My parents were flower teenagers when Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the Moon. Despite cabin-mate Buzz Aldrin's pop culture ubiquity, it was Armstrong's gravely voice — “That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind” — that inspired generations of deep-space dreamers. The lunar legend's passing last week, and a selection of his letters reproduced on mental_floss, got my mind drifting. What if the first moonwalk occurred in the 19th Century? What if classic authors transported their tales to the cosmos?

This is not an easy concept. Resetting novels in celestial environments can result in some wack-ass mashups, and I'm definitely not a fan. I'd make a pitch for Bram Stoker's Dracula — two words: “space vampires” — except it's been done, even inspiring a pretty sweet film adaptation.

Still, I've identified some classics that would convert wonderfully in outer space. Take a giant leap (of faith) with me and read on.

Star Wars Episode VII: Revenge of the Realist

What if Chichikov, of Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls, piloted around Russia in the Millennium Falcon instead of that spacious britzka? Manilov's “Britishly” over-politeness demands gold-toned protocol droid C-3PO, while in-your-face Nozdryov could be any of the bruisers boozing at Mos Eisley's cantina (which, in this version, would be called "Gogol's Bordello.") Sobakevich cuts a Jabba-esque figure, if not in sluglike physique and penchant for malice, then in his shrewd business acumen and voracious appetite. And miserly Plyushin could be Yoda fallen from the Force, and his halcyon garden — shadows “yawning like a dark maw” — the lonely swamp of Dagobah.

Alien vs. Kafka

In The Trial, Franz Kafka conjures a labyrinthine city around accused Josef K, echoing a convoluted, inaccessible authority. Now picture K wandering the gas-spewing corridors of an industrial spaceship, like Nostromo in Ridley Scott's Alien. Sliding doorways and claustrophobic crawlspaces lead not to a drooling Xenomorph but to legions of lawyers, or perhaps batty court painter Titorelli. Though I like the idea of the sadistic Flogger becoming a Facehugger, tonguing K's pitiful arresting officers instead of beating them.

Charlie and the Magic Mountain at the End of the Universe

Except for a few snowshoes into town, The Magic Mountain dwells way up in a Davos sanatorium. Thomas Mann's masterwork could double as a huge-ass spacecraft with breathtaking views and a killer kitchen, combining Milliways from Douglas Adam's The Restaurant at the End of the Universewith the luxurious Space Hotel from Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator. Spacewalks replace young Hans Castorp's meandering strolls with humanist Settembrini and radical Naphta, while Davos' idyllic panoramas could be swapped for crazy shit like the Pillars of Creation. Plus, Castorp's harrowing hallucination in the chapter “Snow” easily translates to deep-space distress.

Neuromancer in Venice

I'd even chance converting the beachfront Grand Hôtel des Bains of Mann's novella Death in Venice into Freeside, the glitzy cylindrical space resort from William Gibson's Neuromancer. Better still, consider sunny Ursa Minor Beta from The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (fine, I'm an Adams fanboy), with its endless subtropical coastlines and perennial Saturday afternoon climate, “just before the beach bars close.”

Told you these re-imaginings aren't easy. If I've implanted any intergalactic mashup ideas in you, jot them down below. And if this all seems a bit far-fetched, I'll leave you with Mann's time-traveling meditation on the Lido di Venezia:

the sea, so bright with glancing sunbeams, wove in [Aschenbach's] mind a spell and summoned up a lovely picture: there was the ancient plane-tree outside the walls of Athens, a hallowed, shady spot, fragrant with willow-blossom and adorned with images and votive offerings in honor of the nymphs and Achelous.

Image: The Magic Mountain cover via the author's own scan + Pillars of Creation via ScienceBlogs, photo-chopped by the author

A weekly series that explores a featured theme by pairing classic quotations with urgent images. What recent news items inspired these textual/visual sets? Leave your guesses in the comments, and check back next Wednesday for the answers.

“It is only too true that a lot of artists are mentally ill — it’s a life which, to put it mildly, makes one an outsider.”

—Vincent van Gogh

“To be an obsessional means to find oneself caught in a mechanism, in a trap increasingly demanding and endless."

—Lacan

“That is why delirium and dazzlement are in a relation which constitutes the essence of madness, exactly as truth and light, in their fundamental relation, constitute classical reason.”

—Foucault

“In the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singtime sung, her rill be run, unhemmed as it is uneven!”

—James Joyce

“Every man can, if he so desires, become the sculptor of his own brain.”

—Santiago Ramon y Cajal

Do you see the connections? Write your guesses in the comments, and check in next Wednesday to find the headlines that inspired these pairings.

Images: twitpic.com/amkkt2, Gawker, mental_floss, New York Times, arch2o.com

Answers to last week's installment:

Everybody loves a good infographic. Need to summarize a complex set of statistics (like, say, alternate band names for Pussy Riot)? Try a pie chart. When scientists have trouble understanding data, they use 3-D imaging to map the invisible patterns of airplane turbulence or visualize how a woman’s hair might rumple if she uses X Brand of shampoo, as illustrated inDiscovery Magazine.

But how do you portray invisible occurrences that are not data-driven? What are my options if I want to visualize the emotional ups and downs of my new favorite song, or understand the subjective history of a public space? Can I get an infographic of some feelings over here?

Here are five artists who are making the invisible easier for us to see.

Music: Andrew Kuo

Andrew Kuo makes infographics based on unreliable information. His minimal, brightly colored graphs chart the unchartable, with a particular focus on music: he might rank the emotions of Kanye West’s “Robo Cop” in comparison to other "great" break-up songs, or plot his reaction to a new 9-minute Joanna Newsom single. If music really is just another kind of math, I want Kuo to be my trigonometry teacher.

Motion: STREB

Choreographer Elizabeth Streb approaches dance like a scientific experiment. In performance and at her Williamsburg "lab," STREB dancers test the invisible laws of motion by throwing their bodies against them. Like, literally. Want to know what gravity looks like? Watch the dancers fly off scaffolding and land hard on their bellies, or balance impossibly on giant spinning hamster wheels. Seeking a spectacle that demonstrates the principle of inertia? Streb's got you covered: dancers run into walls at full speed, duet with lethal projectiles like steel beams, and generally stomp all over the limits of time, space, and muscle.

Cities: Rebecca Solnit

With 13 books under her belt, nonfiction writer Rebecca Solnit has made a career out of exposing subtle truths. (Full disclosure: I once worked for her.) Her 2010 book, Infinite City, visualizes the layered history of San Francisco through maps of seemingly unrelated sites: "Monarchs and Queens" overlays the natural history of the monarch butterfly with queer civil rights history. The result is an atlas of previously unseen connections, a shifting paper record of a living city. A New Orleans version, Unfathomable City, is due out in 2013.

Institutions: Anna Schuleit

There’s the invisible, and then there’s theinvisible — the people pushed beneath the narrative because, as Ralph Ellison’sInvisible Man put it, we refuse to see them. When the Massachusetts Mental Health Center closed in 2003 after 90 years of operation, artist Anna Schuleit was commissioned to create a work memorializing the building. Her stunning installation, BLOOM, filled the decommissioned mental institution with 28,000 living flowers paying tribute to the lives that passed through the space.

Media: Teju Cole’s Twitter feed

There’s invisible, there’s invisible, and then there’s dead. Novelist Teju Cole, author of Open City, tweets about the news — specifically, newspaper notices of death and crime from 1912 New York. He calls the project “Small Fates." Taken as a whole, Cole's timeline is a chorus of funny/sad ghosts. These are the long-forgotten voices of regular folk — criminals, victims, and reporters — a quotidian citizenry of the city, distilled into poetry.

Did I miss any? By all means list your favorite visible/invisible artworks in the comments. Granted, the question of whether what we see is truly "real" is always open to dorm-room-stoner interpretation. But I'm thinking that art has science beat on this one.

Images: BOMB Magazine, Andrew Kuo, Anna Schuleit

The Morning News has decided to play Reading Roulette with six Russian authors, shooting a new one into the American blogosphere each month. And because I can't get enough of translation, I’ll be writing about this year's selections — and linking to each one so you can read it yourself. This week, we consider Nikolai Klimontovich's remonstrative remembrance, "How to Crow Your Head Off."

“Given the slightest pretext,” writes Nikolai Klimontovich in the latest round of The Morning News’s Reading Roulette series, “the prison atmosphere always seems to assert itself in Russia whatever the situation: in elite holiday homes and boarding schools, orphanages, military barracks, even hospital wards. This type of organization seems to be inherent in the national character.”

It’s not endemic solely to Russia — Philip Zimbardo’s infamous Prison Experiment at Stanford implies that any group can internalize the roles of prisoner and guard. But the more corrupt a country is, the more easily it shifts into such a setup. Russia has a Corruption Perceptions Index rating of 2.4 out of 10, a number so dismally low that the New York Times summed it up in a headline: “For Russians, Corruption Is Just a Way of Life.” This “way of life” explains many aspects of Russia, from the astonishing number of car crashes in Moscow to, here in Nikolai’s story, the narrator's turn toward violence.

In "How to Crow Your Head Off," corruption enables a neighbor to shoot the family cat, in turn causing grandmother to bring in disease-ridden strays; corruption engenders the hierarchal structure of the hospital where the narrator is quarantined for ringworm; corruption becomes the best way to understand and master the school playground after he returns to society.

In the hospital, the narrator watches his fellow inmates from the sidelines: “Lousy Letuch ruled the roost, a bruiser ... He had a sidekick, a small — even smaller than me — but very strong lad of 11 called Vovan, who did all the dirty work for his boss.” (How strange that a story set in 1950s Russia can echo the bully and toadie archetypes of A Christmas Story.) And then, fresh out of the hospital and back at school, the narrator is cornered by “a nine-year-old bruiser, taller than me by a head, the spitting image of Letuch, with a couple of Vovans by his side.” What does he do? He recalls the moral corruption at the hospital and tries to fight it in his own way, with a Pyrrhic victory: “I hunched my shoulders, stuck out my head and charged with all my might.” He'd been singing before the fight, and he finishes the song with blood dribbling out of his nose.

Sixty-odd years later, the "bruisers" are manning the Kremlin under Vladimir Putin's watchful eye.

The Russian word for corruption is испорченный (prounounced “isporchenniy”) and stems from archaic Slavic words indicating spoilage or degeneration, while the word for official corruption, коррупция(pronounced “korruptsiya”), bears Latin roots. But the distinction between political corruption and individual corruption is a tricky one to make. The former, indeed, would not exist without the latter; it’s hard if not outright impossible to separate many political officials’ political dealings from their moral stances. When dissidents are punished for expressing their opinions, it's worth noting which opinions are scrutinized — and against whom.

Klimontovich was born in the early Fifties. He is not part of “the younger generation” (as he calls it) that came of age after the fall of the USSR. The younger generation was raised not by the rules of Brezhnev, but by the words of Gorbachev; not under totalitarianism, but with glasnost. But I imagine he feels some spark of recognition with the recent waves of rebellions and outspokenness in Russia, from Aleksey Navalny’svituperative critiques to the Pussy Riot closing statements. Bloody noses and all, they're still singing.

With thanks to Rachel C. for etymological advice.

Image: dvoinik.ru

Indulging in some late-August back-to-school nostalgia, the Daily Beast put together a list of "Must-Read College Novels" ranging from Kingsley Amis’Lucky Jim to John Williams' Stoner. As a fan of college, books, and college books, I thought I’d work up a supplementary list: the principal ingredients that no college novel can do without.

Unfortunate romance

The great thing about romance in college is that it’s either totally doomed from the beginning or the participants are guaranteed to screw it up. At least, this is how I justify my ridiculous relationship with an unsuitable upper classman and the continued obsession I have but could never act on with a simply wonderful professor. Whether it’s faculty, students, or the time-honored tradition of faculty/student infatuation, college is a good time to fall hard for someone who is absolutely wrong for you, but who will continue to tear out your heart with their math skills or commitment to social justice.

College exposes you to romantic situations you are not at all ready for, as seems to be the case in Nathan Harden's new book Sex and God at Yale. You will learn a whole lot about yourself, mostly in the areas of failure and weakness. And it will all seem very important at the time, but not after graduation. Unless you insist on being totally infatuated with past professors, which is completely acceptable.

Blunder

If we can think of adolescence as the time when weird things happen because of our changing bodies, college is like an adolescence for that body being in the larger world. While the awkwardness of high school has passed, the vast and slippery social dynamic of college allows for a whole new set of embarrassments. All college environments have that unique mix of shelter and independence. You have this great chance to redefine yourself, but then you're also more exposed to other people who might actually help you figure out who you really are.

Freedom means that college students will try stupid things (like bleaching your hair). Greater responsibility means that being stupid has more consequences (like having bleached hair). Just ask the characters in Donna Tartt's novel The Secret History.

Illusion of safety

College students are insulated from the real world at the same time they’re learning more about it: their sense of self in relation to the world and the possibilities of what they could do within it are totally exploding and hyper-vivid. And part of the shelter that any college provides is the impression that other people care about your ideas. Any novel can have main characters finding themselves; what makes it a college novel is that characters engage with the same kind of exploration but within a closed system that won’t pan out in real life.

This illusion can also be true for professors, as we learned in Michael Chabon's The Wonder Boys.

Hyper-awareness of time passing

Whether the plot moves forward through the passing semesters or the novel as a whole is a nostalgic look back at such brief time, four years is only four years. College is always in some way about transition. There is perhaps no better illustration of this dramatic shift than Bret Easton Ellis'Less Than Zero. Hopefully, most of us don't find ourselves disillusioned by the party scene in our freshman year because the kids back home were all prostitutes for smack, but who among us didn't experience that same whiff of disappointment — the sense that home had changed without you? The sense that you'd maybe surpassed home?

Serious transition happens with or without college. It's just really, really nice to undergo that transition without your parents looking.

Image: cineplex.com

he world presents itself to us scant-haired apes through our senses. Our attention alights on the warm, flaking brown tactility of a sunlit bench or the gut-tugging stench of rainwet, festered trash, and these details stand out from the remaining mess of things unattended to. Later, a string of sensations can be woven together to give memory the sensible fabric of an afternoon, a first meeting, a childhood. For most people, these sensations are of a distinct qualitative sort: touch, smell, taste, etc. But a very few, synesthetes, perceive one channel of sense as entangled with another. And, if The Atlantic is to be believed, everyone may be able to develop some form of this doubled sense perception.

Read More

“I feel like I’m supposed to be here,” he said.

Kathy was silent.

“It’s God’s will,” he said.

She had no answer to this . . .

Kathy rolled her eyes.

“Of course,” she said.

“I love you and them,” he said, and hung up.

—Dave Eggers, Zeitoun

Let's talk about Dave Eggers's Zeitoun. It's the story of Abdulrahman and Kathy Zeitoun, who survive Hurricane Katrina — Kathy because she left beforehand with their children, Abdulrahman through luck, resourcefulness, and bravery, but not without great despair. Their reunion is perpetually delayed by the strange machinations of governmental agencies who imprison Mr. Zeitoun and consider him a danger, not a hero. We could consider the book a call to action or an act of reportage. Fundamentally, though, it’s a love story.

That story became a whole lot more complicated earlier this month, when Abdulrahman was arrested for assaulting Kathy. Judging by its Amazon rankings, Zeitoun is flying off the shelves again. So what should the book’s publishers do? They’ve already ignored the couple’s divorce, but assaults and arrests are much more difficult to shrug off. It's hard not to read the telephone conversation I quoted above without a new sense of irony.

For print, the options are scant. Jonah Lehrer’s Imagine was recalled and refunds made available. They could print new editions with a preface or afterword, like James Frey's A Million Little Pieces. And let's not forget that the paperback edition of Eggers's first book, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, comes with the upside-down bonus section "Mistakes We Knew We Were Making: Notes, Corrections, Clarifications, Apologies, Addenda." Basically, that's how physical books are handled — as products of a specific moment, with cumbersome revisions.

But what happens with e-books? Technically, they can adapt to the shifting fortunes of their content. In Zeitoun, I'd love to see footnotes that acknowledge what Eggers couldn't have known earlier. I'd love the backstory to this statement to the press.

I’m reminded of Black Balloon publisher Elizabeth Koch’s essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books. She wonders what would happen “if, through evolving books, we could somehow shock ourselves awake enough to recognize that we hold the power to narrate, and live into, a different story of our lives.” As for readers, so for writers and their subjects: these e-bookscan change.

So far, evolving books are hard to come by. (Example? Oh, I don't know...there is Louise: Amended, the latest Black Balloon title.) But the possibilities are dizzying. A Farewell to Arms could incorporateHemingway's 47 alternate endings seamlessly, without an appendix. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance could let its readers map their own journeys onto Pirsig's — ditto for Kerouac. We've seen the Waste Land app, but what if we could pull up different performances of Waiting for Godot(especially Robin Williams and Steve Martin's run) whenever we wanted to see Beckett's words made flesh?

So many books can be unshackled from their origins in a specific time. The original words don't change, but our understanding of them does, and the possibilities are limited only by what our technology can do. We've invented e-books; now we can let them evolve.

image credit: flickr.com/photos/gruber

Forget what you see on 4Chan and Reddit, some people think that the Internet is becoming too nice.

Though the Twitter-war that escalated from a harsh book review suggests otherwise.

Not to mention the smackdown that was William Giraldi's review of Alex Ohlin's latest book.

Perhaps those people should go into bookselling, where things seem to move at a much more pleasant pace.

In fact, that community can sometimes bring about miracles if they set their mind to it.

Hey, even the porn industry is experiencing a renaissance in the literary fiction word.

But if that career option is moot, you could always try writing your own version of Tolkien's classic trilogy.

But we hear there's an innovative new book coming out soon that might even be --dare we say-- better?

Onscreen shagging to a boom-chacka-chacka soundtrack remains stigmatized in puritanical America. Despite the distinguished lineage of adult talent in non-pornographic films — a list longer than John Holmes'super-schlong — porn stars rarely cross over into more "legitimate" areas. Lit-lovers will want to read on, though: starlet Kayden Kross is making waves as a published short-fiction writer.

Before we check out her fiction, as well as the more mainstream work of some of her colleagues, a few guesses at the life of a porn star.

If we learned anything from Charlie Sheen's winning porn meltdown last year, it's that adult-industry performers have flexible schedules — particularlycrème de la crème “contract girls.” As Capri Anderson's manager explained, high-end actresses shoot typically four films a year, spending two to three weeks on each. Even with exclusive endorsements and appearances, that's still over six months free.

Some preferred outlets of porn diversification are a bit...obvious, like reality TV (try Googling “Survivor + pornstar”) and liquor (if Jesse Jane's goddess-inspired tequila doesn't wet your whistle, try a swallow of Ron de Jeremy). Autobiographies are customary, too, perhaps none as famous as Jenna Jameson's New York Times bestseller How to Make Love Like a Porn Star: A Cautionary Tale.

So here's what's groovy about Kayden Kross: her contribution to Harper Perennial's Forty Stories positions her with Jess Walter (Beautiful Ruins, National Book Award-finalist The Zero), Blake Butler (There Is No Year), and other young or established writers. In the collection's sparse bios, the only indicator to Kross' onscreen persona is a sorta cheeky (NSFW) website tag. “Plank,” which first appeared on her blog, reads like a breathless, second-person lucid dream:

You threw your head back and faced the sky and watched the way the green never caught up to the blue, watched the way they spun when you tried to stay too still.

A major tease in 1,400 words, way more so than Kross' multiple roles inPerfect Secretary: Training Day. Besides the repeating “screaming and wet” line, “Plank” isn't overtly sexual. See for yourself. And her long conversation with The Instructions' Adam Levin is worth a read while awaiting her next short story or Complex column.

So who else is equally talented in porn and prose? I'm a fan of alt-porn performer Zak Smith's vivid, figurative artwork, like his 2004 Whitney Biennial contribution: page-by-page illustrations of Gravity's Rainbow. Smith's visual memoir We Did Porn combines sexy, acid-toned portraiture with postmodern asides on tentacle porn (see above; there's that Pynchon again!) and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Kross' bosom buddy Stoya gets geektastic gold stars for reading Terry Pratchett and (very NSFW!) William Gibson. Plus, she debuted Stoya's Bookclub, video-reviewing Chad Kultgen's Men, Women & Children alongside Kross.

C'mon, Stoya, let's see that insight in print, preferably in the post-Neuromancer realm! A sexy screen starlet writing sci-fi — now that turns me on.

Image: 100 Girls and 100 Octopuses (detail) via Zak Smith

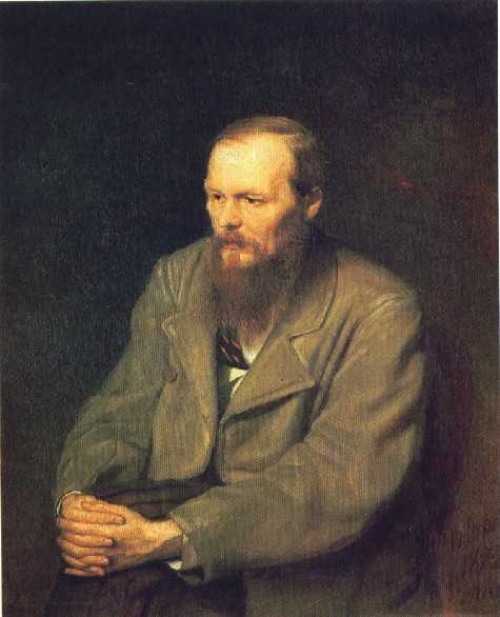

My first bout with consumption happened in junior high. Tuberculosis has a long literary history, complete with a dedicated Wikipedia listing, but until I wrapped my pubescent mitts around Crime and Punishment, I didn't associate it with consumption. To me, TB meant Mantoux tests and subsequent Masters of the Universe action figures as reward for sitting still. But Fyodor Dostoevsky unveiled a world of impassioned and desperate players, literally “consumed” by the harsh world around them.

Below are three cherished Dostoevskian consumptives, from the physically frail to the societally suffering. Dostoevsky newbies, you'll also find some emblematic quotes to whet your appetites—all from the superior Richard Pevear/Larissa Volokhonsky translations. I've tried to keep it spoiler free.

The Idiot: Ippolit Teréntyev, ailing atheist

My favorite Dostoevsky novel features such enduring characters as the “idiot” Prince Myshkin, a kind, innocent—and widely appraised as “Christ-like”—epileptic, and the bubbly Aglaya (I always preferred her to the femme fatale Nastassya Filippovna). Add to these the iconic, flush-cheeked, suicidal consumptive Ippolit. The 18-year-old's plot-stealing aside “A Necessary Explanation!” contains some of this emotional roller-coaster's most forsaken prose:

Isn't it possible simply to eat me, without demanding that I praise that which has eaten me? Can it be that someone there will indeed be offended that I don't want to wait for two weeks? I don't believe it; and it would be much more likely to suppose that my insignificant life, the life of an atom, was simply needed for the fulfillment of some universal harmony as a whole.

The Eternal Husband: Liza Trusotsky, casualty of circumstances

I'm haunted by Liza, born of a clandestine affair between dashing Velchaninov and consumptive Natalia. Velchaninov senses Liza's suffering and tries to pry her from her abusive, cuckolded “father” Trusotsky. Liza's torn existence between Velchaninov, who truly cares for her, and Trusotsky—who, despite his cruelty, she still loves—resounds in her departure to a foster family:

“Is it true that he'll [Trusotsky] come tomorrow? Is it true?” she asked [Velchaninov] imperiously.

“It's true, it's true! I'll bring him myself; I'll get him and bring him.”

“He'll deceive me,” Liza whispered, lowering her eyes.

“Doesn't he love you, Liza?”

“No, he doesn't.”

She succumbs to fever, and though Doestoevsky never explicitly calls it consumption, the implication of wilting under the world's pressure, abandoned first by her “real” father Velchaninov and then by her booze-addled “father” Trusotsky, is deafening.

Crime and Punishment: Sonya Marmeladov, self-sacrificer

The interplay between sickly Katerina Ivanovna and stepdaughter Sonya evolves consumption beyond illness. While Katerina defies a crowd (“I'll feed mine myself now; I won't bow to anybody!”), coughing up blood before her terrified children, I feared most for Sonya. Her world threatened to “consume” her, as she prostituted to support her younger siblings. Add her unyielding devotion to Raskonikov, the impoverished student behind the novel's murder:

Stand up! Go now, this minute, stand in the crossroads, bow down, and first kiss the earth you've defiled, then bow to the whole world, on all four sides, and say aloud to everyone: 'I have killed!' Then God will send you life again. Will you go?

And...she doesn't break. Altruistic Sonya follows the condemned man to Siberia.

This is why I am hooked on Dostoevsky: for conjuring such compelling “consumptives." Though I may not relate to their hardships like I do Haruki Murakami's everyman boku, it's thanks to Dostoevsky's fully-realized creations that I want to know them. Raskolnikov says it best:

Suffering and pain are always obligatory for a broad consciousness and a deep heart. Truly great men, I think, must feel great sorrow in this world.

Image: Vassily Petrov's Portrait of F. M. Dostoevsky via Rhode Island School of Design

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©