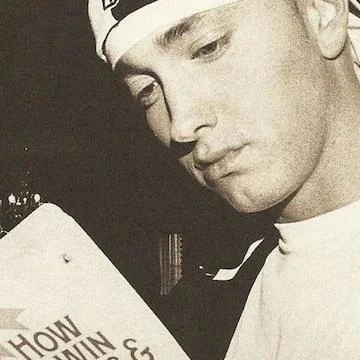

David Foster Wallace (via Doves & Serpents)

David Foster Wallace had a poster of Alanis Morissette on his bedroom wall. She was, he said, his celebrity crush.

"I have the musical taste of a 13-year-old girl," Wallace told a Rolling Stone reporter in 1996. But whatever Wallace told journalists is probably best taken with a little salt. As he told the same interviewer: “I think that there is, in writing, a certain blend of absolute naked sincerity and manipulation.”

While Wallace was inventing Enfield Tennis Academy, the Incandenza family and Eschaton, the 33-year-old was listening to Nevermind, In Utero and Jagged Little Pill. The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here or The Wall may have popped up too; in high school in Illinois, as a stoner "dirtbag" and tennis star, he said he listened to lots of Pink Floyd.

In Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, biographer D. T. Max recounts how Wallace and his college roommate Mark Costello traded tapes by rappers Public Enemy and N.W.A. and co-wrote an exegesis of hip hop called “Signifying Rappers.” But, as Max writes, “Wallace’s passion for rap was theoretical, verbal, abstract. The music never touched him as did the stoner songs of high school or the tripping songs of Amherst.” He was willing to dance with Mary Karr, the poet, memoirist and one love of Wallace’s life, at her 20th high school reunion, but only to the slow songs. While courting another girlfriend, Max writes, Wallace “shared corny pop songs like Ed McCain’s ‘I’ll Be Your Crying Shoulder.”

On the road trip they took together, to the last stop on the Infinite Jest book tour, Wallace and Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky listened to R.E.M.'s album Monster on repeat. Wallace also played a Brian Eno song to show how much it sounded like Bush's "Glycerine," Lipsky reports in the book he published after Wallace's death, Although Of Course in the End You End Up Becoming Yourself.

Following his death, David's sister Amy spoke to a radio interviewer about the music her brother had liked: Pearl Jam, U2, a cover of "Our Lips are Sealed" by Fun Boy Three, the ska band Madness. "He kind of got stuck in the ‘80s," she said. After a pause, she added, "Oh yeah, The Flaming Lips. He loved The Flaming Lips."

Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots by The Flaming Lips (via Listal)

The day I got into college, my father found me up in my room with four friends, candles lit, listening for the sixth time that day to Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, which had just been released. If I'd read Wallace by then, I might have realized what an Enfield moment this was — teenage dudes blissed out to a psychedelic record on the first day of Christmas break. On finishing the last page of Infinite Jest years later, I turned back again to read the first. I'd found a new Yoshimi.

Re-listening to Flaming Lips records like Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots and The Soft Bulletin after reading Infinite Jest, it's easy to see that Wallace and Lips songwriter Wayne Coyne have common sensibilities: the odd mix of humor and sadness, absurdist fantasy and earnest emotion.

Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, like Infinite Jest, is a dystopian story, alternately funny and emotionally raw. "Ego Tripping at the Gates of Hell," the Flaming Lips song, even sounds like something Wallace might have written; ditto to lyrics like, "It's summertime / And I can understand if you still feel sad / Look inside: All you'll see is a self-reflecting inner sadness / Look outside and I know that you will recognize / It's summertime."

More Coyne lyrics, this time from “All We Have is Now”:

As logic stands you couldn’t meet a man

Who’s from the future

But logic broke as he approached he spoke

About the future ...

I noticed that he had a watch and hat

That looked familiar

He was me from a dimension torn free

Of the future

“We’re not going to make it,” he explained how

The end will come - you and me were never meant

To be part of the future -

All we have is now

There again, this endearing existentialism sounds an awful lot like Wallace.

Then there's the zaniness — like a song about falling in love with a robot who has learned human emotion — treated with full earnestness. Sure, “One More Robot” is a song supposedly about robots, not people struggling with affectation and authenticity, but consider the lyrics:

Unit 3000-21 is warming

Makes a humming sound when its circuits

Duplicate emotions and a sense of coldness detaches

As it tries to comfort your sadness …

It’s hard to say what’s real

When you know the way you feel

Is it wrong to think it’s love

When it tries the way it does?

And compare them to this excerpt from “Farther Away,” Jonathan Franzen's essay about Wallace:

How easy and natural love is if you are well! And how gruesomely difficult — what a philosophically daunting contraption of self-interest and self-delusion love appears to be — if you are not! And yet one of the lessons of David’s work (and, for me, of being his friend) is that the difference between well and not well is in more respects a difference of degree than of kind.

You’ve barely finished laughing with a Flaming Lips song or Wallace’s writing when the sadness surprises you by surging back.

A list of Wallace’s top 10 favorite books that he compiled before his death in 2008 includes Tom Clancy, Stephen King and Thomas Harris. On the other hand, in a Salon interview, he listed the sort of influences you might expect if you’ve read his work: Pynchon, Joyce, DeLillo, Kant, Wittgenstein. It’s not untrue that Wallace loved genre fiction and page-turners, but lists of favorites are misleading for an author so broad. He liked X, but also Y; Robert Heinlein and Raymond Carver; Alanis Morissette and The Flaming Lips; everything and more.

Wallace wasn't insincere, but he held different sensibilities to different people at different times and was aware of that. (We all do, he’d say.) It’s that plethora of voices in Wallace's prose that readers love — the cycle of perspectives and moods, the openness to different registers, the ability to connect with cultures high and low. He resonates at different frequencies. And if you listen closely enough, though he never wrote a word about them or their music, you can hear, among those frequencies, The Flaming Lips.

Taylor Beck writes for GQ, Fast Company and other magazines in New York. He was once a dream researcher in Kyoto, a teacher in rural Japan and a neuroscience flunky in labs from Princeton to St. Louis. He agrees with David Foster Wallace that reading is the best way out of a skull-shaped cage, and with both The Flaming Lips and Copernicus that we are floating in space.

KEEP READING: More on Music

![The Rip Van Winkle of Punk [NSFW]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/507dba43c4aabcfd2216a447/1404137063331-A07C54MCRBO7F7AD1CC5/spike10.jpg)

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©