How the Back Room Shakespeare Project Gave Up on Theatre—and Revived It

Young people don't go to the theater. Broadway League data reveals that in 2011 the average age of a non-musical theater-goer was 53. More convincing than hard numbers, if you are younger than 30, ask your friends if they want to see a play. They will act like wild horses that think they are being tricked into a barn. "How long is it?" they whinny skittishly. "How much will it cost?" as they take little steps backward.

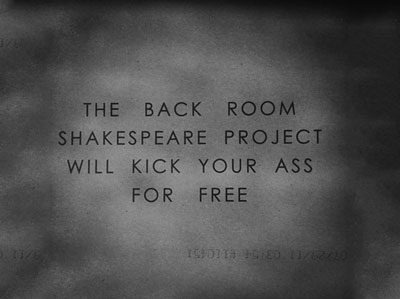

I did not want to go the first time someone suggested I see Chicago's Back Room Shakespeare Project. Founded in 2011, this collective of actors rehearses a play once, without a director, and performs it at a bar for free. I had visions of being trapped, bored, talked at. I caved in February of this year, and underwent the inaugural weirdness of seeing two hundred people, mostly under 30, electric with anticipation for Chekhov's Three Sisters (it was an experimental departure from Shakespeare.) To be clear: this wasn't abridged musical Three Sisters or improvised Three Sisters or drinking-game, diaper-wearing trivia night Three Sisters. The whole play, memorized and spouted by real actors.

"No board, no strategic plan, no subscribers, no overhead, no endowment, no production costs... How to do you stay mobile, subcultural, leaderless, and altruistic when success is telling you to become a theater company?"

I wasn't bored. I stood for about three hours, sometimes inches away from the would-be Muscovites who loudly hurled their lines over the rain pelting the skylight. Sometimes I was embarrassed not to have the anonymity of a seat in a darkened theater. In this sense Back Room can recall experiences of performance art where comfy spectating becomes suddenly uncomfortable—strolling through a museum until the object encountered is not a painting but Tilda Swinton catching Z's in a terrarium. Then you feel like a creep. In Three Sisters, two actors who didn't know each other and had only rehearsed once kissed about thirteen inches from my face. He lifted her in the air. I stood behind them as they made out, aware I was part of the spectacle, like the unkissed friend at the dance, sucking on a Diet Coke and being all "No big deal."

At the meeting held a few weeks after Three Sisters to discuss how the performance went (they call it a "debrief"—it's announced on Facebook and open to the public) people rhapsodized about immediacy and participation: "I felt I was helping to build the momentum of the Chekhov," said a viewer. For me, participation was potentially awkward, but this kept me riveted. When will someone erupt and will it capsize this family drama? At Three Sisters, someone began clapping suddenly in agreement with one of the characters. Two solitary claps in, he realized no one was going to join him, and squeaked "sorry," which got a laugh. I saw Back Room perform Shakespeare's The Two Gentlemen of Verona a few weeks after Chekhov and realized in contrast how porous Shakespeare is to audience participation. Proteus's betrayal in that play is built to cue Springer-esque booing: "I love Julia," he says, waits a beat, and then, the betrayal measured in a perfect grammatical ticking of the second hand in the wrong direction: "I did love Julia." It was an invitation to voice our anger.

Co-founder, actor, and youngish person (30!) Samuel Taylor doesn't care if you feel awkward, or if someone gets kissed too close for comfort; it's all a step up from the disconnect of contemporary theater, where "The actors are blinded by the stage lights, barely able to see the audience sitting quietly in the darkness, turning their tickets into fifty-dollar naps." (There's more manifesto where that came from.) The problem with theater for younger generations might have to do with cost ($20 for a student ticket?) and content (Ibsen say what now?). But Taylor and co-founder Kelley Ristow, also a young actor (28) had it in for the very structure of the actor-audience relationship. "We live our whole lives with an audience," said Taylor. "The idea of denying an audience is more loony now than to any other generation."

It is no accident that Shakespeare, of all the dusty, corseted old-timey theater out there, should be the fuel inside this rocketing project. Shakespeare wrote for theater performed as Back Room performs it. There might be one rehearsal, usually in the morning, to get down basic entrances and exits. Per Shakespeare scholar David Bevington: "No director oversaw [actors'] work or had the luxury of weeks of preparation. Directorial ‘concept' was...entirely impractical." Kenneth Branagh, not to say all of filmed Shakespeare, is the opposite of Shakespearean.

Back Room's performances come off as a loud adventure, not a scholarly laboratory. When the crowds come barreling through the doors and fight for standing room in big, Chicago bars like Frontier or the Mystic Celt, they aren't hollering the phrase "historicist Shakespeare" through their wet, curling lips. But when actors perform with nothing more than the the language to go on, and without having nailed it pat in weeks of rehearsals, they actually have to communicate the play line by line, choice by choice, almost like improvisers. So, in Two Gentlemen, when two servants are bickering and one says, "Why dost thou stop my mouth?" and the other replies "In thy tale," and the first repeats, with campy flourish and an arched brow, "In thy tail!" The delivery of the language as the Bard wrote it, even after only one rehearsal, makes it clear that this is a filth-suffused pun. As the guy sitting next to me gasped, "Oh my God, that's a rimjob joke." Historicism at work.

The jokes go off like firecrackers, the plot moves, because Taylor and Ristow are militantly against "Shakespeare voice," otherwise known as "Good Speech" or Standard American English, a contrived dialect that's been deployed at major theater houses since the middle of the 20th century. (To hear the difference between SAE and normal speech applied to Shakespeare, click here.)

"Acting: not starving, not auditioning, not punching out paparazzi. Shakespeare makes acting the principle metaphor for behavior, and thousands of miles from Broadway or Hollywood, this essence manifests magnificently."

Shakespeare lived among and wrote for actors, and the writer points to their work as they carry out his. In Two Gentlemen, Julia has been thrown over by her lover for Sylvia; she holds the picture of Sylvia and compares herself:

Here is her picture: let me see; I think,

If I had such a tire, this face of mine

Were full as lovely as is this of hers:

And yet the painter flatter'd her a little,

Unless I flatter with myself too much.

In the Back Room production in March, the actress playing Julia, Jaclyn Hennell, whipped out a headshot, and seemed to be asking, Why didn't I get the role? Watching, I didn't think that this was some inside joke for other actors. It's a play in which a stark betrayal is explored and eventually repaired through role-playing and disguise on the part of the one betrayed. I understand why so many actors attend Back Room performances, but in putting themselves in charge, they've ignited something real and explicit in Shakespeare that non-actor audiences see. Shakespeare thematizes disguises, actors, role-playing, plays within plays— Hamlet famously delivers tips on acting technique to the traveling players ("O, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters...") Acting: not starving, not auditioning, not punching out paparazzi. Shakespeare makes acting the principle metaphor for behavior, and thousands of miles from Broadway or Hollywood, this essence manifests magnificently.

I got interested in the lives of Chicago actors, curious about why they threw themselves at this unpaid one-night performance sometimes requiring weeks of memorization. What is this surplus energy that Back Room feeds on? Katy Collins is a Back Room player, small and blond and 28 years old, the age to be cast as the ingenue. But, she told me, "Those weren't the roles that were interesting to me. I'm not a lover in my life. I don't connect with the young girl being so in love. And for a while that was all I could be cast as." Another actress told me she's waiting to age—she thinks she'll hit her stride as cast-able in her forties. In Three Sisters, Collins leapt to play the bumptious, crass Natasha. Back Room's volunteer self-casting lets the actors toy with the gap—a career-long gap based on things outside the actors' control like age and race—between what they like to play and what a casting director sees. Alex Weisman, short, plucky, blond and effusive, has had a lot of early success in his theater career (he's 25, but already as a junior at Northwestern picked up a Jeff award, Chicago's Tonys, for Supporting Actor in History Boys.) Even in such ideal circumstances, for him Back Room means getting to play who he thinks he is: "Everyone sees me as a comedian because I'm short and I'm pale and I'm loud. So my skill set is, be funny and abrasive. But what I love to do is to be really subtle." He played Laertes in the Back Room Hamlet with simmering anger, unshackled from "sexuality as a punchline."

"Chicago is a place you will always find work, but you won't get paid."

I interviewed many of the Back Room performers about the Chicago acting community and I can't quote any of them, because their gushing sincerity would read like an advertisement for a wellness center in the Berkshires: "This is a place you can really grow"; "everybody here supports each other." It's a small community—according to the Actors Equity Association, there are 1,475 registered Equity actors in Chicago and over 16,000 in New York (not all actors are Equity, but the ratio is still telling.) There are around ten times more actors in New York and four times as many theaters, so theoretically there should be more opportunity in Chicago. Hence what I heard repeated from Back Room actors: Chicago is a place you will always find work, but you won't get paid.

Unlike at a wellness center in the Berkshires, nobody's rich. Average pay for a principal at one of the big theaters like Steppenwolf or the Goodman—and very few people get these roles—is about $800/week. So if you are always working at the top of your game all year round in Chicago you top out at just over $40,000, and that's if you are playing the plummest role 52 weeks of the year. On the side they're administrators, many teach theater or work with educational theater programs, there's a commercial hand model, a chocolatier, nannies, a busker at the Lincoln Park Zoo, a "nylon cutter at an ultimate frisbee jersey factory."

"The problem is, there's more theater in Chicago than there is audience for it," said one actor. Chicago has over 200 small theater companies. A hint at how diverse they are: Akvavit is dedicated only to contemporary plays coming out of Scandinavia. I went to one of their plays this past July, and found myself among four audience-members in a 50-seat theater, facing a brave cast of a dozen (so, so brave: The play, bleak but I loved it, was about a group of dysfunctional Finnish drunks, and several of them were nude most of the time, their genitals hanging genially, like hounds' tongues.) This is why Ristow and Taylor want to preserve theater by abandoning the company model: no board, no strategic plan, no subscribers, no overhead, no endowment, no production costs. Performances are announced a few weeks ahead online. "Outreach" is Facebook and word of mouth.

In refusing to be a theater company, Back Room has shaken off the shabby non-profit pall that so many companies wear, an insidious assumption that theater has to beg for audiences. This assumption, as several Back Room actors explained, can depress a show. For six years, Matt Holzfiend worked in box offices at two of Chicago's big theaters, Looking Glass and the Blue Man Group, and described how in the subscriber model of the big theaters, "Subscribers are put on a pedestal and told, ‘We exist because of you, we need you.' What happens is, unfortunately it perpetuates this idea that theater is a charity. It works on, ‘thank you so much with gracing us with your presence, we know you'd rather go see a movie.' That trickles down into the actors and the artists."

No one makes a profit from Back Room, but no one has to beg, and when the actors please themselves first, there's plenty left over. As success has flooded the group, it's harder to behave in a "twittery, food-trucky" way (as Ristow put it, since they announce themselves online and pop up in bars.) At a recent debrief, Ristow asked: "How do we feel about issuing tickets?" A table full of performers stuck out their thumbs and tipped them straight south. But the overcrowding has to be dealt with. Should they begin to charge? Should they do performances twice? Should they give IOU's to those turned away? How to do you stay mobile, subcultural, leaderless, and altruistic when success is telling you to become a theater company? A minority of the actors hinted that "this is how Chicago Shakespeare began," or Second City, institutions with multi-million dollar operating budgets that started in bars decades ago. Ristow and Taylor would balk at the idea of Back Room morphing into an institution. For them, continuing to subvert the norms of traditional theater is the only way to remain vital.

On the night of Three Sisters, Kelley Ristow played Masha, a stormy woman who pouts, cries and kisses in the course of the five-act play. When the play was over, Ristow had been pacing and staring and pleading for three hours, the net of the audience pulled tight around her throughout. There was no curtain to drop after the last line of the play, so she stood there, no longer Masha, not quite Kelley, completely visible in a state that is usually hidden. She looked like she had post-traumatic stress disorder. She was in some kind of survival mode, smiling but not listening, holding her ribs, maybe to bring her breathing to normal. One of the actors told me that the physical stress actors undergo opening night is equivalent to a car accident. Every Back Room performance is an opening night, with the added bonus of the audience being as excited as the actors.

Image credits, from top: Flickr user brandonschauer, John Tyler Core (3), Chad Bay, John Tyler Core (2), Samuel Taylor.

In the final installment of Building Hamlet, set designer Meredith B. Ries offers her final reflections on what she considers "[an] experiment with blending humor and tragedy, evil and humanity... a dark jibe at religious faith, at royalty, at ambition. [Hamlet is] a ghost story and a love story."

When I volunteered last year at Chicago's Smart Museum for a gallery show made out of margarine by German artist Sonia Alhäuser, I discovered that the food art trend is transforming museums from the inside out—their layout and organization, their staff and management—as, more and more, they find themselves literally catering to food as a medium.