In honor of his birthday (June 25), Brainpickings related George Orwell’s top four motivations for writing: egoism, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, and political purpose. I have often thought that pinning down why I write might give me insight into how I could proceed with new creative work, so I was quick to connect Orwell's motivations with my own. In my twenties I was big on getting things right, creating vivid moments of some sort of true experience, kind of like Orwell's historical impulse. More recently, the sound and impact of words—pure aesthetics—have come to the forefront.

What intrigues me now is Orwell’s attention to early development and inescapable "emotional attitude." This is from his essay "Why I Write":

I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in—at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own—but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, in some perverse mood; but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write.

For me, this relates to Ben Marcus’ theory that each writer has one essential story to tell — a story that must be repeated in different ways and can never be resolved. The thought that the compulsion to write can be understood as some kind of unresolvable psychological tic ... tickles me. There is something wrong with writers, and we've made it our business to publicly pick at our scabs.

It’s interesting to compare Orwell’s insistence on early influences with Joan Didion, who has a "Why I Write" of her own. Didion says, “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write. I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.”

With Didion, I find the answer to the question of how to proceed. While I very much enjoy thinking about early influences and uncontrollable compulsions—and I love Orwell for saying "Good prose is like a windowpane"—I really don’t have a hold on why I write until after I am writing. The compulsion to write in itself is only really examined, for me, in the process of writing. I don't have any real ideas about what my scabs might look like until the writing itself shows me. It may be my poor memory, but I need the physical presence of words to spark any kind of recognition of that which is real.

In any case, thinking about writing never quite gets any work done. The only thing is to keep writing.

image: bambinipronto.com.au

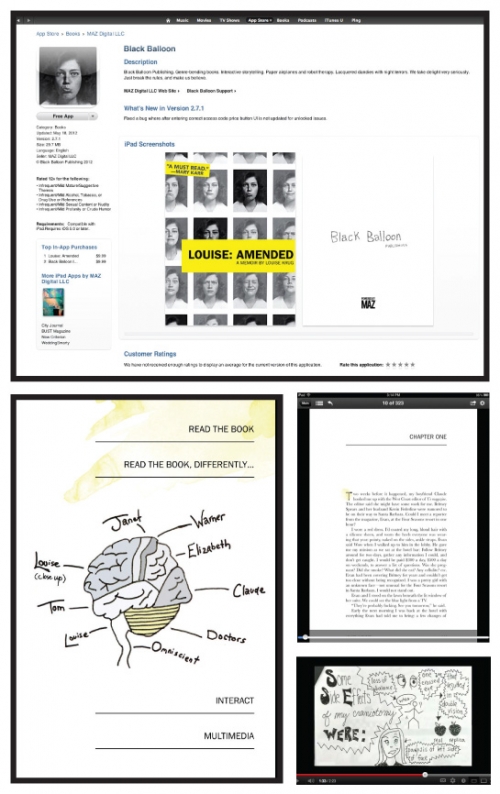

Here at Black Balloon, we like pushing the boundaries of what a book can be. We think our evolving e-book for Louise Krug's new memoir, Louise: Amended, does just that, so we're very excited to share it with you—so excited that, for the next two weeks, we're giving it away as a free iPad download! But wait—there's more!

Read More

Have an epic day, and be safe out there. We'll be back on Monday with a big announcement (hint: giveaway).

Read More

I'm on self-imposed True Blood exile. Return readers might already know that I much prefer this vampire world. But the Deep South bloodsuckers just threw me a major hook: Iggy Pop and Best Coast's Bethany Cosentino teamed up for a song to be featured on True Blood's July 8 episode.

Punk's gnarliest godfather crooning it out with a tattooed surfer chick nearly four decades his junior? Music to my ears. Cosentino banishes much of her freshman haze for bluesy lyricism on Best Coast's latest album, The Only Place, while ol' Iggy balances his Stooges standards with French jazz (Préliminaires). His softer side and her robust vox could equal an awesome jam. I'm tuning in.

Historical evidence supports such cross-generational crossovers. Consider Loretta Lynn's award-winning comeback Van Lear Rose, produced and co-written by Jack White. Taking it back further: Nat King Cole's “Unforgettable,” remixed as an imagined—destined, really—duet with daughter Natalie, which won multiple Grammies.

But thoughtful musical match-ups need not rely on interactive technology or sexy vampires. Here's several I think would rock out:

Marilyn Manson and Zola Jesus

Anybody remember 1997's Spawn soundtrack, a well-intended if obtuse blend of popular rockers and trendy electronica? Its sole single found the goth demigod dominating trip-hoppers Sneaker Pimps. Pair Manson with pint-sized Zola, though, and she'll unleash the operatic angels of heaven, hell, wherever onto the Antichrist Superstar's pallid ass.

Björk and tUnE-yArDs' Merrill Garbus

Uh, obvs? Even if we overlook the vocal elasticities of these two, consider Björk's instrumental minimalism on Vespertine and Medúlla, plus Volta's added horn flava. Pair with Garbus' looped percussion and Whokill's sax riffs, and we just made some serious “Bizness” up in here.

D'Angelo and Frank Ocean

The swaggering Soulquarian D'Angelo ends his sabbatical with a long GQ interview—his first since 2000—a Bonnaroo SuperJam with ?uestlove, and more to come. Meanwhile, R&B wunderkind Frank Ocean readies his major-label debut Channel Orange, more a soul-music tutorial than typical pop drivel. If D'Angelo channelled quiet-stormer Smokey Robinson on “Cruisin',” then young Ocean, who has written for John Legend and Beyoncé, is more than ready to make his own neo-soul waves.

Lou Reed and Lana del Rey

Within Reed's lauded back catalogue, I particularly dig his circa-Velvet Underground rasp against Nico's torchy croon. Enter del Rey, the “self-styled gangsta Nancy Sinatra” (quotes The Guardian), woozy balm to Reed's yowl. For the del Rey naysayers: consider Madeline Follin, the hippie-chic songbird of NYC noise-poppers Cults. Follin's self-lacerating delivery more than matches Reed's solo work. She could do wonders covering The Bells.

Massive Attack and Jessie Ware

The trip-hop progenitors bear a nonpareil CV of guest vocalists for their somber soundscapes, including Shara Nelson (“Unfinished Sympathy”), Tracey Thorn (“Protection”), Elizabeth Fraser (“Teardrop”), and Sinéad O'Connor (“Special Cases”). I recommend adding English singer-songwriter phenom Jessie Ware to that lineup. Her sometimes-slinking, sometimes-searing delivery echoes Martina Topley-Bird (precocious veteran of the Bristol scene, singing with Tricky when she was still a teen). I've got my ears attuned to August 20, when Ware's debut Devotion drops.

Images: Iggy Pop + Best Coast: Pitchfork (slightly photo-chopped by author); Jack White and Loretta Lynn: Buzznet; Marilyn Manson:Devangelical + Zola Jesus: Facebook; Björk: Rubyfruit Radio + tUne-yArDs:The Oedipus Project; D'Angelo: GQ + Frank Ocean: Consequence of Sound; Lana del Rey: Berlin Hair Baby + Lou Reed: ROKPOOL + Madeline Follin: Impose Magazine; Massive Attack: Greenobles + Jessie Ware:Pitchfork

I've been writing about language usage for the last two weeks, spurred on by Steven Pinker's critique of a New Yorker piece on the divide between prescriptivists and descriptivists. Last week, I argued that patterns of speech are not just abstract tools; they actually constitute part of our bodily identity, which complicates claims about what constitutes good speech. This post looks at how we can still probe language and give it some measure, even if the tools we have are as culturally particular as Samuel Clemens's psuedonym.

How you speak lets the world know who you are. Even if you switch accents as often as this kid, you reveal your origins with the idioms you use. You could be a non-native speaker, a b-school d-bag, a busted urbanite, a grifter whose slithering turns of phrase endear you to anyone with a susceptible ear. However you speak, we have the sense, egalitarian-minded that we are, that it is illiberal to judge you for idiosyncrasies outside your control—your place of birth, your heritage, your parents’ linguistic tics.

This is why language standards are such difficult pancakes.

Yet, there is the problem of taste. Sometimes you have to wonder why certain gestures really hit you in the gut but glance right off other people. There's no single metric of taste, but thankfully there’s something better: understanding the process through which aesthetic judgments are affirmed or disavowed. You can account for taste, even if it involves complex exchange rates.

Here's how it works. Taste is at once an inversion and a strengthening, a way of self-reflectively relating your own appreciation of a thing to that of others—specifically, the peers whose opinion you wish to garner, passively or not. So when you're looking at a piece of art, you gague your own reaction to it and simultaneously measure that feeling against that of the people to whom you'd like to appeal—in both senses: you want your judgment to be appealing to them, and you appeal for their support in having made it. In doing so, you're providing judgments about things that other people use to inform their own tastes. Sort of like dumping a bucket of sand onto the beach on which we're all making mud castles: it's good to have dirty hands.

Once you realize that taste is endlessly being reshaped through the intentional effort of many people, yourself included, you're all set to take on prigs and pedants. Suddenly, their bugbears are mere historical contingencies. "That" and "which," for instance: someone at some point assured us yanks that these were distinct, even though the record of written and spoken American English upholds no distinction. Count it another quixotic case of prickly genteel folk attempting to swim against the linguistic tide.

Speaking of "quixotic," consider a cherished old volume of mine, Fowler's Modern English Usage. The second edition, printed in 1965, calls out people who pronounce Quixote as it would have been pronounced in Spanish for "didacticism." Now, a mere half-century later, people who don’t give a Spanish pronunciation to Cervantes’ character would almost certainly stand out as unschooled.

Other manuals fare poorer. Strunk and White's The Elements of Style wears its convictions on its spine: here is a unified manual of stylistic concerns, rendered in their simplest components. Unfortunately, the book itself is riddled with tips and tics that are just plain wrong.

Garner's Modern American Usage values communication over avoidance, and even helps people know exactly how out of touch their grammatical foibles are. While verging on the pedantic, it has no pretensions about preserving an ahistorical version of language. For words like "enormity,"famously misused (or was it?) by President Obama, Garner’s includes a scale laying out how acceptable the usage error is. You can feel safe indulging your peevological urges if something has low broad acceptance, but once something is as gone as the distinction between nauseous and nauseated, you better let it go.

Usage guides, and the people who love them, have got to take into account the way language evolves. After all, we just want to communicate as clearly and effectively as possible—which means in full awareness of the way language is made on all of our tongues. Hopefully, we can agree on that.

Jay McInerney, writing in the Guardian last month, tried to understand the enduring power of The Great Gatsby. His answer was writerly: it's the prose, stupid. "Without Fitzgerald's poetry," McInerney says, "without the editorial consciousness of Fitzgerald's narrator Nick Carraway, the story can seem threadbare and melodramatic."

Read More

New rules for fulfilling your creative dreams: 1) work when you're tired; 2) work when you're buzzed; 3) forget everything you learned in school.

Read MoreIf you're too lasy for even Wikipedia or Spark Notes, here's a big ol' list of spoilers to save you some time.

But before you start spouting off those endings, maybe you should check out the copyright laws behind the books first.

Or maybe you're better off keeping quiet, staying holed up in your luxurious Cobble Hill brownstone.

Maybe keep your thoughts in your Moleskine, and raise its value that way.

Just make sure your grammar is up to par, lest you be mistaken for a poorly worded email spammer.

And who knows? Your work could end up winning you the Kyoto Prize, and you won't know what to do with all that prize money.

Last week, I mused on Steven Pinker's critique of a New Yorker article on descriptivist and prescriptivist ways of thinking about language. Pinker came out swinging against that simplistic dichotomy, which is fine and dandy, but I had some qualms with his take on "standard English" (to wit: comparing the tacit rules of language to traffic patterns is a category mistake). Today, I want to talk about how we talk, and what that says about us.

People are brought up within a specific cultural environment, taking its imprint into their bodies—where you're from and how you come to know yourself wires your brain—and enacting its common codes as their habits, trains of thought, manners of speaking. These things, among them tacit rules of language, are in a real sense enfolded, engraved into the flesh. To say that a person ought to talk according to a standard that is not their own is far more alienating than telling them, for instance, to use the metric system. It is to say that those of us who didn't come from the right milieu must remake our sense of and capacity for self-fashioning. We must become what we were not, in terms we would not use.

At least, if we want to prosper ’round here.

Anybody who’s struggled to disentangle all the likes knotted into their speech after a California childhood knows how difficult it is to remove a single word, much less syntactical patterns. Besides, they are intimate indications of a person’s background: the lingering y’alls in a former southerner's worn-through drawl indicates to anyone with an ear for it where they’re from. To recognize dialect and accents—to appreciate the pompous way the guy your friend is dating always uses shall instead of will—is to recognize a linguistic territory, geographic or socioeconomic or affinitive or otherwise. And the range and variation of each contributes to the overall richness of language as a whole: each differentiation swells the sense of words and the ways they signify.

Still, there’s something compelling about the notion of a “standard English.” This shouldn’t be convincing on the face of it. What’s gained if we all converse or write precisely alike, noting with obsessive care the pedantries of long-dead, only ever partial, savants? What’ll we lose if we don’t?

Language lives and floats on the breath of those who speak it. It is continually being remade as it is exhaled from humid, living lungs, and, being caught up with the formative experiences of speakers’ identities, it comes to reflect the broader trajectory of the mouths that speak it. A lot of the shrillest warnings about language usage faltering merely indicate a shift in dominant trends, even if those issuing them would tie that shift to a decline in civilization. And disparaging specific patterns of speech as uneducated, ill-suited for high paying work, or essentially different—when in fact the only difference they signify is the history of the person that would say them—is lame. There is nothing, as Pinker says, inherently wrong about one manner of speechifying, so long as it makes sense. (Fine, this is notalways the case; more on that next week.)

What does this leave those of us who’ve grown fond of our Fowler, our elementary styles, our usage manuals, who are invested in aesthetics, in really getting down to the right stylings of linguistic awesome? It leaves us the flow of language use, past senses coursing toward future ones, and that is a turbulent current. But it is something, if you know how to fathom it. Mark twain, motherfuckers.

Stay tuned for the final installment of this series, coming at you next week.

Image: A Niagara of Alien Beauty

Last week, science writer Jonah Lehrer was all over the news after reporters found a number of substantial repetitions between his previously published writings and his new work for the Frontal Cortex blog he brought with him from Wired to the New Yorker. (And now there's this.) A year-old piece from the Observer quoted Lehrer describing some aspects of his high-paid lecture circuit as “existentially sad,” particularly his surplus of electronic hotel keys. Daisy Buchanan and Søren Kierkegaard know what he means.

1.

“You end up getting existentially sad, where you look through your wallet and you realize you’ve got like seven hotel keys…It happened last week in San Francisco, where I was convinced this key wasn’t working. I went down to the front desk, and they pointed out that I was using the wrong key. It was from a month ago.”

—Jonah Lehrer, quoted in the Observer, 2011.

2.

“And yet it could be that the little I have to say contained some particular remark which, if it met with favour and indulgence, might be found to contain some truth even if it concealed itself under a shabby coat.”

—Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, 1843.

3.

“He took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one, before us, shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel, which lost their folds as they fell and covered the table in many-colored disarray. While we admired he brought more and the soft rich heap mounted higher—shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange, and monograms of Indian blue. Suddenly, with a strained sound, Daisy bent her head into the shirts and began to cry stormily. 'They're such beautiful shirts,' she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. 'It makes me sad because I've never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.'”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 1925.

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the gaslight, candlelight, torch, or starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The citational constellations work to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” They are offered with astonishment and largely without comment. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

Image: keanureeves.blogspot.com

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©