a poet whose poems, as W. H. Auden said, “speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them, and do not tell fibs”—

I am a woman in the prime of life, with certain powers

and those powers severely limited

by authorities whose faces I rarely see.

I am a woman in the prime of life

driving her dead poet in a black Rolls-Royce

through a landscape of twilight and thorns. (I Dream I’m the Death of Orpheus, 1968)

—and herself a multitude of personae, calling herself by turns feminist, intellectual, Jewish, deeply political, mother and wife, lesbian, and yet always human—

If they call me man-hater, you

would have known it for a lie

. . . But can’t you see me as a human being

he said

What is a human being

she said (From an Old House in America, 1974)

—and now an elder stateswoman, her life tempered by death—

Burnt by lightning nevertheless

she’ll walk this terra infinita (Itinerary, 2012)

—unforgettable, unmistakable, a poet whose lines have wrenched open a space for marginalized voices, a poet to whom twenty-first-century letters owes an immeasurable debt.

Image credit: chicagotribune.com

The Paris Review has released their 200th issue, and they have much to celebrate.

Perhaps St. Martin's press can help them do so with their recent surprise delivery.

Suffice to say, they probably won't go to the movies and watch Michael Chabon's John Carter.

Though Chabon could quell any resulting anxiety with a trip to an MFA writing workshop.

You never know what could be brewing in those; possibly the next One Teen Story?

And if all else fails, you can do some comfort cooking with your favorite vegetables.

Photo of detective with narcotics stash / NYDN, 1951

Bowker, an organization that generates (and sells) all sorts of information—logistical, sales, customer preference—about the publishing industry, just released the results of a study on ebook buying habits in 10 countries, “major world markets” all. The study presents a daunting array of data: correlating likelihood to buy with age, gender, and income; predicting increases in ebook sales in certain markets; differentiating pace of growth across regional markets; et ceteraz. There's a lot to say about the study’s intrinsically fascinating details, but what I really like is the flurry of responses popping up throughout the publishing blogworld—and usually revealing way more about the responders than the data.

Lots of the responses smack of confirmation bias. Printing Impressions, a business publication for American printers—who, obvs, want to find hope for pulp-n-fiber books—highlights a post pronouncing that the breathless predictions of ebooks eradicating printed books and brick-and-mortar stores are “way off the mark.” (Although, R.I.P. Borders.) Meanwhile, Digital Book World looks into the morass of data and sees that “the world has caught up to the U.S. when it comes to e-book buying.” On the internet, everyone wins! But where do I get my ice cream?

And then there are the thought-tickling observations. At MobyLives, Kelly Burdick was struck by the fact that both the French and the Japanese seem less than enthusiastic about purchasing ebooks. French insistence on the sensuous pleasures of reading a bound book? Or, as Burdick suggests, simply a result of the Amazon ebook store being relatively new in France? Time will tell; there’s nothing in the current study to say. Other people found other things significant. And more people will likely write more, shortly: watch them do it, in real time!

That’s the thing about studies like this one. Bowker generated so much data, and then correlated it in so many ways, that without some sober (boh-ring!) statistical thinking, extrapolations begin to look meaningless. They suggest that data can be bent to support virtually any argument. Which means these broad interpretations may reveal less about what’s going to happen with ebook sales and more about what the people jockeying the data want to believe.

For my part, I find it interesting that India leads the globe in percentage of people who have purchased ebooks: I want to see that correlated with pricing in Indian ebook outlets, access to old-fashioned print books, and availability of ereaders, as well as some remarks about the culture of the book in the subcontinent.

I could avail myself of Google and the lieberry. Or I could take my cue from the blogosphere: extrapolate first, ask questions later.

Image via flickr user Josh Bancroft

[The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard is out today from the Library of America. In homage to his singular writing, I’ve decided to create an “I Remember” of my own.]

I remember picking apples at Eckert’s orchards.

I remember waking up in the wrong bed entirely.

I remember trying on hats with my sister.

I remember reading Joe Brainard for the first time. I thought I Rememberwas a joke at first, then a wistful way to look at the world, then the only way I should look at my life.

I remember tearing a marigold out of our garden because I thought it was just a weed. My mother was so upset with me, even though she knew it was a mistake.

I remember when I got into college. There was a thin envelope, and the words didn’t say “we regret,” so I couldn’t understand it and I had to give it to someone who could read it to me.

I remember the first real date I went on. The first real date, when neither of us were trying to be grown-up or impress each other. Three hours later, I didn’t want it to ever end.

I remember learning how to make crêpes.

I remember making them far too often after that until everybody was tired of eating them.

I remember my first and my last cigarette. I got bored and gave it back to the friend who had let me try it.

I remember flipping the light switch up and down until I was able to hold it at exactly the point to make the whole room very dim but still lit.

I remember when I figured out that I’d never had Brussels sprouts in my life, ever. Then I told my mother that was one thing she had done right.

I remember watching Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining with my little brother on Halloween weekend: him petrified as the suspenseful music rose and rose, and me bored as I couldn’t hear it.

I remember setting the hands into the face of a clock I’d made out of wood. It’s still on the wall at home, ticking away.

I remember all six warts I had on my fingers (three on my left pointer finger alone).

I remember learning that Lucian Freud had died and recalling first that one of my close friends called him her favorite portraitist ever, and second that he had offered to sketch the actress Joan Collins about which she wrote, many years later: “To my great regret, I said sorry, no, as I had to get back to my afternoon studies.”

I remember a ten-foot-high inflatable globe that I stepped into. I couldn’t find any of the countries because I was looking at the world inside-out.

I remember watching the first season of Lost on DVD, and realizing three days and twenty-five episodes later that I was completely hooked.

I remember every house I moved out of.

I remember, I do remember.

Image credit: joebrainard.org

The plaintive, kazooish earworm that is Megan Draper’s performance of “Zou Bisou Bisou” in the season five premiere of Mad Men has been burrowing into the hive brain for the last two days. AMC even released it as a single on iTunes. What is really enchanting, though, is the see-through sleeves she dons (sorry) in her dance of the seven drapes (really sorry), and the “huge undergarments” in which she concludes her performance of the episode. You may be surprised to know that Immanuel Kant has some ideas about huge undies, while Eve Sedgwick offers us the definitive word on the veil. My Mad Men prediction, if you can’t tell, is that Don will murder Megan. I have a fresh perspective: Sunday’s was the first episode I’ve seen.

1.

Q: Speaking of costumes, tell me about the lingerie you wore in the "house cleaning" scene...

A: It's vintage stuff. It's funny, the scene is so risqué...but it's like the hugest undergarments. I mean, it's quite large. It's not very skimpy.

—Mad Men’s Jessica Paré, aka Megan Draper, is interviewed after the premiere of the show’s fifth season, in which she performs a “light burlesque” version of Gillian Hills’s 1960 hit “Zou Bisou Bisou,” and cleans her apartment.

2.

“…The attributes of the veil, and of the surface generally, are contagious metonymically, by touch, and that a related thematic strain depict veils, like flesh, as suffused or marked with blood…The veil itself, however, is also suffused with sexuality. This is true partly because of the other, apparently opposite set of meanings it hides: the veil that conceals and inhibits sexuality comes by the same gesture to represent it, both as metonym of the thing covered and as a metaphor for the system of prohibitions by which sexual desire is enhanced and specified…Note, though, how much the veil is like the veiled, the flesh that is prized for its ‘dazzling whiteness’ (the phrase occurs formulaically). The flesh, moreover, seems valueless without the veil.”

—Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “The Character in the Veil,” an essay about Gothic Literature from 1981.

3.

“The Platonizing philosophy of feelings never exhausts its supply of such figural expressions, which are supposed to make that intimation comprehensible; for example, ‘to approach so near the goddess wisdom that one can perceive the rustle of her garment…since he cannot lift up the veil of Isis, he can nevertheless make it so thin that one can intimate the goddess under this veil.’ Precisely how thin is not said; presumably, just thick enough that one can make the specter into whatever one wants. For otherwise it would be a vision that should definitely be avoided.”

—Immanuel Kant, “On a Newly Arisen Superior Tone in Philosophy,” (trans. Peter Fenves), 1796.

Here's the video of Paré's performance: Un, Deux, Trois, Quatre!

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the lavalamp, gaslight, candlelight, campfire, torch, sometimes even the starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The form of the column strives to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” Each week you will find here some citational constellation, offered with astonishment and without comment, that can serve as an end in itself, dinner party fodder, or an occasion for further thought or writing. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

Image via AMC

I was walking down the Upper East Side as evening came on. I turned the corner and saw a familiar face: quirky haircut, aquiline nose. We walked toward each other, and I noticed his slightly-too-large ears. Our eyes locked for about two seconds—“a look of glass,” just too long for it to be a random glance on the street—and then (to keep borrowing from John Ashbery) I walked on shaken: was I the perceived? Did he notice me, this time, as I am, or was it postponed again?

I had never met him, nor he me. I had heard his name in vague contexts: he was the friend of a brother of a guy I’d barely known back home. And he was what, five years older than me? How would I have introduced myself to him? We were just from the same part of the Midwest! Still, I had looked him up on Facebook when I'd moved to the city, whereupon I learned that we didn’t have any mutual friends. So I stopped wondering about him. And then I saw him on the street.

I walked on shaken: was there anything I could have said, really, at 5:20 in the afternoon in the middle of a crowded intersection? That moment could have only happened in the twenty-first century. This is the age of the Internet, and we’re all voyeurs, for better or for worse. I keep thinking about how Facebook’s Mini-Feed legitimizes this: I can just mention something I shouldn’t have known, and claim I saw it on my Mini-Feed. But I had no way that I could say I knew him; there was no Mini-Feed keeping us apprised of each other.

I’m more interested in this moment than in the novel I’m working on. It's more honest. Which is why, after the Canadian author Sheila Heti had gotten tired of imagining characters and stories when her actual friends were more vivid and interesting, she had decided to write How Should a Person Be? The book is a pastiche of conversations, emails, philosophical thoughts, and other mishmash centering on her friends. It’s strangely appealing. Her book is a model of the twenty-first century first-person narrative: not a neatly closed-off story, nor a megalomaniac epic that attempts to swallow the world whole, but a clear and direct record of the world as it is, as it goes on, without the artificial struggle for narrative structure.

Making sense of this encounter is my way of finding a new kind of closure. My friends were puzzled that I never went up to him and asked him if he was from the Midwest, too. I wasn’t so bothered, just surprised. I’ll probably see him again somewhere, at a party or a bar where it makes sense to say hello. And if I never see him again, well, I suppose I never actually knew him.

Image credit: journeyphotographic.com

“I'll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination,” writes the narrator of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness. It’s story set on a faraway planet named Winter, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the narrator's “homeworld” was planet Earth.

We live in a time and a place where we watch Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert for the news, where we relish the scandal of James Frey making up his memoir but gasp at Kim Kardashian getting divorced after a multi-million-dollar wedding that depicted a perfect couple.

If someone fudges the facts and fesses up, that’s not such a scandal. But if we figure out that we’ve been lied to...hoo boy.

This American Life recently released an episode retracting Mike Daisey’s reportage, on a previous broadcast, of the labor issues in China's Apple factories. The process of discovering the falsehoods in Daisey’s story recalls that of the people who managed to get beneath the veneer of Stephen Glass, the ambitious young journalist at The New Republic who was caught fabricating quotes, sources, and entire stories. In both instances, the recalcitrant writer at the center devolves the quest for truth into a game of he-said-she-said.

And yet, when John D’Agata goes back on himself in About a Mountain andLifespan of a Fact, he doesn’t outrage us. He tells us that he’s lying, so we can forgive him the lie. And when David Sedaris embellishes his family tales, nobody seems quite as infuriated.

The dividing line is unmistakable: one one side, we have the author telling us that he lied; on the other, we find out that he lied. It's the difference between a an amused, engaged reader and a disgruntled one.

Truth is a matter of the imagination. But even animals can lie—so what use is the truth, as we mutually perceive and imagine it?

“The truth” is exactly as useful as the words we speak to communicate with each other. We understand each other because we agree on what the words of our language mean, and how their syntax creates meaning. If the rules changed, we would still be able to talk, so long as we all knew what had changed. But when we choose to disagree on what “really happened,” the disconnect can be traumatizing.

Mike Daisey says, rightly, that “This American Life is essentially a journalistic—not a theatrical—enterprise, and as such it operates under a different set of rules and expectations” from his theatrical performance, but his statementcomes far too late. We can’t trust someone who evidently refuses to play by our rules. Humans are a social species, but we can only be social so long as we share—the words of our language, and the manifold, contradictory, and deeply necessary figments of our collective imagination.

image credit: Will Temple via flickr.com/photos/grubbymits/5352592011/

In the wake of The Lifespan of a Fact and the agony of Mike Daisey, The Awl has rounded up almost a dozen quotations on David Sedaris and his often slippery handling of facts. Reading them, I realized that this issue had been more or less settled in my mind since I heard him read "I Like Guys" on This American Life—a recording that begins...

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©