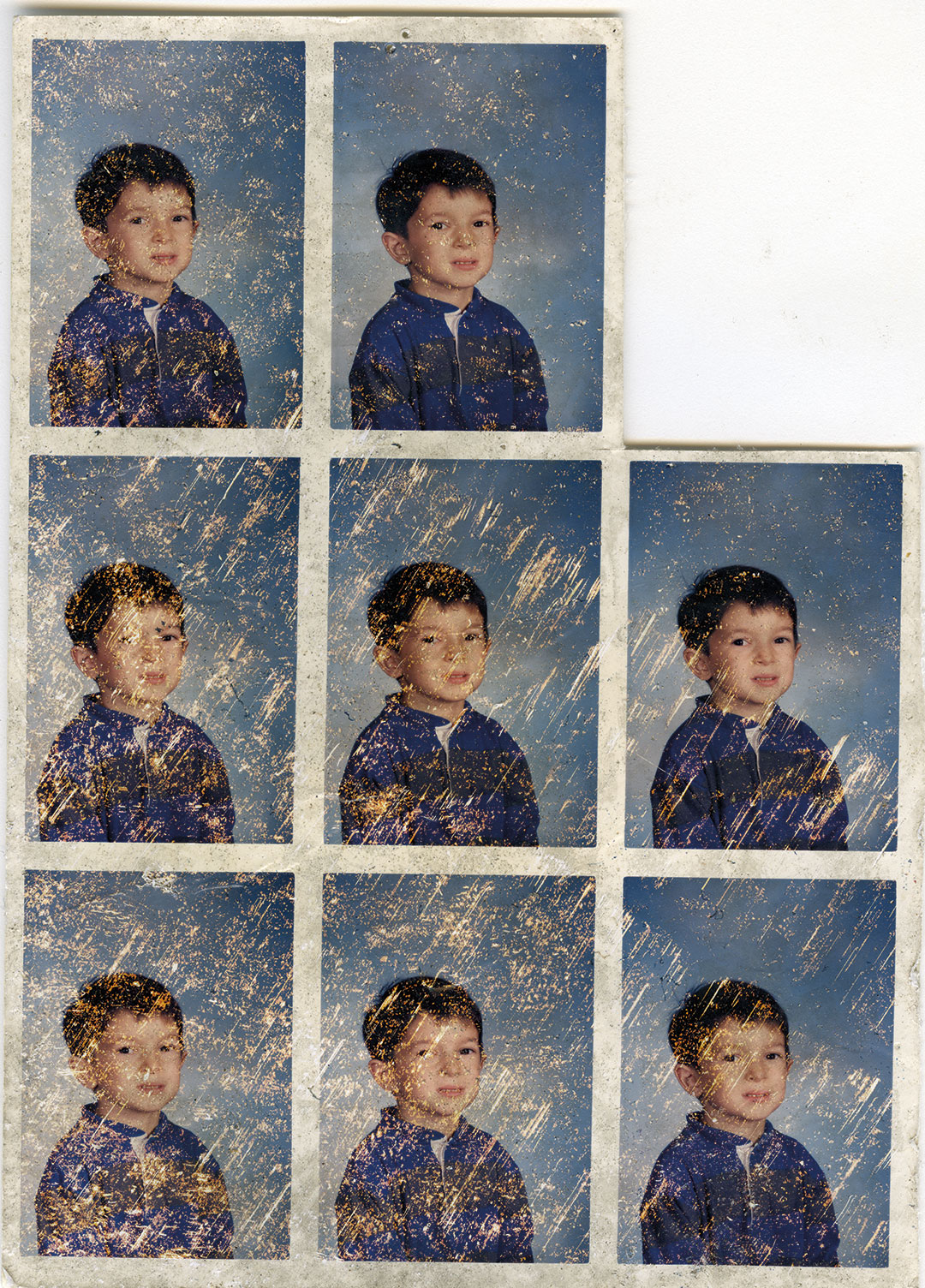

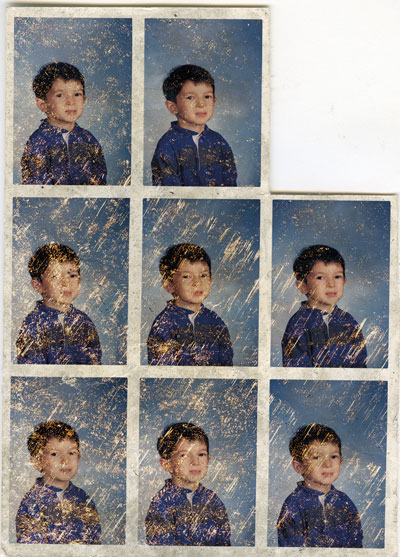

Every year there was a new version of this kid at school—the one who got singled out, the weakling, the faggot. It was like there was a defect in most kids’ genes that solicited cruelty. There was no escaping it.

At my school, Cobain was that kid. We rode the school bus together. His real name was Toby but he insisted that we call him Cobain. I don’t think he was even a Nirvana fan. Cobain was a mouth-breather with girly hips and thick glasses. Kids fucked with him mercilessly. Rednecks spit chewing tobacco at him, and jocks flicked his ears until they bled. Even the bottom feeders got theirs with cheap shots, like throwing batteries at the back of his head. Everyone got a piece.

Throughout the abuse, Cobain remained aloof and seemingly at ease. I envied that about him, but as an act of self-preservation, I never stood up for him. Instead, I made myself hate him for being weak. I imagined that if I became callous, the front would avert attention from myself. Sometimes it worked; sometimes there was no place to hide. Even then I knew to be grateful that, at worst, I was only invisible.

Cobain appeared to exist in some netherworld without parents and friends, without protection or even regard. He kept two belongings on him at all times: a pair of two-way radios and a frayed set of playing cards with naked girls on the back. He always had one radio clipped to his shorts and another pressed up against his ear. During the ride to school, he’d routinely lay out his playing cards, tit side up, tracing his finger over the breasts. I respected that he didn’t care if people knew he was a perv.

Throughout the torment, he’d busy himself adjusting the radio knobs and antennae until we arrived at school. I never knew what it was that he heard through the distorted frequencies, but he escaped us through the mysterious transmissions. It was his way of playing dead, a defense mechanism that earned him the nickname “Retard Radio.”

On an unusually quiet morning, there was nowhere else to sit on the bus. We crammed in, three to a seat, beside Cobain. I was close enough to smell his burped-up sugary cereal. I guess the rednecks were worn out, because for the first time I could register crackling intonations from the radio.

I was inside a Monte Carlo sitting beside Trick, a squirrelly nineteen-year-old white boy with gold teeth. That night he’d been driving us on an aimless search for a house party I wasn’t sure was happening. Trick had one of those haircuts that was long on the top, tied in a ponytail, and shaved underneath. After a severe car accident, his posture was offset due to a broken collarbone that fused crooked. Afterward, he got by on a pretty sweet settlement and an endless OxyContin prescription.

Trick and I were never tight. To me he was just the older kid with nothing better to do than hook up my friends with beer and drugs in exchange for house parties where the potential was high for baiting teenage girls into sucking his dick for key bumps.

Whenever Trick drank too much, I’d catch him staring at me. His voice would quiver when he’d tell me things like, “Goddamn, you sound just like Darrell. From the side you even look like he did back in the day.” And then he’d snap out of it, bleary eyed, apologizing to me with free blow that later provoked even more eerie sentiments followed by heated outbursts.

Darrell was his older brother, who died in the same car accident that had only scarred Trick with a slouch. I never met Darrell. All I’d seen of him were old framed photos Trick kept around his room. Darrell must’ve been in his mid-twenties when he died. From what I could tell, I guess we had similar deep-set blue eyes—but even that was a stretch. Whatever resemblance we had, I believed that was the only reason Trick was nice to me.

Trick always made me wonder if people like him were aware that life was getting just a little too sweet in the wrong way. Most older guys I knew who turned teenage girls into damaged goods didn’t last. I bet in the back of his mind Trick thought the same thing. I had a suspicion he secretly wished that he had died in that accident, not Darrell. I can’t blame him. At least Darrell had a decent haircut and fucked girls his own age.

That night we stopped at the 7-Eleven to buy booze. Stepping inside was like being sucked into a void of white noise. The fluorescents were too bright and the tinny speakers played “Footsteps in the Dark,” the song sampled in Ice Cube’s “It was a Good Day.” That disorienting melody was isolating.

Parked beside the front window, next to a Mountain Dew display, was an old man in a heavy, motorized wheelchair. His leathery face was sunken. There was a clear tube exiting his nose and another from his crotch, both leading into a backpack slung over the wheelchair’s handlebars.

Trick was outside pissing on the wall, clearly visible through the front window. Beyond him, I saw something gray and shapeless move across the parking lot. I squinted through the misty haze of street lamps. The diffused shape came into focus as it neared the store. Even though the figure was outside, still not entirely in sight, the gradual build of static could mean only one thing: Retard Radio.

It had been a few years since I last saw Cobain. He looked fatter and taller but still had the face of a damaged cherub. He was wearing a giant set of military headphones, connected to his coveted two-way radios. One was pointed up at a mess of electrical wires; the other was clipped on to his gym shorts, slightly tugging them down. There was something off-putting about his clumsy stagger, like he was overly medicated.

As Cobain approached the 7-Eleven, I saw Trick rush at him, cornering him back against the store’s window. I thought about running out to defuse the situation, but instead I stood there, riveted, and watched.

Cobain stood still out there, silent and trembling, and Trick threw his weight behind a sucker punch to the eye. Cobain never cried out. He just stumbled and slapped against the window. It sounded like moist meat thumping tile.

Outside, Trick was standing over Cobain, panting, clenching his fist in restraint. Cobain was flush against the ground, arms at his sides, his face was swollen but the bruising hadn’t started yet. I bent down to take a closer look.

I remember feeling a weird kind of ownership over his body, like we had just hunted down the last of an extremely rare and hideous animal, the kind that would later be stored in a jar of formaldehyde for exhibition at oddity museums.

Cobain stayed motionless. His mouth froze into a twisted circle that curled his lip in above his teeth. The skin around Cobain’s eye began to shift from a shiny opaque to baby blue. Because of his thick glasses it was hard to tell if he was faking hurt.

Trick picked up the dropped radio. He mockingly fumbled with the dials, then said, “Hey, faggot,” into it; his voice crackled tiny and robotic from the other radio still clipped to Cobain’s shorts—a move that made Trick laugh nervously. He tried covering it up with dumb jokes about pulling his shorts down to make sure he wasn’t playing dead.

I could see the worry manifest on Trick’s face. The times were catching up faster than I had hoped: Some modicum of morality had begun to set in. The good times were almost over.

Trick jammed the other radio into my chest like it was my turn to do something. I knew he only wanted to implicate me in the attack. Holding the walkie-talkie, I froze up, overwhelmed by the sound of radio static and buzzing lights fusing into an even drone. I thought of that quiet day on the school bus when I had sat beside Cobain. I remember him trying to cut through those knotted bands of static, and now I had his radio.

I could have asked Trick why he attacked Cobain, but what was the point. I already knew what he’d say.

“If you want to hang out in the barbershop, expect a haircut.” —Darrell, 1972-92

Christina and Lisa were sisters who sold coke, gel tabs, and random pills from their apartment. Their place shared a ventilation system with John Dee’s Tavern, which tarnished anything fabric or edible with the scent of barbecue sauce and coagulated pig/cow blood. After Lisa had a stillborn at a house party, they both disappeared. No one knew where to, but we assumed they went to live with their mother in Miami. Before I knew they left, we went to check on them. The door wasn’t locked, and a majority of their stuff was still in the apartment. Inside their bathroom I found an old photo of them in the medicine cabinet and a cow’s head in the bathtub. A week later John Dee’s Tavern extended their kitchen into what was once Christina and Lisa’s apartment.

I couldn’t sleep. At night I obsessed over what happened to Cobain at the 7-Eleven. I only dreamt of wandering through empty places—vacant outlet malls, warehouse units, the DMV, stationery stores, clinics, classrooms, Goodwill, luncheons, Pier One Imports, frozen food aisles. I only dreamed of places I didn’t want to be. No one was even chasing me. I was stuck, fucking off, begging for escape. Too often I woke up travel weary, stupid-eyed in the mirror.

Since the attack, Cobain hadn’t shown up at school. I thought of asking around, hoping one of my classmates had heard about his whereabouts, but no one even noticed he was gone. It occurred to me that on the off chance Cobain had been killed that night, or in the even more unlikely scenario that he’d been abducted by a third party, I didn’t want to bring attention to myself by asking questions.

Cobain hadn’t bled heavily, but Trick hit him full force. Afterward he wanted me to help drag Cobain’s body to the side of the store, away from the heavily lit parking lot. There was no way I was going to touch him. I didn’t even want to be there. Trick called me a fag and said he’d been wrong about me, I’d never be anything like Darrell. We never spoke to each other again.

I routinely checked the local missing persons reports but found nothing about Cobain. I even returned to the 7-Eleven, but there was nothing there, not even bloodstains.

Cobain had no friends. It was impossible to find out where he lived. Involving police was a stupid idea. If they didn’t lock me up as an accomplice, Trick would hunt me down. Either way I was fucked, so I waited it out.

I kept Cobain’s radio in my room buried beneath a growing pile of laundry. I thought it would bring bad luck to have it in plain sight. I could totally see some Hellraiser-type shit happening, like it opening up and ripping me out of existence.

Worse than my guilt and fear was the relief I felt. I told myself that his evaporation was a small death that had brought him to a better place.

I might have been turning into a monster. I went through the motions.

More than usual, I kept to myself.

I was grounded, alone in my room on a Friday night. Earlier in the week, I bought myself three hits of acid. I’d been saving them in anticipation of the looming weekend of silence and solitude. Silent because my parents, as a tactical addition to my growing list of punishments, had decided to confiscate my CD player. They hated that I only listened to death metal. My mother said it gave her anxiety. My father was confused, disappointed.

That night after my parents fell asleep, I switched out the iridescent light bulbs in my room for red ones, took all three hits of acid, pulled Cobain’s radio out from under the dirty clothes, and for the first time turned it on. As it hissed then crackled to life, I was immediately brought back to that day on the bus. I could even smell the burped-up cereal.

I kept the acid inside my mouth until the tabs turned into a pulp. I sucked in as much saliva as possible to swallow them down with. I knew it didn’t make any difference if I digested them, but I wanted that night to be intense. It was the first time I had ever done acid alone. The effects kicked in quickly; within fifteen minutes my walls were breathing vascular flaps. The floaters gliding over my eyes looked like fat crustaceans. I became overly intrigued with the idea that beneath my floor were narrow rivers of shit flowing through sewage pipes that connected my home to other homes and back. Clearly, I was tripping balls.

All night I lay there motionless, clenching his radio to my chest, feeling the sound vibrations tunneling into my lungs. I was sifting through currents of distortion, waiting for that one signal, word, breath, cough, anything that would prove Cobain was still out there, alive.

Instead, I heard more rolling waves of static occasionally punctuated by pirate radio signals of Latin music, muffled trucker jargon, jerk-off talk, church organs absorbing the pious ramblings of low-budget evangelicals. This clusterfuck of noise was Cobain’s safe place. This was where he went to escape us.

Paul Kwiatkowski is a New York-based writer and photographer. His work has appeared in numerous outlets, including Juxtapoz, Beautiful Decay, American Suburb X, and LPV Magazine. Kwiatkowski was born in Jersey City, NJ and grew up in South Florida during the 1990s. He studied at Tufts University and The Museum School of Fine Arts in Boston, as well as at F + F School for Art in Zurich, Switzerland. Visit paulkmedia.com and follow Paul on Twitter @XOPK.

More About And Every Day was Overcast

Out of South Florida's lush and decaying suburban landscape blooms the delinquent magic and chaotic adolescence of And Every Day was Overcast.

Paul Kwiatkowski's arresting photographs amplify a novel of profound vision and vulnerability. Drugs, teenage cruelty, wonder, and the screen-flickering worlds of Predator and Married…with Children shape and warp the narrator's developing sense of self as he navigates adventures and misadventures, from an ill-fated LSD trip on an island of castaway rabbits to the devastating specter of HIV and AIDS.

This alchemy of photography and fiction gracefully illuminates the travesties and triumphs of the narrator's quest to forge emotional connections and fulfill his brutal longings for love.