If Marilyn Monroe had won an Oscar, the alternate history would have turned out very, very bad for her.

Though not as bad as the vampire scare going around in New England -- and no, these vampires do not sparkle.

Perhaps we're just going to have to meet the real life version of Dracula, and who knows? He could be perfectly charming.

But if you're looking to treat a recent vampire bite, don't trust all the medical advice you find on the interwebs.

But if you're going to turn to books, make sure you know the true origins of any used ones you may happen to come across.

That alone could be a strong case for shaping your brain to be only accustomed to ebooks.

But then again, where will all your crazy marginalia go?

I just dug up my copy of The Great Gatsby, full of my highlighting and marginalia from junior year. I can’t think of a friend who didn’t read it for American Lit in high school, and I’ve only met one person who didn't love its clarity and beauty. I looked at the dedication: “Once again to Zelda.” But the epigraph took me by surprise.

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

—Thomas Parke D’Invilliers

Plenty of books have interesting epigraphs, as Kayla recently pointed out, but I couldn’t believe I had missed this one completely. The poem’s inclusion does make sense, I suppose: the whole book is about self-interested characters trying to charm each other. And there’s a visible shift across the novel from Gatsby’s aloofness, with his showy library (“Knew when to stop too—didn’t cut the pages,” a guest at one of his parties declares), all the way to his final, embarrassingly honest determination to “fix everything the way it was” in order to woo Daisy once more. So the D’Invilliers quotation is a fitting epigraph—another green light leading Gatsby on.

But then I decided to look up Thomas Parke D’Invilliers, figuring he was a nineteenth-century author or a British dignitary. I was wrong. D’Invilliers is a pseudonym for Fitzgerald himself. I was struck by this subtle trick. A pseudonymous epigraph per se isn't all that dishonest, but F. Scott could just as easily have left it unsigned. The same name had surfaced in This Side of Paradise, actually: in that case, D’Invilliers was a stand-in for F. Scott's friend, John Peale Bishop, and in the novel he was an aspiring poet. In real life, as is implied in The Great Gatsby's placing his pseudonym next to several lines of verse, he became an accomplished poet.

But the line's been blurred here: is the Thomas Parke D'Invilliers of the epigraph supposed to refer to John Peale Bishop or Fitzgerald himself? If the author had chosen to call his masterwork Gold-Hatted Gatsby or The High-Bouncing Lover, this question might have been an even more significant one. As it is, it reads like a fumbling attempt on the author's part to erase his presence in the book.

Nick says of himself, “I am one of the few honest people I have ever known.” I didn't always buy that Nick was a fully reliable narrator, given the way he often withheld information from me. So I wonder: if Fitzgerald has been playing with truth from that prefatory page of the book, what else has remained buried under his words, undermining or contradicting the seemingly straight trajectory of his story? Few interpretations of The Great Gatsby have succeeded in aligning F. Scott Fitzgerald with any of the characters within, so why does a trace of him linger here? And if Nick is a liar by virtue of his author's manipulations, then how much has he, as a narrator, been hiding from us about the American Dream?

Some folks make New Years resolutions to drink less and exercise more. This year, I’ve resolved to write better marginalia in the books I read.

In the December 30 issue of the New York Times Magazine, Sam Anderson offers a sampling of his marginalia from some of the books he read in 2011. I admire Anderson for this—it’s like peeking inside another’s intellect and imagination. And his article inspired me to take a closer look at what I write (or don’t write) in the books I read.

I am currently reading Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Which means Dostoevsky’s text is being slowly invaded by my own jottings. I underline, I circle, I draw arrows to connect specific words and phrases, I use exclamation marks to highlight passages I like and large Xs to cross out phrases or plot developments I find obnoxious. And like Anderson, I’m a chronic margin scribbler.

Sometimes my comments are of the ordinary roadmap variety (page 31: “Note importance of physiognomies in D’s descriptions”). Other times, they might point out parallels with other characters/works (page 227: “Note similarities to Raskolnikov’s wandering in C&P) or try to draw out the philosophical depths of Dostoevsky’s story (page 226: “pre-epileptic epiphanic illumination --> higher existence --> fleeting --> sublime moments of infinite clarity and understanding accompanied by suffering”). These notes aren’t intended for some greater end or project (although, come to think of it, it would be interesting to trace the meaning, use, and development of human “strain” throughout Dostoevsky’s novels); they simply represent my brief thoughts and reflections. They help keep me engaged while I read.

Unfortunately, however, I’m a hyper-self-conscious marginalia writer. I dwell too much over the right words, worry too much about trying to express an exact thought. Perhaps I’m also worried about what others might think if they read my scribblings. What if, after I died, a friend came across my marked-up copy of The Idiot? “Why the hell did he write that?" this friend would say. "That wasn’t what Dostoevsky was going for at all! I didn’t know Todd was such a simpleton.” But marginalia ought not be an art of perfection. It should be an informal stream-of-consciousness dialogue with the text. As Rachel recently blogged, marginalia makes reading more participatory and performative.

So as I wrap up The Idiot and begin re-reading The Brothers Karamazov, I’m resolved to become a less self-conscious and more expressive scrawler. Here’s to a 2012 filled with better marginalia.

Photo: Author

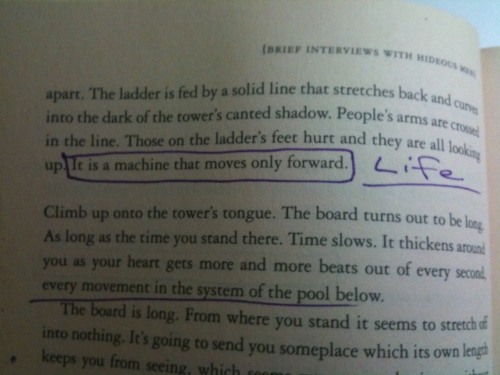

The inner blogosphere of Black Balloon has been abuzz with fake authorial gushiness versus real teen gushiness versus the gush-worthiness of David Foster Wallace faking out teens for real. And this past week, when a package of my old books arrived from my mom, complete with my own teen copy of Wallace's Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, all three confluenced in a cosmic and darkly underscored conclusion.

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©