Writing a diatribe on my doubts and fears of reading Haruki Murakami's1Q84 in English must've been cathartic, because I read the whole damn thing over the New Year's holiday. 925 pages in seven days. Estimating it took me over 14 months to read 1,650 pages of Japanese text, the time practically flew.

Overall, it's quite similar to Murakami's original, though I find the lack of humor magnified in English. I'm pinning this on the omniscient third-person POV, a departure from his well honed first-person narration. Not to say it reads blandly: both translators, Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel, have some fun. Like this naughty gem from Book 1 Chapter 22:

Tengo saw admiration in the eyes of several of his female students, and he realized that he was seducing these seventeen- or eighteen-year-olds through mathematics. His eloquence was a kind of intellectual foreplay. Mathematical functions stroked their backs, theorems sent warm breath into their ears. Since meeting Fuka-Eri, however, Tengo no longer felt sexual interest in such girls, nor did he have any urge to smell their pajamas.

Needless to say, I immediately referred to my own translation:

Tengo looked around the classroom, at the 17- and 18-year-old girls staring at him with awe and respect. He realized he could seduce them by channeling mathematics. His speech was a kind of intellectual foreplay. The functions were a stroke on the back, the theorems warm breath in their ears. But when he met Fukaeri, he lost all sexual interest in these girls. He didn't care to think how they smelled in pajamas.

Here's a gem for you language buffs: 知的な前戯 (“intellectual foreplay”). But I gotta give it to Rubin, hooking in action verbs (“functions stroked”, “theorems sent”) that I glossed over. And that last sentence...no comment.

Rubin and Gabriel split translation duties on Murakami's short-story collection Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman. But, as Gabriel tells The Atlantic,1Q84 is their first collaborative effort on a single novel. Which might explain a few funny discrepancies.

Like the name of Tengo's favorite bar. Murakami's characters internalize their thoughts (even in third-person), and drink whilst thinking. When they're not pouring drams into bedside tumblers, they're out at some bar. In 1Q84, Tengo frequents this one joint near a Kinokuniya (paperbacks at the bar, something I'm emulating in 2012) no less than three times. Murakami calls it 「麦頭」(supplied with tiny furigana adjacent to identify its unique pronunciation), which I translated as “Wheat-Head”. If we're getting nitty-gritty, the first character means “wheat” and is used on beer labels, and the latter “head,” so it could signify the frothy foam atop a draft. Rubin calls it “Barleyhead.” Fine, I'll bite.

In Book Three (Gabriel's translation), this becomes “Mugiatama” (the phonetic translation of those characters), which Gabriel derives into “Ears of Wheat”! I checked the Japanese text and my translation and, yeah, same joint. Tengo's even quaffing the same draft (Carlsberg). Next time he visits, midway through Book Three, Gabriel leaves it as “Mugiatama.”

Finally, that whole “cat town” vs. “town of cats” drama that set me off againstreading 1Q84 in English. Rubin's translation flows predictably enough, like this exchange:

“Did you go to a town of cats,” Fuka-Eri asked Tengo, as if pressing him to reveal a truth.

“Me?!”

“You went to your town of cats. Then came back on a train.”

My own translation practically mirrored this:

"you went to cat town" she said to Tengo as if challenging him.

"I did??"

"you went to your cat town. then you took the train back home"

The original Japanese is 「咎めるように言った」; I called it “said as if challenging” and think Rubin's poetic nudge is a tad excessive. Yet several chapters later, Rubin translates:

“You'll be leaving tomorrow,” Fuka-Eri asked.

Tengo nodded. “Tomorrow morning I have to take the train and go to the cat town again.”

“You're going to the cat town,” Fuka-Eri asked without expression.

“You will be waiting here,” Tengo asked. Living with Fuka-Eri, he had become used to asking questions without question marks.

Imagine my surprise! I feel this reads so much more naturally, calling this far-flung location “cat town.” My translation:

“you're going tomorrow” Fukaeri inquired, looking at him.

Tengo nodded. “I'll take a train tomorrow morning. I have to go back to cat town once again.”

“you're gonna go to cat town” Fukaeri replied, expressionlessly.

“You'll wait here,” asked Tengo. Living with Fukaeri, he'd picked up the habit of leaving the question-marks off his questions.

And several dozen pages later, in Book Three, Gabriel dispenses with “town of cats” mentions altogether, utilizing only “cat town” in Tengo's thoughts and in a letter from Fuka-Eri to him. Best I can do for a response is 「当たり前」, which in slangified English might go “obvs.”

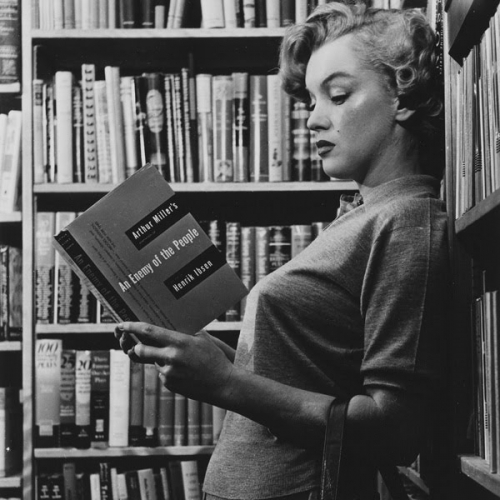

Photo: Mr. Fee

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©