It was a phrase we both used. We liked the ring of it, I suppose. It was a convenient phrase and it came in handy. Anytime anyone asked what religion I was—often worded simply as what I was—I answered the same way. And my cousin Carolyn answered the same way, too. Lapsed Catholic.

The phrase wasn’t unique, picked up from an aunt, or maybe overheard in a conversation. Lots of people used it. But that’s no matter. My cousin and I treated the phrase as our own. It came up as we were pulling through the dry rust of New York into bluer Connecticut.

“Because you can’t be a lapsed Presbyterian, or Lutheran, or Baptist,” Carolyn said, looking at me from behind the steering wheel. “A lapsed Baptist. That just sounds ridiculous.”

“A lapsed Southern Baptist,” I added.

“Ridiculous.”

“So how can you be a lapsed Catholic?”

“I don’t know, Daniel. You just can.”

“That’s true,” I said.

We were on our way to Cape Cod for Easter. Carolyn worked in D.C., and I worked in Baltimore. We decided it would be easier if we took one car to see our family. Neither one of us had much money, though she had a little more. She’s also a little older, though I’m smarter. That’s a hell of a thing to say, I know, but it’s true. She’s more attractive. I’ll give her that.

We’ve always been pretty close. For no good reason beyond familiarity, really. We grew up together. Took baths together, scraped knees together, snuck drinks together. She’s a good person. We’re both lapsed Catholics. It kills our parents to hear us say it. Her mother’s the best. Puts her hands over her ears and says, I’m not hearing this, Carolyn, I’m not hearing my only daughter singing with the devil. My mother’s not nearly as fun. She just gets red and sad and brings up a favorite phrase of her own. Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Or sometimes Holy Mary, Mother of God.

“I’m not saying we’re better or anything,” Carolyn said.

“We?” I asked.

“Well, we’re culturally Catholic.”

“Right.”

We were going eighty-five miles per hour in Carolyn’s Honda. The windows were halfway down, and Carolyn’s hair kept getting wrapped around her sunglasses. She had long blond hair. Sometimes her hair was red. Originally, it was brown. For Easter it was a stylish blond. Festive but respectful. She was wearing jeans and a sweatshirt, though it was understood she’d change into something nice for Good Friday.

“You know, everyone smokes cigarettes,” Carolyn said.

“Everyone?”

“Not everyone, but all adults. They sneak them. It’s a big secret.”

“Like Uncle Richard,” I offered.

“Exactly like Uncle Richard.”

Mostly, Carolyn kept the car in the far left lane. Sometimes she passed cars on the right. She slowed a little when she went up hills. She noted the different restaurant logos on the large rectangular signs off the highway.

“Wendy’s. Do you like their hamburgers better?”

“No,” I said. “They always sort of taste like eggs to me.”

“I do.”

There was no music playing. Carolyn wouldn’t allow it.

She said that people should talk in cars, that people don’t need music. Some of the best conversations she’d ever had were in cars, Carolyn explained, and there was never music playing when they happened.

“We should talk,” I said.

“Sure.”

“How’s work been?”

“Fine. Busy.”

“How’s Allan?”

“He’s good. A little fatter.”

“Really.” It seemed like a funny thing to say. “How much fatter?”

“Quite a bit,” she said.

Then it was the part of the highway where the ocean creeps up from behind the pine trees and stretches out along the road. In Fairfield, Connecticut, the ocean is a flat, disinterested blue.

“I always forget you can see water here,” I said.

“Allan’s been difficult lately,” Carolyn said.

“Difficult?”

“We don’t talk. Not at all.”

We passed a harbor with clean docks and still flags.

“You like to talk,” I said.

“I know, Daniel.”

“I don’t mean that in a bad way.”

“You do, but that’s all right.”

“Have you talked to Allan about this?”

“What’s there to say?” she asked. “He’s bored with me. I bore him.”

“You don’t know that.”

“How’s Shannon? I like her.”

I’d met Shannon two years before in Baltimore, my first year out of college, when I had a part-time job with an ill-tempered history professor at Goucher. The professor was trying to put all this information—I say information because I never really found out what he was researching— on the internet. The department was pressuring him to do it. Throwing lots of money at him. But the professor was old and tenured and didn’t have any real interest in putting anything on the internet. So I did a little paperwork, and he reorganized the project each week. There were a series of false starts, as he called them. Shannon was one of his students. I got to know her after she stopped by his office.

“Shannon’s doing well,” I said. “She graduates in a month.”

“What’s she studying again?”

“Economics.”

“So she’ll be making the money,” Carolyn said.

“I guess you could say that.”

“Would you say that?”

“I guess.”

Shannon isn’t Irish but she has an Irish name, and that had been enough for my family when she came to visit. What do you mean is she Irish, I heard my mother say to my grandmother in the kitchen. Her name’s Shannon. Do you need her to do a jig on the living room table?

“Shannon’s very attractive,” Carolyn said. “She has those eyes. You can have boring brown eyes and you can have beautiful brown eyes, and hers are beautiful.”

“I know.”

“She should do something with her hair, though.”

“Her hair is sort of long.”

“She’d look better with shorter hair. More professional.”

The speedometer bounced to ninety. I was keeping an eye on it. I never drove this fast on my own. Except for the first day. The day I received my driver’s license, I pushed my mother’s Buick to a hundred, then took my foot off the pedal and coasted. It was near midnight when the highway was empty. As a teenager, on my own, it seemed important to go a hundred miles per hour.

“You love Shannon, right?” Carolyn asked.

“Yes.”

“I don’t know if I love Allan anymore. It’s hard to tell sometimes, you know?”

“It is.”

“You don’t know. You’re in love. You don’t know anything when you’re in love.”

“You know some things,” I said.

“No, you don’t know shit,” she said, staring at me with her chin crunched up and white. “It’s the greatest thing in the world.”

“Carolyn,” I said.

“What?”

“Carolyn—”

When I was sixteen, I worked with my Uncle Richard at an auto shop in Harwich. I learned, among other things, that the brake system of cars is twofold: There is a foot brake and a hand brake, and the hand brake is the emergency brake. The emergency brake, I knew, was what you used when you were parking on a steep incline or coming upon a yellow light too quickly. It was what you used, as I later found, when you were driving ninety miles per hour on the highway, and your cousin said your name, said it twice, because there was a car in front of you, and you were going to hit it. The emergency brake was what you used when you engaged the foot brake, but the foot brake froze (too much pressure for the hydraulic pump), and you didn’t know what to do, how not to kill your cousin, the way not to die. I knew, from sulking around the shop while my uncle heaved over engines, that the emergency brake affected the rear wheels only. That the front wheels kept moving. That they were as unaware of what was happening as your body, which was only your body, and not you. You were somewhere else, sheltered from the sudden physics of it all.

That, I knew, was a gift.

Everything else, I did not know. How, for instance, time slows. How time, as if removing a watch face, or opening a man’s chest, quiets to show you how things work. How when time slows, you see that the subtle movements of the universe are not beautiful, as you always suspected, but awkward. How surprising that is.

When you have time, you see that human faces are forever moving and that smiles are easily forgotten in the mechanics of blinking. You realize that sound is always detached from sense in the way that thunder follows lightning.

You find that tastes, to your frustration, do not leave your mouth. When time slows, you understand that there is no time to panic because there is too much time for reaction to function. So instead of reacting, instead of saying your cousin’s name for a third time, you think, I am still here. There are green veins thick across my hands. My breaths are long and uninflected. You do not think, as you may have thought, We’re going to hit that car. Or, perhaps, This wasn’t my fault. You do not think, as the car slides into the middle lane and then the right lane, of any of the things you expected to think about before dying.

Here is what happened. Carolyn slammed the brakes then pulled the emergency brake and finally turned the wheel hard to the right. All of that happened in one second, or so it seemed: Those actions were the last in normal time. After that I expected my life to flash before my eyes—that was supposed to come next—but instead I saw something different.

What I saw, with perfect clarity, was Shannon on the first night she came to my apartment. She was wearing an amber blouse and black shoes and a knee-length black skirt. Her hair was folded into a tight, brown knot. She wasn’t wearing makeup—she never does—but she was wearing just enough lipstick to make you wonder if she was wearing lipstick, and that seemed right. All her movements, I understood as I watched them again, were calculated. The way she crossed her legs and gently ironed her skirt with her hands when sitting. How long she lifted her eyebrows and looked at me when I offered her a drink. She refused the drink, and that was calculated, too. I made myself a highball and put a glass of water on the table in front of her. We sat on the couch and didn’t say anything for whole seconds until I asked her if she liked jazz, and she nodded. I got up and put on the only jazz album I owned. The trumpet came in on the first track in a sad, desperate sort of way, and it made us both nervous. Shannon asked me if I liked jazz, and I said that I was just getting into it. It was ten o’clock, and we didn’t have any plans for the night.

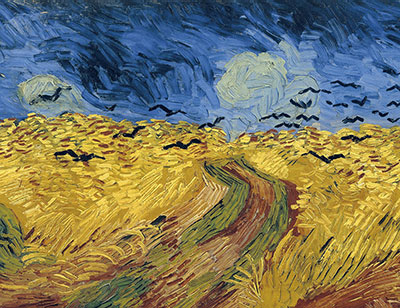

Shannon put her hand on the library book lying on the table and asked if she could look at it. She placed the book square across her lap, and I came closer and explained that I’d checked it out because I was going to see the Van Gogh exhibit at the National Gallery, and that I didn’t know much about his work. She told me she’d only seen his paintings on posters in dorm rooms. The sunflowers, the purple room with the crooked bed. Everyone likes the starry night, she said, but I don’t care for it as much. She told me she’d seen one with sailboats that looked like they were tied to the edge of the painting, and it was her favorite. We looked for the painting in the book and when we found it, she smiled and said, Yes, that it was the best one she’d ever seen.

I told her about the painting I’d been looking at. That it was the only one I’d really been looking at. I told her that it was going to be at the National Gallery. That my friend had said it was the last painting in the exhibit, and that it was appropriate because it was the last one Van Gogh ever finished. Real long, my friend said of the painting, and bigger than you’d expect. It looked, he said, heavy. We were sitting closer now, and I placed my right hand on her back. She flipped to the end of the book, figuring the painting, if it was his last, must be the final burst of color before the columned regularity of endnotes and the index. It was. She ran her hands across its glossy surface. I feel like I should be able to feel the thickness of it, she said, staring at her own fingers. They should make them so you can feel the paint strokes.

We looked at the painting for a while, not saying much, just looking. Shannon began tracing her finger along the road in the middle. When her finger reached the horizon, she picked it off the page and asked, Why do you like this one? It’s the pictures, I said without really thinking, my right hand stretching in the air behind her back. They’re inside the painting, I explained. Faces and shapes. Bending, breaking. They’re everywhere. She touched her neck. I can show them to you, I said. They’re in the strokes. He put them there.

Shannon brought the book near her face, and I couldn’t see her face, so I thought about what the painting looked like. I said to her, There’s a lot of yellow in the painting. There’s a lot of blue, too, but there’s so much yellow. There are no trees to break it up. Only wheat. There are crows, flying out of the black, carrying the black with them, leaving the night blue. They’re making space for a moon, I told her, but it might be a sun, or it might be both. There’d be more black in the night if it weren’t for the crows. Or more blue if it weren’t for the night. Shannon held the book in front of her face. The red and green don’t really change anything, I continued. It’s just yellow wheat and black crows. I paused, thinking about what Shannon looked like behind the book. But the pictures are in yellow, I said. That’s all I meant to say. That they’re there.

Shannon steered the book back and forth, adjusting her vision. She asked, How do I find them. Look closely, I said. Forget it’s a painting and just think of the colors. Or the strokes. Follow the movements. You’ll forget it’s a painting. You’ll forget I’m even here. She lowered the book and smiled and then raised the book. It was the last time I saw her face. Not ever. Not the day it happened. But the day I was seeing it all again. It was the last time I saw her that day. Because the car was slowing—the wheels gaining traction, the engine cooling—and we weren’t going to die. We were going to stay alive, and there wasn’t going to be any more time.

But I needed more time. Time for the shapes to twist out of the strokes. Time for the faces to say something, or nothing, in yellow or blue. Time for Shannon to see it happen. Because she did. When she saw the pictures, she made a sound, neither voice nor breath, but merely a manipulation of air through lips and teeth. Time knew this. Heard the sound. Saw how the oxygen shrank. Felt the slight change in temperature that accompanied it. Time feels most intensely the currents that navigate endlessly through and around the things that make up the world. Time knows too well that before there was time, before there was anything, there was air, nameless and contained in a pocket darker than any hole in history, and only the size of a human fist.

Time would not remember, though. Time would not bring back the force of Shannon lowering the book and saying, with all the unused momentum of twenty years, I see them. Time would not recall her gently saying to me, Daniel, they’re everywhere. Time refused that moment, her face, entirely.

The car righted itself—amazingly, unexpectedly—and we did not die. It was as if nothing had happened.

In some ways, that seemed right. There had been movement, but there were no real marks. Carolyn was crying, but that would pass. Only seconds were missing. Wouldn’t driving to the shoulder, getting out of the car, stretching, take longer than the time it had taken to swerve, tremble briefly, and stop?

Still, in another way—in the only way, perhaps—it was wrong. Something had happened, if only the crafting of an absence. I knew when I met Shannon that she could walk the three flights to my apartment, that she could refuse drinks, hold books, ask questions, of course. But that she could say my name, Daniel, and have it different entirely.

I didn’t know that. I didn’t know until my cousin began crying, until the car stopped, that I could never reach that moment again, that the sound was impossible.

Carolyn and I are lapsed Catholics. The same Carolyn who crossed herself—out of practice, going to the right before the left—after pulling the emergency brake. The same I who hoped to see Jesus—bearded, with soft eyes and a long robe—stepping out of the clouds when the car stopped. I never stopped looking up during my prayers, never ceded the idea that Heaven floats somewhere above us. As if God presides over a kingdom reachable by mountains or ladders. As if Heaven were a New World somehow missed by satellites and planes, and not a different universe entirely, one removed from the unwilling and inconsolable. What would it take, I sometimes wondered, to believe in God beyond fear or obligation? Why could I phrase the question only in terms of loss?

It wasn’t God. It was Shannon’s face. It was not dying. It was facing the wrong way on the highway, the cars coming closer, so that I could see their faces, some bothered, others aghast, one yelling through the window, saying something too far off to hear. The cars were coming closer, indifferent to time, or time indifferent to them, moving in normal time and slowing when they saw us in the middle of the highway, facing the wrong way. Something needed to happen.

Carolyn couldn’t stop crying. It was strange how calm I was.

I didn’t say anything to Carolyn. Instead I said to myself, Soon she will get it together. Soon we will drive to the side of the highway and get out of the car. Soon this will be over, I said, and this will become a day when something slightly out of the ordinary happened. That will happen soon.

But then I thought, Maybe that won’t happen. Maybe instead, Shannon—unaware of the cars or indifferent to the lack of motion—will lower the book and say one more time, Daniel, I see them. Maybe her hand, shaking from a vision she never expected, will find my fingers and push them into the warm yellow wheat. Or maybe the crows, restless from a hundred years of false movement, will finally break into flight.

Maybe the thin black birds— traveling swiftly, leaving empty spaces in the sky—will reach the low-hanging moon and settle there, wrap their wings around her hard white curves and talk about how the road below them, the one that is red and green, thrashes through the fields and doesn’t end anywhere.

Kevin Clouther teaches creative writing at Stony Brook University. His story collection, We Were Flying to Chicago, is out now from Black Balloon Publishing.