Letter from Denise Levertov (via author)

Denise Levertov teaches an aspiring poet that it’s more important to know how to live than to know how to write.

“That is ‘devoting yourself fully to the art of poetry,’ not becoming unemployed and making yourself sit in front of a blank page every day, God forbid!”

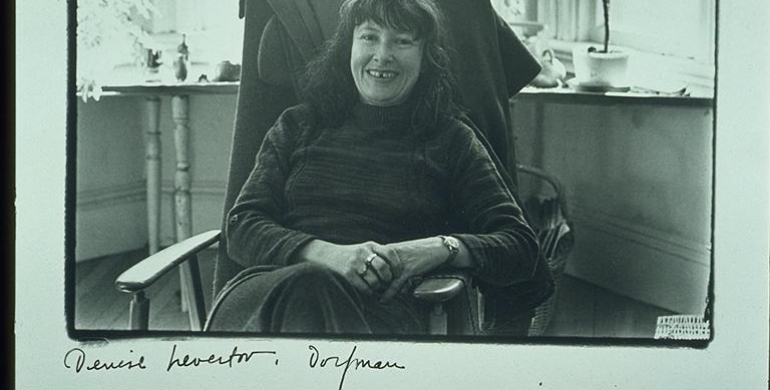

So began my correspondence with my adopted mentor, the poet Denise Levertov. It was 1994, and I was a 22-year-old college graduate just embarking on a career I already detested. I had graduated with a major in accounting and a minor in philosophy, and had accepted a position with an international accounting and auditing firm in November of 1993, the fall of my senior year. But by the time I graduated, the poetry bug had bitten me hard. I wanted to leave my 60-plus-hour-a-week job of flipping through invoices, ticking and flicking, making fastidious adjustments to financial statements of companies I really didn’t give a damn about. There was very little time or energy left over for writing, and writing had become a passion.

My correspondence with Levertov was all too brief. We only exchanged five letters in three years. In December of 1997, I received a typed form letter from her assistant explaining that the poet was “abruptly giving up the habit of a lifetime” and ceasing to respond to all the personal correspondence that by that time had become an “impossible burden” to her. I was disappointed, but at the bottom of the letter Levertov had handwritten, “However, I’d like to hear of your development from time to time — if you can stand not getting a response!” The letter was dated December 8, 1997, just 12 days before she died of lymphoma. My disappointment turned to sadness and then to gratitude when my father showed me a newspaper clipping of her obituary.

Denise Levertov (via Wikimedia Commons)

Denise Levertov was born in England in 1923 and emigrated to America in 1948. From as early as the age of eight, she claimed to know she would be an artist and later consciously aspired to be a “poet in the world,” whose mission was to “awaken sleepers.” In addition to a prodigious lifetime oeuvre, she was politically and socially active her entire life. She and her husband were so intensely involved in the peace movement of the 1960s that they were frequently arrested for protesting, attracting the notice of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Later in life, Levertov worked to combat the horror of the imminent nuclear apocalypse precipitated by the Cold War, while at the same time continuing to give voice to the socially and politically oppressed through her poetry and prose. Her dedication to her craft earned her many accolades, including the Shelley Memorial Award, the Lannan Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Despite how imposing a personality Levertov seemed, I felt that if I wrote to her, she would respond. There was just something about the tone of her writing that indicated she would be open to a conversation. My initial letter was typical of an idealistic, romantic college student whose spirit hadn’t yet been squashed by the real world. I wrote things like “I’ve started upon a whole new inner life” and “I feel both ecstatic and frightened that poetry has drawn me into itself.” Now, in the unforgiving hindsight of 20 years, the letter looks silly. But thank God for it, because both her correspondence and her books gave me what a liberal arts education was supposed to: a means for living in the world, to have life and to have it abundantly.

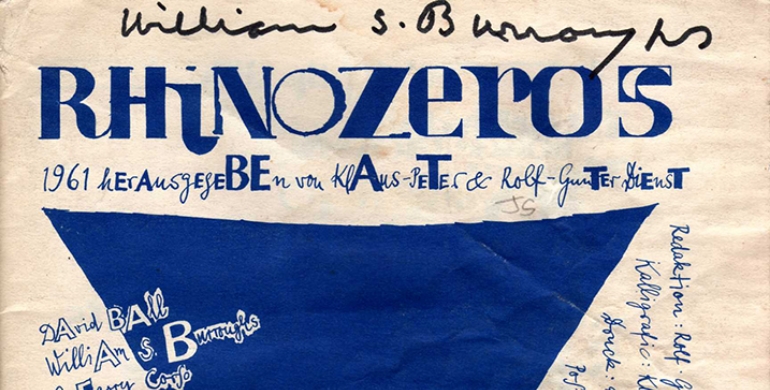

The Double Image, Levertov’s first book of poetry (via Antiqbook)

“The important thing is to keep yourself receptive to the muse, to language & impressions, so that when your time is free to write you are ready to do so — or if not to write (because there’s no virtue in simply writing a lot) then to read, look at nature, record your dreams (not to make poems out of them but because the habit of recalling them — which can be developed — & the act of recording them seems to function as a stimulating experience for the creative imagination.)” That is what she meant by “devoting oneself to the art of poetry.” My naive view of the writer was of someone who sat at his desk all day diligently writing away, waiting for the reticent, fickle muses to come to him and whisper lines of genius into his ear. Needless to say, those muses weren’t particularly forthcoming, hence my frustration. And even though Levertov commented favorably on some poems I had sent her, saying she really liked them and that they were “very, very promising,” I didn’t learn how to write poetry from her. Instead, I learned that it’s one’s attitude toward life and existence itself that is most important.

Being “receptive to the muse” didn’t mean being passive. I was never one to sit back and let things happen. I played competitive soccer my entire life, and my role as center-forward was literally to “make things happen,” which meant to either score goals or set other people up to score. But that sort of self-starting mentality was only geared toward things like sports and a job, maybe even finding a spouse (because that’s what college graduates are supposed to do). I interpreted Levertov’s imperative about the muse to be something more like “make your own luck.” In other words: Do things, live your life, but live it mindfully. Be aware of why you’re doing what you’re doing.

Growing up, I wasn’t really much of a reader. I always loathed book assignments from school. In fact, I didn’t become seriously interested in reading until college. (Maybe that’s because I finally had the time to read what interested me, instead of what was shoved down my throat.) But reading, for me, wasn’t just a form of entertainment; it had become a source of knowledge about the world, the best teacher one could have. Reading, whether fiction or nonfiction, opened me up to other perspectives on life, on different values of life, on ways of making a life. Levertov was telling me, like Goethe had said, “One must be something in order to do something.” Reading the thoughts, beliefs and opinions of others who came from myriad cultures and eras showed me the possibilities of life, of ways of being. But it was Levertov who taught me how to assimilate it all.

Levertov (via The Nation)

Levertov’s approach to poetry was her approach to experience itself; for her, there were no boundaries between art and life. In particular, it was her process of writing what she called “organic poetry” that affected me most. In my first letter to her, I quoted what Rainer Maria Rilke had said about Auguste Rodin: “I must learn from him, not how to make things, but how to compose myself deeply in order to make them.” I knew Levertov had adopted Rilke as her own mentor early in her career, and I had learned of Rilke only through reading Levertov. But what I didn’t realize at the time is that, even though I wanted to compose myself to write poems, I was learning to compose myself to live life. Becoming a CPA, finding a spouse and starting a family — that’s what I thought I was supposed to do. But Rilke and Levertov appealed to me because both had that passionate reverence for life, including their own, and had established their own way of being with fierce independence.

In the spirit of Rilke, Levertov’s organic poetry involved encountering an experience that is “felt by the poet intensely enough to demand of him their equivalence in words: he is brought to speech,” as she wrote in her essay “Some Notes on Organic Form.” So the poet suddenly finds himself moved to write a poem, an impulse that emerges from his reaction to the experience itself. “The beginning of the fulfillment of this demand is to contemplate, to meditate; words which connote a state in which the heat of feeling warms the intellect.” The heat of feeling warming the intellect — it characterizes that synthesis of reason and emotion that is the hallmark of being fully alive. Levertov continues: “During the writing of the poem the various elements of the poet's being are in communion with each other, and heightened. Ear and eye, intellect and passion, interrelate more subtly than at other times.”

In addition to my passion for poetry, the philosophy bug had bitten me just as hard. I loved exploring ideas and being exposed to new ones. But when, a few years after college, philosophy led me to an interest in science, a conflict arose: Intellect and passion began to clash, to the point where “sometimes all night they raise/antiphonal laments,” as Levertov wrote in her poem “Broken Pact.” The cerebral nature of both philosophy and science seemed at odds with “the kind of dreamy state of mind that precedes the emergence of a poem,” as Levertov put it in her second letter to me. Both philosophy and science demanded clear thinking and conceptual rigor; they seemed to leave no room for the mysterious ambiguity that is the essence of the best poetry.

Letter from Levertov (via author)

After a few years of tolerating this existential tension, the answer finally came to me, as if the muses themselves had whispered it into my ear: Philosophy, science and poetry didn’t have to be at odds. That was just the result of always seeing the matter from only one perspective — a defect of vision. Looked at from a different angle, a sort of Archimedean point, they appeared as three heads of the same animal, the same chimera. Philosophy, science and poetry all teach us to look at the world again, but each from its own unique aspect: Philosophy interrogates experience, science verifies it, and poetry translates it into something relatable and relevant to life. I found that this chimera breathed fire into my life.

Instead of practicing one kind of art, like poetry, Levertov taught me to be the artist of my own life. In her image of the poet, I found the proof-of-principle for the type of human being who is poised to flourish: an amalgam that incorporates the reasoning power of the philosopher, the unrelenting empiricism of the scientist and the passion of the poet. In her poem “The Artist,” which is her own translation of ancient Toltec verse, I think Levertov sums it up best:

The artist: disciple, abundant, multiple, restless.

The true artist: capable, practicing, skillful;

maintains dialogue with his heart, meets things with his mind.

Steve Neumann is a writer, teacher and philosophile. He used to blog at Rationally Speaking, and you can read his sporadic random tweets at @JunoWalker.

KEEP READING: More on Poetry

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK AND PINTEREST.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©