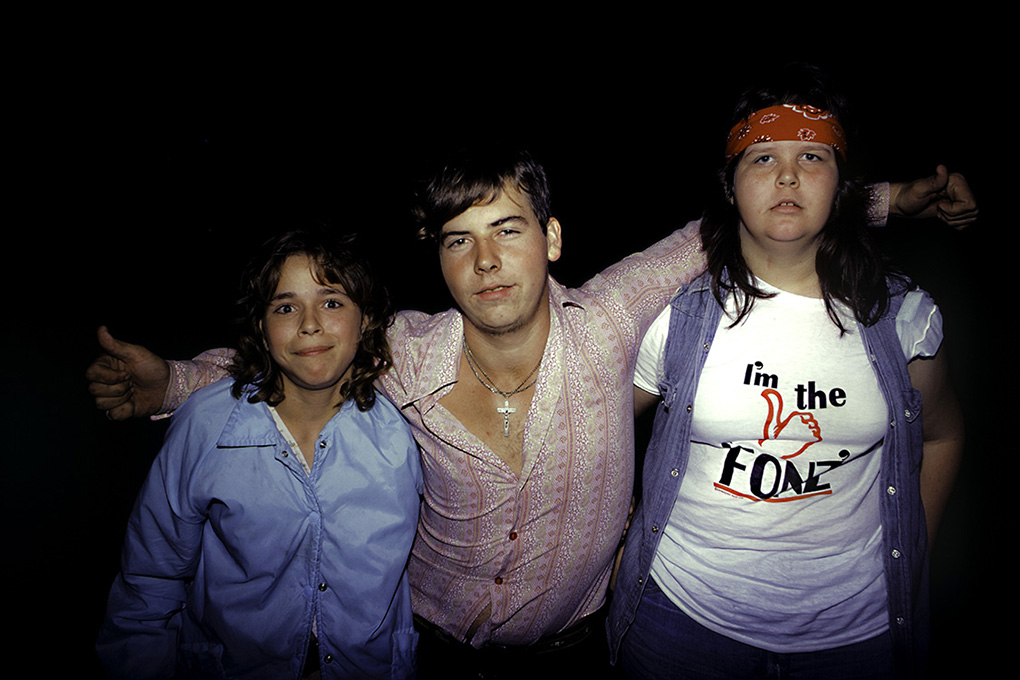

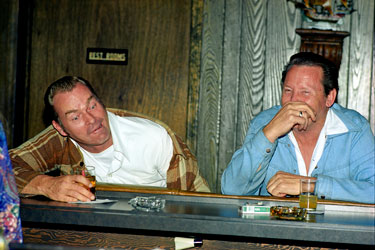

Photographer Scot Sothern’s debut memoir Curb Service captures the pathos of an aspiring provocateur adrift in contemporary America. Beginning in the 1980s, the book recounts Scot’s initial drive to photograph prostitutes and his path to single fatherhood on the skids. The interactions between the photographer and his subjects are the device through which solace and introspection flow. Along the road, there are intermittent flashbacks to Scot's adolescence in rural Missouri during the late ‘60s and ‘70s.

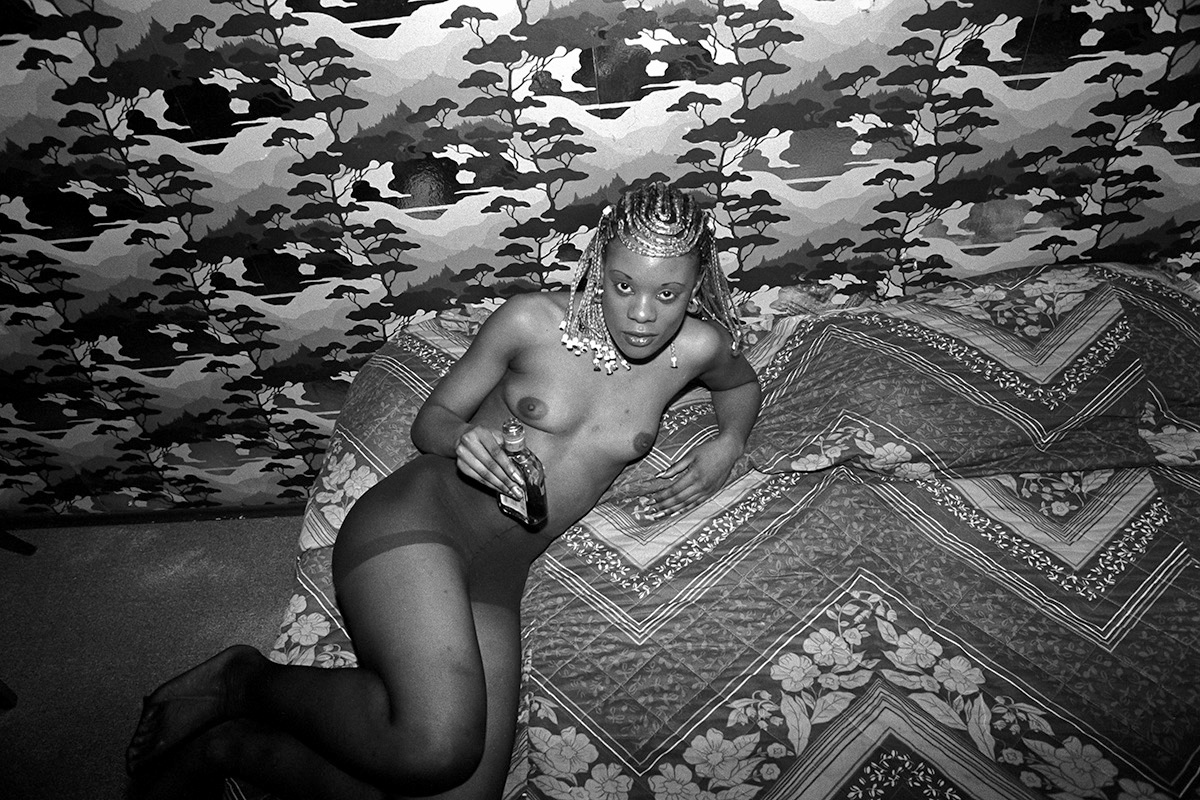

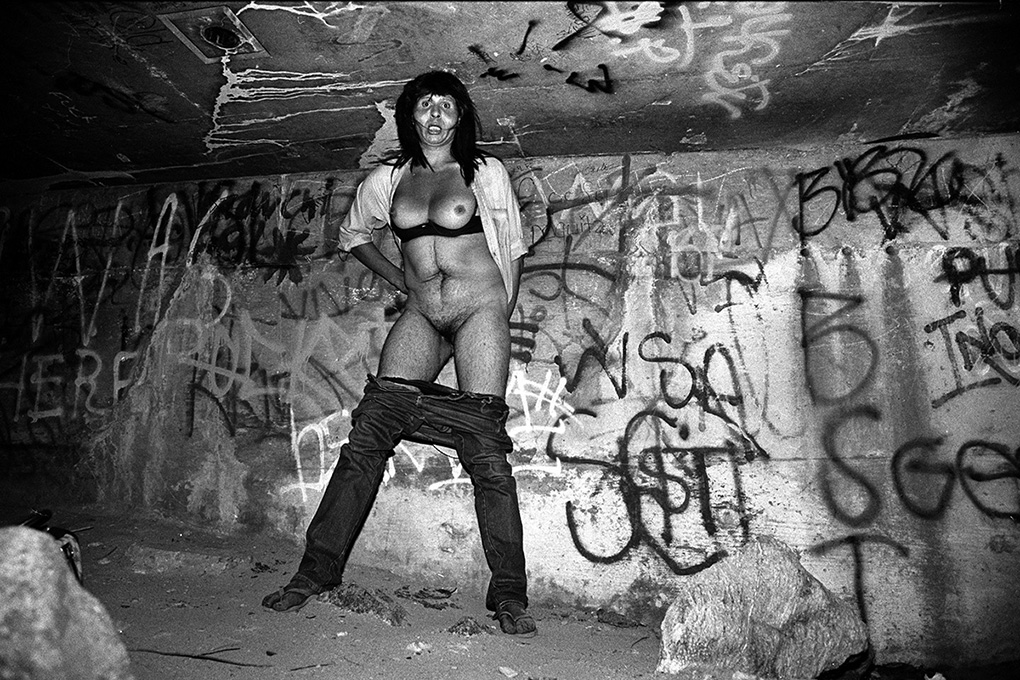

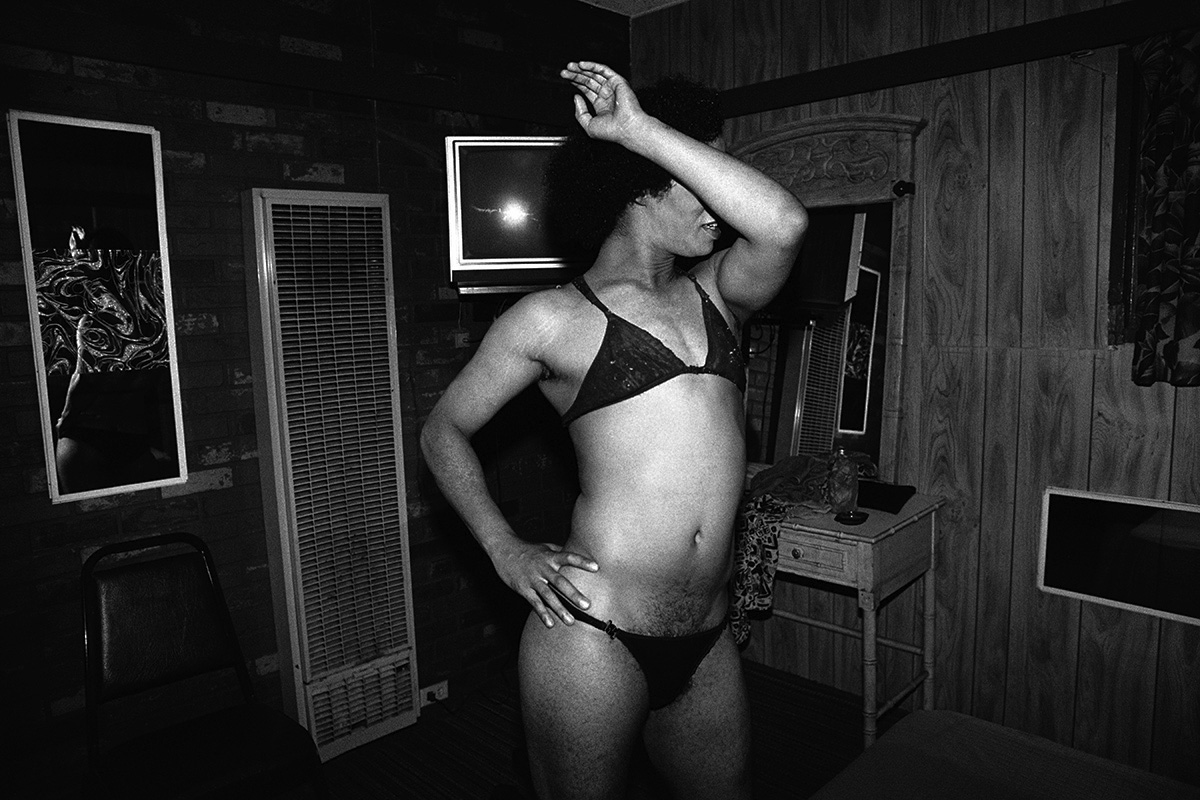

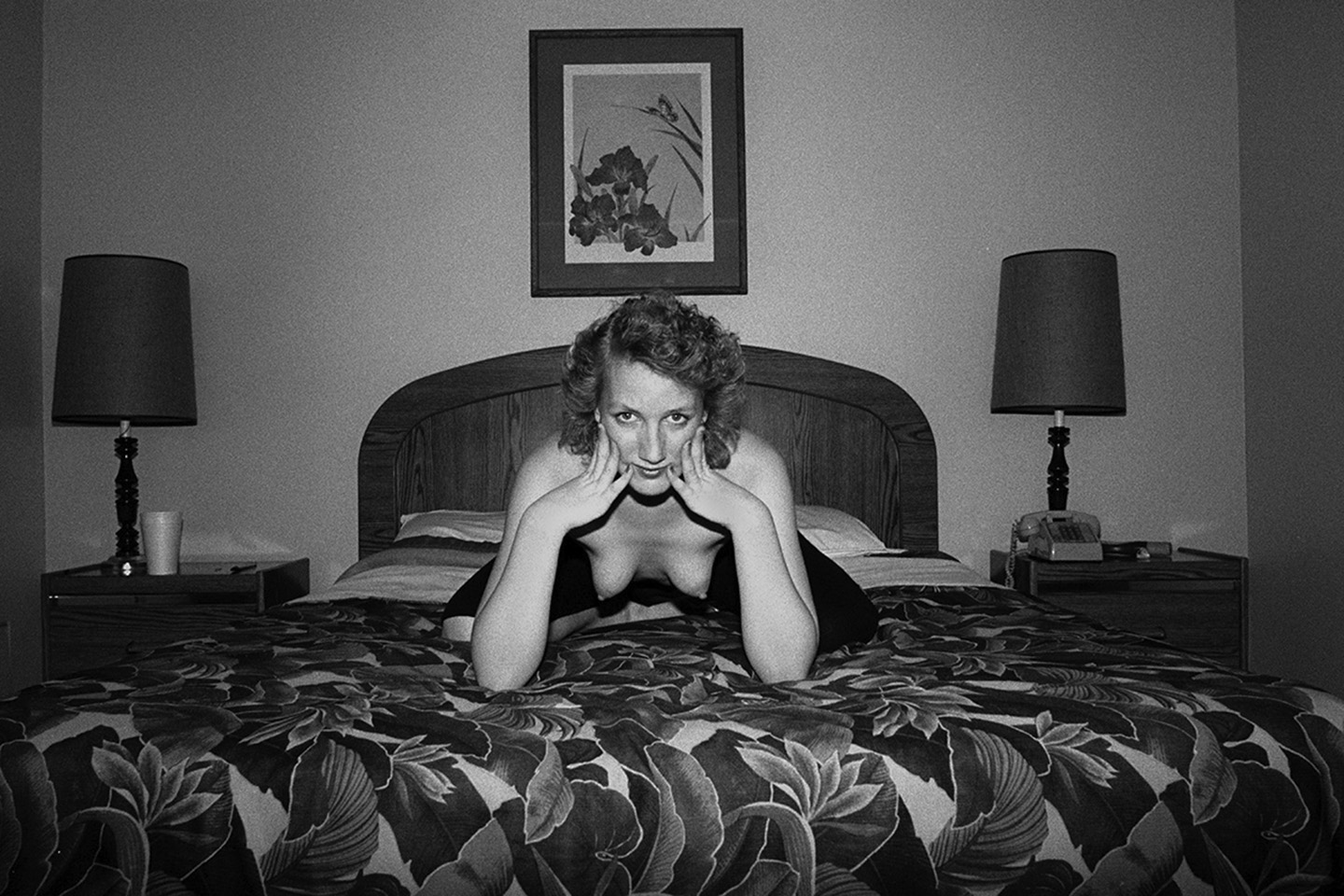

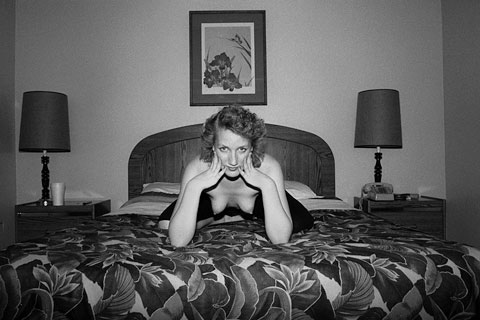

Scot’s photography had largely gone unnoticed until the release of his first body of work, Lowlife, an elegant black-and-white photo collection of horny tension with the base level of the sex-for-cash pyramid. This was followed by New Low, an upcoming exhibit of recent color photographs documenting Sothern’s return to form after an almost 20-year hiatus due to financial anxieties and a debilitating motorcycle accident.

In Curb Service, there’s no hooker with a heart of gold. Scot’s work remains a testimony to the battering that American life can be, while simultaneously leveling the playing field between viewer, subject and photographer. By combining fluid text with sordid behind-closed-door images, Scot’s vision has merged into a perilous sweet spot: an eviscerating self-examination in which readers are allowed to ride shotgun down his unique journey to recognition as an original voice in contemporary American art.

After 30 plus years of virtual obscurity, Scot’s body of work now stands firmly at the intersection of fine art, documentation, narrative and authenticity. His point of view brings us right up to the precipice without concession. In Curb Service, there’s no moral higher ground to look down from.

"His lyricism and imagery fill my head with the scent of a Camaro’s leather upholstery baked in the California sun and pussy."

Scot’s compelling vision is one of few in contemporary art that continues to give me a jolt with every viewing. His lyricism and imagery fill my head with the scent of a Camaro’s leather upholstery baked in the California sun and pussy. During a conversation I recently had with Scot and Bryan Formhals of LPV Magazine, Scot offered up one of the most bona-fide words of advice an ambitious young man could heed: “Follow your hard-on.”

"I discovered that you can take a picture of someone and bring something out in them that shows who they really are."

How’d you start?

I started out as a portrait photographer — not a groovy portrait photographer. My father was a portrait photographer, so I grew up in the studio. His idea of a good portrait was a flattering likeness. I think that for someone trying to make a living at it, that’s a good way to think.

He used to photograph weddings, sometimes two a week. Whenever he had to take a picture of the bride, he looked at her through the eyes of the groom because on that day she’s the most beautiful woman on Earth. What happened with me after doing portrait photographs that way was that one day I discovered that you can take a picture of someone and bring something out in them that shows who they really are.

Portraiture is such a beast. It’s those micro-expressions or the way they move their arm at the last second — something along those lines. For me, it’s so damn difficult to know if this is a good portrait or a miss. Do you think portraits are truth, your fiction or somewhere in between?

I think it’s somewhere in between. It’s my idea of what it is. The pictures of prostitutes, the old ones and the news ones, they’re as much a portrait of me and of the person.

"At some point, the picture became more important than the boner."

What is it about shooting prostitutes?

Initially, I was following a hard-on. That’s really a lot of what it was about. I came to the conclusion at some point that as long as I’m going to be doing this, I should be taking pictures. At some point, the picture became more important than the boner. Nowadays it’s only about the pictures. The boner is still there, but it’s much more selective. When you’re in your 30s, you get a hard-on reading the funny pages.

"When I think back to the best pictures I’d taken in my life, those are the ones where I had a hard-on."

I always thought of photography as a primal thing, like an instant connection with reality, which is tied with sexual desire. Did you ever see the wires crossing there in your head where the two became one in the same?

Even with portrait photography, you’re trying to get something out of a person. When I think back to the best pictures I’d taken in my life, those are the ones where I had a hard-on.

"I’m out there at 3 in the morning taking pictures. That’s noir."

After having read your book, I think you’ve captured in your photos — which I’m not sure is totally obvious without the text — a really empathetic moment between you and these girls, but it’s woven into the narrative with your personal story and family life. I think the two really bleed into each other in a great way: You’ve found a way to elevate both the images and the text. For a memoir, you’ve built a lot of suspense that seems to borrow from L.A.-style noir. Can you tell me a little about the process of writing this?

When I write, I don’t think of it as being noir-ish at all, but when I read it, I do. Sometimes when I go back and read things I wrote 20 years ago when I was teaching myself to write, I think to myself, “Jesus, am I reading Raymond Chandler?” — even though he is not someone I would put on my list of influences. I think the noir-ish element comes from the kinds of pictures I do. I’m out there at 3 in the morning taking pictures. That’s noir.

Has your approach to taking these photographs changed over the years?

No. I started doing it again last year for the first time in 20 years. In 1990, I went through many changes and I had some physical problems. I had retired from photography and figured I’d be a writer. If I couldn’t make a living at one thing, I should try something else. I started teaching myself how to write. I occasionally took out the camera, but I no longer went out to take pictures. But now, when I go out to take pictures, it’s like riding a bike. I did it exactly the way I did it before: I go out with a single flash on the camera; I pick out the subject and a place to go, or I don’t find a place to go and do it right there. I’m in and out in five minutes.

I came of age when HIV and AIDS were really prevalent on the news. It was a huge influence on my understanding of sexuality. Did that inform your work or the way the girls reacted to you?

The way I reacted to them was very different. I grew up during the sexual revolution. I grew up during all the revolutions. We were fuck crazy. When I was young and used a rubber, I used it as a guard against pregnancy. Disease wasn’t something we even thought about. By the time you guys came of age, it became about disease, life or death. I was photographing throughout the late ‘70s and ‘80s. It was a very sad time, and some of my friends are not around because of it. I carried condoms in a backpack, handing them out like Johnny Appleseed in the ‘80s. In spite of all the things I did during that time, I never once put myself in danger of disease. I was maybe a little crazy, but I wasn’t suicidal.

How do you feel about prostitutes no longer being streetwalkers but existing online. Would you ever consider courting them that way?

I don’t want to get to know anybody.

Paul Kwiatkowski is a New York-based writer and photographer. His debut novel, And Every Day was Overcast, will be out in October from Black Balloon Publishing. His work has appeared in numerous outlets, including Juxtapoz, Beautiful Decay, American Suburb X and LPV Magazine. Visit paulkmedia.com and follow Paul on Twitter @XOPK.