Even metaphorically speaking, I never followed the old adage “Don’t shit where you eat”. I’ve tried to sleep with people I worked with and drank heavily at the bars I worked at. I even sold drugs from my rented room in a BedStuy duplex, sometimes to other tenants. But when I moved from Brooklyn to Portland, I thought maybe I would try to live a bit more responsibly, that my days of shitting so close to my dinners were over. Then I moved in with a tattoo artist named Manny who composted all our garbage and, on the first official day of spring, shaved himself a mohawk and began digging in the yard. I was about to learn about truly organic, self-sufficient, vegan gardening. This was farming with humanure.

In the first few weeks of living with Manny, I learned that he — like almost anyone under 40 in Portland — subscribed to all sorts of idealistic principles that made living the lazy way I did practically impossible. His diet alone was more discriminant than anything I believed or practiced. He didn’t eat gluten, meat, dairy or refined sugar. If something had been procured from an animal who might have otherwise objected, he didn’t use it. I thought I knew radical eaters having lived in Brooklyn over the past decade, but this was something else. When I asked him about his reasons for limiting his diet and lifestyle, he said, “If I can survive without it, why bother? Actually, you know what? If I can live perfectly healthy and not even suffer without it, why would anyone bother?”

One of Manny’s gardening beds

Manny’s totally animal-friendly garden consisted of five beds in the backyard. Manny filled each bed with compost from a pile consisting of spent coffee grounds, eggshells and every errant scrap of organic food he hadn’t consumed in over a year. He got the more vulnerable seedlings, like certain tomatoes and bell peppers, started in wet paper towels until they sprouted, after which he moved them into little plastic pots of soil. From there, they went into the beds, which were outfitted with the compost and almost ready to go. Having done most of the dirty work, there remained only one deed, perhaps the dirtiest of all.

Manny and I set about how we’d do this part of the equation with the utmost care and sanitation. We figured if we lined our toilet with triple-reinforced plastic bags and dropped our respective deuces into the toilet as usual, we’d be fine. Once the pooping was over, we’d tie the bag up and get it out of the house as quickly as possible with obvious attention to holding our breath and looking away from the shopping bag full of our own shit.

I would like to say that, in that moment, I told myself the same thing I told myself when I was on the other side of the country, amongst junkies in Brooklyn, waiting for a drug dealer to show up: “When in Rome ...” or perhaps “YOLO!” But in truth, I didn’t tell myself anything because I was too busy giggling hysterically. Self sufficiency! Fuck you cows! Or, no, I guess thank you, cows, but no thanks. We got this one.

We emptied the bags into the beds and covered them with soil like a pair of overgrown feral cats. Then we waited. The next stage was almost entirely boring, and I felt what I imagine cannibalistic serial killers must feel after they have horribly murdered and eaten their victims, which is that clean up is lame, regardless of how gruesome the act. The gross parts end up being the most exciting, and once they are over, you’re just waiting for the next thing.

We waited. Time passed. Normal food was consumed. Toilets in our home flushed with a special echo of wasted potential. The sprouts grew into whatever you call plants that are starting to produce the little infant versions of fruit and vegetables (baby fruits?), then that stuff got bigger.

Finally, it was time to harvest. Manny wanted to invite friends over to celebrate the occasion, but I thought this was not something that was meant to be shared amongst those we knew, who thus far had held us in high esteem. “Let’s keep this to ourselves,” I said. “We did the work, we took the shits, let’s just us eat the food.” He reluctantly agreed. We decided to keep the meal simple so as to accentuate the flavors and subtlety of this supremely natural, organic grub.

We had two different kinds of salad: one with kale and pine nuts, one with cucumbers, tomatoes and a few different kinds of squash. There was a sort of medley of root vegetables, like carrots and turnips, but we were pickling most of that stuff as a sort of experiment along with some peppers.

The actual food we made was decent — not particularly amazing, but not bad at all. In the end, I only really learned that true self-sufficiency doesn’t matter all that much to me. Like most things, I end up not being able to stick with it when there’s much easier, though less efficient, ways to live. I’m like anyone: apathetic and wasteful, jaded and lazy. And for all the ideas I’ve had, I’ve flushed a whole lot more shit than I’ve planted.

Cris Lankenau is a writer and musician living in Portland, Oregon. You can find his Soundcloud page here.

(Image credits: All courtesy of author)

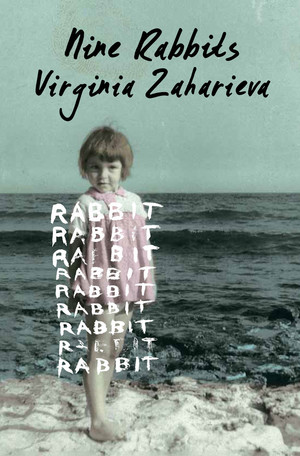

This blog post about gardening is brought to you by Nine Rabbits, the bestselling novel by Virginia Zaharieva now available from Black Balloon Publishing.

About the Book:

A restless writer's fiery enthusiasm for her family's culinary traditions defines her from childhood to passionate adulthood as she strives for a life less ordinary. Lush gardens, nostalgic meals and sensual memories are as charming as the narrator herself.

About the Author:

Virginia Zaharieva was born in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1959. She is a writer, psychotherapist, feminist and mother. Her novel Nine Rabbits is among the most celebrated Bulgarian books to appear over the past two decades and the first of Zaharieva's work available in English.

KEEP READING: More on Food

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©