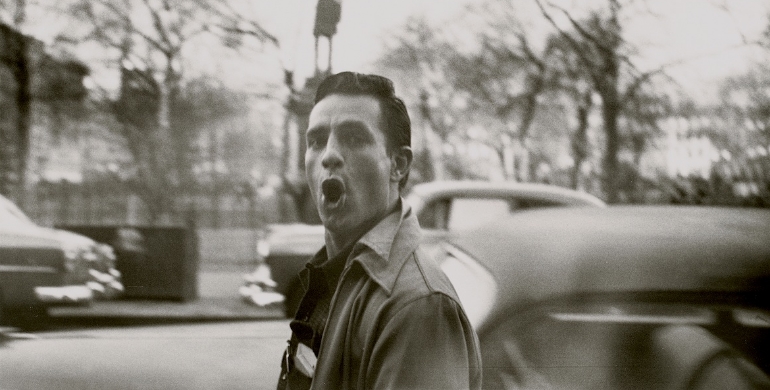

Charles Bukowski (via MJP Blog)

Almost all great writers owe a degree of their distinction to the city that they call home. Saul Bellow’s dense, intellectually forward-thinking prose evokes the fast-paced life of Chicago, and it’s hard to imagine Bret Easton Ellis coming from anywhere other than the San Fernando Valley. Yet this formula can be misleading: F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote so memorably of the rich, pretty things in 1920s New York, was himself from the Midwest, while Jack Kerouac, who espoused a beatnik lifestyle whilst drinking and hitching his way through San Francisco, grew up a devout Catholic in Lowell, Massachusetts. Some writers wholly embrace the regions that form them, while others do their best to forge a new identity despite their hometowns.

Charles Bukowski doesn’t really fall on either side of the spectrum. It’s hard not to argue that Bukowski enforced some of the most tired tropes of Los Angeles culture: that it’s a city of vultures, eager to prey on the young and beautiful; that it’s a cesspool of loose morals and, in spite of its surface diversity, an increasingly narrow culture obsessed with material triumphs. Yet Bukowski, a lecherous, violence-prone cynic for whom simply getting through another crappy day was an almost Herculean battle, remained an outsider all his life.

Bukowski (via Cinematheia)

Throughout his days in scuzzy, crime-infested East Hollywood, Bukowski’s lifelong commitment to truth-telling and an infatuation with the squalor of urban life ensured that he was anything but fake. It comes across in his writing, too; at times, it’s hard not to be put off by his treatment of female characters, but the man’s descriptions of Los Angeles are raw and honest.

Bukowski was born in Andernach, Germany following World War I, the son of an American soldier and the German woman with whom he was having an affair. Young Charles would go on to spend most of his life, however, in Los Angeles, where he penned some of his most well-known works, including Post Office, Ham on Rye, short story collections like Hot Water Music and Hollywood, which eviscerated the sycophants and coattail-riders of the neighborhood and industry.

Post Office (via The Quarterly Conversation)

Ham on Rye (via Dust and Drag)

Hot Water Music (via Second Story Books)

Hollywood (via Amazon)

Throughout this time, Bukowski lived all over Los Angeles, from pre-gentrification Silver Lake to Skid Row, all the way out in San Pedro near the port — and his writing showcases a broad and varied reflection of the city. Post Office, for example, is a decidedly blue collar look at some of L.A.’s seedier neighborhoods, and it’s tempting to read it as autobiography. Like the book’s hero, inveterate wastrel Henry Chinaski, Bukowski was a carrier for the U.S. Postal Service and lived hand-to-mouth in borderline poverty.

Bukowski was an apostle of Los Angeles and a slave to its indulgences. The city undeniably shaped him, his obsessions and his cravings; the Pink Elephant, an East Hollywood liquor store that served as Bukowski’s home away from home, fueled many of his demons. In this way, Bukowski represents both sides of L.A.: enamored with sin, vice and disrepute, yet vital and unique.

Nicholas Laskin is a Los Angeles-based writer who primarily works in screenwriting but also dabbles in prose and journalism. He is the co-creator of the upcoming web series Talents and has worked for the American Film Institute and Sundance. In his spare time, he can be found doing one of the following things: reading, writing, binge-watching movies, making meager efforts at the gym or seeking out exotic and possibly dangerous Thai food.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©