Wikipedia, the scourge of teachers who still give writing assignments (as if students still had a chance of becoming literate), cannot rely solely on the blood, sweat, and wikitears of its editors alone. There's simply too much content: as of now, that'd be over four million articles in English alone, plus at least as many in other languages. The English edition, if you printed and bound it, would fill almost nine library shelves. So, according to a recent BBC News Magazine article, the Internet encyclopedia now runs with the help of bots.

Essentially, the bots have to be used because of the logistical massiveness of the encyclopedia. Its contents can be edited by all the people who read it—which means, if you think about it, they should be as tagged, graffed, and marked up as the stalls in your favorite dive bar: FREE ART DEGREES, DREAMERS should be written next to every figurative roll of toilet paper on every page of Wikipedia, right? Somehow, it's not.

The relative cleanliness of Wikipedia is due in large part to the bots—armies of them lurking behind the scenes, looking out for changes to articles that are irrelevant or offensive. Gone are the days when you could squeeze "phuque" into your hometown's demographic chart or kill a lunchbreak by putting dick jokes into Anthony Weiner's page, and gone are the days when you could put the name of your arch nemesis on the list of prominent war criminals. So much for those shitzingigz.

Of course, Wikimedia stresses the fact that the bots are not calling all the shots, and that human editors are necessary to retain the polish—such as it is—of the site. And you might think that that is going to be the case for a while. Except you're probably wrong. Bots are already writing effective articles, covering things that no human would really want to write about. Like little league games.

Once the robowriters start breaking into a more general writing field—I'm guessing that romance and thriller genres will be the first to see commercially viable, algorithmically generated content—the literary landscape will change at an even more rapid pace. You thought eBooks were the end of novels? Wait till a bot compiles a narrative specifically honed on your Amazon buying habits.

In response to this technological marvel, writers will probably become more formally experimental, seeking to convey in ways that escape conventional tropes. (Yay. For. Poetry.) And their audience will probably take renewed pleasure in standing in the same room with them, knowing that the words they savor are the work of a fleshy primate. (Hasta la vista, mass-culture.)

Image: but does it float

I've been writing about language usage for the last two weeks, spurred on by Steven Pinker's critique of a New Yorker piece on the divide between prescriptivists and descriptivists. Last week, I argued that patterns of speech are not just abstract tools; they actually constitute part of our bodily identity, which complicates claims about what constitutes good speech. This post looks at how we can still probe language and give it some measure, even if the tools we have are as culturally particular as Samuel Clemens's psuedonym.

How you speak lets the world know who you are. Even if you switch accents as often as this kid, you reveal your origins with the idioms you use. You could be a non-native speaker, a b-school d-bag, a busted urbanite, a grifter whose slithering turns of phrase endear you to anyone with a susceptible ear. However you speak, we have the sense, egalitarian-minded that we are, that it is illiberal to judge you for idiosyncrasies outside your control—your place of birth, your heritage, your parents’ linguistic tics.

This is why language standards are such difficult pancakes.

Yet, there is the problem of taste. Sometimes you have to wonder why certain gestures really hit you in the gut but glance right off other people. There's no single metric of taste, but thankfully there’s something better: understanding the process through which aesthetic judgments are affirmed or disavowed. You can account for taste, even if it involves complex exchange rates.

Here's how it works. Taste is at once an inversion and a strengthening, a way of self-reflectively relating your own appreciation of a thing to that of others—specifically, the peers whose opinion you wish to garner, passively or not. So when you're looking at a piece of art, you gague your own reaction to it and simultaneously measure that feeling against that of the people to whom you'd like to appeal—in both senses: you want your judgment to be appealing to them, and you appeal for their support in having made it. In doing so, you're providing judgments about things that other people use to inform their own tastes. Sort of like dumping a bucket of sand onto the beach on which we're all making mud castles: it's good to have dirty hands.

Once you realize that taste is endlessly being reshaped through the intentional effort of many people, yourself included, you're all set to take on prigs and pedants. Suddenly, their bugbears are mere historical contingencies. "That" and "which," for instance: someone at some point assured us yanks that these were distinct, even though the record of written and spoken American English upholds no distinction. Count it another quixotic case of prickly genteel folk attempting to swim against the linguistic tide.

Speaking of "quixotic," consider a cherished old volume of mine, Fowler's Modern English Usage. The second edition, printed in 1965, calls out people who pronounce Quixote as it would have been pronounced in Spanish for "didacticism." Now, a mere half-century later, people who don’t give a Spanish pronunciation to Cervantes’ character would almost certainly stand out as unschooled.

Other manuals fare poorer. Strunk and White's The Elements of Style wears its convictions on its spine: here is a unified manual of stylistic concerns, rendered in their simplest components. Unfortunately, the book itself is riddled with tips and tics that are just plain wrong.

Garner's Modern American Usage values communication over avoidance, and even helps people know exactly how out of touch their grammatical foibles are. While verging on the pedantic, it has no pretensions about preserving an ahistorical version of language. For words like "enormity,"famously misused (or was it?) by President Obama, Garner’s includes a scale laying out how acceptable the usage error is. You can feel safe indulging your peevological urges if something has low broad acceptance, but once something is as gone as the distinction between nauseous and nauseated, you better let it go.

Usage guides, and the people who love them, have got to take into account the way language evolves. After all, we just want to communicate as clearly and effectively as possible—which means in full awareness of the way language is made on all of our tongues. Hopefully, we can agree on that.

New rules for fulfilling your creative dreams: 1) work when you're tired; 2) work when you're buzzed; 3) forget everything you learned in school.

Read More

Last week, I mused on Steven Pinker's critique of a New Yorker article on descriptivist and prescriptivist ways of thinking about language. Pinker came out swinging against that simplistic dichotomy, which is fine and dandy, but I had some qualms with his take on "standard English" (to wit: comparing the tacit rules of language to traffic patterns is a category mistake). Today, I want to talk about how we talk, and what that says about us.

People are brought up within a specific cultural environment, taking its imprint into their bodies—where you're from and how you come to know yourself wires your brain—and enacting its common codes as their habits, trains of thought, manners of speaking. These things, among them tacit rules of language, are in a real sense enfolded, engraved into the flesh. To say that a person ought to talk according to a standard that is not their own is far more alienating than telling them, for instance, to use the metric system. It is to say that those of us who didn't come from the right milieu must remake our sense of and capacity for self-fashioning. We must become what we were not, in terms we would not use.

At least, if we want to prosper ’round here.

Anybody who’s struggled to disentangle all the likes knotted into their speech after a California childhood knows how difficult it is to remove a single word, much less syntactical patterns. Besides, they are intimate indications of a person’s background: the lingering y’alls in a former southerner's worn-through drawl indicates to anyone with an ear for it where they’re from. To recognize dialect and accents—to appreciate the pompous way the guy your friend is dating always uses shall instead of will—is to recognize a linguistic territory, geographic or socioeconomic or affinitive or otherwise. And the range and variation of each contributes to the overall richness of language as a whole: each differentiation swells the sense of words and the ways they signify.

Still, there’s something compelling about the notion of a “standard English.” This shouldn’t be convincing on the face of it. What’s gained if we all converse or write precisely alike, noting with obsessive care the pedantries of long-dead, only ever partial, savants? What’ll we lose if we don’t?

Language lives and floats on the breath of those who speak it. It is continually being remade as it is exhaled from humid, living lungs, and, being caught up with the formative experiences of speakers’ identities, it comes to reflect the broader trajectory of the mouths that speak it. A lot of the shrillest warnings about language usage faltering merely indicate a shift in dominant trends, even if those issuing them would tie that shift to a decline in civilization. And disparaging specific patterns of speech as uneducated, ill-suited for high paying work, or essentially different—when in fact the only difference they signify is the history of the person that would say them—is lame. There is nothing, as Pinker says, inherently wrong about one manner of speechifying, so long as it makes sense. (Fine, this is notalways the case; more on that next week.)

What does this leave those of us who’ve grown fond of our Fowler, our elementary styles, our usage manuals, who are invested in aesthetics, in really getting down to the right stylings of linguistic awesome? It leaves us the flow of language use, past senses coursing toward future ones, and that is a turbulent current. But it is something, if you know how to fathom it. Mark twain, motherfuckers.

Stay tuned for the final installment of this series, coming at you next week.

Image: A Niagara of Alien Beauty

Steven Pinker recently released a salvo against The New Yorker, following Joan Acocella's piece on "proper" language usage. I appreciated Pinker's rebuttal, because I have a reflexive distaste for the insular, middle-length thinking that magazine inculcates in its readers, and because, more than anything, I can't stand language prigs—whether they’re lambasting each other over misperceived errors regarding the plural of "vinyl" or one-upping each other in the quest for stylistic purity by avoiding the prepositions with which the rest of us end sentences.

Why? Because, frankly, they’re wrong.

Pinker’s issue with The New Yorker concerns a supposed opposition between “descriptivists” and “prescriptivists”: respectively, those who think the best way to understand language is with descriptions of how it is actually spoken, and those who want to fathom the real laws of language and judge existing speech or writing accordingly. This opposition is old as the hills and, like many such conceptions, it isn’t really accurate. Nowadays in linguistic studies, things are not so dichotomous. This makes sense: in order to suss out formal rules, you need to approach the seething linguistic morass that gurgles outta people’s throats, and in order to describe how that morass functions in life, you outline patterns that, like it or not, regulate the way words work. And most people who actually delve into language are not so cavalier about claiming to know the final truth about the right stylings of linguistic awesome.

The thing is, Pinker errs in his endorsement of a "standard English." What would that be, anyway? The difficulty with his position reveals itself when he likens “conventions” such as standardized weights and measures to the tacit rules that govern expression within a community. Take, for instance, this analogy encouraging “standard” usage:

But the valid observation that there is nothing inherently wrong withain’t should not be confused with the invalid inference that ain’t is one of the conventions of standard English. Dichotomizers have difficulty grasping this point, so I’ll repeat it with an analogy. In the United Kingdom, everyone drives on the left, and there is nothing sinister, gauche, or socialist about their choice. Nonetheless there is an excellent reason to encourage a person in the United States to drive on the right: That’s the way it’s done around here.

See: there is nothing inherently wrong with either, but we would be poorly advising people if we told them that they could drive on the left in the States. It'd lead to horrific collisions, or at least make road-texting that much harder. Sad.

Problem is, this isn't really apt. Manners of speaking reside far deeper in our psyches, constitute much more of our identities, than familiarity with driving on the left or right side of a strip of asphalt. They constitute our very capacity for describing ourselves, our lusts, aspirations, sexual fantasies, fealties, and relation to the divine. (Intimate things, those.) Nor is language learning managed by the ISO, or other bodies that govern the “conventions” to which Pinker compares standard English; there have been no agreements about what words should be said to infants, and in which order, and it’s unlikely there will be. Hence, the way we speak isn't a practice that can be instrumentalized like driving within a territory—though perhaps children shouldn’t get a speaker’s permit until they turn 15, and only after a bleak, Red Asphalt-style course on hurried sentences and the influence of alcohol on utterance.

Somehow I don’t think that’s likely scenario. And somehow I don't think hearing ain't used in a sentence causes many semis to swerve into oncoming traffic.

Watch this space next week for Part 2 of "Describing Your Prescriptivism."

Image: Planet of the Apes

Craig Mod sings a funeral dirge for book covers, yet another beautiful casualty of the shift toward digital distribution of “books.” Because they have lost their purpose, covers must die: as bookstores finally succumb to the efficiencies of Internet distribution, book covers themselves will lose the emphasis they currently have in the publishing world. Instead, clever designers will continually tweak covers—or app icons?—to leverage the characteristics of whichever particular method of distribution—Kindle, Apple Store, whatever—to their favor. Or so it would seem.

I wonder about this. I'm not so sure that major publishers will be keen to give up the "branding" achieved by iconic cover design. While Mod is definitely correct that the cover image at an Amazon book page doesn’t dominate your impression the way physical covers do when you approach a table display, I think he trivializes its importance. When you search for a book, there is the momentary, all important recognition of a particular cover: I want this edition; I recognize that book. And I bet, as was shown with comprehension and retention of hypertext compared to linear text, that the much vaunted “data” presented to customers on a typical Amazon book page rarely enters memory or affects cognition or purchasing behavior—at least, not as much as the initial impression of recognizing the book’s cover does. Certainly someone at Amazon has metrics on that. [See note on metrics below.]

It is this snap of recognition that makes bestsellers. The industry knows this. Hence, the dextrous marketeers have worked to craft immediately recognizable bestsellers through standardizing distribution channels, optimizing displays, and studying consumers perceptual habits. Marketing departments will want to continue to have control over of each book’s brand, hoping to win the lottery by hitting on the next Fifty Shades of Grey,Harry Potter, Twilight, etc. Covers will still get the most design attention, even if their function and role are in transition for some time.

Still, many of the observations Mod makes about the ghostly controls on electronic books are apt. For instance, the Kindle opens directly to the first page of text—I wonder if publishers make this choice or if it is an aspect of the product they’ve ceded to end retailers, along with price—tucking away the front matter and indicating that the information it contains is of little use to the usual reader. Who knows how to decipher that Library of Congress info, anyway?

Anyway, covers. We may mourn them. They’re doomed because they’re not essential to the non-object ebook. Virtual guts need no physical protection as they’re removed from a virtual shelf and “opened.” And it’s hard to see how methods of preventing remote deletion or emendation of your library would be integrated aesthetically into overall book design.

But fear not. You can still sticker your device.

[Note on metrics: There’s a difficulty in leveraging them as efficiently as possible. Publishers may well be interested doing so through the perpetual refinement of "customer experience" through things like A/B testing. Because of the constant accrual of data about customer behavior that is harvested, there is enormous potential to positively encourage sales. By having two versions of a cover and tracking if either seriously outperforms the other a retail site, marketing teams could, hypothetically, select the cover that performed better and make it, thereafter, the official cover for the book. Problem is, I doubt that Amazon or the other end retailers of ebooks would be enthusiastic about freely sharing the info they gather on customers. So there’d be less integration of data into decisions about which cover did best where. And I doubt publishers will be eager to cede ultimate control over their covers to Amazon, et al. Of course, this isn’t a problem for Amazon’s publishing wing. Then there’s the insidious side of A/B testing. It happens so fast now that marketeers rarely take the time to think about the why B outdoes A in this instance. This is because, essentially, why don't matter. Final causes aren’t as important as immediate effects—namely, money for the company—and so don’t need to be investigated. The danger of this is that marketeers tend lose sight of the fact that they have an impact on the results: you put meat and potatoes in front of a hungry person, they're going to eat it.]

Image: etsy user ilovedoodle

The Nation has devoted a substantial chunk of their new issue, including a post-apocalyptically gloomy cover, to the subject of the most revered and loathed retail behemoth on the planet. The issue, "Amazon and the Conquest of Publishing," offers three long essays on Jeff Bezos's company's origins, controversial labor practices, tax-evasion efforts, data mining tactics, and its conflict-of-interest-y slouching towards publishing its own titles. (Sidebar: Amazon quietly bought Avalon Books, an imprint specializing in romances and mysteries, this week.)

The best and most comprehensive of the essays is Steve Wasserman's "The Amazon Effect." Wasserman, a former editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review (which folded its print edition in 2008), paints a startlingly dystopian picture of Amazon as a company which, like its social networking counterparts, seems to harbor a sinister messianic ambition for itself, a desire to braid itself into our neural pathways.

From street level, they seem to be succeeding. Amazon has always seemed to me less a company than an idea. As Wasserman notes, it has no physical space (at least none that it pays fair taxes on). No one walks into an Amazon store; there are no Amazon greeters. And news that the company would like to replace its human workers, ostensibly the ones who saran-wrap your paperbacks to pieces of cardboard, with robots, hardly surprises, even if it is speeding us towards a vision of the future that would have made Aldous Huxley give us a withering look.

And it seems as though Amazon is banking on the fact that, like it's social network counterparts, it has become an idea, an ingrained feeling, a Pavlovian reflex—a verb. "To Amazon," in my working definition, might refer to "the immediate silent flush of gratification felt upon purchasing a dozen books one has been meaning to read with only a few clicks of a mouse, some of the books hard-to-find novels at scandalous mark-downs."

My sensitive information is saved on the site; I click hectically through to checkout, not the least bit anxious that Amazon has this information, maybe even a bit annoyed to be reminded it does, because a kind of anticipatory saliva has already started accumulating in a part of my brain I didn't know existed before Amazon. Finally, the words "free shipping" mitigate any subsequent feelings of buyer's remorse I might feel as the confirmation emails start cluttering my inbox. My wallet has not moved from my pocket. I have not moved from my chair. Twelve books are on their way to me, and nevermind that it might realistically take me several years to finish them all (in between reading the other stacks of books I ordered last month, and the month before, etc.). The shipping was free. I win.

Understandably, Amazon has its evangelizers, people like Slate's Farhad Manjoo, who argued several months ago that Amazon is "the only thing saving" literary culture, because the company has increased the number of books people buy, which (fishily) leads Manjoo to wish death on public spaces that encourage the buying of said books, a.k.a. independent bookstores. (This seems especially fishy given that said journalist writes for said website which, he admits, is in business with said online retailing behemoth.)

You might recall that this is the same article in which novelist Richard Russo is taken to task for a New York Times op-ed in which he pleaded the case for independent bookstores, the same Richard Russo who spoke at BEA this week, urging publishers to "find a spine" against the Amazonian bully.

But Manjoo is right: Amazon is, in many ways, the ideal friend and accomplice to young literary persons of the Great Recession era. The company appeals seductively to our general poverty, agoraphobia, sense of entitlement, and desire for immediate gratification. And with e-books, which, unlike toaster ovens, can be downloaded to your Amazon Kindle™ instantaneously (in a proprietary format locked to other e-readers), you don't even have to get up and run an illegible squiggle representing your signature™ across the UPS™ guy's Delivery Information Acquisition Device (DIAD)™.

A number of us who return again and again to Amazon aren't even lazy or agoraphobic; we're just broke. We go to our independent bookstores to browse and read on the big "poofy" (Manjoo) couches, buy a coffee, engage the sales attendants in English major banter: a combination of activities which we like to think of as "showing our support." And then we go home and buy a dozen books in a few clicks from the enemy.

What to do, Independent Bookstore, when my heart is your husband, but, as Bezos knows, my wallet's a slut?

According to a highly dispiriting article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, "the percentage of graduate-degree holders who receive food stamps or some other aid more than doubled between 2007 and 2010."

Read More

Ah, flash fiction—or, if you prefer, micro-fiction, short-shorts, prose poems. Or, if you're a little skeptical of the whole genre, "writing exercises." The practice has existed longer than our short-term cultural memory reaches back, and it has spawned publications, websites and brands, like Smithmagazine's Six-Word Memoir. And as of right now, this svelte form has been given its own day. May 16 (or "16 May," in deference to our friends across the pond) is National Flash-Fiction Day. Don't worry, you didn't forget. You didn't know about it because this is the first year for the UK-based event.

Here's what the organizers have to say about this new holiday: “[I]n recent years, with the growth of the internet, more people reading on e-Readers and mobile phones, and the sheer pace of life, the very short story has taken on a life of its own. And we now think this is a life worth celebrating.”

No reason not to dedicate a day to these little nuggets, some of which can be quite inspired. Hell, compared with Twitter, flash fiction can come off like War and Peace. But herein lies the danger of championing flash fiction as a genre. There's much to be said for writing an evocative, arresting short scene, but giving readers a reason to remain interested in your words—dare I say, committed to them—requires a bit more endurance and, frankly, talent.

To me, there's a big difference between being a good writer and a good storyteller. Good writers know how to string together words properly. It is the storyteller that synthesizes the many moving parts of a long-form story or novel and brings into focus areas of our own lives that we didn't realize were out of focus. Great micro-fiction might spark some such sensation, but it doesn't last long enough to ignite.

It is de rigueur to bemoan the lack of time we have in this culture of instant gratification and info-ADD. While I would never dream of thwarting another person's creative release, I do think we should classify these short offerings as a component of a serious storyteller's tool kit, albeit an important component. If we are to rally behind these groupings of a few hundred words, let's encourage them to be used as building blocks that can be incorporated into something larger, more sturdy and lasting: a story we can get lost in and be challenged by.

Yeah, yeah, I know, the definition of a “short story” is up for grabs and plenty of people will want to call me out for being cursory. There are plenty of flash fictions that tell stories in which dramatic tension is introduced and resolved. They can be creative, fun and sometimes even memorable. But think of it like this: Would you rather spend the rest of your life eating nothing but cotton candy or three square meals per day?

So on this micro-auspicious day, go out and flash yourself silly (but don't blame me if you get arrested). And on May 17, get back to work.

Image: nationalflashfictionday.co.uk

Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century, brilliantly translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia, is out from FSG this week. In it, a translator and all-around dandy finds himself romancing a beautiful (and already engaged) woman in the "moving city" of Wandernburg, Germany. All the while, he attends salons to debate about art, philosophy, and other questions of the nineteenth century, and wonders how to escape from the ever-shifting locale.

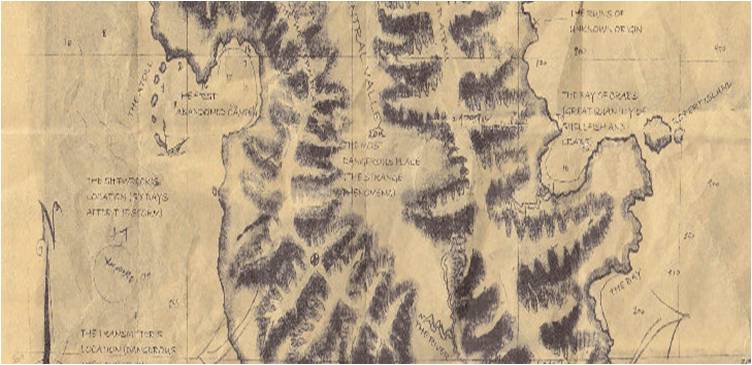

It occured to me that Wandernburg is the latest in a long lineage of uncharted territories, so I've put together a brief history—from Laputa to Lost.

Laputa, from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

"The reader can hardly conceive my astonishment, to behold an island in the air, inhabited by men, who were able (as it should seem) to raise or sink, or put it into progressive motion, as they pleased...it advanced nearer, and I could see the sides of it encompassed with several gradations of galleries, and stairs, at certain intervals, to descend from one to the other. In the lowest gallery, I beheld some people fishing with long angling rods, and others looking on."

In the third book of Gulliver's Travels, Swift satirizes the stormy relationship between England and Ireland as a large landmass and an airborne island. The latter, which also satirizes the Royal Society, boasts such eccentricities as "a shoulder of mutton cut into an equilateral triangle" and workers "softening marble, for pillows and pin-cushions."

Lincoln Island, from Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island

"The balloon, which the wind still drove towards the southwest, had since daybreak gone a considerable distance, which might be reckoned by hundreds of miles, and a tolerably high land had, in fact, appeared in that direction...They were ignorant of what it was, whether an island or a continent, for they did not know to what part of the world the hurricane had driven them. But they must reach this land, whether inhabited or desolate, whether hospitable or not."

After a disastrous balloon flight, a group of explorers lands on a deserted island somewhere in the South Pacific, and—in line with Jules Verne's boundless optimism—makes buildings out of bricks and even constructs an electric telegraph. However, the island abounds with mysteries (such as a pig with a bullet in it) and the group must figure out where the other humans are, if there are any at all.

The city Earth, from Christopher Priest’s Inverted World

"[I]t was clear that the rest of the tracks led along a downhill gradient. In due course the final pulley was removed, and all five cables were once again taut. There was a short wait until, at a signal from the Traction man at the stays, the slow progress of the city continued…down the slope towards us. Contrary to what I had imagined, the city did not run smoothly of its own accord on the advantageous gradient. By the evidence of what I saw the cables were still taut; the city was still having to pull itself."

"Earth" in this science-fiction novel refers not to a planet but to a city that moves on tracks at a controlled rate toward an unknown destination. Hundreds of guildsmen must lay tracks ahead of the gigantic structure, and remove the tracks that have already been crossed. In this strange universe, distance literally becomes time—"I had reached the age of six hundred and fifty miles" is the first line—and the ramifications of this city's perpetual movement into the future become increasingly bizarre.

The Island, from Lost

"I've looked into the eye of this island, and what I saw was beautiful." —Locke

When an airplane going from Sydney to Los Angeles crashes on an island in the South Pacific, survival is the first aim of the marooned travelers. But this TV show, which owes an obvious debt to Jules Verne's earlier island, slowly reveals bizarre phenomena—Arctic polar bears, a metal hatch in the jungle's ground—and suggests a very a disturbing reality. The show itself becomes increasingly disorienting, switching from flashbacks and flash-forwards to flash-sideways storylines as it becomes clear that the island can move in time as well as space.

Wandernburg, from Andrés Neuman’s Traveler of the Century

"Wandernburg: moving city, sit. approx. between ancient states of Saxony and Prussia. Cap. of ancient principality of same name...Despite accounts of chroniclers and travellers, precise loc. unknown."

In comparison to these other fantastical inventions, Andrés Neuman’s uncharted city seems positively pedestrian. Although storefronts and streets switch positions overnight, the city as a whole remains relatively moored on land: Hans, the eponymous traveler, is able to send mail to and from various cities in Europe. The focus is less on an isolated space in the world than on an isolated space in the philosophy and intellectual discourse of the nineteenth century. As Hans sits between two countries, so he translates between many languages and the novel itself melds the details of nineteenth-century doorstops with twenty-first-century novelistic techniques. The result is an enthralling epic of a man who bridges gaps of all sorts while looking, always, toward the future.

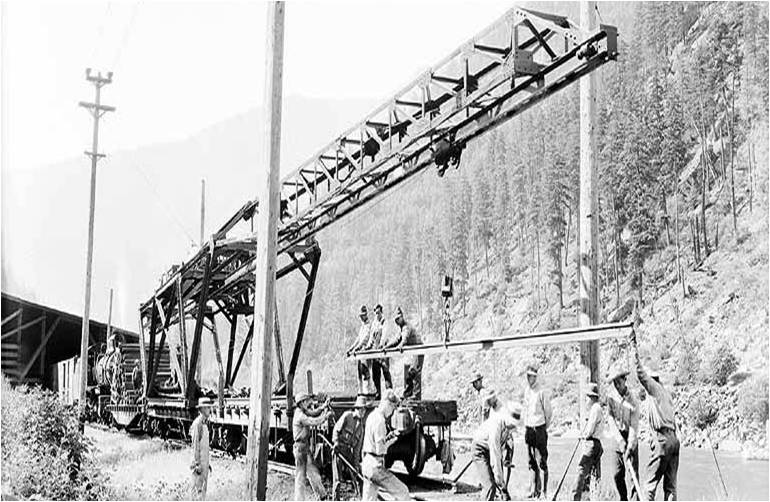

Image credits: Gulliver beholding Laputa, wikipedia.org; Laputa map, books.google.com; Mysterious Island map, verne.garmtdevries.nl; Great Northern Railway track-laying image, lib.washington.edu; Lost island map, lostified.com; Andrés Neuman photo, nutopia2sergiofalcone.blogspot.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©