August 6, 1945: An air raid siren was not, in itself, a reason to panic. Mothers continued to breastfeed their children. Old women scrubbed their laundry. Fathers commuted to work. The manufacture of heavy war machinery could not wait. If a soldier was tying his shoes, then he finished tying his shoes. If a woman was seated on stone steps, if she was resting, then there was no reason to rush standing up. If the Americans chose to bomb the city, there was little anyone could do to stop them. Even in the event that the outmatched Japanese defenses downed a few bombers, it would likely be a very small number, and this would not prevent the Americans from burning down vast swathes of the city. Anyway, Hiroshima’s luck might hold; so far the bombers had left it alone.

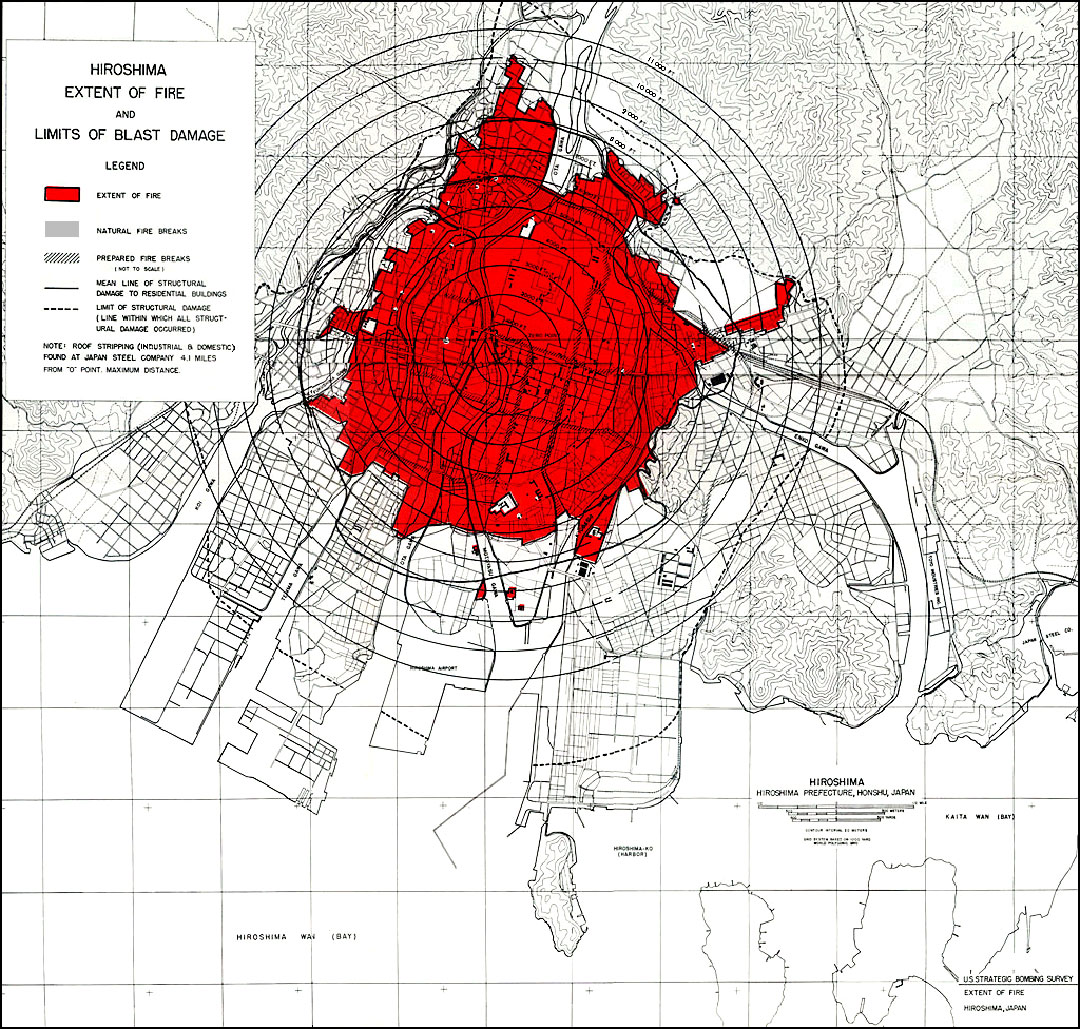

Then Little Boy fell. The force of the explosion instantly leveled buildings and ruptured flesh. The incredible heat vaporized many bodies and melted others’ skin, which hung from them in drips and ribbons. Those who survived had no context for this strange new hell. They did not have a word for what had been done to them. It was not like the firebombings that had terrorized Japan’s major cities since the March 9th and 10th raids on Tokyo. The bodies of the people of Hiroshima were not only burned, but deeply changed, twisted and made strange. Many who were not immediately killed would spend the rest of their lives dying. Some lay down in the streets and waited for the end. Some would have to wait years. Others would live and remember.

From 2009 to 2012, I wrote a novel called Fat Man and Little Boy. It imagines that after we dropped the atom bombs on Japan, those bombs were reincarnated as people: a fat man and a little boy who believed they were brothers. I spent the better part of these three years reading and watching accounts of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I found that we Americans tend to prefer the image of the mushroom cloud to depictions of the bomb’s effects on our victims. Even Dr. Strangelove, arguably the bleakest Western cinematic depiction of nuclear destruction, ends with an orgasmic montage of mushroom cloud imagery, favoring this bloodless synecdoche for nuclear violence over the lived, embodied experiences of the victims. When George W. Bush was campaigning for Americans to support his invasion of Iraq, he did not raise the specter of radiation poisoning or melted skin but the image of a mushroom cloud. Even in our own nightmares, we habitually use that sanitary plume of smoke to obscure our view of the real violence that our bombs did to real people.

Pikadon clears the mushroom cloud. No account of the atomic bombings of Japan has ever touched or unsettled me so deeply as this animated short. It was made by the husband-and-wife team of Renzo and Sayoko Kinoshita, the proprietors (and most of the staff) of a Tokyo-based independent animation studio called Studio Lotus. Though the Kinoshitas were influential in the Japanese and international animation communities (Renzo died on January 15, 1997; Sayoko continues to serve as the director of the International Animation Festival in Hiroshima, which the couple helped to establish in 1985), it can be surprisingly difficult to find reliable information about their films. When I first found Pikadon online, it was erroneously attributed to Osamu Tezuka, the legendary manga artist and animator most famous in the United States for creating Astro Boy; though Tezuka collaborated with Renzo on other projects, he had no role in Pikadon’s production. It’s also unclear whether Pikadon was released in 1978 or 1979.

With so little to go on, it’s difficult to ascertain who saw Pikadon and how they saw it before the film was uploaded to the Internet. At the time of its release, the use of animation to depict such a tragedy was controversial. In a letter to animation historian Karl Cohen, Sayoko Kinoshita reportedly wrote that the people of Hiroshima did not like the idea of Pikadon while it was in production. Yet according to Frederik Schodt — an author and translator who has written extensively about Japanese culture — the short won nominations and prizes at film festivals in London, Moscow, Sydney and Los Angeles. Still, Pikadon doesn’t appear to have ever seen commercial release, and as far as I can tell, the closest it ever came to entering popular culture was in a picture book of stills re-released in 2010 with essays in Japanese and English providing historical context. Today, the short is only available via video-streaming websites, and the quality of each version ranges from poor to atrocious. Distorted audio, ruined colors and large chunks of missing footage are the norm.

The best available version of Pikadon is in the above French documentary on the Kinoshitas. It is a testament to the power of the film that it still resonates so strongly despite its diminishment by accidents of time and technology. In its first half, Pikadon captures a serene city, a home to kind families and good people who take time to enjoy peace and stillness even as an air siren insists that they must not be calm. Its second half describes what Little Boy did to these people, how they suffered and what became of their home.

Pikadon means “flash boom.” It refers to what those witnessing the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki saw and heard: first a blinding light, then a deafening explosion. Translators Yuko Enomoto and Bruce Rutledge explain that, in Japanese, “pikadon” has an onomatopoeic quality, just as “boom” does in English. Also, like its translation (“flash boom”), I’m told “pikadon” has a primal or visceral feel; it does not read as a carefully considered phrase, but a panicked exclamation, the gut response of a person terrified almost beyond the point of speech. It is appropriate then that Pikadon is mostly silent — or rather, that the film is sometimes very loud, but it has no dialog, no human speech.

While it is not difficult to find frank written descriptions of the atomic bombings or shocking photographs of what they did to buildings and people, Pikadon is unique in the way it uses a mixture of naturalistic and surreal gestures to evoke the horrors of Hiroshima. In its brief running time — not quite nine minutes — Pikadon creates an opportunity for viewers to make a powerful, disquieting, empathetic connection with people long silenced by the bomb.

In its early minutes, Pikadon balances a feeling of impending doom with its love for the people of Hiroshima. The short opens with a title card displaying the date of the bombing: August 6, 1945. All we can hear is the oppressive, overbearing ticking away of the seconds. The scenes of domestic happiness and natural beauty (a loving family, laughing children, dewy flowers, a student watching ripples in a pond) serve both as a reminder of what was lost and as a reason to hope, however irrationally, that the bomb will not really fall. It seems absurd that anyone should want to kill such people. For about one minute and 45 seconds, the sound of the clock is drowned out, first by the pleasant summer hum of cicadas and then by the sounds of the city. It seems almost plausible that this moment might last forever.

But then we hear the clock again. We see the bomber. Hiroshima’s citizens are frightened by the sight and by the cry of the air raid siren that follows, but they continue living as they did for just a little while longer — they work, they care for their children, they wash, they tie their shoes.

Pikadon’s latter half is a different beast. Light floods the screen; those it touches are frozen in that moment, then never seen again. Footage of the explosion, either treated to alter its color or possibly rotoscoped, plays for 40 seconds. Initially, it’s easy to recognize the explosion for what it is, but as the smoke continues to unfold across the frame, its shape rapidly becomes less familiar, losing meaning as the viewer is forced to confront it becoming not the familiar (almost friendly) cartoon mushroom cloud but a strange, messy blight, shapeless and impossible to contain.

The victims’ bodies prove similarly impossible to restrain. They overflow, melting rapidly, eyes pouring from their skulls, limbs bursting from their clothes. People scream soundlessly for help. In Pikadon’s climax, the Kinoshitas use cartoon art to suggest what can never be fully spoken. As ruined people fill the screen, Renzo does not attempt to depict their every malady, but draws them as malformed abstractions: figures with unlikely skin colors, unfinished bodies, hastily sketched faces. These horrors cannot be contained by any retelling. They can only be suggested in fragments.

Pikadon ends on a complicated image of hope and resilience. Before the bomb fell, we saw a little boy throw a paper plane. It immediately fell to the ground. Now the camera closes in on the boy’s remains. We fade to what seems to be a vision or a dream. The little boy throws his paper plane again. This time it soars up into the clouds and circles the globe, returning finally to modern Hiroshima, a city full of massive buildings covered in blinking neon signs. Even after the bomb, Hiroshima thrives. Yet there is a sense of lasting loss here: For all the virtues of a metropolis, it is difficult to imagine its citizens enjoying again the sort of serene contemplation that characterizes Pikadon’s depiction of Hiroshima before Little Boy.

Mike Meginnis' debut novel Fat Man and Little Boy won the 2013 Horatio Nelson Fiction Prize. It will publish in October 2014 from Black Balloon Publishing and is available for preorder now.

Author Mike Meginnis has published stories in Best American Short Stories 2012, The Collagist, PANK and many others. He contributes regularly to HTML Giant and Kill Screen, and plays collaborative text adventures at Exits Are. Meginnis earned his MFA at New Mexico State University, where he served as a managing editor of Puerto del Sol for two years. He now lives and works in Iowa City, where he operates Uncanny Valley Press with his wife, Tracy Rae Bowling. He has never seen the ocean.