I used to love going to the monastery on the shores of the sea. Its whiteness thumbed its nose at the blue, it burned eyes at noon, while in the evening the shadows of the cypresses crept over it. The old folks said that the monastery was a gift from a rich man. Once, when a terrible storm overtook his ship, he promised St. Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors, that if St. Nicholas saved him, he would build a white stone church on the cape. St. Nicholas saved him, and since the stone in that region was gray, the man imported carved white stone all the way from Greece.The monastery and church of St. Nicholas gleamed white in the distance, filling the sailors passing by the cape with hope, since all the winds and currents really did meet there.

In the sheltered flagstone-paved inner courtyard there was a long wooden table around which the nuns gathered in the summer and early autumn to do their canning for the winter. “Tomato time,” that’s what they called it, and they were happy when I used to come with my grandfather to help them with the grape harvest, or with the apples, pears, and plums in the garden.

The abbess, Mother Efrosinia, was a sprightly woman. She would read the Bible to me and explain the parts I didn’t understand. Sometimes we played hide-and-seek. She sang well in church and had a low, strong voice. She loved standing at the edge of the cliffs, looming over the sea, and although she was physically there, in fact she was elsewhere. In her habit, she looked like a tree struck by lightning; she wore her towering velvet hat, or kamilavka, tied with a black veil. She had a calm and cheerful soul. Her eyes had turned bluish-green from staring at the sea, but when she was angry, she glared dark green, and it was best to make yourself scarce.

Besides the five older nuns, there was also one new, young novice with a round white face. She was serious and somehow seemed affronted. She looked down, kept silent, and was always reading. I didn’t like her and felt uncomfortable in her presence. A stern and merciless God watched me through her olive eyes and knew all of my past and future misdeeds.

Ever since he had donned his doorman’s uniform with its epaulets, Grandpa had also been looking after the monastery garden. The oxheart was ripening. This year the tomatoes were growing by the cartload and they could barely manage to pick them all. The nuns crossed themselves and thanked the Almighty. The monastery was famous for its tomato soup.

Tomato Soup

In one quart of salted water, thoroughly boil a finely chopped head of celery, three carrots, one pepper, three onions, and two green onions. Strain out the vegetables. In this broth, bring the juice of five grated tomatoes to a boil, along with two nests of vermicelli, a sugar cube (to soften the tomatoes’ tart taste), a small cone of incense crushed into powder, and whole basil leaves. Can be served with grated cheese.

Whole cauldrons simmered, especially on holidays, no matter what the season. If it wasn’t fasting time, the nuns would add cheese to the soup. On the table stood small pots of hot pepper paste, which Sister Evdokia concocted all by herself.

In one quart of salted water, thoroughly boil a finely chopped head of celery, three carrots, one pepper, three onions, and two green onions. Strain out the vegetables. In this broth, bring the juice of five grated tomatoes to a boil, along with two nests of vermicelli, a sugar cube (to soften the tomatoes’ tart taste), a small cone of incense crushed into powder, and whole basil leaves. Can be served with grated cheese.

Whole cauldrons simmered, especially on holidays, no matter what the season. If it wasn’t fasting time, the nuns would add cheese to the soup. On the table stood small pots of hot pepper paste, which Sister Evdokia concocted all by herself.

Evdokia’s Hot Sauce

Boil a pound of finely chopped, extremely hot peppers in two cups of water. Mash through a sieve. Add the following to the resulting purée: a half-cup of brandy, three spoonfuls of sugar, the juice of one lemon, salt, and, if needed, another cup of water. The sauce can be seasoned with finely chopped basil or ground cumin, as desired.

Boil a pound of finely chopped, extremely hot peppers in two cups of water. Mash through a sieve. Add the following to the resulting purée: a half-cup of brandy, three spoonfuls of sugar, the juice of one lemon, salt, and, if needed, another cup of water. The sauce can be seasoned with finely chopped basil or ground cumin, as desired.

People from the nearby villages who came for the holiday would eat soup, cry from the hot sauce, and put out the fire with the convent bread’s thick crust and cold water from the spring—and sometimes with wine, too, if Mother Superior allowed it. The red soup made everyone loquacious and cheerful.

One day, at the start of tomato time, Grandpa and I set off around noon in the dog buggy. We had two giant wolfhounds that he hitched up to a cart just big enough for two people and a little luggage. The people in Nesebar had gotten used to my grandfather’s eccentricities, but that dog buggy made him famous throughout the whole region. Boris had thought up this mode of transportation when he took over a pigsty in the village of Vlas, using the buggy to cart over the swill. Otherwise, he usually scooted around on his bike. The pigsty as an enterprise had come about when my mother’s younger sister, Sara, wanted to study agriculture and had to have experience with farm work in order to apply. Grandpa installed some yahoo named Boncho with the pigs as a watchman, and he and Sara started up the pigsty in Vlas. Boris went around to the restaurants in Sunny Beach in his dog buggy, collecting slop in pails. Boncho kept watch over the pigs and got tanked, and, whenever he got hungry, helped himself to the least mangy meatballs from the slop. From time to time, Grandpa also found some horse on its last legs so the pigs could have fresh meat. Once, they brought over a blind, unfortunate horse. The pigs were hungry. Boncho was dead drunk. What else could Sara do? She tossed a sack over its head and whacked it with the butt of an ax (while looking the other way, of course). Afterward, once she had made sure it wasn’t moving, she chopped it up. The pigs went crazy for it.

My aunt completed her internship, but never did end up studying agriculture, because right when she was supposed to apply, she fell in love with a handsome German choral director and, to my grandmother’s great relief, got married and moved to Germany. More to the point, this was a great relief because Sara was a beauty and had my grandmother’s wild nature. Hordes of admirers were always traipsing after her, and that “threatened the family’s good name.” My aunt’s marriage in Germany was a particular source of pride for Nikula, something like an emblem of the family’s success. Every summer, Sara would come and visit us with suitcases full of presents and her experiences abroad, with which she strengthened her belonging to the family.

It was fun traveling by dog, to say nothing of how proud I was to sit next to Boris in that strange vehicle. That day, when we reached the monastery, Mother Efrosinia had just finished parceling out the tasks. Grandpa disappeared somewhere into the garden. Around the big table under the vine-covered trellis, the nuns were working silently, as if speaking would make the tomatoes go sour. They were making tomato juice; peeled, canned tomatoes cut into large chunks; and thick tomato sauce with celery, parsley, and chili peppers in taller jars. They lugged over tubs of tomatoes; a huge cauldron of water was boiling on the fire so they could steam them for a few minutes right in the tubs to make the skins come off easily. After that, they peeled the tomatoes, cut them into large chunks, and stuffed them into the jars. Granny Petrania sealed the lids with a little machine. Her moustache was longer than Grandpa’s.

Afterward, the full jars were arranged in a big black kettle, where they would be boiled for ten minutes. They gave me a sharp little knife so I could peel tomatoes, too. The young novice usually did the same job, but that time there was something wrong with both her wrists and they were bandaged up. She sat at the end of the table, clutching a small Bible, and from time to time would stop perfectly still, her gaze empty.

I adored holding a warm, stretched-to-bursting tomato in my hand. I had my own system for peeling them. First, I made a little cross on the back- side and from there pulled each corner of red skin toward the green navel. After that I would cut the naked tomato into quarters and toss it into a big wooden trough. I was important. I was working right alongside the grown-ups. Sometimes, it seemed like I could hear the red juice pulsing in our veins. The wind, gentle and round there in the monastery's inner courtyard, rustled in the trellis. Its shadows played on our faces. From time to time, I noisily slurped up the thin streams of juice that trickled all the way down to my elbows, or ate the tomatoes whole when little ones came my way.

At the other end of the table, Evdokia stuffed the peeled tomatoes through a meat grinder for juicing. Her strong white fingers pressed them into the machine’s insatiable throat, and I kept thinking that any minute her flesh would come out of the little holes, but she always managed to save her fingers and even licked them from time to time, eyes closed. Evdokia was the liveliest and cleverest of the nuns in the monastery. Her husband had been lost at sea during a storm, and her sons had run off to America. The authorities had dragged her in for interrogation after interrogation, and in the end finally left her alone. Then, to everyone’s astonishment, she joined the monastery. She was pretty, with warm white skin and light-brown, almost yellow eyes. Instead of black, she wore a tidy dark blue habit that reached below her knees, and when she worked in the garden or at the big table, she put on a green apron with big orange flowers. Unruly copper curls often tumbled out from beneath her dark blue veil. I greatly envied her for that hair and dreamed that when I grew up, I would dye mine that color, too.

Petrania handed me a longish little tomato, and in my greediness I bit into it so ferociously that the seeds shot out and sprayed Mother Superior. Efrosinia blinked through the goo, covered in yellow seeds. I started to laugh, but the young nun shot me an angry glance.

“Ooh, Mother, it was an accident, I swear,” I started apologizing, diving under the table to clean her up.

“Don’t bother, my child, I was going to wash this habit anyway.”

Then I noticed that right in the middle of her velvet kamilavka, the seeds had formed a perfect little cross.

“Mother, look. You’ve got a tomato cross.”

“Holy Mary, Mother of God!”

The nuns crossed themselves. Mother Superior raised her eyebrows knowingly and smiled. Evdokia dumped yet another overflowing tub of tomatoes on the table.

“Mother, why do we cross ourselves?” I asked. “Didn’t they crucify Christ on the cross? So that means the cross is something bad.”

Mother Superior looked at me carefully and started to say something, but the young nun’s voice cut in: “The cross is a symbol of the soul, crucified by the human body. The soul strains upward, but the body drags it back down to earth.”

“But why did people kill God?”

“He is the Son of God,” the young nun replied. “He was sent especially to earth so that through His sacrificial death man would be redeemed from his sins.”

“So how can one person dying forgive everybody’s sins?”

“Didn’t I just tell you that He’s not just one person, but the Son of God, who loved us so much that He sacrificed Himself for us and thus washed away our sins?”

“People are still bad today. He sacrificed Himself for nothing.”

“You don’t know how much worse things would be if He hadn’t sacrificed Himself. The power of His love is great,” she snapped.

“So does everybody who loves have to sacrifice themselves? If He loved us, why did He let them crucify Him? Couldn’t He just have lived with us and loved us, instead of dying?” I insisted.

“He couldn’t, because people are constantly tempted by the devil and they always commit sins. With His sacrifice, the Son of God weakened the power of evil. We are not worthy of Him.”

“How did He weaken evil?”

“Oooof, Manda, you’re too little to understand,” the young nun shouted in an unexpectedly loud voice.

Mother Superior shot her a dark-green glance. I took this as reinforcement and pressed on. “So since Christ suffered, are only those who suffer good?”

“No, good people are all those who . . . ,” Petrania started to explain.

“In that case, Grandma’s good, because she’s always suffering, while Grandpa is bad, because he’s always out having fun.”

“Your grandfather is tempted by the devil,” hissed the young nun breathlessly, looking Evdokia straight in the eye. Flustered, the latter lowered her gaze.

“. . . believe in the true faith,” Petrania concluded.

The nuns waited to see how this unequal theological debate would end. Mother Superior continued filling the jars. In the intervening pause, I finished off my volley. “Grandpa isn’t bad. He doesn’t beat me.”

“Look, my child,” Mother Superior began in her deep voice, “a person wants to be good, but he is not bound to good alone. He can choose both to sin and to suffer. Choice is what separates us from the animals and brings us closer to God.”

The table under the vines fell silent. I got the feeling that I was getting into something I didn’t understand. I felt the truth somewhere within myself, but I couldn’t express it. I started itching all over. I felt confined and I wanted to jump or run, so I told Mother Superior I was going down for a swim. Efrosinia nodded.

As soon as I poked my nose out of the monastery, the wind struck me. I closed my eyes and gave myself over to it. I blew through the branches of the almond trees, floated above the water, I was the soft grass on the hills, and at that moment, I knew.

I took off, running down the steep path to the sea. I dived in, dress and all, so as to wash the red juice out of it, then flopped down naked on the hot sand. Good thing it was a dark blue print with little violet roses, so the red didn’t show much. I wore it when I went to the monastery, because once the young nun had said that it wasn’t proper to tramp around the cloister in my underpants, as was my wont. I went back into the water. I really loved diving at the cape. Marble columns from some old temple gleamed on the sea floor, and there were huge, completely preserved jars in which all sorts of creatures hid. When I pounded on one of the jars, a silver wine of thousands of tiny fish frothed from the inside. I had just taken a breath to dive back down to the jars when from up above I heard my grandfather’s piercing whistle. Only he could whistle like that; I envied him terribly for this. I was also a good whistler myself, so much so that when I got lost, which happened all too often, my grandpa could find me by my whistle. I swam toward the shore and, wet as I was, pulled on my dress, ironed out by the sun and the salt, and climbed up the steep path to the monastery.

Up above, Grandpa was lining up gifts on top of his old quilted jacket in the wooden cart—a bottle of amber plum brandy, a jar of hot chilies with tomato sauce, a basket of yellow pears, and ears of corn. Evdokia came running over carrying a loaf of bread with a little cross baked on top, waved goodbye to us, and we started bumping along the narrow dusty road through the almond forests—which made eating the corn really difficult.

At home, Nikula took one look at the gifts and knew we’d been to see the witches again, as she called the nuns. She tossed aluminum plates filled with leftovers on the table and sat silently somewhere on her beloved porch. Grandpa winked at me, and I went to pick some of the hottest chilies for him and some of their babies for me. When I got back with the peppers, he had already cracked open a big head of garlic.

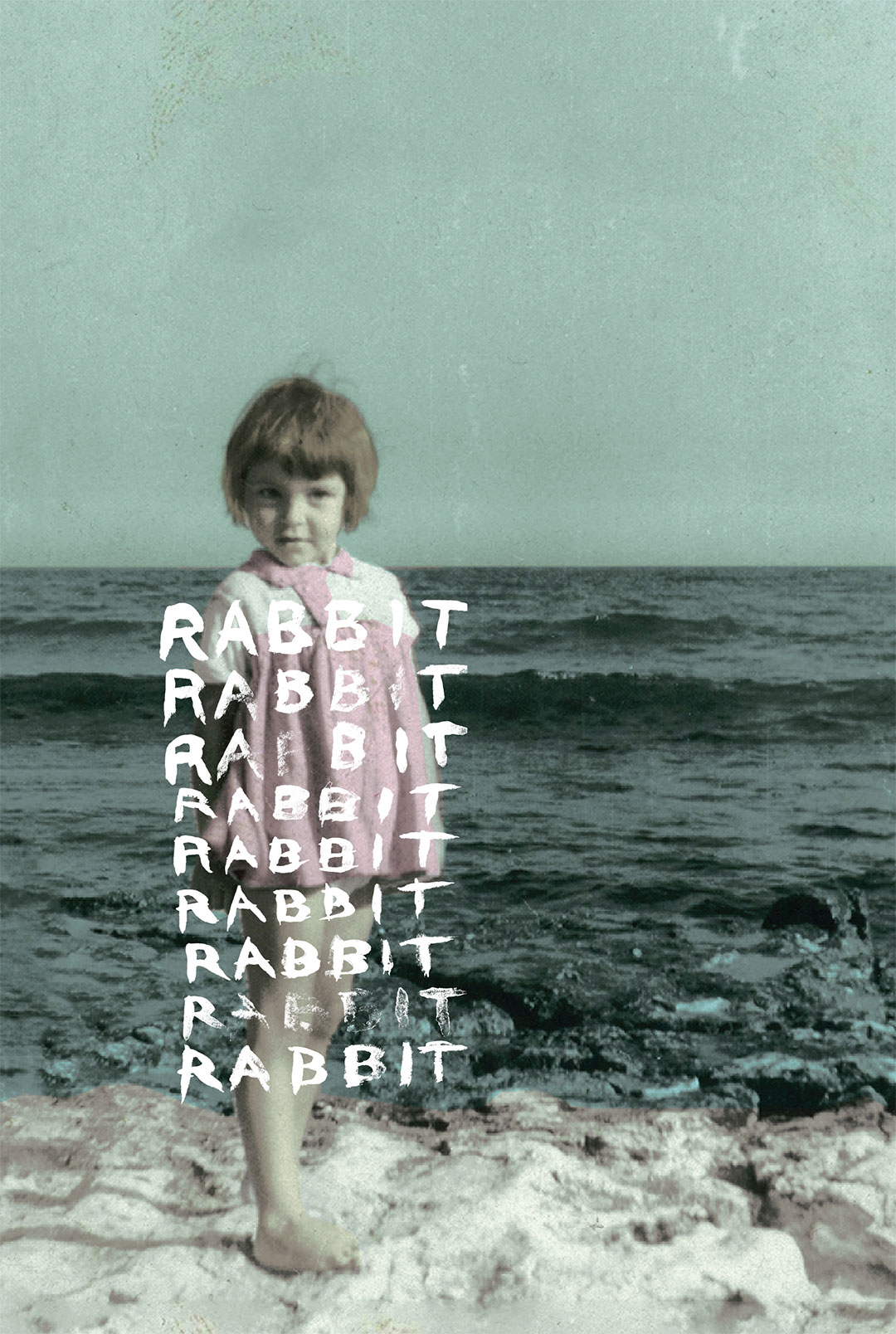

Author Virginia Zaharieva was born in Sofia in 1959. She is a writer, psychotherapist, feminist, and mother. Her novel Nine Rabbits is among the most celebrated Bulgarian books to appear over the past two decades and the first of Zaharieva’s work made available in North America.

Translator Angela Rodel won a Fulbright fellowship to study Bulgarian at Sofia University in 1996 and returned to Bulgaria on a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship in 2004, where she still resides and works as a literary translator of note. Rodel won a 2013 NEA Translation Grant for Georgi Gospodinov’s novel The Physics of Sorrow and a PEN Translation Fund Grant for Holy Light, a collection of stories by Georgi Tenev. In both cases, this was the first time a Bulgarian work had received the award.

Images: ©Janelle Jones/Black Balloon Publishing