“Okay, Mr. Shteyngart, can you please remove your pants?” Ever compliant, the Super Sad True Love Story author drops his designer jeans to reveal that he is wearing…what?

Does a certain contemporary Pushcart Prize-winner still wear Underoos? Does the latest Pulitzer-winner prefer the silkiness of Victoria’s Secret panties against his hairy nether regions?

Wouldn’t you like to know.

Recently the Financial Times and the New Yorker featured profiles of writers and their libraries, hoping to unlock some great secret about what book collections say about their curators. Voyeuristic bibliophilia at its geekiest. Yet we don’t learn anything new about writers: they own a lot of books; like to talk about books; think Chekov was a genius (fair enough); and feel like they haven’t read enough books.

So rather than invade writers’ libraries, why not launch a literary panty raid? Invasion of privacy issues aside, analyzing undergarments might reveal far more about our favorite writers and expose what kind of creative stuff they are made of. “Scandalous!” cries Oates. “Okay,” mumbles Roth, loosening his belt. “Undergarments?” queries Boyle.

Kenneth Grahame, author of The Wind in the Willows, supposedly changed his underwear only once a year. Evidently his underwear became a type of protective second skin he was reluctant in shedding. And Jane Smiley writes in a robe—or perhaps even less. She’s rather vague about it.

Looking back, I imagine that Hemingway went commando or strapped on some sandpaper. Something rough and uncomfortable yet oddly liberating, the feeling of which helped him keep his prose economical. Tolstoy, too, probably free-balled it under his coarse peasant garb—a vain attempt to rid himself of impure sexual thoughts.

Other writers, however, must have required some type of confinement. Jean-Paul Sartre probably preferred Gauloises-singed tighty whities, something that undoubtedly irked Beauvoir’s more refined sensibilities. And I like to imagine Edith Wharton and Virginia Woolf shielding a secretive sensual side, burying sexy lace buried under heavy woolen skirts. Much like their prose, both women harbored fiery passions beneath stoic veneers.

Or there’s the curious case of John Cheever. As a young and poorly paid writer, Cheever donned his only suit in the morning to commute to the building where he rented a room in which to write. Upon arriving, he would undress and carefully hang his suit. Then he would sit down and write. “A great many of my stories were written in boxer shorts,” Cheever wrote in1978.

Our contemporary literary giants should be as forthcoming about their unmentionables. What was Underworld written in, or IQ84? Given the massive girth of his latest tome, I imagine Murakami required something roomy and durable. Perhaps a simple pair of cotton Hanes boxers or, ideally, his awesome red running shorts.

Photo: Jaunted

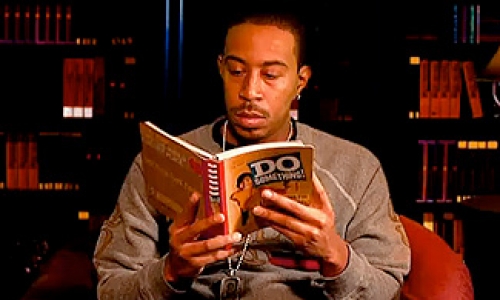

When Notorious B.I.G. posed one of the most famous rhetorical questions in hip-hop history—"What's Beef?"—I wonder if he had any idea that the answer would one day be "syntax and intellectual property." But syntax and intellectual property were certainly at the heart of Ludacris's beefy new diss record aimed at younger rappers Drake and Big Sean.

Read More

When it comes to understanding art, the best intelligence I can muster compares to that of a wildly imaginative but heavily sheltered five year-old. Confronted with the work of someone like Maurizio Cattelan, whose retrospective is up at the Guggenheim through January, I’d rather not be alone with it. Someone else should be there, holding my hand, condescendingly telling me what the fuck to do with it.

I mean, I know all about the color wheel. The color wheel doesn’t faze me. Photographs are simps because photographs are immediate; they have beauty or depth or they don’t. But objects? I have to interact with objects? Immediately, upon encountering things constructed or appropriated as art, I assume there’s something going on—likely something obvious—that my wee brain has zero access to.

Image courtesy of artdatabank.blogspot.com

As much as I have this hesitating self-consciousness, I also suspect that intellect, in the face of art, doesn’t count for shit. And that my encounter with art, regardless of how much of an idiot I appear to be, should a) occur absolutely between myself and the art alone and not with a hand-holder and b) provoke a good deal of feeling. Art can provoke thought too, of course; thought’s okay and all, but it can’t only do that. I can bravely go forth and encounter art—even objects that are art—because it’s the art’s job to move me. Art has to seduce; it has to capture my attention with enough authority and grace for me to want to remain in the encounter for as long as possible.

Image courtesy of artdatabank.blogspot.com

If I were honest about my feelings toward Maurizio Cattelan, I would begin by confessing that I simply enjoy the sound of his name. Second, rumor has it he’s a bit of a hot mess who’s kind of consistently giving the art world the finger, which to me communicates charm. I was hesitant to encounter all of his work all at once; I would have preferred to take each piece on its own. Surprisingly, after the overstimulating first attack, which serves its own interesting purpose, I actually found that encountering the pieces all at once granted a sort of permission to peruse at leisure. I became more open to actually engaging with each individual piece because of the nonchalant, clusterfuck mess of it.

But most importantly, I have a hard time looking away from the elephant.

Image courtesy of artnet.com

I can’t get into the gamut of what happens in my heart and my head, because that’s between me and the elephant. All I can tell you is that I need to go look again, because the elephant hasn’t stopped the promise of telling me everything terrifying, everything beautiful.

“Am I allowed to say that Justin is God?” That’s Rufus Wainwright, quoted on the back cover of Justin Vivian Bond’s new book, Tango: My Childhood, Backwards and in High Heels. “Guardian angel” might be a little more accurate than “God,” considering how widespread Bond's visage has become over the last decade.

Read More

“Damn, the new Wilco album sounds like the seventies,” a friend recently complained to me. “And not in a good way. It’s like Tweedy discovered the cosmic Bowie vibe, a bit of glam rock, and some pseudo-jazz shit and is trying to concoct something new. But I just can’t tell what’s really new.”

Simon Reynolds would probably agree. In his fantastic book, Retromania, Reynolds laments the demise of originality and innovation in today’s music: “Could it be that the greatest danger to the future of our music culture is …its past?”

Perhaps we’re simply slogging through a purgatorial era of the eternal recurrence of past styles and sounds until we can no longer separate the vintage from the retro and we yearn for, and create, the next tectonic shift in music culture. Until that apocalyptic moment, we have Nick Barbery’s blog, ghostcapital, to guide us through some of the quarries of past music cultures, sans condescending irony, to (re)discover music that has been lost, forgotten, or altogether ignored—music that has thus far escaped the perils of retrofication.

As Aquarium Drunkard blogger Justin Gage remarks, ghostcapital exposes the “secret shafts of psych, folk, blues and beyond.” With the likes of Syl Johnson, Karen Dalton, Blackrock, and Judee Sill, these "shafts" tunnel through the sound and soul of so much contemporary music. The difference is that these musty crawlspaces feel groovier and grittier than today's ersatz sounds.

The magic of ghostcapital lies in its juxtaposition of the old and the new, the unknown and known, challenging listeners to expand their own musical comfort zones and perhaps draw some connections—musical, emotional, or otherwise—between seemingly divergent styles. This is especially true of the bizarrely sublime mix tapes ghostcapital curates, either solo or with the likes of Holy Warbles and Aquarium Drunkard. You might not dig all the obscure shit ghostcapital & co. unearth for these collections, but you’ll be taken through a genre-bending kaleidoscope that can awaken your senses to new musical realities.

So if you're jonesing for some seventies Norwegian folk jazz, smooth Ethiopian soul, vintage German punk and wave, Korean downer-folk, early electronic music (from the fifties!), or the folk sounds of a Paraguayan string band, ghostcapital can help fulfill some of your esoteric musical fantasies—and perhaps lead to some new ones.

(Photo: ghostcapital)

In a better world, a lot of things would be true: I'd have a fleet of Dodge Vipers (like my 7th grade history teacher said I'd have because of my test scores), my tweets would get turned into searing movies starring Forrest Whitaker as a dyspeptic writer, and we would be eight games into the NBA regular season.

What a sad, cruel world it is.

Read More

White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race has something for everyone who's set his or her alienation to the accompaniment of screaming. I skipped straight to its excerpt of an 1983 Maximumrocknroll interview with Ian MacKaye, whose pre-Fugazi band Minor Threat had recently released the scene-shaking, name-says-it-all song "Guilty of Being White." And I was instantly reminded of someone who otherwise couldn...

Read More

After a 14-year hiatus, Beavis and Butt-Head has returned to MTV. Many fans of the “new” Beavis and Butt-Head are likely in their mid-thirties to early forties and are enjoying a bit of nostalgia from their high school and college years, when the show provided an easy excuse to do bong hits and invent drinking games (“Okay, every time Beavis says ‘Cool’ or ‘Dumbass’ or Butt-Head laughs you gotta fuckin’ drink”). Glory days. Now a new and younger generation can be indoctrinated to this infectious idiocy.

After watching several of the new episodes—sans bong & drinking games, but with a bottle of wine—I found myself wondering, Why? Yes, I still laughed my ass off. Yes, it was clever to include Beavis’ and Butt-Head’s commentaries on MTV reality shows (Jersey Shore, 16 and Pregnant, Teen Mom) in addition to music videos. But why is the show back? Why do we watch it? And what the hell does it say about us?

Knowing there probably isn’t some grand narrative answer to these questions (nor should there be), I came up with some existential qualities that characterize Beavis and Butt-Head—embarrassing, inappropriate values that make the show such a guilty pleasure.

Unfettered pleasure-seeking ids: Sex-obsessed, immature, unreflexive, irrational perverts. They never end up having sex, but their sole mission in life is to look at porn and try to score. Dr. Freud would be proud. “Hey Beavis, we need a chick that doesn't suck. No, wait a minute, that's not what I mean.” An ontology of primitive pleasure.

Naïve nihilists & myopic cynics: They truly don’t give a shit and are champions of schadenfreude. The world is nothing beyond whatever is directly in front of them. Everything else sucks. And they constantly beat the crap out of each other and destroy or burn whatever they find. “Damn it, all this wussy crap is pissing me off! C'mon, get violent! I wanna see some violence!” An ontology of nothingness.

Champions of sloth: Laziness rules, work is for losers, and their torn sofa is the center of their universe. “This sucks more than anything that's ever sucked before. We must find this butt-hole that took our TV.” An ontology of stasis.

Masterminds of ineptitude: All of their plans result in remarkable failure—and typically self-inflicted pain. “Dammit Beavis, what the hell are you doing? You're not supposed to have your penis out while you're cooking!” An ontology of masochism.

Beavis and Butt-Head is both a mocking condemnation and an exalting celebration of modern American adolescent stupidity. Immune to any type of moral reasoning, Beavis and Butt-Head offer glimpses into what the complete suspension of the ethical might look like. And rather than turn away in fear we tune in and laugh until we piss ourselves. But just a little bit.

Photo: Screen Junkies

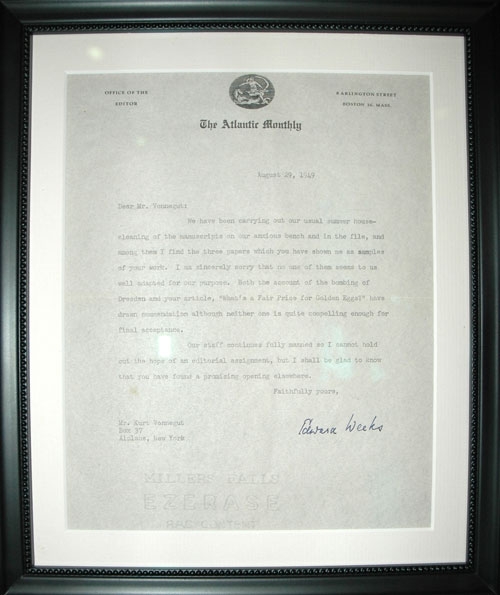

Flavorwire dug up an eleven year-old Missouri Review article on rejection letters from the Knopf archives to bring the Internets a fascinating sampling of some of the "harshest" letters ever doled out to some of the most famous writers of the 20th century. Nabokov, Vonnegut, Stein: talk to the proverbial hand.

Read More

Reading reviews of Stephen King’s new novel 11/22/63, which dropped last week, has left me utterly depleted. There's simply too much to respond to: the issue of how King handles the JFK assassination; his approach to an imagined, altered history; the complications and already worn expectations of time travel. Rumor has it that Oswald is peripheral to the book’s concerns, but how does King get away with utilizing issues so already bloated with use? How does he keep them ripe and alive?

And what’s this review in the New York Times? Are they slumming it, or have they finally acknowledged that King’s contributions should not be relegated to the genre pile? Has the Times taken the current genre debate a step further toward obliterating literary categorization altogether?

I miss The Shining. I miss It. Needful Things was a glorious occasion to be in the darkness. Back then it was just me and the good fear. I don’t like all this history and reference mucking up my faith in the frightening.

It was, surprisingly, the promo page on King’s website that hushed all the other noise enough to spark a true interest. (The interactive Simon & Schuster promos are nice, too.) What caught me was the phrase “a life that transgresses all the normal rules of time.” I’m not normally the betting kind, but I bet you a dollar that when King deals with all this transgression-of-time stuff, he’s also talking about writing. About living as a writer and being on the page without boundaries, without the considerations and demands of life’s biggest trap. His time-travelling protagonist can do anything: King can do anything.

That might be the book’s biggest allure. That, and the consequence: the sweet, frightening certainty King will make us pay for these freedoms.

Photo: AP

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©