“The Lovers II, 1928” by Rene Magritte (via Rene Magritte)

I first encountered Horacio Quiroga in a high school textbook. It was “The Feather Pillow,” Quiroga’s most anthologized short story in English collections. To be frank, what initially attracted me to it was neither the story nor the author, but the image that the book’s editors included with it. Painted by the French surrealist Rene Magritte, “The Lovers II, 1928” piqued my interest. A strange, haunting painting, it pairs well with Quiroga’s story, which concerns itself with the shocking discovery of parasites living inside ordinary pillows.

Unlike Edgar Allan Poe (his earliest influence) and the French short story writer Guy de Maupassant (whose titular creature in “The Horla” mirrors Quiroga’s monsters in “The Feather Pillow”), Quiroga’s language is stripped of the usual Gothic theatrics. Note how Quiroga builds dread without slipping into “It was a dark and stormy night” cliches:

“Sir!” she called Jordan in a low voice. “There are stains on the pillow that look like blood.”

Jordan approached rapidly and bent over the pillow. Truly, on the case, on both sides of the hollow left by Alicia's head, were two small dark spots.

“They look like punctures,” the servant murmured after a moment of motionless observation. … The servant raised the pillow but immediately dropped it and stood staring at it, livid and trembling. Without knowing why, Jordan felt the hair rise on the back of his neck.

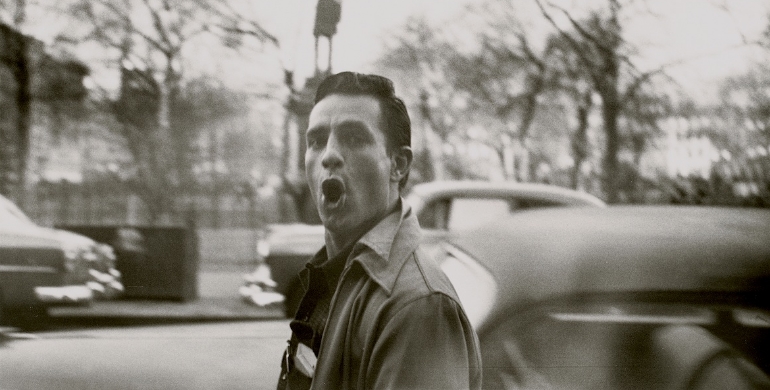

Horacio Quiroga, 1897 (via Wikimedia Commons)

In his early life, Quiroga, the sixth son of a notable middle-class family, would have been more likely to over-dramatize the final reveal of “The Feather Pillow.” Like many with the so-called “artistic temperament” before him, the author seems to have been driven by an impulsive need to write, as well as an unrequited love. After completing school in Montevideo, Quiroga not only dabbled in the various artistic movements at the turn of the century (decadence, symbolism, etc.), but he also developed a passion for Mary Esther Jurkovski, a Jewish woman who remained unattainable because her parents disagreed with her marrying a gentile. While this rejection creatively fueled two of the writer’s most important works (the dramatic play The Slaughtered and the short tale “A Season of Love”), it signaled much darker things to come.

In his work, Quiroga shows a morbid obsession with death and violence (see: “The Decapitated Chicken”), and a large part of this undoubtedly stems from his own life. The opening salvo came before he had even completed his first year of life: In 1879, his father, an official at the Argentine Consulate, was killed in a hunting accident. Years later, after Quiroga had already started publishing his own magazine called Revista de Salto, his step-father committed suicide by shooting himself; the author was the one who found the body. With his inheritance, Quiroga took himself to Paris for a few months before realizing that the Left Bank lifestyle did not suit him. Upon returning to Uruguay, his productive period began in earnest, but in 1902, while cleaning a gun, Quiroga accidentally killed his friend Federico Ferrando. Although eventually exonerated of the crime, the writer soon moved to Buenos Aires, in large part to escape the memory of his friend’s death.

While in Argentina, Quiroga fell in love with the wild jungles of the country’s northern reaches, and after partaking in an expedition to Misiones with the poet Leopoldo Lugones, the author eventually settled and became the owner of a cotton plantation. Quiroga’s bucolic happiness was short-lived, however, and the jungle soon consumed his life. The first victim was Ana Maria Ciries, his first wife: Unable to cope with the harsh environment, she committed suicide by swallowing cyanide. The two children, one girl and one boy, that the married couple had together would also commit suicide years later.

After a decade in the jungle, Quiroga, who, besides his broken heart, had his own fragile health to worry about, moved back to Buenos Aires. He began teaching again and once more he married. His second wife, Maria Elena Bravo, was his daughter’s friend and some 30 years his junior. She too would tire of jungle life, and the pair eventually separated.

On February 19, 1937, Quiroga, at age 58, took his own life by swallowing the very same cyanide that he had been using to treat his various mental ailments for years. The fatalism that had always been such a force in his work finally reached its logical limit, but not before the author had already reached immortality in South America. Comparable to both Poe and Jack London, whose tales about barren wastelands of snow and ice are like Quiroga’s savage stories about man’s futile quest to try and tame the wilderness, Quiroga is widely considered one of the earliest practitioners of great South American short story writing. As such, he can be listed as an influence on talents like Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar. This lasting relevance may well have been Quiroga’s goal, for besides his fantastically dark tales, he also left behind a decalogue of wisdom for all short story writers.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Burlington, Vermont. He prefers “Ben” or “Benzo,” and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Crime Magazine, The Crime Factory, Seven Days and Ravenous Monster. He used to teach English at the University of Vermont, but now just drinks beer and runs his own blog called The Trebuchet.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK AND PINTEREST.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©