Max Balkin in Heaven

Walking into Max Balkin’s Harlem studio, I’m greeted by an array of brewing equipment — tubes, pipes, a beaker, something that looks like a Gatorade tank. He pours boiling water into the tank (a “mash tun” used in the process of converting malt starch to sugars for fermentation) and adds a grain to it gradually, filling the room with a smell I’ve only ever associated with oatmeal and brown sugar.

“This is the malt, this is the base for all beer,” he tells me, while mashing. “There are three, four different kinds of malt in here, and you change the malt depending on what you want to brew. These are mostly pale malts, so you get some caramel sweetness from it.”

This is the 12th batch of beer Max has brewed in his Manhattan apartment, which becomes a mini-brewery of sorts every few weeks. When he isn’t brewing at home, he serves beer at Gun Hill Brewing Company in the Bronx and tries to learn as much as he can from the brewers there.

At Max’s apartment, we nurse a few beers — including the deliciously hoppy Tripel Belgian ale from his last batch — and discuss the trials and tribulations of making your own beer, as well as hops’ connection to weed and how New York’s brewing industry is changing.

Max's home brewery

Freddie Moore: What would you compare the process of brewing your own beer to?

Max Balkin: You’re basically making coffee on a very large scale and then fermenting it. The process itself — the idea behind it — is really simple. You’re extracting the sugars from the grain, you’re boiling that [the sparge water] — that’s when you add the hops for flavoring — and then you cool it and put it into a big jug, let it ferment, and you add your yeast. It’s three pretty simple steps. It just takes a long time because you’re dealing with a lot of volume and you’ve got to boil a lot of stuff.

It also sounds like you need to follow instructions carefully.

Yeah, it’s kind of like baking in that sense, although beer is very forgiving. If you screw something up, chances are it’s still going to come out pretty okay.

Have you had any instances where you brewed a whole batch of beer and you realized, oh, there’s something off here?

Well, it depends on what’s wrong with it. I had a beer where — I brewed it last year, it was a hefenweissen, a German wheat beer, and it was disgusting. It came out awful. What had happened was you’re not really supposed to brew that during the summer because it’s too warm. You want the temperature while it’s fermenting to be at around 55 to 65 degrees, and it was probably like 80 degrees here while it was fermenting. So it was way over the top, and it just tasted like garbage. I had to dump the whole thing. This is my 12th batch, and I’ve only ever really had that one go wrong. I’ve had others that were not so good, but they weren’t bad. They were just not what I expected, but they were definitely drinkable.

My next investment is to buy a chest freezer so that I can control the temperature during fermentation. It’s a neverending cycle of new equipment that you can buy. I don’t know how much money I’ve dropped so far, but, you know, it’s adding up. The only thing is once you do one thing, you’re always trying to improve upon your last batch. So if I could control the fermentation temperature, the outcome is going to be a lot better. … It’s just part of trying to one-up my last batch.

What’s your process for buying ingredients? How much does it typically cost you?

For a stronger beer, it’s going to cost more money because you need more ingredients. This is probably going to be a 5 percent, maybe a little bit lower, and it cost me about $30 to $35 [for 48 12-ounce bottles of beer]. That’s including the grains, the yeast and the hops.

What’s your best source been in terms of finding recipes? Do you ever do much in the way of playing with them or adjusting them with each brew?

The first time I saw a homebrew happen was at my brother’s apartment. He and his friend were doing it, and after I watched them do it, I immediately went home and ordered a couple hundred dollars worth of equipment. I just wanted to dive right into it.

But the first beer I brewed on my own was from a recipe kit, which you can buy on various websites. They send you everything you need, they give you the recipe, they tell you how to do it with instructions and everything, so it’s more or less foolproof. That’s a good way to get a handle on the whole process. Shortly after that, I think I did a couple recipe kits and then I started designing my own recipes.

Did you work around ones you had used before according to the flavors you were going for?

Yeah, and what ingredients were available. I would go online and find other people’s recipes and adjust them or tweak them a little bit. There’s actually a really good software that I use now called BeerSmith. It’s basically a recipe program that allows you to create recipes and adjust them. It’s really, really in-depth. It tells you exactly what to expect from your final product. Once I bought this, I started really trying to fine-tune my recipes.

Do you keep a log of the recipes you’ve used before?

Yeah — I mean, this program keeps everything in there, all the ones I’ve designed. ... It tells you all the ingredients, the process — it actually gives you brew steps, like a recipe essentially. And the beer came out pretty well, but then I went back and decided, well, next time I want it a little bit more this or a little bit more that. So I re-did the recipe.

The Beer Judge Certification Program is even built into BeerSmith, so all of their guidelines are in here as well. As you’re plugging in the ingredients, it tells you how strong it’ll be, how bitter it will be, the color and the estimated final strength.

It sort of makes you wonder what people did before this technology was around.

Well they used to figure it out in their heads! The brewmaster at where I now work, he does it all on paper. He’s been brewing professionally for 22 years, well before this stuff came out, so he just does everything in his head. He already knows exactly what’s going to happen.

Is that your goal for the future? To have that sense of exactly what’s going to happen with your brew?

Well, my endgame is to be a professional brewer.

It would be that ideal hobby-turned-profession scenario. The thing you love actually turns into the skill that earns you money.

Exactly, and that’s what happened with that same guy, the brewmaster. He started his own brewery. The craft beer boom that’s been happening over the last four or five years or so, that’s how a lot of it happened. There were just a lot of people who were homebrewers and wanted to go pro, so they got some money and bought a brewery or started a brewery. Without home-brewing, craft beer would not be where it is right now.

Do you know why it boomed all of a sudden?

I don’t know. People’s tastes, I would assume, because up until the mid to late ‘90s you really couldn’t find any beer that wasn’t domestic, light, shitty beer — Budweiser and whatnot. And then Sierra Nevada was one of the first craft breweries. I think it just snowballed, it picked up momentum. People tasted really good beer, and they wanted more of it. They figured out that they could homebrew, and they figured out that there were other places that they could go to try new beer.

More recently, in New York at least, there’s also the Farm Brewery License. Gun Hill Brewery is one of the first craft breweries in New York City to have one. It’s a really huge initiative to increase the revenue of farms in New York State, which is really a good thing [for brewers] because they’re really giving these licenses away. Before, it was really hard to get a brewer’s license; now they’re just sort of passing them out. It’s pretty exciting. It’s exciting for farmers, obviously, and it’s exciting for brewers because now if you want to open a brewery, you can do it pretty easily. You just need to find the people who will produce New York State hops and barley.

Within the next two or three years, the supply for hops and barley sourced from New York State is going to grow exponentially. It’s going to be a lot more than can meet demand. If I had any extra money right now, I would be investing in barley production and hop fields.

Speaking of hops, I was actually going to ask about hops and marijuana because there are some really hoppy beers that just smell like weed.

Yeah, depending on the type of hop that you are using, they usually smell very similar. They basically look the same. They’re both members of the same plant family [Cannabaceae]. They’re very similar in a lot of ways. Don’t smoke hops — you’ll vomit — but you can make beer with weed, and you can make beer that will get you high.

So it’s a totally different thing then? You’re getting high off it, not drunk?

Well you’re getting both because beer will have alcohol in it and it will have reportable THC in it as well. There are brewers that serve commercial beer with marijuana, but they take the THC out of it to make it legal to sell.

Do you know if California is doing anything like this commercially?

Well, in California, the beer culture is very intertwined with the weed culture. Like Lagunitas — you know their “Censored Beer?” It was originally called “The Kronic,” but they were not allowed to call it that legally. So now the label, it says the product, but there’s a big censored bar over it.

And with Dale’s Pale Ale, on the back of every can of Oskar Blues’ beer, there’s a little tiny pipe screen. That’s their homage to smoking weed!

There’s another story behind Dale’s Pale Ale too, isn’t there?

It was a bathtub recipe he did during college! He submitted it into a competition, and he never changed the recipe after that. It’s been a huge success. Oskar Blues was the first craft brewery to can their beer, and they’ve been doing it for a while.

How does canning affect it versus bottling?

Canning is decidedly better for the beer. It keeps it fresher. It keeps it 100 percent protected from light, which is one of the major detrimental factors that can reduce the flavor of your beer. It also keeps it oxygen free. It’s the best way to store your beer other than kegs.

It’s weird because cans sort of get a low-brow, mass-produced stereotype though.

I don’t know why macrobreweries decided to start canning, but it was probably for consistency, it was probably to keep a more consistent product. Actually, the history of the dude behind Budweiser — he was the “Busch” of Anheuser-Busch. He was fascinating. I don’t remember his entire story, but his whole thing was that he wanted his beer to taste the same no matter where you got it in the world. That’s probably how that came into play, with the globalization of a product.

Canning is more expensive, and it’s a harder process to do than bottling, but it’s better for the beer. That’s why a great craft beer, like Heady Topper, is only available in cans. There’s one restaurant in the world that serves it on draft, and that’s it. Other than that, you can only get it in cans.

Speaking of which, what are a few of your favorite beers currently?

It’s very cyclical. My favorites recently ... you know Sixpoint Brewery out in Greenpoint? They have an oatmeal stout. I’ve only ever seen it in one place, but it’s delicious. It’s one of my favorite beers of all time. It’s called Sixpoint Otis.

Hmm … what else? You know Ommegang from upstate? Once or twice a year they put out a brew called Gnomegang. It’s a collaboration they do with a Belgian brewery, and it’s fantastic. Every time I see it, I have to have it.

Freddie Moore is a Brooklyn-based writer. Her full name is Winifred, and her writing has appeared in The Paris Review Daily and The Huffington Post. As a former cheesemonger, she’s a big-time foodie who knows her cheese. Follow her on Twitter: @moorefreddie

(Image credits, from top: Facebook; rest by author)

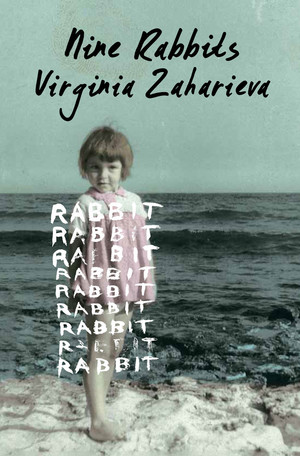

This blog post about cooking (sorta?) is brought to you by Nine Rabbits, the bestselling novel by Virginia Zaharieva now available from Black Balloon Publishing.

About the Book:

A restless writer's fiery enthusiasm for her family's culinary traditions defines her from childhood to passionate adulthood as she strives for a life less ordinary. Lush gardens, nostalgic meals and sensual memories are as charming as the narrator herself.

About the Author:

Virginia Zaharieva was born in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1959. She is a writer, psychotherapist, feminist and mother. Her novel Nine Rabbits is among the most celebrated Bulgarian books to appear over the past two decades and the first of Zaharieva's work available in English.

KEEP READING: More on Food

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©