When I volunteered to help German artist Sonja Alhäuser make sculptures out of butter, I pictured something sensual. After all, don't you find, among the synonyms for butter, "lubricant"? Or, "lubricate." Alhäuser would be orchestrating a "catering performance" at the opening of an exhibition about shared meals as art practice called Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art at University of Chicago's Smart Museum in February of 2012. This exhibition, which included documents like Filippo Marinetti's 1930 Manifesto of Futurist Cooking, objects like Laura Letinsky's photographs of table-top aftermath, and a slew of events and performances including Michael Rakowitz' traveling Enemy Kitchen food truck, will travel, in adapted form, to the Blaffer Museum in Houston (August 31, 2013 — January 5, 2014) and SITE Santa Fe (February 2014 — May 2014), followed by other venues yet to be announced.

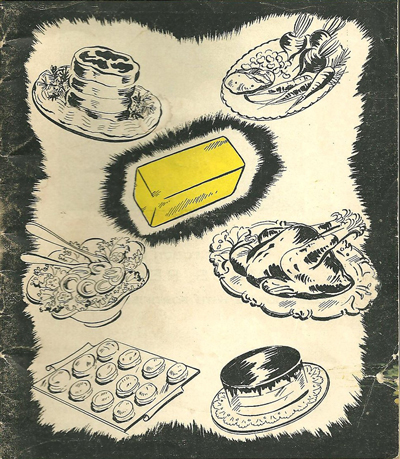

And look at the butter sculptures we'd be making, the reveling baroque creatures that Alhäuser has become known for in a decade of sculpture and performance with foodstuffs like marzipan and chocolate: Thigh-height (although propped on an overflowing banquet table, they'd look visitors in the eye), a bellowing fish-tailed sea god, spewing forth from a butter wave; a mounting turbine of entangled puti with messy ringlets, fat thighs askew; and as if the tablecloth were the surface of a pond, a naked woman, flesh dyed algae-green with watercress, emerging with just her tits buoyed up over the surface. Sorry, her breasts. It's hard to hold a classical vocabulary in your mind or your mouth when you're looking at forty pounds of Swedish Gold margarine. (Margarine holds its form better than butter, apologies to Jennifer Garner.)

There is surprising poetry at the heart of margarine: The French chemist Chevreul who first isolated fatty acids and noted their nacreous sheen pulled the name from Margarites, Greek for pearl. So the French invented it—an 1869 patent resulted from government-sponsored research sparked by anxiety about population growth and food shortage—but the real boom happened after WWII, partially the result of butter rationing. Germany was Europe's highest producer of margarine throughout the cold war (the Dutch a close second) and still was as of 2001.

Let me appear as the Ghost of German Margarine Eroticism Past and spirit us to three scenes: One, a Lätta-brand margarine TV spot from the 1980s featuring a hot West German yuppie couple. He high-fives his way to work, where he reads a Financial Times in front of a prop computer and later practices knife-throwing for sport; meanwhile fraulein kills it at a board meeting and then challenges herself with a sick jog along the boardwalk. They tangle at home with their pants off, while the domestic version of Van Halen scorches his trachea with the brand's name. Their bodily health and professional drive are the mere coefficient of the awesome sex they have before and after eating margarine every morning.

Cut to a 1998 TV ad and we're properly in Alhäuser territory: To the sound of a cowbell hammering out just three primitive iron-age notes, a naked woman with a great pair of naturals pumps across a crystal-clear lake and then emerges at the shore, a live-action version of Alhäuser's watercress nymph. She pulls a box of Lätta out of the water. I won't describe the rest except to say that I wonder whether a family of four in the suburbs of Stuttgart dining in front of the telly grinds to an awkward halt as the ad airs and they collectively realize that the margarine parked on their table next to a heap of potatoes is what I think is called a "tickler."

Most likely, nothing grinds to a halt, because nudity is naturalized and I'm just being a squeamish American, but by a 2002 Lätta ad, our third stop, I have to throw my hands up: Yikes to the family in Stuttgart, because it's just a naked threesome in bed.

A rich medium for an artist, no? No one walks out on a threesome for acrylic paint, anyway. And the baldness with which corporate marketing has turned this oleaginous lab-rat into something as timeless and natural as alpine lakes and the sex drive of healthy adults is ripe for an artist's critique. An imposter of luxury (its first name was beurre économique, or "thrifty butter"), margarine would travesty bronze in Alhäuser's final banquet, and invite the conversation that so frequently attends food in contemporary art: Food demands engagement, not contemplation—it breaks down the intimidating authority of art, it destroys hierarchies. Take a 2003 Gastronomica article about Alhäuser: "Don't we arrange our sculptures on pedestals, and contemplate aesthetic at arm's length? … Alhäuser thumbs her nose at such convention." So while a gilded eros decorates a palazzo somewhere in Europe, you get to swipe the smirk off Alhäuser's Swedish Gold gods with a Dinkel's pretzel roll and then wash it down your throat with an Amstel Light. You don't need élite knowledge to get it; teeth will do.

But I realized the day of the opening is that a major part of Alhäuser's work had nothing to do with destruction or glee or breaking boundaries on the part of the public. That's all there of course. But turn 180 degrees, away from the gallery, away from the margarine bosoms (sorry; we'll come back to them) and the baroque banquet, toward the usually invisible guts of the museum itself, the warren of offices with their own hierarchy, the neatly labeled one of the museum staff. Alhäuser asked the staff (aided by volunteers) to do everything but sculpt margarine. She needed caterers. So she turned the museum staff into a catering staff, who over the course of a work day assembled hors d'oeuvres for 400 people. We were asked to cut canapés and toasts, to shape marzipan from molds, to skewer chicken and peppers, melon and strawberry. In fact, much of what we did involved skewers, and "skewers" is a word designed to make German mouths flap and deflate like a balloon released.

"Skeeeuuusssssss?" Alhäuser ventured at the planning meeting a few days before the opening, tucking her chin down and scanning the museum staff for recognition.

"Skewers," offered the Events Manager, who had spent the morning at Whole Foods buying "artists' materials."

"Skyeuuusssss," said Alhäuser, reassured. A baby hung off her hip (the danger of exposure to margarine.)

I thought we were all in love with her at that moment—she is a warm woman with a wide smile whose work, after all, stages act after act of generosity—but I was wrong, because the night of the opening, the volunteers mostly bailed. Alhäuser had seen worse. At a summer event in Berlin four years ago—recounting this to me, she didn't want to name names, given the hostility that had ensued—she had proposed an ice sculpture and when she showed up, there was no refrigerator.

"They think artists can…"— she struggled for words, holding up a spatula covered in green margarine—"they think I am like magic, I make everything from nothing. But I need everything a caterer needs—even though I am an artist."

Ideas of artistic magic on the side of production couldn't have been harder to sustain as offices behind the gallery space filled with raw materials in vats and sacks that needed to be broken down and somehow reassembled into the dancing Rockette kicklines of bite-sized delicacies that Alhäuser had drawn.

So we got to work. The Finance Director, a short, hardy woman who had wrapped a bandana around her head Rambo-style was melon-balling next to a stack of papers in her office, which had become the dessert laboratory. When Alhäuser passed through, suggesting that perfect spheres might be too demanding, the Finance Director looked up from under her bandana: "I've got a degree from the Culinary Institute in Hyde Park. I've cooked all over Europe, New York." The Grant Writer and I let our hands fall for a moment and stared at the Finance Director, who melon-balled with a fire in her belly.

Some rose in the ranks—the Study Room Supervisor had a small side business baking cakes, and authority accrued around her steady hand—while others' efforts were more perfunctory. God love the Executive Director, leaning on a radiator in the conference room, plucking leaves off stalks of mint, a little electrified by the fact that there had been more RSVP's for this opening than for any in the museum's history. His readiness to serve as mere infantryman was apparently exceptional:

"Museum chiefs," said Alhäuser, "they don't ask me what I want—they just do. So I like working with these people." Here she gestured at the Education Director, a recent hire, about thirty years old and in his best suit, who was spreading smoked trout on pumpernickel squares. He circulated the opening that night reeking of the summer gutter waters of the Gdansk fish market. Every time he waved at someone that night, a fox in upper Michigan stopped moving and raised its nose, tracking.

"Do I have a choice?" asked the Education Director. Alhäuser responded with a maniacal laugh.

From the marzipan-molding workshop down the hallway came, in cheerleader crescendo, "Goooooo DEVELOPMENT!!"

Alhäuser observed the chaos around her coolly; she'd visited it upon other institutions.

"Often I have no kitchen in museums—often it is a mess like here." Beat. Smile. "But I don't need to clean it in the end."

After a few hours, it no longer seemed strange to hear "We moved all the peppers to the Security Office."

We were too zoomed on our various chores to note what no one at the exhibition would see: As Alhäuser confirmed to me in a recent email, "In the process of arranging the tasks the hierarchic structure of the museum disappeared completely."

Finally at the opening, burned out in that feel-it-in-your-heels, post-Thanksgiving way from five hours of the repetitive, Lego-building finger-work of making canapés, I found myself leaning by the museum entrance at first alone, and then suddenly face-to-face with a towering, magnetic sorceress I knew was Marina Abramovic. Abramovic had recreated the staging of a 1979 collaboration between Abramovic and Ulay entitled Communist Body/Fascist Body for "Feast": Two tables, one set with sterling crystal, champagne and caviar, and the other with paltry Russian equivalents. Serbian-born Abramovic went from respected performance artist to global celebrity after her 2010 retrospective, "The Artist is Present," in which she sat in a chair at New York's Museum of Modern Art for three months and stared across the table at strangers who showed up to face her. She has spent the past forty years cultivating her bodily self-possession through rigorous training in physical endurance, mental self-awareness and the tolerance of pain. It's not because I know she's done it that I can imagine her handing you a gun and saying you're free to shoot her. She just seems more than human, more strong and more living, drilled out from the deepest layer of earth where rock is still solid.

She's actually been drilled on by plastic surgeons more recently, and it's a strange concession to bourgeois convention that she purchased the lips you'd see at a country club in Beverly Hills, but somehow her magisterial presence—the floor-length gown, the slow motion—made me believe this was simply how faces age on the dark agate planet that shot her to earth. She couldn't have been more different from Alhäuser, who was running around in jeans arranging snacks on a table—such an ordinary activity, even trivial. Nothing magical, nothing superhuman. The "catering performance" went well—students dressed as futuristic sex bombs (who we know, consistent with German marketing lore, love margarine) paraded the sculptures around.

People consumed them. Whatever we may have to say about the radical engagement of spectators by food in the space of art, it struck me that something just as radical might happen to museums themselves—their layout and organization, their staff and management—as, more and more, they find themselves literally catering to food as a medium.

Smushed against Abramovic a fraction of a second before the room collectively realized that the "Artist is Present" artist was present and slid at her like cargo in the hold of a tacking ship, I succumbed to her celebrity and played the obsequious journalist: "What do you think of food in art?" She curled her swollen lips down and said, "Food and art is good." Abramovic is in the process of building the first dedicated museum of performance art in Hudson, New York, and in retrospect, surrounded by visitors lawfully stabbing margarine nymphs with the Development Department's marzipan skewers, I should have followed up: "Then in your new museum, Ms. Abramovic, how big will the kitchen be?"

Credit: Top image, Flickr. All others, Sonja Alhäuser, Flying Feast, 2012. Catering performance with butter sculptures, marzipan sculptures, various foods, miniature watercolors at the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago. Courtesy of the artist.

A series in which we delve into a foreign slice of NYC life. This week: Chinatown Gamers. On the first block of Elizabeth Street, #6A, Nebulous, is a store and tournament center for Magic and Yu-Gi-Oh! card games. I walk by there every night, and every night it is packed with gamers. I decided to visit on a Friday night to understand the place's popularity, and its population.

In the final installment of Building Hamlet, set designer Meredith B. Ries offers her final reflections on what she considers "[an] experiment with blending humor and tragedy, evil and humanity... a dark jibe at religious faith, at royalty, at ambition. [Hamlet is] a ghost story and a love story."