Reading Padgett Powell’s new book, You & Me, felt a lot like sitting on a lawn chair, slightly drunk, quietly listening to two old and charming men, also slightly drunk, pontificate on life. I imagine Powell, author of Edistoand The Interrogative Mood: A Novel?, reclining in Gainesville, getting down to the true business of what it means to repose.

Fashioned after Waiting for Godot, the book features two unidentified speakers, indistinguishable from one another, who simply speak together. Unlike Didi and Gogo, they aren’t really waiting for anything—except maybe death, a little. Or rather, a state of readiness for death, but only as much as they are waiting for a woman to stop by. The book offers no plot, and yet I felt compelled forward by some strange momentum, and I have some suspicions as to what these mysterious gadgets of momentum might be.

Gadget #1: Charm

I kind of fell in love with them a little bit. I, admittedly, have a weakness for old men, especially if they are tender toward some loss, but the dialogue here is not only funny and intelligent, but graceful and full of the humility of a felt humanity.

You have a wife?

I had a wife.

Oh. Of course. We all had a wife. Wife is a synonym for "past."

Are you in love with them? I am in love with them. I want to bring them blankets and whiskey and perhaps offer snacks later, because they probably aren’t eating enough. Which brings me to...

Gadget #2: Comfort

The interchange here is tender: it is tender between the two men and they are tender towards themselves. They are tender even in their disappointment of people and what life has ended up being.

What about with the exposed Wizard in the basket at the end?

Dorothy never gets in the basket. That’s what wakes her up.

We never got in the basket either, my friend, and that is what has us all woke up. We are looking up at the basket.

We is all woke up and nowhere to go.

It is comforting to listen in on their exchange. Their words are comforting, their philosophy is comforting, their relationship is comforting. This makes for easy reading, but it also helps to propel things along, in that we want to seek out further comfort. Further comfort and simply more words from those who would comfort us.

Gadget #3: Intimacy Over Time

There are various characters and objects introduced over the course of the conversations, such as the imagined character Studio Becalmed, who take on a kind of fullness. But after reading the whole book, I’m pretty convinced that what really kept me reading, excitedly and with pleasure, was simply the desire to spend enough time here, in their conversation, to feel as though I knew them fully enough, and that I was given the gist of all they had to say.

This is why we do not know, have a clue, really, how to live today as if it's the last day of our lives. We think we have the score because we can see that fifty years ago we did not have the score, bolting from the playhouse, but the fact is we are bolting from another playhouse today. We do not even recognize it as a playhouse.

It wouldn’t do to cut these men short. And I don’t think the full pleasure of the encounter would be the same if the story were told in any other way.

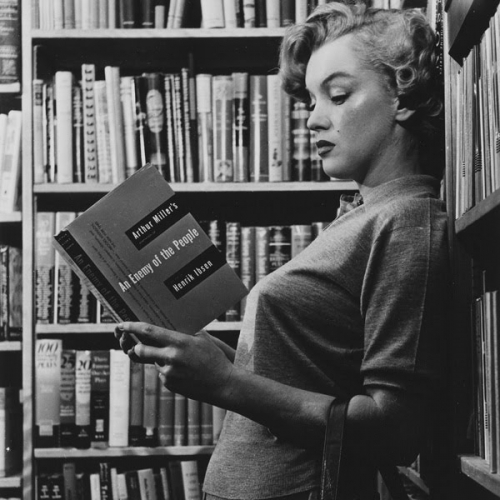

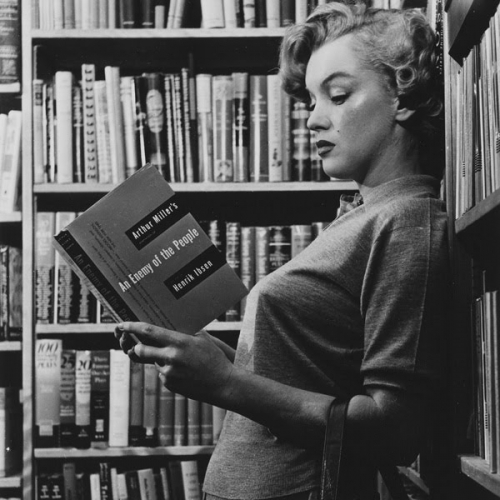

image: startribune.com

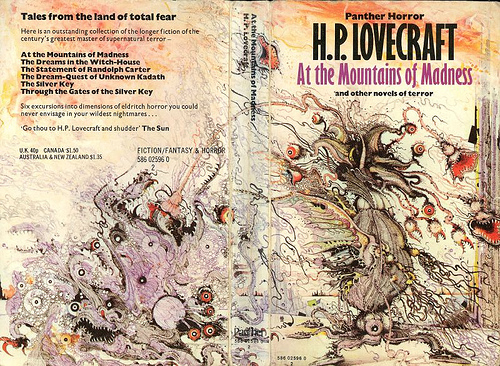

I owe my childhood fear of clowns and feral felines to Stephen King. His brick-sized bestsellers dominated my bedroom bookshelves, although I supplemented historical horror with a leatherbound volume of Edgar Allan Poe. I remember wondering who bridged Poe's masterful 19th-century macabre and King's contemporary terror. Today, King's ubiquity remains unchallenged—New York has ranked his entire published oeuvre, and he's got two novels planned for 2013—but contemporary horror trends contain an undercurrent of something unspeakably scarier, originating from the cosmos-chilled, slime-soaked legacy of the writer who not only greatly influenced King, but has his own sub-genre. I give you H.P. Lovecraft.

King himself acknowledges the genre's debt to Lovecraft in his book Danse Macabre: “The reader would do well to remember that it is Lovecraft's shadow, so long and gaunt, and his eyes, so dark and puritanical, which overlie almost all of the important horror fiction that has come since.” With that in mind, I offer this brief primer to help you navigate the Lovecraftian goo.

The Necronomicon

A purely fictional book of the dead that figures greatly into Lovecraft's work. Consider The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and its central tale “The Dunwich Horror.” A librarian senses “a hellish advance in the black dominion of the ancient and once passive nightmare” upon opening the cursed tome. In Sam Raimi's film The Evil Dead, the titular antagonists are (un)wakened by the Necronomicon, while HR Giger's debut monograph(and painting Necronom IV, which inspired Alien's iconic xenomorph) shares the name. Unfortunately, The Dunwich Horror is also a ridiculous B-movie starring Sandra “Gidget” Dee. Tread carefully with “direct” Lovecraft film adaptations.

A fictional Massachusetts town (like King's Castle Rock, Maine) and the setting for Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. Meet “Herbert West—Reanimator,” who proved “rational life can be restored scientifically," and proceed to the decent '85 bloodbath Re-Animator, but I advise eschewing the slasher atrocity The Unnamable, based on Lovecraft's 1923 story. “The Thing on the Doorstep” revolves around Arkham's sanitarium, preceding Arkham Asylumand its gallery of Batman villains, and its personality-shifting plot is a bit Lost Highway. Just think: Lovecraftian and Lynchian!

Indescribable terror

“The Call of Cthulhu” birthed Lovecraft's famous extradimensional, malevolent entity, yet it simultaneously underscored the crippling bafflement of fear. Here's Cthulhu's setup, after a very late reveal: “the Thing cannot be described—there is no language for such abysms of shrieking and immemorial lunacy, such eldritch contradictions of all matter, force, and cosmic order.” Frank Darabont's 2007 film The Mist, based on King's 1980 novella, keeps its besieging, otherworldly fauna masked by the enveloping haze. Jorge Luis Borges, preeminent engineer of enigmas, dedicated The Book of Sand's “There Are More Things” to Lovecraft. The narrator's abstracted inability to describe a house's monstrous inhabitant recalls Lovecraft's scientific barrage of the frozen...things in his singular novella At the Mountains of Madness: in either case, we are no closer to understanding the horror in front of us.

This brings me to Guillermo del Toro's much-delayed dream-project: translating At the Mountains of Madness to cinema. Despite the aforementioned Lovecraft-flavored films, there's little out there that successfully combines “proper Lovecraft adaptation” with “quality viewing” besides 1992's The Resurrected, which didn't even have a proper theatrical run. Del Toro aimed to change this, but after Universal's balking at the blockbuster price tag and Del Toro fearing similarities between ATMOMand Ridley Scott's Prometheus—which draws tellingly from Lovecraft's “Promethean trespass”—its fate is in limbo.

I'm not ready to close this chapter just yet. If Michael Bay gets the OK to helm yet another schlock-and-awe Transformers sequel—whether or not it stars Rosie Huntington-Whiteley—then I say we need a philosophical sci-fi horror film of ATMOM's stature more than ever. In Lovecraft's words from “The Nameless City”:

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.

Main image: H. P. Lovecraft Wiki + ToyVault, photo-chopped by the author; At the Mountains of Madness via The Furnace

Sorry Please Thank You, a new collection of stories by How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe author Charles Yu, serves up lonesome tales in both science- and meta-fictional landscapes. Whether taken as projections of where we're headed, reflections on how things are, or simply the settings and structures Yu is most drawn to, the worlds we encounter are far from bright. I don't see these stories as warnings—they're more like compassionate takes on human longing and insecurity, regardless of where they fall on the space-time continuum—but I thought it'd be fun to pick out the suckiest aspects of Yu's alternate realities. Things we just might have to look forward to.

Low Wages

In exchange for feeling the worst kinds of pain, pain that people would rather pay someone else to feel for them, the hero of "Standard Loneliness Package" makes twelve dollars an hour. Twelve dollars an hour! Counting for inflation, by the time technology has figured out how to transfer emotion from one brain to the other, there's just no way twelve dollars an hour would be a liveable wage. But of course the corporation still makes millions. Ouch.

Inadequate Flirting

For both the employee of WorldMart and the zombie that waltzes through gussying up for a date in "First Person Shooter," having a little confidence seems to be a big problem. Not the megabox store the size of three city blocks, not that they work the graveyard shift or that they are a zombie (or that there is a zombie), but that they're both terrified of rejection.

Jobs Where You're Basically Signing Up to Die

If twelve dollars an hour to experience other people's anguish wasn't depressing enough, the story "Yoeman" invites us to imagine space jobs wherein promotion leads to inevitable and needless death. As soon as our hero "makes it" enough to take care of his expectant wife and soon-to-be child, he gets to be the one who's killed for no good reason. Or rather, killed because it's nice to have something noteworthy in the Captain's log. We all know how important logs are.

Angsty Avatars

Have you ever wished you could live in a video game? Because it's so straight-forward and has lots of interesting graphics? Think again. In "Hero Absorbs Major Damage," the actual characters of video games question their right to be there and their readiness for the mission. No matter how good Jeff Bridges looks in the original Tron, you're kidding yourself if you think you get to leave your self-doubt in the real world.

Intergalactic Loneliness

Probably the saddest thing is that when we reach the end of the universe, and we've explored it countless times and the excitement has kind of worn off the old "discovery" thrill, there still won't be other people for everyone. Not everyone gets to love. Some people only get some goo they can dry-hump for all eternity, like our poor Captain from "Yoeman." Probably really quality goo though, on the outskirts.

To experience Yu's imaginings in action, check out this samplefrom Lightspeed. It might just make you appreciate the present.

image: io9.com

If it looks like her moods are swinging faster than a speeding lithium, look closer. Better yet, see the whole video when you download theLouise: Amended evolving book app to your iPad. Better still, act fast and you can get the app for free and even bag a $100 gift card to Powell's Books!

Read More

1.

The line might be three people long or thirty. On a ninety-degree afternoon, we waited 45 minutes for second-row seats.

2.

"It's a film made up of clips from other movies," the line attendant told us. "Every clip has a clock, or refers to time, or implies time, and every clip happens at the same moment as the time it is outside. If you look at your watch and it says 2:15, a clip that takes place at 2:15 will be up on the screen. It's connected to a computer program to make sure that the film's always synchronized with the real-world time."

3.

Just before 5:00pm, Steve Martin pantomimed to his business partner that he had to leave for a 6:00 flight. At six, we saw him make it to the gate only to find the flight delayed. What Steve Martin was doing for that hour in between, as we watched clips from the 1960 version of The Time Machineas well as Casablanca and others—well, it’s not hard to guess.

4.

We couldn’t believe how much happened on the screen in ten minutes. How many people sighed, how many people answered phones, how many people watched clocks ticking.

5.

I meant to stay for an hour. The people in the couch next to mine got up and left. A woman sat down there and soon moved to the far end of her couch—a comfortably retired actress, I realized. Was she waiting for her cameo?

6.

We saw actors in different films throughout their careers. Glenn Close has changed. Robert Redford has changed. Meryl Streep has changed. Jimmy Stewart has not changed.

7.

I am a product of the eighties. I recognized the clips from The Matrix andNapoleon Dynamite. If there was any Orson Welles, it was lost on me. I nodded at a two-second clip from Sixteen Candles and a fifteen-second clip from Adventures in Babysitting. My parents are products of the fifties, as well as the decades after. Would they have been even more enthralled than I was?

8.

“Marclay manages to deliver connections at once so lovely and so unlikely that you can’t really see how they were managed: you have to chalk it up to blessed serendipity. Guns in one film meet guns in another, and kisses, kisses; drivers in color wave through drivers in black-and-white so they might overtake them.”

—Zadie Smith, “Killing Orson Welles at Midnight”

9.

The difference between good editing and great editing is a matter of discipline. Of course there are "good enough" transitions, but insisting on the perfect juxtaposition, just like le mot juste, makes a world of difference when attempted on such a massive scale. There is suspense embedded in the film clips, but Marclay's prowess is evident in the perpetual suspense of the cuts between them.

10.

“At Marclay’s request, White Cube posted a 'Help Wanted' sign at Today is Boring, a cinéaste redoubt on Kingsland Road. Six young people were hired to watch DVDs and rip digital copies of any scene showing a clock or alluding to the time . . . At first, he was merely collecting scattered files, but eventually he had enough to forge 'hinges' between them. The more hinges he came up with, the more inventive they got.”

—Daniel Zalewski, “The Hours”

11.

People punch the clock, hit the alarm clock, wind up the grandfather clock, open their pocket watch, move the minute hand forward and forward and forward. Robert Redford hits a baseball through a clock—although, in The Clock, the shards don’t fall in slow motion. It all happens in real time.

12.

“There was not actually such a thing as a second [in the film L'Avventurawhen a twentysomething Geoff Dyer saw it in Paris] . . . A minute was the minimum increment of temporal measurement. Every second lasted a minute, every minute lasted an hour, an hour a year, and so on. Trade time for a bigger unit of time. When I finally emerged into the Parisian twilight I was in my early thirties.”

—Geoff Dyer, Zona

13.

I emerged into the New York twilight three hours after entering, having walked past sleeping hipsters and snacking gallerinas toward the fading sunlight. I took the bus back to my apartment, and saw a row of clocksalong Fifty-Seventh Street, each one set to a different time zone. In my head, I could still hear the ticking.

image credit: flickr.com/billindc

“I don’t want to read a book in translation,” my friend declared. “It’s not as good as reading the original.”

I put down my beer with a thud. I couldn’t even reply. The comment seemed to confirm a depressing statistic I had read in The Economist: “When it comes to international literature, English readers are the worst-served in the Western world. Only 3% of the books published annually in America and Britain are translated from another language; fiction’s slice is less than 1%.”

I wanted to pull out a copy of Anna Karenina—sorry, Анна Каренина—and show my friend the Cyrillic text. I ought to have said, “You mean reading a book you can’t understand is better than reading one you can?” Or, “I can barely correct my brother’s Spanish grammar, and I sure can’t read New Finnish Grammar unless it’s in English.”

Fortunately (or not), I had the self-restraint to change the subject.

America, go to our bookstores and look at the “Classics” sections. Homer,Cervantes, Dante, Flaubert, Borges. We owe our literary history to these authors and the intermediaries—Robert Fagles, Edith Grossman, Allen Mandelbaum, Lydia Davis, Andrew Hurley—who have carried the texts to our Anglophone shores.

It doesn’t matter how many MFA programs we have. It doesn’t matter how brilliant our living writers might be. Our own literature would still be barren without those foreign incursions. Even our earliest English classic isBeowulf, and I read it in Seamus Heaney’s resounding, earthy translation. Ask a budding writer if they’ve read Bolaño, and they’ll most likely nod enthusiastically, half-aware that Natasha Wimmer made possible their enjoyment of The Savage Detectives and 2666.

Among the alarmingly low number of publishers who will do books from other countries, we have Open Letter, Europa, Other Press, and a new player: Peirene Press. The wonderful thing about Peirene is that, although it publishes exclusively literature in translation, it focuses first and foremost on sharing a great story with each book. Their novellas take as little time to read as it does to watch a film, and the publisher holds events to discuss each book. She's a salonniere, and she's a success. She’s actually getting people to read something they might avoid if they knew it was “foreign.”

America, there’s a new direction for us. We don’t need relatable authors; we need strange and wonderful and new stories. I’d rather talk about good books than nice authors any day. Let’s skip the usual crop of MFA workshop pieces about the Brooklyn Promenade.

America, let’s publish Icelandic writers (Steinar Bragi!) and Argentinian writers (Pola Oloixarac!) and Mauritanian writers (Ananda Devi!) and make them worth reading. I wouldn’t know where on the map Iran is, or why I’d want to visit, unless I’d read Censoring an Iranian Love Story. I want to read something nobody in America would risk writing. America, let’s open our eyes to the rest of the world.

America, let’s make foreign literature sexy.

image credit: redsurproducciones.blogspot.com

I willingly do not own a television, but when I visit my family I tend to gorge myself on it. Last Thanksgiving, I watched eight episodes from Season 6 ofKeeping Up with the Kardashians, and somewhere in that miasma of SoCal socialite bliss—episode 3's synopsis: “Kim takes action to prove that her butt is real”—I got to know Kardashian half-sisters Kendall and Kylie Jenner. Beyond their reality TV stint, they've modeled, hosted red carpet events, designed nail lacquers, and contributed to Seventeen. Now E! News has revealed the next logical step: the Jenner sibs are writing a young-adult sci-fi novel set 200 years in the future. As you do.

Khloé, Kim, and Kourtney already penned a novel, Dollhouse, but you couldn't get me to “read” it if you hooked me to a single-malt intravenous and had Gary Oldman perched over my shoulder, reciting their prose dramatically (or Gilbert Gottfried, for that matter). But my inner-dork is intrigued by the Jenner sisters' premise. According to their publisher, who also put out Kris Jenner's ...And All Things Kardashian, “the story will take place in a world none of us have ever seen and it will follow two sisters on a journey filled with terror, mystery, drama and love.”

Just think of the century-specific technology envisioned by these young minds! I'm secretly hoping they take inspiration from Luc Besson's The Fifth Element (also set in the 23rd Century) and feature flying Range Rovers.

But seriously now. The publishers call it “dystopian,” which pretty much screams "Hunger Games ripoff"—a charge leveled at young author Veronica Roth's Divergent. Those questioning how the Jenners could fathom a concept like “dystopia” need only watch the harrowingKardashians episode “The Have and Have Nots,” where Dad makes Kendall and Kylie visit a downtown LA children's shelter. Severely limited "real life experience," true, but maybe they can build on it in their novel. OK, I'm taking a huge leap of faith here.

And they're still teenagers! Their project comes with a cowriter, Maya Sloan (whose own debut YA novel High Before Homeroom has its own book trailer!), but trust in Kris to pull the Overbearing Mom routine to ensure her daughters' voices come through clearly. Plus, their “Fashion Journal” column debuted in the June/July issue of Seventeen. It's a collage ofphotos and quotes, but if the girls can concentrate percolating ideas into chapters (cue cowriter Sloan), they just might create something memorable—and atypically Kardashian.

Image: Kendall and Kylie Jenner via JustJaredJr. + Blade Runner scene viainCrysis, photo-chopped by the author

Flavorwire posted a list of ten of the best books set in the Midwest, and since I’m currently reading Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (#1 their list) and residing in our nation’s heartland (right around where much of Freedom is set), I figured I could help those of you who are unfamiliar with this vast terrain. Here are five things that make the Midwest such fertile ground when it comes to novels.

1. The illusion of safety

Sure, there’s probably less crime (there are, after all, fewer people), but the Midwest is also full of folks less likely to report certain behaviors as criminal. If you have a character who needs to get away with some things, there are a whole bunch of Midwesterners more than happy to look away and tend to their own business, or the neighbors are so far away they’d hardly notice anything awry. This doesn’t mean privacy, exactly; it just means there is more space for those wanting to be left alone. Midwesterners gossip, but we usually don't ask questions.

2. Everybody knows your name

Everyone is in everybody’s shit all the time 'cause they all know each other and there isn’t much more excitement than other people’s shit. If you don’t share with everybody, everybody will talk shit about you. They’re all paying attention. Newcomers and committed outsiders are easy protagonists because it is easy here to rub against the grain.

3. Nature will scare the shit out of you

In the Midwest, nature isn’t just something pretty to describe; it's a force that no one can control and that affects everyone’s day-to-day life. Just askAnder Monson. Nature can be a legitimized mood swing or full-on devastation of life and home. Looking for a villain but don’t want to look too hard? Set your novel in the Midwest and look up. Or down. Take cover and build your ass a canoe.

4. Desire for days

A person cannot help but want something bigger, brighter, and more fantastic if they happen to be confined to the Midwest. Desire will not likely be satisfied here. There will be compromise. The Thai food will not fulfill even your lowered expectations (though if you try really hard you can get great Indian in Ohio and the Cambodian in St. Paul is phenomenal). There is always something better, on either coast, in any big city. All characters must want something, and if your characters reside in the Midwest, they inherently want more. And most of them want out.

5. Space and time (way too much of them)

This is how John Jeremiah Sullivan describes his home state: "when I say "Indiana"…blue screen, no?" There is little to blame frustrations on other than yourself, and yet there is also little to be distracted by, so you’re constantly aware of your own failure/discontent/alcoholism. What’s wrong is your soul: your natural, uncomplicated, and unfettered soul. In a true Midwestern novel, it’s not society that’s fucked; it’s people. I like to think of this as clarity, and it’s great for fiction that strips off the superficial nonsense and cuts right to the bone.

Image: foxnews.com

Here at Black Balloon, we like pushing the boundaries of what a book can be. We think our evolving e-book for Louise Krug's new memoir, Louise: Amended, does just that, so we're very excited to share it with you—so excited that, for the next two weeks, we're giving it away as a free iPad download! But wait—there's more!

Read More

Jay McInerney, writing in the Guardian last month, tried to understand the enduring power of The Great Gatsby. His answer was writerly: it's the prose, stupid. "Without Fitzgerald's poetry," McInerney says, "without the editorial consciousness of Fitzgerald's narrator Nick Carraway, the story can seem threadbare and melodramatic."

Read More

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©