Edvard Munch's existential icon The Scream shattered auction records several nights ago. After months of buildup and a televised diss by New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz, The Scream's 1895 pastel (the sole version of four not owned by a museum) sold at Sotheby's for $120 million. Guests posited whether or not it will be headed to Qatar. Me, I wondered if I'd ever see it in person.

I have complicated feelings toward owning art. I “get” that galleries show sellable commodities, a few of which may enter a museum's permanent collection. Most disappear to private collectors, until they return to the auction block or the unpredictable exhibition loan. And I'm not the type who entertains many invitations to visit these collectors' homes, if you know what I'm saying.

Nor am I immune to art-lust. I discovered, waffled about, and ultimately missed my first chance at ownable art in the two-artist show “Finders Keepers, Losers Weepers” at Jonathan LeVine Gallery. I was infatuated withJonathan Viner's ennui-immersed canvas The Fluidity of Power, and for like two minutes I had a shot at it. Stymied both by the price and the thought of fitting the huge thing in my tiny studio, I capitulated. I'm still kicking myself.

I am reminded of one of literature's most scene-stealing artworks: Hans Holbein the Younger's hauntingly skinny painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. It captivated Fyodor Dostoevsky and is a mortal catalyst in The Idiot, where the plot shifts from rosy-glassed Prince Myshkin laughing with the cute Yepanchin girls to tormented Rogozhin musing about putting a knife in somebody. By positioning a copy of this grotesque masterpiece in Rogozhin's flat, the characters effectively splinter into darker realms. Who knows how it would've gone down if they encountered Holbein in Kunstmuseum Basel, where Dostoevsky saw it in 1867 and where it permanently hangs?

I'm mulling another mood-maker: Fix Me Doll by Tokyo-based artist Trevor Brown. It's a 180 from Holbein but right up my aesthetic alley. I've been a fan of Brown's subversive style for years and wear several tattoos inspired by his work. Fix Me Doll was in Brown's latest show in Ginza, Tokyo's Span Art Gallery, and the clock is ticking before another hardcore fan snags it.

Totally more attainable than The Scream, and perhaps more fun to look at? Ah, I'll probably wuss out.

Images: The Scream courtesy Reuters; Fix Me Doll courtesy Span Art Gallery

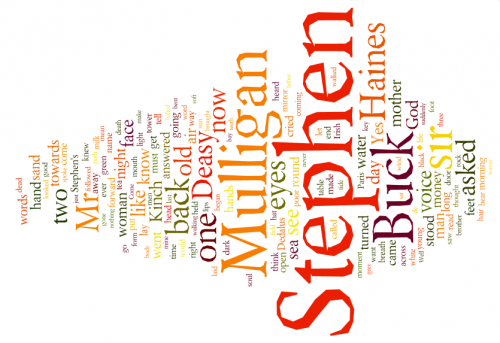

Now that James Joyce's literary corpus is finally in the public doman, I've decided to appropriate it in a singularly 21st-century manner: by readingUlysses chapter by chapter in Wordle, which creates cloud-like infographics based on how often individual words recur in a given text. Visual concordances, more or less.

Each chapter of Ulysses is remarkably different—scholars have noted that chapter breaks serve to shift from one style to another, rather than from one pivotal moment to the next—so I loaded each one into Wordle, let it remove the most common and pedestrian words, and screen-grabbed the results. Here are a few stray observations on the first three chapters, in which Stephen Daedalus's world is fleshed out before Leopold Bloom's arrival.

Chapter 1: Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus (nicknamed Kinch) is talking to his roommate Buck Mulligan in the Martello tower they're both sharing. "God" is mentioned just as often as "mother." The sea and water crop up plenty; the tower is out by the shore, after all. "Mirror" is another popular one, starting with the first line: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed." But it's surprisingly renamed in one of Stephen's most famous aphorisms: "It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked looking-glass of a servant."

Chapter 2: Nestor

I've rearranged the words here to keep "Stephen" separate from everything else, since this chapter focuses on Stephen's job teaching, as well as his uncomfortable relationship with the elder Mr. Deasy. There is a great deal of authority and deference in the classroom and in the office: "yes," "sir," and the verbal conjugations of asking and knowing and crying and answering. The word "history" is hidden but memorable here, just as important as books and, ironically, even more recurrent than God: "For them too history was a tale like any other too often heard"; "All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God"; (best of all) "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Chapter 3: Proteus

Stephen's name is all but swallowed up in this chapter, which ditches its protagonist for the "ineluctable modality of the visible." Instead of names, there are his eyes and the sand, everything to see beneath his feet and behind his back. Of all the German words, "nebeneinander" (n:coexistence; adj: in parallel) is the only one frequent enough to appear here. "God" is again recurrent, but not nearly as much as "Paris" or "woman." Everything here boils down to immediate perception and thought, from the concrete elements of the sea and the shore to the clearly abstract mental verbalizations of that which is ineluctable.

I've already read Ulysses once, in an eight-day marathon as a bet with my friends, and while I enjoyed the shifts in perspective the first time around, I wouldn't have thought that the words would mark it out so clearly. I also hadn't thought about Ulysses in religious terms, so seeing the relative prominence of the word "God" in each chapter tells a story I hadn't noticed before.

Cool stuff. If nothing else, with word-clusters like "God Like Mother," "Look Back Sargent," "Eyes Going Kiss," this thing's a band-name factory.

Flavorpill’s list of cryptic book titles—including the just released HHhH, which got my bloggin' buddy James all infranovelistic, and last year’s C—brought to mind the Diagram Prize, which is awarded yearly to books with the strangest titles. Sometimes the quirk isn’t just contorted syntax or the result of concision; sometimes it's more about semantic friction, when a literal meaning scrapes up against your capacity to make sense. Like last year’s Diagram winner: Cooking with Poo. (Just in case you wondered, Poo ain’t shit.)

Presumably the publisher hoped to cash in on our confusion. After all, titles have to pop. And publishers serve two masters: commerce andcreativity, profit and art. Titles have to be memorable enough to stick with readers, yet clever enough to intrigue tastemakers. No easy task. Try too hard and you end up with something like House of Leaves. Do you get it? The house is really the book, cuz pages can be called leaves! Oh man, so clever! That one, at least to my ears, is a little too proud of its punning. Yet here I am, discussing it.

Others titles have impressed me more. Here's a list of some of my favorites, and what I think makes them work.

- The Crying of Lot 49. Thomas Pynchon’s slightly paranoid novella has stuck in my brain since I first glimpsed its title. It must be that howling gerund with its long i sound and suggestions of pain. And then there’s the title’s sonorous quality. It begs to be spoken aloud. Try it a couple times. Really.

- Euonia. Okay, basically this title banks on obscurity. You probably hadn’t heard the word “euonia” before you heard about this book. It means “beautiful thinking.” It’s also the shortest word in English that contains all the vowels, which makes it a particularly fitting title for Christian Bök’s exercise in constrained writing. Each of the book’s five chapters uses only one vowel, beginning with a, ending with u. The book is a striking thing to read, especially the guttural u chapter.

- Life A User’s Manual. The intricate phenomenological descriptions that George Perec composed for this book—each chapter describing a single room in the apartment building where the protagonist, a recently deceased guy who liked jigsaw puzzles, lived—aren’t exactly what you’d expect to find in a typical user’s manual, but this is life, not a screwdriver. The title sticks with you because most novelists (not to mention most publishers) don’t have the nerve to put a technical sounding title on their novels; such a thing might dissuade impulse buyers.

- Watership Down. Amazing use of ambiguity here: you don’t really think of Watership Down, the hill, when you first read it. Instead, you picture a curious seafaring vessel, "down" as in sunk or in the process of going down. Then you read about rabbits and "hrair limits" and it all begins to make a bit more sense. But at that point, you’ve already been led down the garden path, and the title is ensconced in your memory.

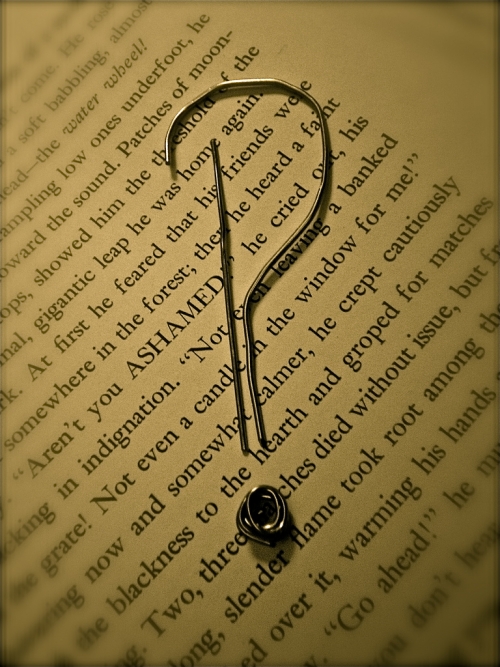

Those titles are solid enough to serve both art and commerce, I think. Of course, I doubt they’re as brilliant as my idea for a novel concerning self-motivating punctuation marks. The title's not gonna be written out but set with the interrobang glyph. I'll let the critics argue about how to pronounce it. And yeah, the gimmick is that the narrator's deployment of punctuation marks evolves as her narrative unwinds. it'll be nigh unreadable, but oh so punny and witty. Beat that, internets.

Image: flickr user GardenofEdits

Last weekend, The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery held a three-day conference in Washington D.C. to “review, discuss and debate” the research that has been and will be done to recover Amelia Earhart’s ill-fated Lockheed Electra Aircraft. On the island where she is believed to have died, glass fragments bearing a resemblance to a 1930 freckle-treatment jar have been discovered. As summer approaches, the good doctors at Scientific American will help us keep our skin spot free, but beware the devil…he leaves his footprint on desert isles for reasons subtle and inscrutable.

1. “When reassembled, the glass fragments make up a nearly complete jar identical to the ones used by Dr. C.H. Berry’s Freckle Ointment. The ointment was marketed in the early 20th century as a concoction guaranteed to make freckles fade. ‘It’s well documented that Amelia had freckles and disliked having them,’ [said] Joe Cerniglia, the TIGHAR researcher who spotted the freckle ointment as a possible match.”

— Rosella Lorenzi, “Earhart’s Anti-Freckle Cream Jar Possibly Found,” Discovery News, 30 May, 2012.

2. “At this time of year there are few questions which are more frequently addressed to the ‘family chemist’ and fewer still to which he ordinarily gives so unsatisfactory a reply as, ‘What shall I do to cure my freckles?’ Knowing as we do how greatly the popularity—i.e. the business prosperity—of the majority of our friends depends upon the votes and interest of their lady customers, we have been at some pains to lay before them such an amount of practical information upon the above subject as will enable them to retain the good will and material gratitude of their fair interrogators, on the one hand, and to put a little extra profit in their hands, on the other.”

—B. & C. Druggist, “The Treatment of Freckles, Moles, Etc.” Scientific American Supplement no. 507, 19 September 1885.

3. “What marks were there of any other footsteps? And how was it possible a man should come there? But then to think that Satan should take human shape upon him in such a place where there could be no manner of occasion for it, but to leave the print of his foot behind him, and that even for no purpose too, for he could not be sure I should see it…I considered that the Devil might have found out abundant other ways to have terrified me than this of the single print of a foot.”

— Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe, 1719.

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the gaslight, candlelight, torch, or starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The citational constellations work to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” They are offered with astonishment and largely without comment. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

Image: cosmeticsandskin.com

In Granta, Jaspreet Singh recently described how her mother, in translating the daughter’s book from English to Punjabi, “preserved the emotional impact” of the fourteen stories she had written, up until the final piece, which read very differently.

My mother translated the story I never wrote...This new fourteenth story was my mother’s story and not mine. No translator, no one has a right to change my story, I thought. Not even my mother.

It is a strange and unsettling thought that a translator might deliberately or, worse, unconsciously present us with a story only tangentially related to the original-language text. But what, exactly, do we feel if we realize that we've read a false or unfaithful translation? Loss? Rage? What exactly have we lost, if we cannot read the original, and where should we direct our anger, if we have been given something that otherwise we would not have had at all?

Translation is the last remaining vestige of rewriting; it is a career not unlike that of being a scribe in medieval times or a typist in the twentieth century. “There’s nothing glamorous about it,” my friend said of working as a translator at UNESCO in Paris. “I switch the words from French to English, make sure it sounds logical, and then pass it on to my reviser.”

Readers (and even editors!) often assume that a fluid translation is accurate, and reviewers consistently declare English-language books from abroad "ably translated," without much thought given to the underlying process. Even when the translation is read and annotated by the publisher, questions about the text are usually posed to the translator, rather than being answered by looking at the original. So rogue translations are all the more discomfiting when their dissemblances are discovered.

If the rewriting Jaspreet Singh’s mother performed feels like theft, then where do you draw the line between transducing something and traducing it? Are all translators thieves?

I detest the Italian adage “traduttore, traditore” ("translator, traitor" would be the most literal rendering). There is something available now in the target language whereas previously there had been nothing. That is no betrayal; indeed, it’s a gift. Sometimes the translation is for the better, as when writers like Paul Auster find themselves more famous abroad than at home. Really, attempting to moralize this recalls the recent (and inconclusive) brouhaha over facts and truth in John D’Agata and Jim Fingal’s The Lifespan of a Fact.

I don’t think a question so polarizing can be answered, and the futility of the thought itself only merits satire—as in this piece from Dezső Kosztolányi’s Kornél Esti, translated by Bernard Adams, about a kleptomaniac translator:

In the course of translation our misguided colleague had, illegally and improperly, appropriated from the English text £1,579,251, together with 177 gold rings, 947 pearl necklaces, 181 pocket watches, 309 earrings, and 435 suitcases...Where did he put these chattels and real estate, which, after all, existed only on paper, in the realm of the imagination, and what was his purpose in stealing them?

image credit: Igor Kopelnitsky, corbisimages.com

HHhH, Laurent Binet's account of the assassination of a top-ranking Nazi in 1942, is divided into 257 mini-chapters. In an attempt to comprehend Binet's layering of fact and fiction, as well as the totally incomprehensible era he describes, I'm going to try out his "infranovel" techniques myself.

Read More

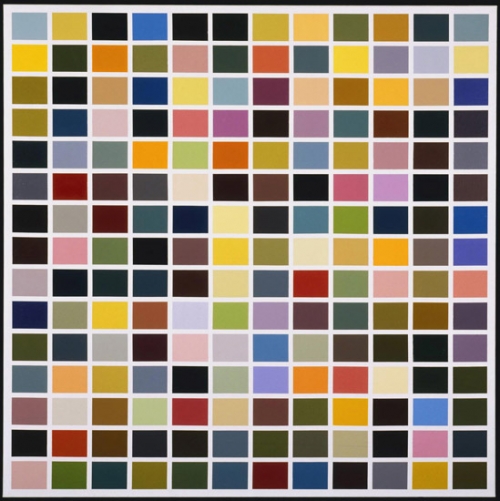

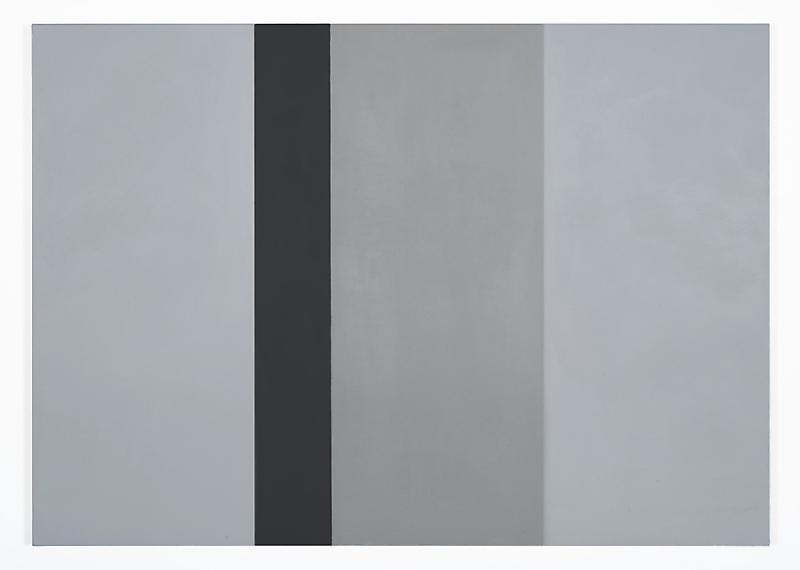

I find The Paris Review's literary paint chips feature—“paint samples, suitable for the home, sourced from colors in literature”—totally sublime. Their 28 choices, including the requisite Fitzgerald (“Dock Green") and Hemingway (“Elephant Hills”), suggest Gerhard Richter's color-chart paintings: systematic permutations of chromatic variety, as mundane as industrial paint samples yet as thrilling as exploring every possibility of hue and tone.

Okay fine, I'm also an art nerd. So the literary paint chips got me thinking: what happens when you locate these colors in real abstract art?

Think of the possibilities not covered here! Those high-altitude sunsets in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain, or Füsun's tear-reddened eyes in Orhan Pamuk's The Museum of Innocence. The “dead channel” sky of William Gibson's cyberpunk classic Neuromancer could be a flickery gray-green...if, thanks to Gibson's now-retro vocabulary, we can remember what “screen snow” even looks like.

Images: Gerhard Richter courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art; Brice Marden courtesy Wikipedia; Agnes Martin courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York; Mark Rothko courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Byron Kim courtesy James Cohan Gallery

Forget what Kayla B. wrote about book trailers. (You kiss your mother with that mouth, Kayla?) Check out the new promo for our spring title, Louise: Amended, and find out why our March theme is "Demon Wrestlers." Happy viewing!

Read More

“I WANT A PSEUDONYM.”

I looked at my friend like he was saying he wanted manicured eyebrows.

“Come again?” I asked.

“You heard me. I don’t want to use my real name.”

“Sure, but a pseudonym? Why not just get it legally changed?”

“I don’t need to get a new driver’s license. I just don’t want my name on the manuscript.”

“Look at me. You’re cool. You’re brilliant. Your name is awesome. “

“It’s not about what I like or don’t like. Did you see that one HTMLGiant post? Sylvia Plath went as Victoria Lucas in the first editions of The Bell Jar. There's a whole book on pseudonyms." He poured himself a shot of Cutty Sark. “I like my real name just fine. But I don’t want an editor googling my name when she or he picks it up.”

I sighed. “Okay, fine. But you’ll get it published with your real name?”

“Sure, if you say so. We’ll have to see what the marketing people say. They got Jo Rowling to call herself J.K. Rowling, and it worked.”

“So what kind of name were you thinking of?”

“I don’t know. Something classy, something aristocratic.”

“Well, F. Scott Fitzgerald is taken. So's Edward St. Aubyn.”

“Wasn’t Evelyn Waugh good?”

“Sure, but why copy him?” I thought for a second. “Hey, I knew this guy named Cambrian.”

He snorted. “Cambrian? The geologic era?”

“Hey, you wanted sophisticated. You can’t do better than Latin. Throw on a double-barreled name, and you’ll fit right in at the Crillon Ball.”

“Okay. So I could be Cambrian Williams-Burke.” He emptied his glass. I poured him another.

“I think you should be a bit more honest, though. You’re from the South. Say you’re from the South.”

“I could do that. If I want to say I’m like Breece D’J Pancake or that Confederacy of Dunces guy, I’ll just find myself a hillybilly name. Clayton Rambler. Colt McCoy!”

“That’s a cheap joke,” I said as I poured myself some Cutty as well. “You can do better than that. Come on, make it an honest pseudonym. Just use your pet and street name and make a Porn Star name.”

“I never had a pet, though. I’ll make my first name Wythe.”

“I like first names as last names. James, Ryan, Kirby...”

“Kirby. Wythe Kirby. That works.”

I smirked. “Hey, that rhymes with your real name. See, I told you your real name was good enough.”

“Nah, man. ‘Wythe Kirby’ doesn’t pull anything real up on Google. I’m using it.”

“Great. Does that mean you’re ready to start writing your book now?”

image: vice.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©