I first came across Enrique Vila-Matas, whose book Dublinesque drops stateside today, on a cold snowy morning in the Midwest. School was canceled. Work was canceled. And at the top of my pile of books to read wasn't something by Enrique Vila-Matas. Instead, it was a gorgeous Melville House edition of Bartleby the Scrivener.

My back to the frozen world outside, I paged through the story of a man himself frozen in repeating a perpetual, unalterable phrase: “I would prefer not to.” The idea of a man who had moved beyond logic and reason made me shiver in the heat of the fireplace.

What could I read after a such a chillingly final story? I looked down the pile, and my eyes lit on an unlikely title: Bartleby & Co. As far as I could tell, this was the story of a man who had decided to investigate the "writers of the No." Less a novel and more a disembodied set of footnotes, Bartleby & Co. trawls across the literary landscape of figures who, like Bartleby, have gone silent. I read the narrator's skewed commentary on Salinger, and also on Alfau, Derain, Rimbaud, Celan...

So this was who you could read after being overwhelmed by the morass of Modernity, I thought. I looked at the spine. Enrique Vila-Matas. This was the author who found something new and interesting to say about these fragments we have shored against our ruins. How had none of my friends told me about this wildly popular Spanish author, churning out new books about literary sicknesses? (I couldn't even remember how that book had gotten in my room.) I ordered Montano’s Malady immediately, and then waited eagerly for the English translation of Dublinesque.

Dublinesque doesn’t disappoint. In it, publisher Samuel Riba—“he likes to see himself as the last publisher,” Vila-Matas writes—sets out for Dublin to orchestrate a funeral for the printed book, for great authors and the entire “Gutenberg galaxy.” Literature has no plans to die, of course, so the trip becomes a rather complicated affair.

The story takes place chiefly in Dublin and under the aegis of Joyce’sUlysses, but it’s no surprise when John Huston’s interpretation of “The Dead” is mentioned, or when a man strongly resembling Samuel Beckett appears. Still, the author reminds us that Riba “also took up publishing because he’s always been an impassioned reader.” And as Riba is a recovering alcoholic, it may well be that literature is a different sort of addiction for him. If this hall of mirrors, in which every book Riba (or, for that matter, Vila-Matas) has read is reflected back at the reader, seems overwhelming at first, how much more alluring it must seem to the seasoned reader, who will immediately catch the reference to Paddy Dignam or El Jabato.

No book exists in a vacuum, but Vila-Matas’s books are exceptional in their dependence on all other great books to validate their own existence. For people who (like me) don't have doctoral degrees in the humanities, it's a relief to know that there's a rather enjoyable storyline, and a great deal of wit to boot. Still, I can’t imagine anybody liking Dublinesque without having already read Ulysses and most everything else in the Modernist canon—but after Ulysses, Vila-Matas’s Dublinesque seems like one of the few twenty-first-century books worth reading.

image credit: ndbooks.com

Hotels that emphasize shagging over slumber get a bad rap in the States. Think about it: a dusty gyrating bed, a coin-operated TV chained to the floor, broadcasting 217 flickery channels of porn—plus Animal Planet for the truly deviant. Photographer Misty Keasler (interviewed here in the Morning News) offers a radically different perspective in her series Love Hotels: The Hidden Fantasy Rooms of Japan and the same-named monograph, exposing the West to sanctuaries equal parts shockingly subversive and substantially sexy. In sum: Hello Kitty S&M Room.

As a frequent traveler to Tokyo—and connoisseur of its nightlife—you better believe I know a thing or three about love hotels. Before I file a “Raw Nippon” post on where to get your jollies (or just where to bathe in a couple-sized martini glass), I gotta clarify something. The following list, a cross-section of pop culture, shows that love hotels are more than just destinations for debaucherous denizens (though there's plenty of that).

William Gibson, Idoru

The cyberpunk scribe's 1996 novel, weighing a crystalline Far East against a murky, sodden London, was my gateway to love hotels. Their dual nature—intimacy and isolation—is spelled out in an exchange between young protagonist Chia and her geekish ally Masahiko:

“Private rooms. For sex. Pay by the hour.”

“Oh,” Chia said, as though that explained everything... “Have you been to one of these before?” she asked, and felt herself blush. She hadn't meant it that way.

“No,” he said... “But people who come here sometimes wish to port. There is a reposting service that makes it very hard to trace. Also for phoning, very secure.”

Haruki Murakami, after dark

This taut little 2004 read occurs totally at night, featuring a love hotel as a major plot element: the scene of a violent crime and a retreat for protagonist Mari. As Hotel Alphaville owner Kaoru explains to her, “it's a little sad to spend a night alone in a love ho, but it's great for sleeping. Beds are one thing we've got plenty of.” Nightly rates at love hotels are typically less than those of business hotels, if you're shrewd.

Laurel Nakadate, Love Hotel and Other Stories

Nakadate's career survey Only the Lonely at MoMA PS1 last year included her 2005 single-channel video Love Hotel, featuring the artist slow-grinding on gaudy beds throughout Japan. Though we can imagine the camera as the observer's seeking gaze, simultaneously it is solely Nakadate, awaiting a partner never to appear. “It's about loneliness,” she explained. “About being by yourself in a place where you're supposed to be in love.”

Nobuyoshi Araki and Nan Goldin, Tokyo Love and Photographer HAL,Pinky & Killer DX

Two glossy photography books, the former from '94 and the latter over a decade later, celebrate love hotel patrons as much as the kaleidoscopic environs themselves. In Tokyo Love, Araki, the mad lensman of Japanese eroticism (see Tokyo Lucky Hole) and post-punk documentarian Goldin teamed up to capture indiscriminately youths in love. For HAL (his nom de photo), a mainstay of Golden Gai, Pinky & Killer DX was a close-cropped and super-saturated exposé on Tokyo's lusty after-hours lot. Funny thing is, each time I visit Tokyo I meet several more subjects from HAL's lens.

Images: Photographer HAL Pinky & Killer DX via Photoeye.com; Idoru/after dark collage via Project Cyberpunk and Bull Men's Fiction; Laurel Nakadate via Danziger Projects

Apparently, Colm Toibin's book New Ways to Kill Your Mother, published by Scribner this month, doesn’t provide any instruction on how to actually kill your mother. While this might be a grave disappointment to some, I’m inclined to smirk (with both glee and a bit of friendly mockery) at Toibin’s recommendation to put mom on ice—at least in fiction. Dwight Garner, reviewing the book for the NYTimes, explains: “His essential point, driven home in an essay about all the motherless heroes and heroines in the novels of Henry James and Jane Austen, is that ‘mothers get in the way of fiction; they take up the space that is better filled by indecision, by hope, by the slow growth of a personality.’”

Really, aren’t fiction mothers just a pain in the ass? If a novel has a mother in it, she’s usually too complicated and infuriating to develop in a half-assed way, and so the whole book ends up being about her. She’d just love that, wouldn’t she?

If you're a writer, you’re stuck having to acrobat around a reader’s wondering, “Where is the character’s mother? Does she know what her son’s doing?” every time you want a character to do something bad. Raskolnikov was gonna kill that landlady but then his mom came home. Groan. Guess he’ll never be friends with that prostitute.

Toibin points out that orphans are great characters in fiction, and really, how could they not be? Without all of that guidance, nourishment and guilt-mongering, orphans are free to find their own way in a world devoid of preconceived notions. Plus, devastation and an incurable longing are great ways to secure a far-reaching and easy sympathy from readers. Oh, the poor dear, that’s why this character’s acting up.

Still, I find this proposition of parentless fiction a little weird. Possibly indicative of a handful of bizarre psychological ramifications. Do we have a hard time imagining mothers without pillows clutched in their fists, coming to snuff us out? Do we really think that kids raised in two-parent households are so adjusted as to be boring? Are your parents making it hard for you to develop a personality or experience indecision and hope?

I love a little mom in my fiction. I say the more mothers, the better.

image: bbc.uk.co

Sheila Heti came from Toronto to New York this week, ready to launch her "novel from life" How Should a Person Be? in the States. I’m a fanboy, so of course I was there at the Powerhouse Arena on Tuesday night.

Two weeks ago, I had pushed a copy of the book into my friend’s hands. “You’ll get a kick out of it,” I insisted. A week later, she told me she had a clear picture of the characters: she was positive that the narrator, also named Sheila, was a tall woman with flowing, curly hair—the kind of woman who effortlessly pulls off a feather boa. And Margaux, her best friend (also the book's dedicatee), had to be blonde, with a clean-cut face and an understated, artsy style.

Well, not quite. A quick Google search led to this picture, with Margaux Williamson on the left, and Sheila Heti on the right. Sheila had put a version of herself in How Should a Person Be?, but it wasn’t quite the same as the woman who stood in front of us Tuesday night.

“Yeah, I sort of forgot to describe myself,” she said when we mentioned the discrepancy. Then she looked down and signed my book.

Did it bother her?

“No, I’m not the person I put in the book. That was a different time.”

Hmm. Would Margaux be upset if we asked her to sign the book? (Margaux has not always been the nicest friend.)

“Margaux? She’d love it!”

We went over to Margaux, who was surrounded by an adoring crowd. We opened our books to the dedication page and handed them over. She couldn’t stop smiling as she scribbled our names and her signature.

We couldn’t believe ourselves. It was like seeing the cast of The Hills in the flesh. They were actually real? Wearing the same kind of clothes we did? And signing our books, even though they’d fought about their lives being recorded?

Cool.

••••

A couple of months ago, I’d gone to a different bookstore to see John D’Agata and Jim Fingal talk about their own relationship, recorded in The Lifespan of a Fact. These were two men who had argued over most of the facts in an essay that was later turned into the book About a Mountain.

“Wow, Jim, your penis must be so much bigger than mine,” John D’Agata spouts off sarcastically in one part of the book. “Your job is to fact-check me, Jim, not my subjects.”

As it turns out, quite a bit of this dialogue had been made up. This knowledge didn’t endear me to the idea of meeting a self-absorbed artiste (D’Agata) and a battle-scarred fact-checker (Fingal). These were the characters they’d made out of themselves, after all.

Then the two men walked to the front of the room.

John D’Agata is actually extremely nice, even apologetic—one minute ofthis video shows how transparent his emotions are. I was astonished at the vehemence of my fellow audience members. “Can’t you understand that you shouldn’t present distorted facts as journalism?” they asked.

No, John D’Agata explained in an apologetic way, he wasn’t writing journalism. An essay was a completely different thing.

He seemed surprised at the monstrous caricature he’d created of himself. Jim Fingal found the whole setup rather amusing. I looked around nervously for tomatoes about to be thrown. These two writers had become victims of their own inventions.

••••

Did either pair of authors owe it to their readers to present an accurate picture of themselves? What transformation was permissible in art, if these books were supposed to be “nonfiction” or “a novel from life”? Was I right or wrong to be surprised by the people behind the characters?

I had read about these characters, but seeing the authors left me wondering: How should a person be?

image credits: velvetroper.com; torontoist.com

In preparation for the weekend, prepare for some drunk texts from your favorite literary rockstars.

Just don't overanalyze them to a Louie CK-esque point of smart-dumb self-hatred.

Besides, why are you texting when you can be using a typewriter instead?

Or better yet, write your next novel on a roll of two-ply Charmin ultra.

If anything, it will add to your legend, should you decide to pull the ultimate literary hoax.

Just make sure you don't end up in a Japanese love hotel with the press following you.

Otherwise, you'll end up back home, living with your parents and sleeping in your childhood bedroom.

And how are you going to explain that to your kids?

Image credit:

Boozing is an awesome anytime activity in Tokyo. 7-Eleven tallboys and your average bar's draft run hundreds of yen cheaper than a cappuccino, and since trains stop running at midnight, nearly all watering holes remain open and packed until dawn. But to cultivate that Cheers-like vibe, in a joint a tenth of the size but with 10,000 times the character...that takes some effort. I spend my time in Golden Gai, a network of narrow alleys whose collective footprint approximates Tompkins Square Park, yet is filled with some 200 unique, tiny-ass bars.

Where to go? The shockingly pink Love and Peace? The jazz-eclectic Dan-SING-Cinema, up a crippling flight of stairs? (Most of these bars stacked two high.) The geek-chic Bar Plastic Model? Be warned: there will be “seat charges,” either a flat fee or hourly rate to sit your ass down and drink. That's because all these joints have regulars—artists, musicians, writers, whatever—who expect their usual seat (of like eight). Bar-hopping in Golden Gai gets expensive quick.

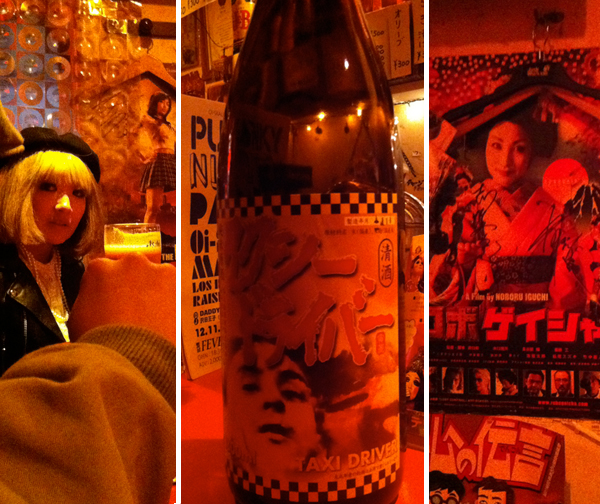

Luckily, I found my Cheers. It's called Darling.

Japanese splatter film posters (Robogeisha and The Machine Girl anyone?)—most of which feature acting by Darling's charming owner Yūya Ishikawa—blanket the cramped space. If Yūya's in the house, then Group Sounds-era crooner Kenji Sawada will be wafting from the stereo. Otherwise, expect jazz or Motörhead, as cutie bartender Ichiko serves a full spread of the harder stuff. To offset that 800-yen seat charge (and dull the booze), Ichiko adds a complimentary snack. One night I swear it was a mini chalupa, likeOrtega-style—I don't know how she made that in Darling's dollhouse-sized kitchen.

The J-Horror world frequents Darling, plus Eiga Hiho journalists like Yoshiki Takahashi (those extra-splattery posters and “Taxi Driver” sake label? All Yoshiki-designed) and noise musicians. If I'm lucky, Tokyo Dolores pole-dance troupe leader Cay Izumi. If I'm luckier, a handful of Mutant Girls Squad actresses.

Last December was Darling's sixth anniversary, coinciding with Yūya-san's birthday and the evidently rare Japanese lunar eclipse. A crowded night of “飲み放題” (“all-you-can-drink”, truly an awesome concept) and debauchery ensued. I'd been frequenting Darling for over a year then, and I never felt closer to home.

If you end up within Golden Gai, I suggest Nagi—a Fist of the North Star-themed ramen joint—as your pre- or post-drinking nosh spot. Nagi's unctuous, garlicky deliciousness is guaranteed to soak up any alcoholic embers. Plus, any woman willing to get near my post-Nagi breath is A-OK in my book.

Images: overhead shot UnmissableTOKYO.com, all Darling photos courtesy the author

The Adidas Originals Facebook page (and the internet at large) blew up after a photograph of a shoe with ankle chains, the JS Roundhouse Mid, designed by Jeremy Scott, was posted this past Monday. Scott said the shoe was inspired by the 1980s toy My Pet Monster. The Reverend Jesse Jackson got involved. Meanwhile, the National Parks Service has plans for an event called “Walk a Mile, a Minute in the Footsteps of the Enslaved” on July 8. Adidas, for their part, have decided to pull the shoe. As Olaudah Equiano reminds us, "apparel" manufacturers were always slow to join the cause of abolition.

1.

“The design of the JS Roundhouse Mid is nothing more than the designer Jeremy Scott’s outrageous and unique take on fashion and has nothing to do with slavery…Jeremy Scott is renowned as a designer whose style is quirky and lighthearted and his previous shoe designs for Adidas Originals have, for example, included panda heads and Mickey Mouse. Any suggestion that this is linked to slavery is untruthful.”

—Adidas statement regarding the JS Roundhouse Mid shoe, 18 June, 2012.

2.

“I hope that the slave trade will be abolished. I pray it may be an event at hand. The great body of manufacturers, uniting in the cause, will considerably facilitate and expedite it; and, as I have already stated, it is most substantially their interest and advantage, and as such the nation’s at large, (except those persons concerned in the manufacturing neck-yokes, collars, chains, hand-cuffs, leg-bolts, drags, thumb-screws, iron muzzles, and coffins; cats, scourges, and other instruments of torture used in the slave trade).

—Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself, 1789.

3.

“Park Ranger Angela Roberts-Burton will be in period clothing telling tales of the enslaved who labored here. Experience agricultural labor that enslaved people may have performed at Hampton. Work in the fields with actual hoes and scythes. Carry buckets of water with a yoke on your shoulders.”

—Publicity materials for the National Park Service’s Hampton Farm Site in Maryland, which is planning an event called “Walk a Mile, a Minute in the Footsteps of the Enslaved on the Hampton Plantation” on 8 July, 2012.

Let Me Recite What History Teaches (LMRWHT) is a weekly column that flashes the gaslight, candlelight, torch, or starlight of the past on something that is happening now. The citational constellations work to recover what might be best about the “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts.” They are offered with astonishment and largely without comment. The title is taken from the last line of Stein’s poem “If I Told Him (A Completed Portrait of Picasso)."

Image: Black Media Scoop

Steven Pinker recently released a salvo against The New Yorker, following Joan Acocella's piece on "proper" language usage. I appreciated Pinker's rebuttal, because I have a reflexive distaste for the insular, middle-length thinking that magazine inculcates in its readers, and because, more than anything, I can't stand language prigs—whether they’re lambasting each other over misperceived errors regarding the plural of "vinyl" or one-upping each other in the quest for stylistic purity by avoiding the prepositions with which the rest of us end sentences.

Why? Because, frankly, they’re wrong.

Pinker’s issue with The New Yorker concerns a supposed opposition between “descriptivists” and “prescriptivists”: respectively, those who think the best way to understand language is with descriptions of how it is actually spoken, and those who want to fathom the real laws of language and judge existing speech or writing accordingly. This opposition is old as the hills and, like many such conceptions, it isn’t really accurate. Nowadays in linguistic studies, things are not so dichotomous. This makes sense: in order to suss out formal rules, you need to approach the seething linguistic morass that gurgles outta people’s throats, and in order to describe how that morass functions in life, you outline patterns that, like it or not, regulate the way words work. And most people who actually delve into language are not so cavalier about claiming to know the final truth about the right stylings of linguistic awesome.

The thing is, Pinker errs in his endorsement of a "standard English." What would that be, anyway? The difficulty with his position reveals itself when he likens “conventions” such as standardized weights and measures to the tacit rules that govern expression within a community. Take, for instance, this analogy encouraging “standard” usage:

But the valid observation that there is nothing inherently wrong withain’t should not be confused with the invalid inference that ain’t is one of the conventions of standard English. Dichotomizers have difficulty grasping this point, so I’ll repeat it with an analogy. In the United Kingdom, everyone drives on the left, and there is nothing sinister, gauche, or socialist about their choice. Nonetheless there is an excellent reason to encourage a person in the United States to drive on the right: That’s the way it’s done around here.

See: there is nothing inherently wrong with either, but we would be poorly advising people if we told them that they could drive on the left in the States. It'd lead to horrific collisions, or at least make road-texting that much harder. Sad.

Problem is, this isn't really apt. Manners of speaking reside far deeper in our psyches, constitute much more of our identities, than familiarity with driving on the left or right side of a strip of asphalt. They constitute our very capacity for describing ourselves, our lusts, aspirations, sexual fantasies, fealties, and relation to the divine. (Intimate things, those.) Nor is language learning managed by the ISO, or other bodies that govern the “conventions” to which Pinker compares standard English; there have been no agreements about what words should be said to infants, and in which order, and it’s unlikely there will be. Hence, the way we speak isn't a practice that can be instrumentalized like driving within a territory—though perhaps children shouldn’t get a speaker’s permit until they turn 15, and only after a bleak, Red Asphalt-style course on hurried sentences and the influence of alcohol on utterance.

Somehow I don’t think that’s likely scenario. And somehow I don't think hearing ain't used in a sentence causes many semis to swerve into oncoming traffic.

Watch this space next week for Part 2 of "Describing Your Prescriptivism."

Image: Planet of the Apes

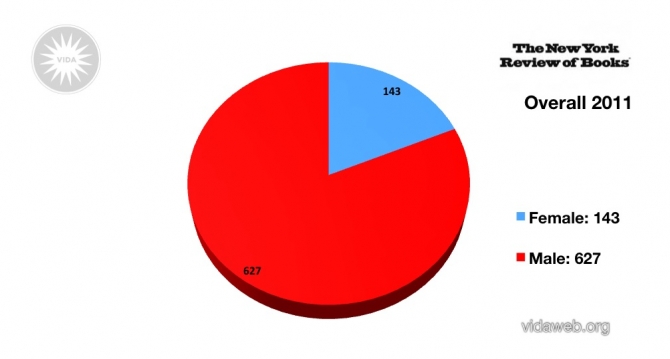

The statistics are in! Thanks to the VIDA Count, there's fresh proof that we live in a world of crappy exclusion in the books department. While I was happy to come across an article in the Irish Times about a retired High Court judge urging lawyers and judges to read great works of literature, I was made profoundly less happy by recent reports on gender and racial bias in publishing. And then I figured it all out: what the judge and the reports suggest to me is a need for empathy, and a need for more people to desire an experience of empathy.

The judge, Bryan McMahon, said that "[l]awyers should be acquainted with great literature and should learn from it. It deals with envy, jealousy, greed, love, mercy, power politics, justice, social order, punishment ... Judging also involves the soft side of the brain, dealing with compassion, understanding, imagining the extent of one’s decision.” Literature has the capacity to peel us away from the world we think we know and take us into an entirely new experience with a changed perspective. This is useful not just as an escape or to serve as some kind of refreshment; books complicate and deepen our understanding of the human experience.

So what happens when almost all of the books that are promoted and discussed in major outlets derive from a largely homogenous pool? Does this limit our access to the great variety of human experience? Could this mean—because of stuff like profitability and basic self-interest—that publishers and reviewers mostly promote the human experience that reflects theirs?

I don’t wish to come off as a big poopy diaper, but in light of the statistics showing that high-visibility literature is mostly male and most definitely white, I think it’s valuable to note that publishing is often a gross machine and often doesn’t reflect very good taste or wise choices. But as much as the nasty, naughty publishing machine is a total idiot with no gumption or integrity, I’d also like to suggest that there could be a fair amount of readers (yeah, the white ones with the money) that don’t much like that which is unfamiliar to them. Readers can just as guiltily say that they want to read a book “they can relate to.” Somehow fifteen dollars has become too precious an amount to spend on something so unnecessary as literature, but 99 cents to download some "guaranteed" blockbuster is a great modern thing.

Think of how the majority of book buyers find books these days. Amazon tells you what other people liked based on what you like. How could this possibly lead to a diverse reading experience?

To top it off, the attachment to indulgence and self-interest is rampant to the point of perversion in this country. I don’t have all my statistics in on this, but I’m fairly certain. And when the self is held as the utmost importance, how could anything of quality be read at all? Does no one want to take a risk or try something new? Maybe readers would enjoy different books if publishers and reviewers spent a little more time pushing different good books and not just the guaranteed sellers for an already established (and at this point, hopefully bored) audience.

image: vidaweb.org

I.

I got lost trying to find Washington Square Park. I can’t count how many times I’ve walked under that white arch, but this time, when I got off the subway, I circled the area for an hour before spotting it.

How did I get lost? I’m not sure if it was the unfamiliar origin, or if maybe it was the rows of summer-green trees exploding throughout the Village. We shaded our eyes against the sun, and somehow I couldn’t find a single familiar thing. I wondered if we were still in New York.

But there was something strangely beautiful in being lost. Every new street looked more real; as I rounded each corner, I slowly built up a mental map from the world around me.

II.

“I am quick to disappear when I walk; my thoughts wander until they cease to seem to be my thoughts, until, mercifully, I cease to think of myself primarily as myself for a few moments.” I read this in a stunning Harvard Book Review essay. The writer goes on to wonder “why I’m so tempted to read the world around me when I walk — especially since I would be so much better served by just paying attention to where I was going and how I was getting there.”

We make our lives out of what we see. Anything we do not see shapes our lives by its absence.

III.

Before I moved to New York once and for all, I read Teju Cole’s Open City. I had been to New York many, many times and did not think of it as a city in which one lost oneself. But every space has its crevices: Teju Cole’s narrator finds himself locked on a fire escape, looking down an unlit side of Carnegie Hall. After his despair passes, he looks up, “and much to my surprise, there were stars. Stars! ... the sky was like a roof shot through with light, and heaven itself shimmered. Wonderful stars, a distant cloud of fireflies: but I felt in my body what my eyes could not grasp, which was that their true nature was the persisting visual echo of something that was already in the past.”

When I moved to New York, it was through an airport; I did not arrive at Grand Central Station, which had always been my port of arrival. But then I took a train out, and as I crossed the main concourse, I looked up for the first time in four years. Above me was a sea-green heaven, with golden constellations dotting the ceiling. I forgot the station momentarily, mesmerized by that slice of the sky.

Do we let ourselves get lost to see what we have forgotten, to witness and retain what we have refused to let ourselves see before?

IV.

I once tried to escape the Midwest by reading Dead Europe. The book, by Australian author Christos Tsiolkas, took three weeks to make its way from the Antipodes to America. And then I read about a photographer who, trying to dig into the wreckage of his family’s and his own past, travels from Australia to Greece and then across Europe.

In Paris, he is taken to the city tourists never see: “a harsh place, a tough, crumbling, decaying, stinking, dirty city ... But the act of adjusting the camera lens, the act of focusing on an image, seemed to alleviate my anxiety.” Photography is only another form of looking, of mapping the things that otherwise would remain terra incognita.

V.

Of course I found the park, but by that time I didn’t particularly want to be there. I had been looking for something else all along, I suppose. So I unfurled the map in my head and followed it away.

image credit: flickr.com/photos/deepersea

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©