The Life Swap, in paperback. ISO SWF. BYO Knife to ... Stab Me in the Back With.

If I had to give someone instructions for temporarily inhabiting my life, I’d probably start with the small stuff. “Constantly buy produce and then forget to eat it until it goes bad” would be one important point; “Be incredibly attractive to, and highly allergic to, all mosquitoes” would be another. “Dress like a 15-year-old tomboy most of the time, but consistently express surprise when a bartender cards me” might even make the list.

These are just a few of the nitty-gritty incidentals that combine to create my version of the universe. I wonder: how much detail would I have to give to enable someone else to become me for a period of time? Or even credibly pretend to?

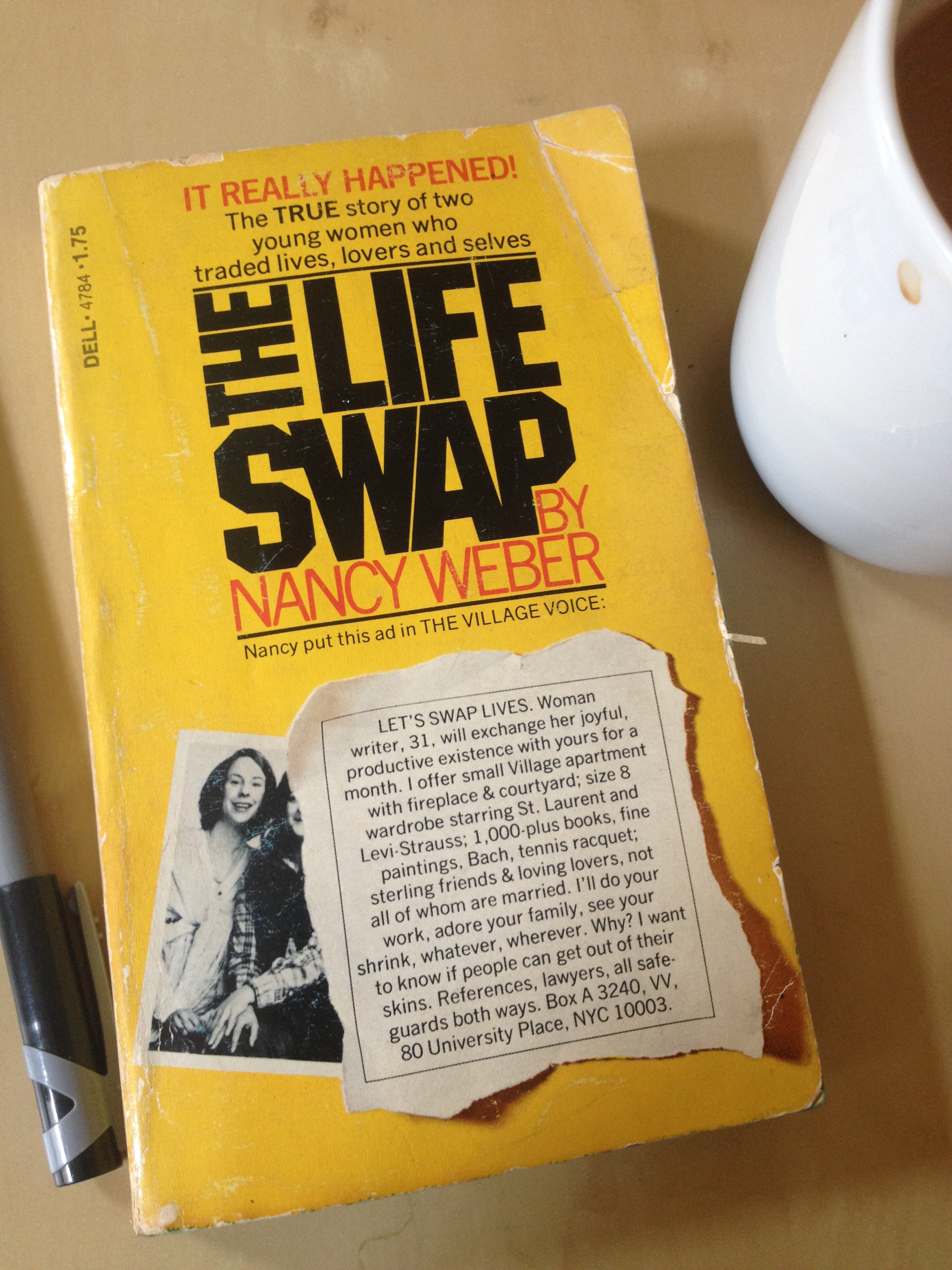

I had occasion to create and revise my mental how-to-be-me manual while reading a weird little gem called The Life Swap, by Nancy Weber. I picked up an original Dell paperback from its first run in 1975 in a used bookstore this summer. Tabloid-red type screams across the book’s bright yellow cover: “IT REALLY HAPPENED!” Below that is the text of Nancy’s ad in The Village Voice that set the whole experiment running:

LET’S SWAP LIVES. Woman writer, 31, will exchange her joyful, productive existence with yours for a month. I offer small Village apartment with fireplace & courtyard; size 8 wardrobe starring St. Laurent and Levi-Strauss; 1,000-plus books, fine paintings, Bach, tennis racquet; sterling friends & loving lovers, not all of whom are married. I’ll do your work, adore your family, see your shrink, whatever, wherever. Why? I want to know if people can get out of their skins. References, lawyers, all safeguards both ways.

As she recounts in the book, she gets a handful of responses to the ad, and follows up on a few. Most people (or their husbands) eventually chicken out. But the back of the paperback displays the original response from the woman who makes the cut:

I am ready to swap lives with you. Have house in Bucks County, apartment in Manhattan, husband in Buffalo, loving lovers here and there. No shrink to see. In fact, I am one. But don’t worry, the work is no sweat. I am already out of my skin, and am willing to try yours.

Nancy meets up with Micki Wrangler (not her real name) and is smitten. She’s a kind of spastic, chatty, bisexual psychologist who teaches feminist theory in a nearby college. She has a husband in the suburbs for the weekends, a live-in boyfriend in the city during the week, and several occasional lovers of both genders. “A formidable creature—cerebral and maniac and very self-assured,” Nancy writes. “Very jazzy.”

They giddily shake on an agreement to swap for two weeks. Printed notes go out in the mail to the two women’s friends and colleagues, informing them of the experiment and inviting them to play along. The people in each woman’s life are asked to address the new, unfamiliar faces with old familiar names, and to have the same conversations with “New Nancy” and “New Micki” that they would normally have. In preparation for this, Micki will be given diary entries and background notes on the important players in Nancy’s life, and vice versa.

Among these innocent bystanders who are being asked to participate in an experiment they haven’t signed up for, reactions vary widely. Nancy’s boyfriend and mother both express the same level-headed concern—namely, that it’s possible for a sane person to have conceived of and printed that ad, but only a crazy person could ever answer it. Nancy doesn’t care. Her excitement about the project grows every day. The only question in her mind seems to be how successful it’ll be.

In her frenzied and, in retrospect, overly-optimistic diary entries early on, Nancy predicts she’ll “be able to be another woman when I’m in her contextual place, getting the responses she gets from the people in her life, obeying her metabolism, wearing her clothes and perfume, drinking what she drinks, doing her work.” These little changes, she believes, will accumulate and bring about larger feelings and actions: “Maybe something as small as a liking for coffee ice cream, something as big as a talent for monogamy.”

Her goals for the project swell to the grandiose: a total, objective analysis and improvement of each woman’s life. It starts to sound like some kind of method-acting-exercise on steroids. “Very important, I’ll also be discovering things about this woman that she doesn’t know and that she’ll now be able to work consciously to amplify or destroy,” she writes. “And she, back in my life, will be making the same discoveries for herself, for me.”

What could go wrong, right? I don’t want to spoil it, but I’ll just say, just about everything. For the first few days, Nancy enjoys the surreal challenge of inhabiting Micki’s apartment, her job, and her several beds—with her husband, boyfriends, and girlfriends. She diligently records her observations along the way (Micki’s husband: lovely, the roaches in Micki’s bathroom: awful) and how she imagines herself transforming as a result of the process (her underarms don’t smell bad without deodorant: pleasant surprise).

It’s when people from Nancy’s life start to break the rules and call her up mid-swap that the shitstorm descends and the book really picks up. Nancy finds out just how badly Micki is behaving in her (Nancy’s) role. Another spoiler: Micki sleeps with most of Nancy’s friends, and reveals secrets from Nancy’s diaries to the rest of them. She vocally psychoanalyzes Nancy and all of Nancy’s relationships, but gets it all really wrong, and makes both Nancy and herself look awful in the process. To top it off, she horribly offends Nancy’s poor father and hits on her mother. It’s really pretty bad. Micki later describes her experience as a kind of spiritual breakdown brought on by Nancy’s toxic life, but it appeared to me to be a sleep-deprivation-induced hysteria in a person who was already sort of kind of crazy anyway. The woman who had first struck Nancy as a breezy, adventurous compatriot for her experiment turns out to be a manic, competitive mess.

“There was a new horror story every day,” Nancy writes during the weeks following the swap. “My friends’ revelations were rivaling the Watergate hearings. Unlike the Watergate revelations, my friends’ all jibed.”

Parts of Life Swap feel dated—particularly some of the debates about feminism. It being the 1970s, there’s a lot of talk throughout about whether to wear deodorant or not, whether to remove body hair or not, and yogurt. So much yogurt! And, being a “woman writer” of 31 in New York City myself, I had to scowl a little at her Carrie-Bradshaw-esque ability to live alone in a West Village apartment with what seemed to be pretty infrequent freelance writing assignments. It was a different time to be a writer, and a different city, then.

Other aspects of the book, though, are absolutely timeless. The voyeuristic pleasure of seeing two lives from the inside, and the dangerous thrill of seeing them both implode, are as fun to read as the best reality TV shows are to watch. The creepy-crawly horror of the damage wrought by a hasty judgment to trust a stranger will be familiar to anyone who’s ever found herself in the midst of a roommate-from-Craigslist debacle.

When Nancy puts an abrupt end to the swap for everyone’s safety and wellbeing, her joy at being back in her own skin is palpable. She’s the original version of all of those women on Fox’s Trading Spouses or ABC’s Wife Swap who return from a tumultuous stint with someone else’s family, smother their husbands and kids in kisses, and breathlessly declare to the camera, “The only think I learned from this swap is that I love my marriage and my kids just the way they are and I’m not going to change a thing!”

Everything in Nancy’s home feels precious to her when she returns. The fresh yellow flowers she always buys for her apartment, and the gloomy painting on her wall that she stares at meditatively while writing. Her drink of choice, Heineken in a goblet with lots of ice. Her favorite perfume, Shalimar, which her mother also wears. None of these things alone define her, but they are all a part of her; they are the tiny blocks with which she’s built her life. Stripped of all of them at once, she finds that she has felt liberated, but ultimately unmoored. Likewise, trying on someone else’s clothes and diet and bedmates has been exciting for a while, but ultimately the experience only serves to affirm her own habits and choices, big and small.

The life swap was a worthy experiment, and is a strange, addictive read. It was an intriguing scenario that I am definitely not tempted to duplicate, however much fun it may be to imagine my own instruction manual or dream up potential swapees. I’m glad that Nancy and Micki tried it so that the rest of us don’t have to. But for Nancy’s sake, maybe she should have just listened to her mother, whose initial reaction to the swap was captured in her own diary entry at the end of the book. “How stupid the whole idea is,” she writes. “We are what we are.”

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©