Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century, brilliantly translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia, is out from FSG this week. In it, a translator and all-around dandy finds himself romancing a beautiful (and already engaged) woman in the "moving city" of Wandernburg, Germany. All the while, he attends salons to debate about art, philosophy, and other questions of the nineteenth century, and wonders how to escape from the ever-shifting locale.

It occured to me that Wandernburg is the latest in a long lineage of uncharted territories, so I've put together a brief history—from Laputa to Lost.

Laputa, from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

"The reader can hardly conceive my astonishment, to behold an island in the air, inhabited by men, who were able (as it should seem) to raise or sink, or put it into progressive motion, as they pleased...it advanced nearer, and I could see the sides of it encompassed with several gradations of galleries, and stairs, at certain intervals, to descend from one to the other. In the lowest gallery, I beheld some people fishing with long angling rods, and others looking on."

In the third book of Gulliver's Travels, Swift satirizes the stormy relationship between England and Ireland as a large landmass and an airborne island. The latter, which also satirizes the Royal Society, boasts such eccentricities as "a shoulder of mutton cut into an equilateral triangle" and workers "softening marble, for pillows and pin-cushions."

Lincoln Island, from Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island

"The balloon, which the wind still drove towards the southwest, had since daybreak gone a considerable distance, which might be reckoned by hundreds of miles, and a tolerably high land had, in fact, appeared in that direction...They were ignorant of what it was, whether an island or a continent, for they did not know to what part of the world the hurricane had driven them. But they must reach this land, whether inhabited or desolate, whether hospitable or not."

After a disastrous balloon flight, a group of explorers lands on a deserted island somewhere in the South Pacific, and—in line with Jules Verne's boundless optimism—makes buildings out of bricks and even constructs an electric telegraph. However, the island abounds with mysteries (such as a pig with a bullet in it) and the group must figure out where the other humans are, if there are any at all.

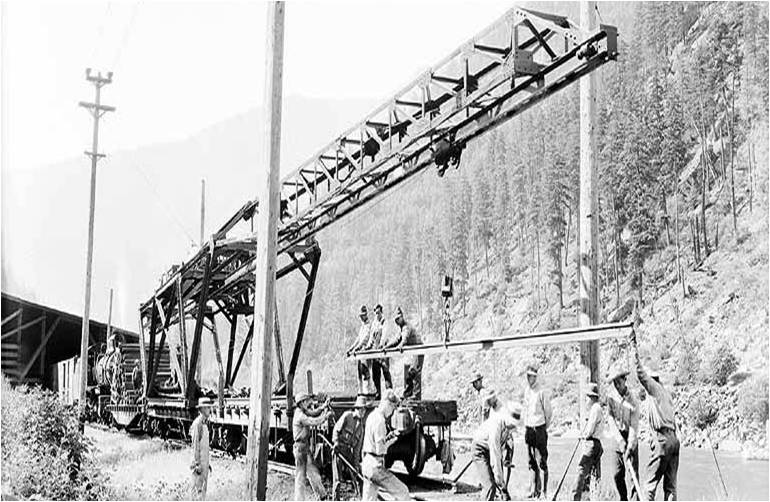

The city Earth, from Christopher Priest’s Inverted World

"[I]t was clear that the rest of the tracks led along a downhill gradient. In due course the final pulley was removed, and all five cables were once again taut. There was a short wait until, at a signal from the Traction man at the stays, the slow progress of the city continued…down the slope towards us. Contrary to what I had imagined, the city did not run smoothly of its own accord on the advantageous gradient. By the evidence of what I saw the cables were still taut; the city was still having to pull itself."

"Earth" in this science-fiction novel refers not to a planet but to a city that moves on tracks at a controlled rate toward an unknown destination. Hundreds of guildsmen must lay tracks ahead of the gigantic structure, and remove the tracks that have already been crossed. In this strange universe, distance literally becomes time—"I had reached the age of six hundred and fifty miles" is the first line—and the ramifications of this city's perpetual movement into the future become increasingly bizarre.

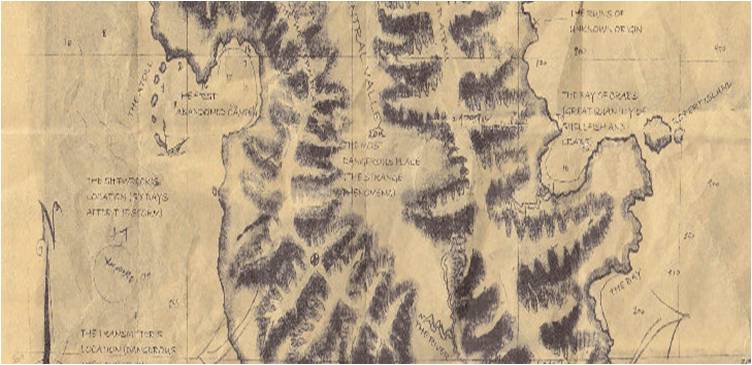

The Island, from Lost

"I've looked into the eye of this island, and what I saw was beautiful." —Locke

When an airplane going from Sydney to Los Angeles crashes on an island in the South Pacific, survival is the first aim of the marooned travelers. But this TV show, which owes an obvious debt to Jules Verne's earlier island, slowly reveals bizarre phenomena—Arctic polar bears, a metal hatch in the jungle's ground—and suggests a very a disturbing reality. The show itself becomes increasingly disorienting, switching from flashbacks and flash-forwards to flash-sideways storylines as it becomes clear that the island can move in time as well as space.

Wandernburg, from Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century

"Wandernburg: moving city, sit. approx. between ancient states of Saxony and Prussia. Cap. of ancient principality of same name...Despite accounts of chroniclers and travellers, precise loc. unknown."

In comparison to these other fantastical inventions, Andrés Neuman’s uncharted city seems positively pedestrian. Although storefronts and streets switch positions overnight, the city as a whole remains relatively moored on land: Hans, the eponymous traveler, is able to send mail to and from various cities in Europe. The focus is less on an isolated space in the world than on an isolated space in the philosophy and intellectual discourse of the nineteenth century. As Hans sits between two countries, so he translates between many languages and the novel itself melds the details of nineteenth-century doorstops with twenty-first-century novelistic techniques. The result is an enthralling epic of a man who bridges gaps of all sorts while looking, always, toward the future.

Image credits: Gulliver beholding Laputa, wikipedia.org; Laputa map, books.google.com; Mysterious Island map, verne.garmtdevries.nl; Great Northern Railway track-laying image, lib.washington.edu; Lost island map, lostified.com; Andrés Neuman photo, nutopia2sergiofalcone.blogspot.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©