Move over, Cool Britannia, the Olympics have taken London by storm. And when something this crazy happens, everybody's got some thoughts. Including Banksy. Especially Banksy, the world's most famous graffiti artist. Here's the latest swiped from his site (just in case the IOC scrubs away his graffiti), and annotated by the Black Balloon commentariat:

1. [Javelin Thrower with Fully Functional Rocket]

Note the poor form, likely inspired by Hellenistic Greek sculptures rather than contemporary photography of javelin throwers, which wouldn't get the rocket (or javelin) very far. Consider the jersey number, which likely may refer to the gold medalist for the 2004 Olympics women's javelin competition, Osleidys Menendez from Cuba. What can we make of the fact that this winner has been depicted as a white male? Is this an incitement to the athletes to make war, not peace? Or is this a reference to the militarization of Britain, and the sudden arrival of military troops to provide overly thorough security for this event?

2. [Pole Vaulter Over Barbed-Wire fence, with Old Mattress]

Again, the form is terrible: the body should go straight as it lets go of the pole, as this video shows. Even more unnervingly, the vaulter seems to have dramatically overshot the height of the barbed-wire fence, instead of barely surpassing it. Is this England trying too hard to make a spectacle of itself? Is this the organizers grossly overstepping their bounds? The mattress, at least, makes sense: once the Olympics are over, what will remain? Plenty of trash, that's for sure. But hey, I like the creative use of found materials. Nothing says austerity measures like using a dirty mattress.

3. [Sweatshop Worker Making British Flags]

If this is an allegory, we had better pay close attention: who are the sweatshop workers here? Are they as young, and as naive, as the child here? One of my friends sent me this video of Olympic diver Tom Daleybeing doused in glycerin for a photo shoot—and he's barely eighteen. Does the United Kingdom depend entirely on the young, the fresh, and the novel to establish itself? What's happened to history, to everything that makes London different from any other city that has hosted the Olympics?

I'm sure this isn't the last of it. I'll be watching the Olympic competitions all this week, and I'll keep my eyes peeled for more of Banksy's biting commentary. May the best man win.

I haven’t been a lifeguard for years. But when I walk past the freshly reopened McCarren Park Pool and get a whiff of chlorine, I realize there are some things I haven’t really forgotten. The positions for performing CPR. The office cubbyholes where we stashed our keys while on duty. The way the light on the water changes from six o’clock, when the sun starts setting, until the pool closes at eight.

To the children in the water, we are like the gargoyles on an old cathedral: instantly recognized, immediately forgotten. If we are gargoyles, they are wide-eyed pilgrims, in love with water. They swim with inflatable wings, water noodles, kickboards, flippers. They swim in the shallow areas, then they go deeper, then they learn how to dive. We watch them come back over days, months, years.

We perform the same rituals day after day. We unlock the bathhouse doors. We hand each other our foam rescue tubes as we climb up and down the lifeguard stands. We loosen the lane ropes, turning six-foot-tall wheels, until they have been coiled up on a reel aboveground, only to unroll them again later in the day.

The water circulates through the filters and the pumps, always the same water.

• • • •

One winter, I went to the Whitney, and saw a series of photographs by Roni Horn of the River Thames. As I looked more closely, I realized that the pictures had been superimposed with tiny numbers. Below the photographs were numbered footnotes.

61. Is water sexy?

62. Water is sexy.

63. Water is sexy. It’s the purity of it, the transparency, the passivity, the aggression of it.

64. Water is sexy; the sensuality of it teases me when I’m near it.

65. Water is sexy. (I want to touch it, to hold it, to drink it, to go into it, to be surrounded by it.)

66. Water is sexy. (I want to be near it, to be in it, to move through it, to be under it. I want it in me.)

I smiled. Not long after, I forgot about the photos and their captions, just as I stopped thinking about about my time as a lifeguard. Even when McCarren Pool opened last month, I didn't think about the water as anything more than an afternoon's diversion.

• • • •

Back when I was a lifeguard, I had always kept an eye on the evening swim teams practicing. After a shift, I sometimes jumped straight from my chair into the water and started swimming laps beside them. I swam to shake off the heat and restlessness of the long day, to bring my mind back to the real world I would face upon exiting the water. Watching those swimmers, I wondered what they thought about as they went from one end of the pool to the other. And then I read Leanne Shapton’s Swimming Studies.

I know their hours of swimming are no less repetitive than a lifeguard’s on his chair. Instead of focusing on everyone but themselves, however, swimmers focus on nobody but themselves. Leanne Shapton distills this to a state of mind.*

I swim a few laps, then decide to do a hundred. This is my default workout, one hundred reps of whatever. One hundred is actually not much, but it sounds nice, like “an hour,” even though swimming a hundred laps of this short a pool does not take an hour, it takes about twenty minutes ... As I swim, my mind wanders. I talk to myself. What I can see through my goggles is boring and foggy, the same view lap by lap. Mundane, unrelated memories flash up vividly and randomly, a slide show of shuffling thoughts.

Leanne had been training for the Olympics. She nearly qualified, but didn’t. I wasn’t interested in reading about this, nor she in writing about this. Instead, I read about the small, quotidian details of a swimmer's life. Her drives with her parents to and from the pool. The effects chlorine has on swimmers’ swimsuits, on swimmers’ hair. And then there are her watercolors. She continually detailed the contours of the different pools she had gone to—a silly thing to mention, I thought, until I came much later in the book to watercolors of all the swimming pools she remembered, and I suddenly recognized the details she had described.

Leanne stopped seriously competing after those Olympic trials, channeling her energy into art. The result, in Swimming Studies, is a collage of prose texts and pieces of art that cumulatively feel well, watery. Aqueous. The quality of her diction, as well as the similarity of the many scenes she depicts, makes reading the book feel very much like swimming laps with someone who knows the pool, the water, and her own body, extraordinarily well.

• • • •

I was a lifeguard. And Leanne, the one in the water, was just as obsessed with its surface. She went through rubber swimming caps, through championships, through boyfriends and houses and cities, and still relished each moment she made the first dive into the sickly-blue water. I looked through the footnotes about her swimsuits, and was reminded again of Roni Horn’s pictures.

Sure enough, those photographs had been made into a book: Another Water (The River Thames, for Example). Roni's footnotes were still as idiosyncratic and meditative as back at the Whitney.

411. Water shines. Water shimmers. Water glows. Water glimmers. Water glitters. Water gleams. Water glistens. Water glints. Water twinkles. Water sparkles. Water blinks. Water winks. Water waves.

412. Under the cover of harsh, elusive colors, black is constant. These useless, hopeless colors gather around this black place.

413. The Thames is a tunnel.

414. The river is a tunnel, it’s civic infrastructure.

415. The river is a tunnel with an uncountable number of entrances.

416. When you go into the river you discover a new entrance—and in yourself you uncover an exit, an unseen exit, your exit. (You brought it with you.)

There are many waters, but our experiences with them were deeply similar, deeply meditative. I looked up from each to realize that I did not smell chlorine. I was not in a lifeguard chair in the Midwest or in Brooklyn but on a couch in my apartment. These books had so perfectly recreated in my mind the experience of sitting at the edge of water that those faraway summers had come back and, doing flip turns, splashed me awake.

* Buzz Poole, who also works at Black Balloon and was once a competitive swimmer, has a wholly different and very enjoyable perspective on Shapton's book at The Millions.

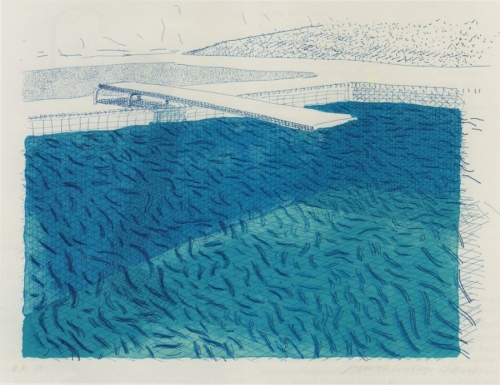

Image credit: David Hockney, Swimming Pool Lithograph,ahholeahhole.blogspot.com

On July 27, the Olympics will start in London. My friends there are actually going elsewhere for the full three weeks of tourist and media frenzy. They just want to enjoy their summers, and watch the occasional swimming match on TV.

They’re also escaping the most Orwellian set of circumstances I’ve heard about in ages. Kosmograd, whose handle recalls a formerly totalitarian country, describes the rise of the “Brand Exclusion Zone,” which stringently enforces brand purity for the Olympics’ official sponsors. The goal is to prevent ambushes by other brands and to restrict brand exposure solely to companies that have paid millions of dollars and pounds and euros for advertising rights.

As a result, visitors wearing clothing or carrying items with the logos of rival brands will be barred from entering the games. Athletes and spectators are not allowed to upload videos of their own, which would compete with television broadcasts. These restrictions exist in both space and time, “up to 1km beyond [the Olympic Park’s] perimeter, for up to 35 days.”

Freedom of speech is a popular right, and one of the most easily contested. The issue becomes even more complicated when companies and individuals clash. But in this case, I feel uncomfortable at how rigidly the IOC is suppressing other voices. And when I think of the tyranny of brands, I think of Banksy:

“Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. You can do whatever you like with it. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head. You owe the companies nothing. Less than nothing, you especially don’t owe them any courtesy. They owe you. They have re-arranged the world to put themselves in front of you. They never asked for your permission, don’t even start asking for theirs.”

(Viz the graffito by Criminal Chalkist, above, of a vigilante running off with one of the Olympic rings. I presume the IOC ordered all graffiti removed shortly thereafter.)

It’s true that London competed with many other cities to host the Olympics in 2012. They’ll benefit from the extraordinary influx of money, from the massive public works projects and increased media visibility. But at what cost? What will be lost by accepting the IOC's draconion rules?

When I read George Orwell’s 1984 in high school, I was fascinated by its ironies: the Ministry of Peace keeps Oceania at war, even the Ministry of Truth perpetually lies to maintain a consistent history. I took heart in how the very final page, an essay about that regime’s language, was written in the past tense. But here we are in 2012: now the Brand Exclusion Zone maintains brand purity by constantly fighting off other brands, and polices the Olympic athletes’ own Twitter accounts for brand infringement. What role have we played (and should play) in this fulfillment of Orwell's prophecy? How is it that London, the fictional capital of Airstrip One in1984, has let itself be seized in real life by Big Brother?

image source: kosmograd.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©