Looking for book cover design pointers from publishing house art directors and graphic designers.

Read MoreLooking for book cover design pointers from publishing house art directors and graphic designers.

Read MoreBefore the publication of his dirty letters, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man revealed Joyce to be quite the kink.

Read MoreNew York, Wichita, Los Angeles — celebrate James Joyce’s Ulysses regardless of where you are.

Read MoreIn which people get real upset over novelists and poets acknowledging the existence of sex and race.

Read MoreOld books! They smell so great! And they’re amazing aide mémoires! My old copy of Ulysses is not so easily coaxed into Wordle manipulation, but it’s got sand from Costa Rican beaches in the splitting glue of its spine, buttery fingerprints on its pages from being read while I ate croissants, and lots of embarrassing underlining, circling, and marginal “insights.”

When you read other people’s old books, you get a similar window into their habits and states of mind. Another example from my shelves: an edition of Beckett’s short prose contained a handwritten note from one stranger to another. I know nothing about them—well, not nothing: one wrote with an exceptional hand and could doodle well. The other was named Tom.

But marginalia’s serendipitous discoveries are made possible only because modern books, codices, are more than merely the information they contain; they are also objects. With eBooks, objecthood becomes problematic. Insofar as they “exist” at all, eBooks are hardly objects. They’re an arrangement of bits on a storage device, hardly dissociable from the device the presents it. And, as we now know, eBooks can be taken from you without someone breaking into your apartment. Notes and highlightings you make on your device aren't really yours to keep, either.

None of this is new anymore. Neither is there much to be done about it, on the broad scale: eReaders and eBooks are here to stay. And the medium is not even a bad one, in and of itself. If we could resolve the privacy issues (when pigs fly), or deal justly with the monetization of your “private” habits (pigs don’t absolutely have to fly for that one, though it is unlikely), some of the data produced could be interesting to future historians studying the tastes of eReader users. Hint: as of today, Kindle-types really liked these sentences, and you can bet that Amazon is keeping records on it all.

But whither the trade in used books as the dominance of the codex withers? The pass-along book trade has never been popular with publishers. It has been seen as a loss of profits, quantified in a way much like the ridiculous amounts estimated to be lost on account of music piracy. (Protip accountant dudes: if consumers don’t have the money, in aggregate, to complete sales “lost” to piracy, those sales weren’t gonna happen in the first place!) So don’t expect a pass-along feature to be built into eBooks any time soon. Which means used bookstores will have to come up with a way to save themselves.

Perhaps they are doomed to employ twee, quirky efforts like Record Store Day. Perhaps we’ll see a Codex Day in the future, when small-run, high-value editions are acquired by ostentatiously self-fashioning consumers.

Perhaps (we might hope) said consumeristas will even leave sticky fingerprints all over their new objects.

Image: flickr user andy54321

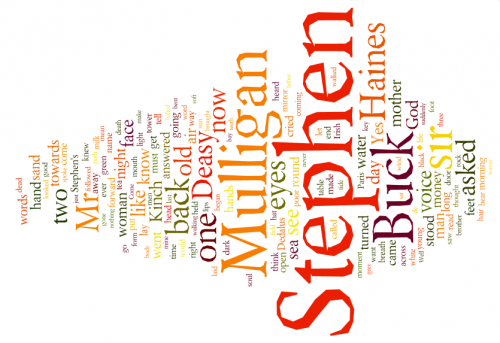

Now that James Joyce's literary corpus is finally in the public doman, I've decided to appropriate it in a singularly 21st-century manner: by readingUlysses chapter by chapter in Wordle, which creates cloud-like infographics based on how often individual words recur in a given text. Visual concordances, more or less.

Each chapter of Ulysses is remarkably different—scholars have noted that chapter breaks serve to shift from one style to another, rather than from one pivotal moment to the next—so I loaded each one into Wordle, let it remove the most common and pedestrian words, and screen-grabbed the results. Here are a few stray observations on the first three chapters, in which Stephen Daedalus's world is fleshed out before Leopold Bloom's arrival.

Chapter 1: Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus (nicknamed Kinch) is talking to his roommate Buck Mulligan in the Martello tower they're both sharing. "God" is mentioned just as often as "mother." The sea and water crop up plenty; the tower is out by the shore, after all. "Mirror" is another popular one, starting with the first line: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." But it's surprisingly renamed in one of Stephen's most famous aphorisms: "It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked looking-glass of a servant."

Chapter 2: Nestor

I've rearranged the words here to keep "Stephen" separate from everything else, since this chapter focuses on Stephen's job teaching, as well as his uncomfortable relationship with the elder Mr. Deasy. There is a great deal of authority and deference in the classroom and in the office: "yes," "sir," and the verbal conjugations of asking and knowing and crying and answering. The word "history" is hidden but memorable here, just as important as books and, ironically, even more recurrent than God: "For them too history was a tale like any other too often heard"; "All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God"; (best of all) "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Chapter 3: Proteus

Stephen's name is all but swallowed up in this chapter, which ditches its protagonist for the "ineluctable modality of the visible." Instead of names, there are his eyes and the sand, everything to see beneath his feet and behind his back. Of all the German words, "nebeneinander" (n:coexistence; adj: in parallel) is the only one frequent enough to appear here. "God" is again recurrent, but not nearly as much as "Paris" or "woman." Everything here boils down to immediate perception and thought, from the concrete elements of the sea and the shore to the clearly abstract mental verbalizations of that which is ineluctable.

I've already read Ulysses once, in an eight-day marathon as a bet with my friends, and while I enjoyed the shifts in perspective the first time around, I wouldn't have thought that the words would mark it out so clearly. I also hadn't thought about Ulysses in religious terms, so seeing the relative prominence of the word "God" in each chapter tells a story I hadn't noticed before.

Cool stuff. If nothing else, with word-clusters like "God Like Mother," "Look Back Sargent," "Eyes Going Kiss," this thing's a band-name factory.